Achille Starace | |

|---|---|

| |

| Secretary of the National Fascist Party | |

| In office 12 December 1931 – 31 October 1939 | |

| Leader | Benito Mussolini |

| Preceded by | Giovanni Giuriati |

| Succeeded by | Ettore Muti |

| President of the Italian National Olympic Committee | |

| In office 5 May 1933 – 31 October 1939 | |

| Preceded by | Leandro Arpinati |

| Succeeded by | Rino Parenti |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 18 August 1889 Sannicola, Kingdom of Italy |

| Died | 29 April 1945 (aged 55) Milan, Kingdom of Italy |

| Political party | National Fascist Party |

Achille Starace (Italian pronunciation: [aˈkille staˈraːtʃe]; 18 August 1889 – 29 April 1945) was a prominent leader of Fascist Italy before and during World War II.

Early life and career

Starace was born in Sannicola, province of Lecce, in southern Apulia. His father was a wine and oil merchant.

Starace attended the Lecce Technical Institute and earned a degree in accounting. In 1909 he joined the Italian Royal Army (Regio Esercito) and by 1912 had become a second lieutenant (sottotenente) of the Bersaglieri. A dedicated bellicist, he entered singlehanded in a brawl with pacifist demonstrators at the Biffi Cafe in Milan in August 1914 and gained quite a reputation by this action.

Seeing action during World War I, Starace was highly decorated for his service, winning one Silver Medal of Military Valor plus four bronze. After the war, he left the army and moved to Trento, where he first came into contact with the growing Fascist movement. He also joined the Freemason lodge La Vedetta ("The Sentinel") in Udine in March 1917.

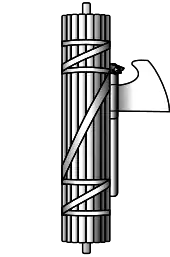

An ardent nationalist, Starace joined the Fascist movement in Trento in 1920 and quickly became its local political secretary. In 1921, his efforts caught the attention of Benito Mussolini, who put Starace in charge of the Fascist organization in Venezia Tridentina. In October 1921, Starace became vice-secretary of the National Fascist Party (Partito Nazionale Fascista, or PNF). In 1922, Starace participated in the March on Rome (Marcia su Roma), leading a squad of Blackshirts (Camicie Nere, or CCNN) in support of Mussolini.

Prominence

Later in 1922, Starace was appointed party inspector of Sicily and made a member of the Executive Committee of the PNF. In 1923, after resigning as vice-secretary of the party, he was made commander of the National Security Volunteer Militia (Milizia Volontaria per la Sicurezza Nazionale or MVSN) in Trieste. The MVSN was an all-volunteer militia created to organize former Blackshirts.

In 1924, Starace was elected to the Italian Chamber of Deputies and made national party inspector. In 1926, Achille Starace once again became vice-secretary of the PNF, and, in 1928, he was appointed secretary of the Milan branch of the party.

Party secretary

In 1931, his career reached its peak when he was made party secretary of the PNF. He was appointed to the position primarily for his unquestioning, fanatical loyalty to Mussolini. As secretary, Starace staged huge parades and marches, proposed Anti-Semitic racial segregation measures, and greatly expanded Mussolini's cult of personality.

Although Starace was successful in increasing party membership, he failed in the later years of his tenure as secretary to reorganize the Italian Fascist Youth Organization (Opera Nazionale Balilla) along the lines of the Hitler Youth (Hitler-Jugend). He also failed to inspire a nationwide enthusiasm for Fascism on par with the popularity that the Nazi Party enjoyed in Germany. Starace served as secretary for a total of eight years. This was longer than any other Secretary had served. But, by the mid-1930s, he had gained numerous enemies in the party hierarchy.

Role in the invasion of Ethiopia

In 1935, Starace, a Colonel, took a leave of absence as PNF Party Secretary to participate in the Italian invasion of Ethiopia and fought on the northern front. In March 1936, after the Battle of Shire, he was given command of a mixed group of Blackshirts and Bersaglieri being assembled in Asmara, Eritrea. Later that month, Starace and his truck-transportable "mechanized column" prepared to advance over rough tracks to seize Gondar, the capital of Begemder Province. Before setting out, "the Panther Man" (L'uomo pantera) gave the following speech to his men:

Soldiers, this is the most risky, most difficult and most important venture of the campaign. Don't waste a shot. We are carrying all the ammunition we are going to have on this trip. This column must be like an electric live wire. Death to the touch! Truck drivers must learn to keep to the right of the road under pain of severe penalties…

Britain is a rich country, Italy is a poor country, but the people of poor countries have hard muscles. The only way to explain the action of the English is that they thought they had only to mass a war fleet in the Mediterranean and Premier Mussolini would take off his hat and bow in submission.

Instead he reared up like a thoroughbred horse and sent his soldiers into Africa. Viva Il Duce![1]

The roadbuilding skills of Starace's men played an equally important role to their combat prowess. The following morning, April 1, Starace and the column entered Gondar in triumph and two days later reached Lake Tana, securing the border region with British Sudan. The East African Fast Column (Colonna Celere dell'Africa Orientale) had covered approximately 120 km in three days.

Return to party secretary

After Ethiopia, Starace resumed his duties as Party Secretary. He continued to be controversial. For example, he decreed that all party flags must be made from an Italian-created textile fabric called "Lanital." Based on casein, a phosphoprotein commonly found in mammalian milk, Lanital was invented in 1935 and, according to Starace, it was a "product of Italian ingenuity." In 1936, Dino Grandi, the Italian Ambassador to Great Britain, appeared in London wearing a suit said to have been made from forty-eight pints of skimmed milk.[2]

During the Munich Crisis in 1938 which ended with Nazi Germany's annexation of the Sudetenland, Starace was a vocal proponent that the French should agree to cede Tunisia to Italy.

Starace in Italian sport

Starace was a sports fanatic and instituted president of the CONI (Italian National Olympic Committee). He is remembered for such unlikely sports stunts as jumping through a fire circle at the Marmi Stadium in 1938 or horse jumping over a saloon car.

He wanted party officials to look virile and fit and on official ceremonies had them parading at the bersaglieri pace, an Italian variant of goose stepping.

He is specially and more significantly remembered also for a policy of enrollment of the Italian people (either young or not) in Fascist party-linked organizations that bore some semblance to the Scout movement: Opera Balilla, Figli della lupa, Avanguardisti, Giovane fascista and the labour-related Organizzazione del Dopolavoro (after-work sports).

Sports were of particular importance in Fascist propaganda, heavily exploiting the successes of Italian athletes in international competitions (like boxer Primo Carnera or the Italy national football team), and Starace was quite instrumental in this field, tackling both the mass organisation and the elite side of Italian sports.

Dismissal

In October 1939, Starace was finally dismissed as party secretary in favor of the popular aviator Ettore Muti. He was made chief of staff of the Blackshirts and he held this position until being dismissed for incompetence in May 1941. He was succeeded by Enzo Galbiati.

Imprisonment and death

In 1943, following the demise of Mussolini's regime, Starace was arrested by Pietro Badoglio's Royalist government. He was arrested even though his real power under Mussolini had ended two years earlier.

After unsuccessfully attempting to regain Mussolini's favor in the German-backed Italian Social Republic of Salò, Starace was again arrested. This time he was imprisoned in a concentration camp in Verona and was arrested by his former colleagues on charges that he had weakened the party during his tenure as Party Secretary.

Starace was eventually released and moved to Milan. On 29 April 1945, during his morning jog, he was recognized and captured by anti-Fascist Italian partisans. Starace was taken to Piazzale Loreto and shown the body of Mussolini, which he saluted just before he was executed. His body was subsequently strung up alongside Mussolini's.

In Italian daily life

Starace was one of the main objects of political satire and popular jokes under Fascism. The citations of his sayings are innumerable, and most of them, if separated for a moment from the tragic historical circumstances of their origin, demonstrate that Starace had moved away from practical sense in his pursuit of a path for propaganda for the regime:

"I wonder why the expectation is still to consider the end of the year to conform to the metric of 31 December rather than 28 October [the date of the March on Rome in 1922]. The attachment to this custom is indicative of non-fascist mentality."

"At the word" comizio (roman for meeting) "from now on please replace the word" gathering of propaganda. "The word comizio reminds us of times passed forever."

On one occasion he had to preside officially at a high-level medical symposium, but, much to the displeasure of the participants, turned up one hour late for the opening address, explaining that he had been on his daily hour of horse riding. Far from offering excuses to the infuriated audience, he sharply cut short the protests with a famous phrase: "do less medicals, just drop your books and do more gymnastics, dedicate yourself to equestrian sports" (datevi all'ippica in Italian). The motto stuck and in the 21st century Datevi all'ippica still is a proverbial catchphrase to tell someone that he is incompetent and should try his hand at some unskilled job.

He tried to phase some Anglo-Saxon and foreign words and manners out of Italian daily life, with a moderate degree of success: The word 'volleyball' was (and still is) replaced in Italian usage by 'pallavolo', a word Starace is said to have invented. Similarly 'tramezzino' was substituted for 'sandwich' and 'autorimessa' for 'garage', but the abstruse Italian replacements for words like 'cognac', 'bar', 'cocktail', 'tennis', and so forth never caught on. The "British" handshake greeting was forbidden and replaced by the compulsory raised-arm Roman-style salute. He even tried to have the "Viva Il Duce" motto made compulsory as the ending in public and private correspondence but Mussolini bluntly put a stop to this particular move, which he found ludicrous, saying: "how stupid would be a condolence letter that went: 'Harry is dead. Viva il Duce'".

He insisted on having the plan of Quartiere Romano di San Basilio (three blocks of council housing flats) shaped in such a way that they would form a gigantic D U C E[3] when seen from a passing aircraft, as an homage to Mussolini.

All in all he was considered by the other high-ranking Fascist gerarchi as a devoted but not too bright follower of the Duce, and Mussolini himself said of Starace "Un cretino, sí, ma un cretino obbediente" ("a cretin, yes, but an obedient cretin").

About his fanatical devotion to Mussolini, his own daughter later said of him: 'He breathed only by the Duce's order.'

The man in the street was more or less of the same opinion and Starace was regularly lampooned almost openly by student songs and poems that circulated almost freely despite the Fascist regime and the political police.

It was said, about the "bestiary" symbolic of Fascism: "The wolf, which is voracious; the lion which is ferocious; the eagle, which is rapacious, the goose; which is Starace." («La lupa, che è vorace; il leone ch'è feroce; l'aquila, che è rapace; l'oca, che è Starace»)

A mock epitaph was coined by students, written on walls even during the Fascist period, which read: "Here lies Starace, dressed in orbace [wool, see below], capable of nothing, Requiescat in pace."( «È morto Starace, vestito d'orbace, di nulla capace, requiescat in pace»). Another variation of this rhyme read: "Here lies Starace / clad in orbace / rapacious in peace / in war a fleeting type / in bed a pugnacious one," («Qui giace Starace / vestito d'orbace / in pace rapace / in guerra fugace / a letto pugnace») recalling the exhortation he addressed his compatriots, according to which "all party organs work: have to work so, even the genitals." (Orbace was a special sort of raw wool cloth made in Sardegna that Starace had made compulsory for Fascist party officials' uniforms, as part of the Fascist autarky policy, and is said to have been very itchy.)

Galeazzo Ciano, Mussolini's son in law and foreign affairs minister wrote of Starace in his diary: "The Italians are people that may pardon anybody who treated them wrong... but they won't pardon somebody who has been breaking their... boxes (polite substitute for... balls)".

When his grandchild, socialite Giò Stajano publicly underwent a male-to-female gender transition, she released her first post-operation interview with the journalist Francesco D. Caridi of Il Borghese, who asked her "Who knows what your grandfather Achille Starace would say if he saw you, he who wanted all Italians to be male and strong... ". Stajano jokingly replied: "He would say that after so much virility in the family, you need a little relaxation".[4]

Awards and decorations

- Knight of the Order of Saints Maurice and Lazarus

- Officer of the Military Order of Savoy (24 August 1936), previously a Knight (17 May 1919)

- Commander of the Order of the Crown of Italy

- Silver Medal of Military Valour

- Bronze Medal for Military Valour, 4 times

- Cross of Merit of War - Grant for Military Valor

- Cross of Merit of War

- Commemorative Medal for the Italo-Austrian War 1915–1918

- Commemorative Medal of the Unity of Italy

- Allied Victory Medal 1914-1918

- Commemorative Medal of the March on Rome

- in gold "on the occasion of his appointment as Secretary of the PNF" (7 December 1931)

- in silver "awarded to the 19 commanders of the columns of the organized teams to converge on Rome" (1923)

- Cross of seniority (20 years) in the Voluntary Militia for National Security

- Grand Cross of the Order of the German Eagle

See also

References

- ↑ Time, 13 April 1936

- ↑ Time, August 29, 1938

- ↑ "Elementi immobiliari dallo stile suggestivo a San Basilio". 26 July 2018. Retrieved 29 April 2020.

- ↑ "Addio a Giò Stajano, prima trans d'Italia". la Repubblica (in Italian). 27 July 2011. Archived from the original on 25 June 2018. Retrieved 6 February 2021.

Sources

- Carlo Galeotti, Achille Starace e il vademecum dello stile fascista, Rubbettino, 2000 ISBN 88-7284-904-7

External links

- Time, April 13, 1936 "Hit & Run"

- Time, August 29, 1938 "Wool from Cows"

- The New Yorker, Description of his death