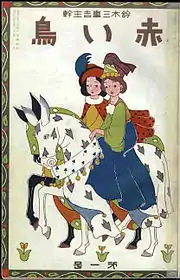

The first issue of Akai tori | |

| Categories | Children's literary magazine |

|---|---|

| Founder | Miekichi Suzuki |

| Founded | 1918 |

| First issue | 1 July 1918 |

| Final issue | 1936 |

| Country | Japan |

| Based in | Tokyo |

| Language | Japanese |

| OCLC | 52282497 |

Akai tori (赤い鳥, Red Bird) was a Japanese children's literary magazine published between 1918 and 1936 in Tokyo, Japan. The magazine has a significant role in establishing dowa and doyo, which refer to new versions of children's fiction, poetry, and songs.[1] In addition, it was pioneer of literary movements, doshinshugi[1] and jidō bungaku (juvenile literature).[2]

History and profile

Akai tori was founded in 1918, and the first issue was published on 1 July of that year.[3] The founder was Miekichi Suzuki, who also published and edited it until 1936.[4][5] Later Nakayama Taichi acquired the publishing company of the magazine.[2] Akai tori was headquartered in Tokyo.[1] Its sister publication was Josei, a women's magazine published between 1922 and 1928.[2]

Akai tori published stories by Ryunosuke Akutagawa, including Spider's Thread and Tu Tze-Chun.[4] Stories written by Niimi Nankichi were also published in the magazine.[6] Miekichi Suzuki published his stories in Akai tori, too.[7] Suzuki's stories were in sharp in contrast to the dominant stories of the day in that his stories featured innocent and introspective children unlike heroic young children commonly covered in popular stories targeting children.[7] In addition, Suzuki translated Mark Twain's The Prince and the Pauper into Japanese and published it in Akai tori in 1925.[8] The magazine also included children's songs such as those written by poet Hakushu Kitahara.[4][9] School children sent their work to the magazine, and Miekichi Suzuki reviewed them and attempted to instruct children how to write essays.[7]

From 1929 to 1931 Akai tori temporarily ceased publication[3] and permanently folded in 1936.[1]

Legacy

The Japan Nursery Rhyme Association named the date of magazine's first issue (1 July) as the Nursery Rhyme Day in Japan.[3] The magazine was studied by different scholars, including Britta Woldering[10] and Elizabeth M. Keith.[1]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Elizabeth M. Keith. "Doshinshugi and realism: A study of the characteristics of the poems, stories and compositions in "Akai tori" from 1918 to 1923". The University of Hong Kong Libraries. Retrieved 30 January 2017.

- 1 2 3 Kazumi Ishii (August 2005). "Josei: A Magazine for the 'New Woman'". Intersections (11).

- 1 2 3 Scott J. Miller (July 2009). Historical Dictionary of Modern Japanese Literature and Theater. Lanham, MD; Toronto; Plymouth: Scarecrow Press. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-8108-6319-4.

- 1 2 3 "The Red Bird". Anipages. 1 February 2006.

- ↑ Rachael Hutchinson (2013). Negotiating Censorship in Modern Japan. Abingdon; New York: Routledge. p. 76. ISBN 978-1-135-06982-7.

- ↑ "Hananoki Village and the Thieves". International Institute for Children's Literature. Retrieved 30 January 2017.

- 1 2 3 Jordan Sand (2006). "Reading Material: The Production of Narratives, Genres and Literary Identities" (PDF). Proceedings of the Association for Japanese Literary Studies. ISSN 1531-5533. OCLC 44991792.

- ↑ Tsuyoshi Ishihara (2016). "The Reception of Mark Twain in Japan from the Meiji Period to the Heisei Period (1860s–2000s)". Literature. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780190201098.013.200. ISBN 978-0-19-020109-8.

- ↑ Gloria Kiester (2005). Games children sing, Japan: 21 children's songs and rhymes. Van Nuys, CA: Alfred Music Publishing. p. 36. ISBN 978-0-7579-3854-2.

- ↑ Nona L. Carter (11 October 2011). "Japanese Children's Magazines, 1888–1949". Dissertation Reviews.