Al-Salihiyya

الصالحية Salihiya[1] | |

|---|---|

Al-Salihiyya c. 1936. Woman weaving papyrus mat. | |

| Etymology: This name is elsewhere attached to buildings or establishments founded by Salah ad-Din (Saladin).[2] | |

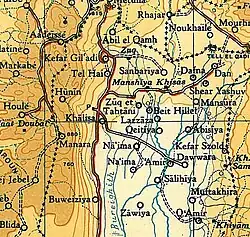

.jpg.webp) 1870s map 1870s map .jpg.webp) 1940s map 1940s map.jpg.webp) modern map modern map .jpg.webp) 1940s with modern overlay map 1940s with modern overlay mapA series of historical maps of the area around Al-Salihiyya (click the buttons) | |

Al-Salihiyya Location within Mandatory Palestine | |

| Coordinates: 33°10′02″N 35°36′45″E / 33.16722°N 35.61250°E | |

| Palestine grid | 207/285 |

| Geopolitical entity | Mandatory Palestine |

| Subdistrict | Safad |

| Date of depopulation | May 25, 1948[1] |

| Population (1945) | |

| • Total | 1,520[3][4] |

| Cause(s) of depopulation | Fear of being caught up in the fighting |

| Secondary cause | Whispering campaign |

Al-Salihiyya (Arabic: الصالحية) was a Palestinian Arab village populated by people traditionally associated with the Ghawarna, a generic exonym denoting inhabitants of the drainage plains of the Hula Valley.[5] It was depopulated during the 1948 War on May 25, 1948, by the Israeli Palmach. It was located in the Safad Subdistrict, 25 km northeast of Safad, at the intersection of the Jordan River and Wadi Tur'an.

History

Canoeing pioneer John MacGregor was taken prisoner by the villagers of Al-Salihiyya during his exploration of the region in January 1869.[6] During his second night in the village he ate with the village sheikh and 50 other men. The meal consisted of "kusskoosoo" which MacGregor described as "a kind of small bean porridge uncommonly good to eat" and was eaten with saucers of buffalo cream. It was served on a communal wooden plate with wooden spoons for the cream. "They all behaved with excellent propriety and good breeding, but without constraint."[7]

In 1881, during the late Ottoman period, the PEF's Survey of Western Palestine described the village as "a mud village, containing about ninety Moslems; situated on plain of arable land, with march and river near."[8]

British Mandate era

At the time of the British Mandate for Palestine, the village had a population of 1281, all Muslim except 2 Christians. They occupied a total of 257 houses, according to the 1931 census of Palestine.[9]

A visitor to the village in 1936 noted that the inhabitants, along with those in other Huleh villages, had a "pronounced negroid element" and suggested they may have originated from Sudan or from slaves purchased in Mecca and resold at Ma'an. Their dialect was close to Egyptian Arabic. The village's main industry was harvesting the papyrus groves of Lake Huleh and the manufacture of papyrus matting. The mats were either fine work for interior use or courser work for building construction. The reed huts were made weatherproof in winter by adding further layers. A roof might end up eight or nine mats thick with the walls made up of four or five layers. They kept chickens, geese and buffaloes. The arable land was made difficult to plough by an invasive low growing grass similar to couch grass, called Injeel or Najeel. Some wheat, Indian corn and millet (dura) was being grown. The villagers also caught fish, of which there was an abundance, with drag nets as well as cast nets. They also acted as guides during the duck shooting season. The writer expressed fear for their future. "The whole area has been taken over by Jewish colonists who intend in the near future to drain it and convert it into useful arable land."[10]

In the 1945 statistics the population was 1,520, all Muslims,[4] owning 4,528 dunams, while Jews owned 789 dunams, and 290 was publicly owned, according to an official land and population survey.[3] Of this, 23 dunams were allocated for plantations and irrigable land, 4,230 for cereals,[11] while 94 dunams were classified as built-up areas.[12] The village had a mosque and an elementary school for boys.[13]

1948, aftermath

According to Israeli sources, the village had traditionally been ‘friendly’ towards the Yishuv.[14] In late May, 1948, the Haganah reported an argument in Salihiya between youngsters and village elders. The youngsters thought it best ‘to approach the Jews and hand over their arms and stay’. The elders, however, feared that if an Arab army nonetheless reached their area, they would be deemed traitors, ‘and the village would be destroyed.[15] According to Haganah sources: ‘They wanted negotiations [with us]. We did not show up. [They became] afraid.’[14] The village was depopulated on May 25, 1948,[1] by the Palmach's First Battalion during Operation Yiftach.[13]

Walid Khalidi described the village remains in 1992: "The village has been obliterated; no trace of it remains. Residents of the settlement of Kefar Blum cultivate the surrounding land."[13]

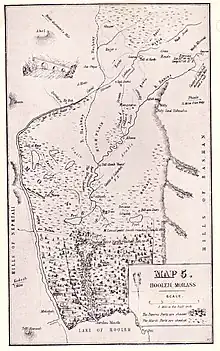

Al-Salihiyya (Salhyeh) marked on John MacGregor's map. January 1869

Al-Salihiyya (Salhyeh) marked on John MacGregor's map. January 1869 Example of a papyrus reed house in the Hula valley. c. 1910.

Example of a papyrus reed house in the Hula valley. c. 1910. Hula Bedouin 1935

Hula Bedouin 1935 Al-Salihiyya, 1944 (bottom right quadrant).

Al-Salihiyya, 1944 (bottom right quadrant). Preparing papyrus for weaving.

Preparing papyrus for weaving. Members of the Yiftach Brigade in the Hula with an example of local matting. 1948

Members of the Yiftach Brigade in the Hula with an example of local matting. 1948

See also

References

- 1 2 3 Morris, 2004, p. xvi, village #15. Also gives causes of depopulation.

- ↑ Palmer, 1881, p. 93

- 1 2 Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 71 Archived 2011-06-04 at the Wayback Machine

- 1 2 Department of Statistics, 1945, p. 11

- ↑ Sliman Khawalde, Dan Rabinowitz, 'Race from the Bottom of the Tribe That Never Was: Segmentary Narratives Amongst the Ghawarna of Galilee.' Journal of Anthropological Research Vol. 58, No. 2 (Summer, 2002), pp.225-243

- ↑ MacGregor, 1869/1904, pp. 223-246. Nb going rate for holding an English man for ransom was at least 100ll.

- ↑ MacGregor, 1869/1904, pp. 238-239

- ↑ Conder and Kitchener, 1881, p. 203

- ↑ Mills, 1932, p. 110

- ↑ Palestine Exploration Fund Quarterly Statement. October 1936. pp. 225−229. "A Visit to the Mat Makers of Huleh" by Theodore Larsson.

- ↑ Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 121 Archived 2018-09-26 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 171 Archived 2018-09-26 at the Wayback Machine

- 1 2 3 Khalidi, 1992, pp. 492-3

- 1 2 Morris, 2004, p. 251, note #708, p.303

- ↑ Morris, 2004, p. 96, note #171, p. 146

Bibliography

- Conder, C.R.; Kitchener, H.H. (1881). The Survey of Western Palestine: Memoirs of the Topography, Orography, Hydrography, and Archaeology. Vol. 1. London: Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Department of Statistics (1945). Village Statistics, April, 1945. Government of Palestine.

- Hadawi, S. (1970). Village Statistics of 1945: A Classification of Land and Area ownership in Palestine. Palestine Liberation Organization Research Center. Archived from the original on 2018-12-08. Retrieved 2009-08-18.

- Khalidi, W. (1992). All That Remains: The Palestinian Villages Occupied and Depopulated by Israel in 1948. Washington D.C.: Institute for Palestine Studies. ISBN 0-88728-224-5.

- MacGregor, J. (1869). The Rob Roy on The Jordan. A Canoe Cruise in Palestine, Egypt, and the Wates of Damascus (8th, 1904 ed.). John Murray.

- Mills, E., ed. (1932). Census of Palestine 1931. Population of Villages, Towns and Administrative Areas. Jerusalem: Government of Palestine.

- Morris, B. (2004). The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem Revisited. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-00967-6.

- Palmer, E.H. (1881). The Survey of Western Palestine: Arabic and English Name Lists Collected During the Survey by Lieutenants Conder and Kitchener, R. E. Transliterated and Explained by E.H. Palmer. Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

External links

- Welcome To al-Salihiyya

- al-Salihiyya, Zochrot

- al-Salihiyya, Villages of Palestine

- Survey of Western Palestine, map 4: IAA, Wikimedia commons

- al-Salihiyya, from the Khalil Sakakini Cultural Center