The Aconcagua mummy is an Incan capacocha mummy of a seven-year-old boy, dated to around the year 1500.[1] The mummy is well-preserved, due to the extreme cold and dry conditions of its high altitude burial location.[2] The frozen mummy was discovered by hikers in 1985 at 5,300 m (17,400 ft) on Aconcagua in Mendoza, Argentina.[1][2]

Discovery

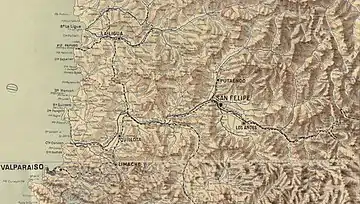

In 1985, the body of the Aconcagua mummy was located by mountaineers at the bottom of Pirámide Mountain, the southwestern portion of the Aconcagua Mountain. Upon its discovery, the hikers contacted local authorities, allowing professionals to excavate the mummy.[1]

Scientific analysis

Burial practices

The Aconcagua mummy was buried inside a semicircular stone structure[3] and found covered in vomit, red pigment, and fecal remains.[4] The body was wrapped in textiles in a style derived from central coastal Peru.[5] Although the style of the textiles the boy was wrapped in are dated to coastal Peru, isotopic evidence suggests that the boy was likely raised in the Highlands.[4] Six statuettes were also found buried with the body.[1] The burial of the Aconcagua mummy contained a multitude of grave goods. Female capacocha mummies were often buried with more honorable and extravagant grave goods, which made the male burial of the Aconcagua distinct.[4]

Isotopic analysis

When analyzing the isotopes of the Aconcagua mummy, scientists concentrated specifically on carbon, nitrogen and sulfur.[4] The analysis shows that in the year and a half before his death, his diet consisted primarily of maize, quinoa, capsicum, potatoes, and terrestrial meat. Before the child was chosen for the sacrifice his diet was primarily marine-based.[4] The presence of achiote was also found inside his stomach and colon.[5] Because of the conflicting results of the isotopes suggesting the child was from the summits but survived off a marine based diet, researchers tried to pinpoint the ethnicity of the child. In this attempt, a hair sample from the mummy was used. Unfortunately, this isotopic analysis yielded little information about the child's ethnicity, so researchers concluded he was likely from Pacific regions ranging from Southern Peru to central Chile.[4]

Capacocha

The Capacocha was the ritual sacrifices of young boys and girls in the Inca Empire. Those chosen to be sacrificed were seen as the most serene children in the Empire, making them worthy of sacrifice.[6][1] The most substantial requirement to be chosen for the sacrifice, was to be a virgin. This alludes to the serenity and perfection of the children and infants picked to be tributed to the gods. For a year before the sacrifice, the children were fed the most prestigious diets. The diets revolved solely around maize and charqui, meat from a llama.[7] Many parents felt sorrow when forced to give up their children to the sacrifice, but were forbidden to show grief during the event. Others felt the sacrifice was a great honor and even offered their children to the gods.[7] These children faced their demise at the end of a long trek to the summits of the Andes, where they experienced blunt head trauma causing them to die, or they were buried alive.[4] Each child was often buried with a variety of grave goods, as an offering to the gods. The funerary goods buried along the children depended on the importance of the shrine and sometimes even contained animals buried alongside the children.[8]

Archaeogenetics

In 2015, DNA was extracted from a 350 mg sample from one of his lungs.[1] His mtDNA lineage belongs to a subgroup of Haplogroup C1b, the previously unidentified C1bi (i for Inca).[1] His mtDNA lineage contains 10 distinct mutations from C1b.[1] The researchers determined that Haplogroup C1bi likely arose around 14,300 years ago.[1] An individual from the Wari Empire was found to be a match for this previously unidentified haplogroup.[1][2] In 2018, researchers sequenced the genome of the Aconcagua mummy from a 100 mg sample from one of his lungs.[9] His Y-DNA lineage belongs to Haplogroup Q-M3.[10] His specific Y-DNA haplogroup is closest matched by the Choppca people from Huancavelica, a Quechua speaking population, and clusters closer to modern Quechua speaking peoples than Aymara speaking peoples.[10] Overall, the genome of the Aconcagua mummy clusters with modern Andean populations.[11]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Gómez-Carballa & Catelli 2015.

- 1 2 3 Wade 2015.

- ↑ Ceruti 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Faux 2012.

- 1 2 Cassman 2007, p. 144.

- ↑ Andrushko, Valerie A.; Buzon, Michele R.; Gibaja, Arminda M.; McEwan, Gordon F.; Simonetti, Antonio; Creaser, Robert A. (2011-02-01). "Investigating a child sacrifice event from the Inca heartland". Journal of Archaeological Science. 38 (2): 323–333. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2010.09.009. ISSN 0305-4403.

- 1 2 Rubio, María Del Carmen Martín (2009-12-31). "La cosmovisión religiosa andina y el rito de la Capacocha". Investigaciones Sociales. 13 (23): 187–201. doi:10.15381/is.v13i23.7229. ISSN 1818-4758.

- ↑ Bray, Tamara L.; Minc, Leah D.; Ceruti, María Constanza; Chávez, José Antonio; Perea, Ruddy; Reinhard, Johan (2005-03-01). "A compositional analysis of pottery vessels associated with the Inca ritual of capacocha". Journal of Anthropological Archaeology. 24 (1): 82–100. doi:10.1016/j.jaa.2004.11.001. hdl:11336/94308. ISSN 0278-4165.

- ↑ Moreno-Mayar et al. 2018, p. 12 (Supplementary).

- 1 2 Salas et al. 2018.

- ↑ Moreno-Mayar et al. 2018, p. 21 (Supplementary).

Bibliography

- Cassman, Vicki (2007). Human Remains: Guide for Museums and Academic Institutions. Rowman Altamira. ISBN 978-0759109551.

- Ceruti, Maria Constanza (2015). "Frozen Mummies from Andean Mountaintop Shrines: Bioarchaeology and Ethnohistory of Inca Human Sacrifice". BioMed Research International. 2015: 439428. doi:10.1155/2015/439428. ISSN 2314-6133. PMC 4543117. PMID 26345378.

- Faux, Jennifer L. (2012). "Hail the Conquering Gods: Ritual Sacrifice of Children in Inca Society". Journal of Contemporary Anthropology. 3 (1).

- Gómez-Carballa, Alberto; Catelli, Laura (November 12, 2015). "The complete mitogenome of a 500-year-old Inca child mummy". Scientific Reports. 5: 16462. Bibcode:2015NatSR...516462G. doi:10.1038/srep16462. PMC 4642457. PMID 26561991.

- Moreno-Mayar, J. Víctor; Vinner, Lasse; de Barros Damgaard, Peter; de la Fuente, Constanza; Chan, Jeffrey; Spence, Jeffrey P.; Allentoft, Morten E.; Vimala, Tharsika; Racimo, Fernando; Pinotti, Thomaz; Rasmussen, Simon; Margaryan, Ashot; Iraeta Orbegozo, Miren; Mylopotamitaki, Dorothea; Wooller, Matthew; Bataille, Clement; Becerra-Valdivia, Lorena; Chivall, David; Comeskey, Daniel; Devièse, Thibaut; Grayson, Donald K.; George, Len; Harry, Harold; Alexandersen, Verner; Primeau, Charlotte; Erlandson, Jon; Rodrigues-Carvalho, Claudia; Reis, Silvia; Bastos, Murilo Q. R.; Cybulski, Jerome; Vullo, Carlos; Morello, Flavia; Vilar, Miguel; Wells, Spencer; Gregersen, Kristian; Hansen, Kasper Lykke; Lynnerup, Niels; Mirazón Lahr, Marta; Kjær, Kurt; Strauss, André; Alfonso-Durruty, Marta; Salas, Antonio; Schroeder, Hannes; Higham, Thomas; Malhi, Ripan S.; Rasic, Jeffrey T.; Souza, Luiz; Santos, Fabricio R.; Malaspinas, Anna-Sapfo; Sikora, Martin; Nielsen, Rasmus; Song, Yun S.; Meltzer, David J.; Willerslev, Eske (November 8, 2018). "Early human dispersals within the Americas". Science. American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS). 362 (6419): eaav2621. Bibcode:2018Sci...362.2621M. doi:10.1126/science.aav2621. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 30409807.

- Salas, Antonio; Catelli, Laura; Pardo-Seco, Jacobo; Gómez-Carballa, Alberto; Martinón-Torres, Federico; Roberto-Barcena, Joaquín; Vullo, Carlos (2018). "Y-chromosome Peruvian origin of the 500-year-old Inca child mummy sacrificed in Cerro Aconcagua (Argentina)". Science Bulletin. Elsevier BV. 63 (22): 1457–1459. Bibcode:2018SciBu..63.1457S. doi:10.1016/j.scib.2018.08.009. ISSN 2095-9273. PMID 36658824.

- Wade, Lizzie (12 November 2015). "Inca child mummy reveals lost genetic history of South America". AAAS. Retrieved 17 November 2015.