| Acute limb ischaemia | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Acute limb ischemia |

| |

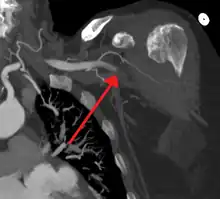

| Acute embolism to the right femoral artery resulting in ischemia | |

| Symptoms | Cold, painful, pulseless limb that cannot move |

| Causes | Embolism, thrombosis |

| Treatment | Thrombectomy, embolectomy, thrombolysis |

| Medication | Thrombolytic drugs |

Acute limb ischaemia (ALI) occurs when there is a sudden lack of blood flow to a limb,[1] within 14 days of symptoms onset.[2] It is different from another condition which is more chronic (more than 14 days)[3] called critical limb ischemia (CLD). CLD is the end stage of peripheral vascular disease where there is still some collateral circulation (alternate circulation pathways} that bring some blood (but inadequate) to the distal parts of the limbs.[2] While limbs in both acute and chronic limb ischemia may be pulseless, a chronically ischemic limb is typically warm and pink due to a well-developed collateral artery network and does not need emergency intervention to avoid limb loss.[4]

Acute limb ischaemia is caused by embolism or thrombosis, or rarely by dissection or trauma.[5] Thrombosis is usually caused by peripheral vascular disease (atherosclerotic disease that leads to blood vessel blockage), while an embolism is usually of cardiac origin.[6] In the United States, ALI is estimated to occur in 14 out of every 100,000 people per year.[7] With proper surgical care, acute limb ischaemia is a highly treatable condition; however, delayed treatment (beyond 6 to 12 hours) can result in permanent disability, amputation, and/or death.

The New Latin term ischaemia as written, is a British version of the word ischemia, and stems from the Greek terms ischein 'to hold'; and haima 'blood'.[8] In this sense, ischaemia refers to the inhibition of blood flow to/through the limb.

Signs and symptoms

Acute limb ischaemia can occur in patients through all age groups. People who smoke tobacco cigarettes and have diabetes mellitus are at a higher risk of developing acute limb ischaemia. Most cases involve people with atherosclerosis problems.[9]

Symptoms of acute limb ischaemia include:

- Pain

- Pallor (pale appearance of the limb)

- Paresthesias (abnormal sensations in the limb)

- Perishingly cold

- Pulselessness

- Paralysis

These symptoms are called "the six P's'";[10][11][12] they are commonly mis-attributed to compartment syndrome. One more symptom would be the development of gangrene. Immediate medical attention should be sought with any of the symptoms.[1]

In late stages, paresthesia is replaced by anesthesia (numbness) due to death of nerve cells.[13] In some cases, gangrene can occur suddenly and spread rapidly,[14] and should be treated within six hours of ischaemia.[15]

Related conditions

When a limb is ischaemic in the non-acute (chronic) setting, the condition is alternatively called peripheral artery disease or critical limb ischaemia, rather than ALI. In addition to limb ischaemia, other organs can become ischaemic, causing:[15]

- Renal ischemia (nephric ischaemia)

- Mesenteric ischaemia

- Cerebral ischaemia

- Cardiac ischaemia

Diagnosis

Once signs and symptoms of acute limb ischemia are identified, the cause and location of the occlusion and its severity need to be addressed. A clinical pulse examination can be done to detect the location of the occlusion by finding the area where the pulse is detected until the area where the pulse disappears. The skin temperature would also be colder in the pulseless area when compared to the area where the pulse is present.[1]

A Doppler evaluation is used to show the extent and severity of the ischaemia by showing flow in smaller arteries. Other diagnostical tools are duplex ultrasonography, computed tomography angiography (CTA), and magnetic resonance angiography (MRA). The CTA and MRA are used most often because the duplex ultrasonography although non-invasive is not precise in planning revascularization. CTA uses radiation and may not pick up on vessels for revascularization that are distal to the occlusion, but it is much quicker than MRA.[1] In treating acute limb ischaemia time is everything.[16]

In the worst cases, acute limb ischaemia progresses to critical limb ischaemia, and results in death or limb loss. Early detection and steps towards fixing the problem with limb-sparing techniques can salvage the limb. Compartment syndrome can occur because of acute limb ischaemia because of the biotoxins that accumulate distal to the occlusion resulting in edema.[1]

Causes

Most acute limb ischemia is caused by embolism (30% of the cases), thrombosis (40% of the cases), thrombosis by popliteal artery aneurysm (5%), major trauma (5%) and vascular graft thrombosis (20%).[2] Rare causes include popliteal entrapment syndrome, adventitial cystic disease, phlegmasia, and thoracic outlet syndrome.

Treatment

Surgery

The primary intervention in acute limb ischaemia is emergency embolectomy using a Fogarty Catheter, providing the limb is still viable within the 4-6h timeframe.[17] Other options include a vascular bypass to route blood flow around the clot.[18]

Medications

Those unsuitable for surgery may receive thrombolytics. In the past, streptokinase was the main thrombolytic chemical. More recently, drugs such as tissue plasminogen activator, urokinase, and anistreplase have been used in their place. Mechanical methods of injecting the thrombolytic compounds have improved with the introduction of pulsed spray catheters—which allow for a greater opportunity for patients to avoid surgery.[19][20] Pharmacological thrombolysis requires a catheter to be inserted into the affected area, attached to the catheter is often a wire with holes to allow for a wider dispersal area of the thrombolytic agent. These agents lyse the ischemia-causing thrombus quickly and effectively.[21] However, the efficacy of thrombolytic treatment is limited by hemorrhagic complications. Plasma fibrinogen level has been proposed as a predictor of these hemorrhagic complications. However, based on a systematic review of the available literature until January 2016, the predictive value of plasma is unproven.[22]

Mechanical thrombolysis

Another type of thrombolysis disrupts the clot mechanically using either saline jets or, more recently, ultrasound waves. Saline jets dislodge the clot using the Bernoulli effect. Ultrasound waves, emitted at low frequency, create a physical fragmentation of the thrombus.[23]

Considerations in treatment

The best course of treatment varies from case to case. The physician must take into account the details in the case before deciding on the appropriate treatment. No treatment is effective for every patient.[13]

Treatment depends on many factors, including:

- Location of lesions

- Anatomy of lesions

- Individual risk factors

- Procedural risk

- Clinical presentation of symptoms

- Duration of symptoms

- etc.[19]

Epidemiology

The major cause of acute limb ischaemia is arterial embolism (80%), while arterial thrombosis is responsible for 20% of cases. In rare instances, arterial aneurysm of the popliteal artery has been found to create a blood clot or embolism resulting in ischaemia.[24]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Walker T. Gregory (2009). "Acute Limb Ischemia". Techniques in Vascular and Interventional Radiology. 12 (2): 117–129. doi:10.1053/j.tvir.2009.08.005. PMID 19853229.

- 1 2 3 Olinic DM, Stanek A, Tătaru DA, Homorodean C, Olinic M (August 2019). "Acute Limb Ischemia: An Update on Diagnosis and Management". Journal of Clinical Medicine. 8 (8): 1215. doi:10.3390/jcm8081215. PMC 6723825. PMID 31416204.

- ↑ Fabiani I, Calogero E, Pugliese NR, Di Stefano R, Nicastro I, Buttitta F, Nuti M, Violo C, Giannini D, Morgantini A, Conte L, Barletta V, Berchiolli R, Adami D, Ferrari M, Di Bello V (July 2018). "Critical Limb Ischemia: A Practical Up-To-Date Review". Angiology. 69 (6): 465–474. doi:10.1177/0003319717739387. PMID 29161885. S2CID 22281024.

- ↑ Farber, A (12 July 2018). "Chronic Limb-Threatening Ischemia". The New England Journal of Medicine. 379 (2): 171–180. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp1709326. PMID 29996085. S2CID 51623293.

- ↑ Creager, Mark A.; Kaufman, John A.; Conte, Michael S. (2012). "Acute Limb Ischemia". New England Journal of Medicine. 366 (23): 2198–2206. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp1006054. PMID 22670905.

- ↑ Klonaris, C; Georgopoulos, S; Katsargyris, A; Tsekouras, N; Bakoyiannis, C; Giannopoulos, A; Bastounis, E (March 2007). "Changing patterns in the etiology of acute lower limb ischemia". International Angiology. 26 (1): 49–52. PMID 17353888.

- ↑ Dormandy J, Heeck L, Vig S (June 1999). "Acute limb ischemia". Semin Vasc Surg. 12 (2): 148–53. PMID 10777242.

- ↑ "Ischaemia." Merriam-Webster. Last modified 2012. http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/ischemia?show=0&t=1334804041

- ↑ Brooks Marcus; Jenkins Michael P (2008). "Acute and chronic ischaemia of the limb". Surgery (Oxford). 26 (1): 17–20. doi:10.1016/j.mpsur.2007.10.012.

- ↑ Brearley, S (May 8, 2013). "Acute leg ischaemia". BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.). 346: f2681. doi:10.1136/bmj.f2681. PMID 23657181. S2CID 33617691.

- ↑ "CKS is only available in the UK". NICE. Retrieved 2020-10-15.

- ↑ "Acute Limb Ischaemia - Clinical Features - Management". TeachMeSurgery. Retrieved 2020-10-15.

- 1 2 Obara, H.; Matsubara, K.; Kitagawa, Y. (25 December 2018). "Acute Limb Ischemia". Annals of Vascular Diseases. 11 (4): S5–S67443–448. doi:10.3400/avd.ra.18-00074. PMC 6326052. PMID 30636997.

- ↑ Norgren, L.; Hiatt, W.R.; Dormandy, J.A.; Harris, K.A.; Fowkes, F.G.R. (1 January 2007). "Inter-Society Consensus for the Management of Peripheral Arterial Disease (TASC II)". Journal of Vascular Surgery. 45 (1): S5–S67. doi:10.1016/j.jvs.2006.12.037. PMID 17223489. Retrieved June 25, 2021.

- 1 2 "Acute Limb Ischemia". The Lecturio Medical Concept Library. Retrieved 2021-06-25.

- ↑ Fluck, F.; Augustin, A.M.; Augustin, T.; Kickuth, R (April 2020). "Current Treatment Options in Acute Limb Ischemia". RöFo. 192 (4): 319–326. doi:10.1055/a-0998-4204. PMID 31461761.

- ↑ Goldberg, Andrew (2012). Surgical Talk: Lecture Notes in Undergraduate Surgery. Imperial College Press. p. 234. ISBN 978-1-84816-6141.

- ↑ Bowley, Douglas, and Andrew Kingsnorth, eds. Fundamentals of Surgical Practice: A Preparation Guide for the Intercollegiate Mrcs Examination. 3rd ed. N.p.: Cambridge University Press, 2011. 506-11. Web. 20 Apr. 2012.

- 1 2 Andaz S.; Shields D.A.; Scurr J.H.; Smith P.D. Coleridge (1993). "Thrombolysis in acute lower limb ischaemia". European Journal of Vascular Surgery. 7 (6): 595–603. doi:10.1016/S0950-821X(05)80702-9. PMID 8270059.

- ↑ ABC of Arterial and Venous Disease: Acute Limb Ischaemia Ken Callum and Andrew Bradbury BMJ: British Medical Journal, Vol. 320, No. 7237 (Mar. 18, 2000), pp. 764-767

- ↑ Wardlaw J.M.; Warlow C.P. (1992). "Thrombolysis in acute ischemic stroke: does it work?". Stroke. 23 (12): 1826–1839. doi:10.1161/01.str.23.12.1826. PMID 1448835.

- ↑ Poorthuis, Michiel H. F.; Brand, Eelco C.; Hazenberg, Constantijn E. V. B.; Schutgens, Roger E. G.; Westerink, Jan; Moll, Frans L.; de Borst, Gert J. (2017-03-05). "Plasma fibrinogen level as a potential predictor of hemorrhagic complications after catheter-directed thrombolysis for peripheral arterial occlusions". Journal of Vascular Surgery. 65 (5): 1519–1527.e26. doi:10.1016/j.jvs.2016.11.025. ISSN 1097-6809. PMID 28274749.

- ↑ Sean P. Lyden, Endovascular Treatment of Acute Limb Ischemia: Review of Current Plasminogen Activators and Mechanical Thrombectomy Devices PERSPECT VASC SURG ENDOVASC THER December 2010 22: 219-222, first published on March 16, 2011

- ↑ Mitchell ME, Carpenter JP. Overview of acute arterial occlusion of the extremities (acute limb ischemia). In: Post TW, ed. UpToDate. Waltham, MA: UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/overview-of-acute-arterial-occlusion-of-the-extremities-acute-limb-ischemia?source=search_result&search=Classification%20of%20acute%20extremity%20ischemia&selectedTitle=1∼90#H506059593. Last updated May 31, 2016. Accessed December 13, 2016.