| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

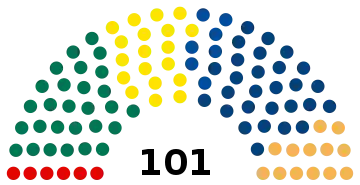

101 seats in the Riigikogu 51 seats needed for a majority | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

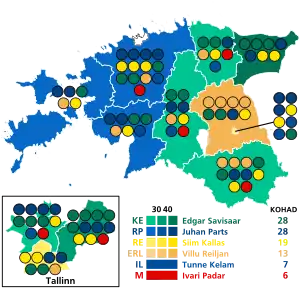

Results by electoral district | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Parliamentary elections were held in Estonia on 2 March 2003. The newly elected 101 members of the 10th Riigikogu assembled at Toompea Castle in Tallinn within ten days of the election. Two opposing parties won the most seats, with both the Centre Party and Res Publica Party winning 28 seats in the Riigikogu. Res Publica was able to gain enough support in negotiations after the elections to form a coalition government.

Background

Following the 1999 election, a Triple Alliance coalition government was formed by Mart Laar of the Pro Patria Union, including the Reform Party and the Moderates.[1]

By late 2001, scandals related to the privatization of state-owned enterprises had made the government unpopular, and relations between the Pro Patria Union and the Reform Party deteriorated. In December 2001, the Reform Party entered a coalition with the Centre Party in Tallinn, as a result of which Edgar Savisaar became the mayor. This happened after Reform had left the same Triple Alliance governing coalition in Tallinn. Prime Minister Mart Laar decided to resign, as he felt that the national level Triple Alliance government had essentially collapsed[2][3][4]

Following that, a new coalition government was formed between the Reform Party and the Centre Party, with Siim Kallas from the Reform Party of Estonia as Prime Minister.[5]

On 26 November 2002 the President of Estonia, Arnold Rüütel, set 2 March 2003 as the election date.[6] 947 candidates from 11 political parties contested the election as well as 16 independents.[7]

Electoral system

The 101 members of the Riigikogu (Parliament of Estonia) were elected using a form of proportional representation for a four-year term. The seats were allocated using a modified D'Hondt method. The country is divided into twelve multi-mandate electoral districts. There is a nationwide threshold of 5% for party lists, but if the number of votes cast for a candidate exceeds or equals the simple quota (which shall be obtained by dividing the number of valid votes cast in the electoral district by the number of mandates in the district) the candidate is elected.

| District number | Electoral District | Seats |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Haabersti, Põhja-Tallinn and Kristiine districts in Tallinn | 8 |

| 2 | Kesklinn, Lasnamäe and Pirita districts in Tallinn | 10 |

| 3 | Mustamäe and Nõmme districts in Tallinn | 8 |

| 4 | Harjumaa (without Tallinn) and Raplamaa counties | 12 |

| 5 | Hiiumaa, Läänemaa and Saaremaa counties | 7 |

| 6 | Lääne-Virumaa county | 6 |

| 7 | Ida-Virumaa county | 8 |

| 8 | Järvamaa and Viljandimaa counties | 9 |

| 9 | Jõgevamaa and Tartumaa counties (without Tartu) | 8 |

| 10 | Tartu city | 8 |

| 11 | Võrumaa, Valgamaa and Põlvamaa counties | 9 |

| 12 | Pärnumaa county | 8 |

Contesting parties

The Estonian National Electoral Committee announced that 11 political parties and 16 individual candidates registered to take part in the 2003 parliamentary election. Their registration numbers and order were determined by the order of registration.[8][7]

Campaign

|

|---|

Opinion polls showed the Centre Party led by the mayor of Tallinn, Edgar Savisaar, with a small lead in the run up to the election.[13] They were expected to gain support from among those who had not benefited from the rapid economic reforms that had taken place over the last decade.[14] However their populism and their lack of a clear policy on whether Estonia should join the European Union meant they were likely to struggle to form a coalition after the election.[14]

The leading critics of the Centre Party were from the new conservative Res Publica Party, which had only been formed in 2002.[5] Res Publica's campaign focused on the need to address crime and corruption[5] and they portrayed themselves as being a change to the older political parties.[14] Res Publica had performed strongly in the 2002 local elections after being formed from the youth wings of some of the other right wing political parties.[14]

A leading issue in the election was the tax system with the Centre Party pledging to scrap the flat tax and change it to a progressive tax system.[15] Both Res Publica and the Reform Party opposed this, with the Reform Party calling for the tax rate to be cut significantly.[15] The personalities of the various party leaders were also a significant part of the campaign, with opponents particularly attacked the Centre Party leader Edgar Savisaar.[15] Savisaar had quit as interior minister in 1995 after being accused of taping rival politicians[5] and during the campaign the media raised questions over the financing of his campaign.[15]

Results

The results saw the Centre Party win the most votes but they were only 0.8% ahead of the new Res Publica party.[16] As a result, both parties won 28 seats, which was a disappointment for the Centre Party who had expected to win the most seats.[17] Altogether the right of centre parties won 60 seats, compared to only 41 for the left wing, and so were expected to form the next government.[5][18] Voter turnout was higher than expected at 58%.[15] The Russian minority parties lost representation in parliament, with most of such voter switching to Estonian parties of the left (Estonian Centre Party) or some to the non-nationalist right (Reform Party).

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Votes | % | Seats | +/– | |

| Estonian Centre Party[lower-alpha 2] | 125,709 | 25.40 | 28 | 0 | |

| Res Publica Party | 121,856 | 24.62 | 28 | New | |

| Estonian Reform Party | 87,551 | 17.69 | 19 | +1 | |

| People's Union of Estonia[lower-alpha 3] | 64,463 | 13.03 | 13 | +6 | |

| Pro Patria Union | 36,169 | 7.31 | 7 | –11 | |

| Moderate People's Party | 34,837 | 7.04 | 6 | –11 | |

| Estonian United People's Party | 11,113 | 2.25 | 0 | –6 | |

| Estonian Christian People's Party | 5,275 | 1.07 | 0 | 0 | |

| Estonian Independence Party | 2,705 | 0.55 | 0 | New | |

| Social Democratic Labour Party | 2,059 | 0.42 | 0 | New | |

| Russian Party in Estonia[lower-alpha 4] | 990 | 0.20 | 0 | 0 | |

| Independents | 2,161 | 0.44 | 0 | 0 | |

| Total | 494,888 | 100.00 | 101 | 0 | |

| Valid votes | 494,888 | 98.84 | |||

| Invalid/blank votes | 5,798 | 1.16 | |||

| Total votes | 500,686 | 100.00 | |||

| Registered voters/turnout | 859,714 | 58.24 | |||

| Source: Nohlen & Stöver[19] | |||||

- ↑ As part of Estonian United People's Party

- ↑ The Estonian Centre Party list included members of the Estonian Pensioners' Party.

- ↑ The People's Union of Estonia list included members of the New Estonia Party.

- ↑ The Russian Party in Estonia list included members of the Party of Estonian Unity, Russian Baltic Party in Estonia and the Russian Unity Party.

Aftermath

Both the Centre and Res Publica parties said that they should get the chance to try and form the next government,[20] while ruling out any deal between themselves.[21] President Rüütel had to decide who he should nominate as Prime Minister and therefore be given the first chance at forming a government.[21] On the 2 April he invited the leader of the Res Publica party, Juhan Parts to form a government[22] and after negotiations a coalition government composed of Res Publica, the Reform Party and the People's Union of Estonia was formed on the 10 April.[22] The government has also been referred to as the Harmony coalition.[23][24][25][26]

References

- ↑ Estonia: Parliamentary Chamber: Riigikogu: Elections held in 1999 Inter-Parliamentary Union

- ↑ "Kallas: kolmikliit peab jätkama". Delfi (in Estonian). Retrieved 2023-08-21.

- ↑ Muuli, Kalle (2014). Hainsalu, Esta (ed.). Kodanike riik: reformierakond loomisest kuni tänapäevani. Tallinn: Menu Kirjastus. ISBN 978-9949-549-07-8.

- ↑ "Kuidas kolmikliit valitsust moodustas". Äripäev (in Estonian). Retrieved 2023-08-21.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Deadlock in Estonia election". BBC News Online. 2003-03-03. Retrieved 2009-06-01.

- ↑ "Baltic Report: December 6, 2002". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. 2002-12-06. Retrieved 2009-06-01.

- 1 2 "Baltic Report: January 28, 2003". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. 2003-01-28. Retrieved 2009-06-01.

- ↑ Heinsalu, Alo; Koitmäe, Arne; Mandre, Leino; Pilving, Mihkel; Vinkel, Priit; Eero, Gerli; Eesti Rahvusraamatukogu; Eesti, eds. (2011). Valimised Eestis: statistikat ja selgitusi. Tallinn: Vabariigi Valimiskomisjon.

- ↑ Eesti Päevaleht 20 June 2008: Kaitsepolitsei aastaraamat: Vene luure tegi mullu Eestis usinalt tööd Archived 2008-06-30 at the Wayback Machine by Kärt Anvelt

- ↑ "Counterintelligence". Annual Review 2007 (PDF). Tallinn: Estonian Security Police. 2008. p. 8. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-04-15.

- ↑ KAPO aastaraamat 2007

- ↑ "Kaitsepolitsei aastaraamat: Vene luure tegi mullu Eestis usinalt tööd". Eesti Päevaleht (in Estonian). Retrieved 2023-08-22.

- ↑ Sullivan, Ruth (2003-02-24). "The". Financial Times. p. 32.

- 1 2 3 4 "Slim win for Estonia's left". CNN. 2003-03-02. Retrieved 2009-06-01.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Center-left party wins popular vote in Estonia". TheStar.com. 2003-03-03. Archived from the original on 2011-06-04. Retrieved 2009-06-01.

- ↑ Election leaves hung parliament, The Independent, 2003-03-03, p. 9

- ↑ Wines, Michael (2003-03-04). "World Briefing Europe: Estonia: Leftists Reeling After Election". The New York Times. Retrieved 2009-06-01.

- ↑ "The World This Week". The Economist. 2003-03-08. p. 8.

- ↑ Dieter Nohlen & Philip Stöver (2010) Elections in Europe: A data handbook, pp585–588 ISBN 978-3-8329-5609-7

- ↑ "Estonia: Two Parties Want To Form Government After Close Election". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. 2003-03-03. Archived from the original on 2009-02-17. Retrieved 2009-06-01.

- 1 2 "Estonia quandary after split vote". BBC News Online. 2003-03-03. Retrieved 2009-06-01.

- 1 2 "Estonia: parliamentary elections Riigikogu, 2003". Inter-Parliamentary Union. Retrieved 2009-06-01.

- ↑ "Koosmeele koalitsioon 2003 | Reformierakond" (in Estonian). 2022-03-30. Retrieved 2023-08-22.

- ↑ "Koosmeele koalitsioon". Arvamus (in Estonian). 2003-03-09. Retrieved 2023-08-22.

- ↑ "Res Publica pooldas koosmeele koalitsiooni". www.ohtuleht.ee (in Estonian). Retrieved 2023-08-22.

- ↑ "Res Publica pooldab koosmeele koalitsiooni". Delfi (in Estonian). Retrieved 2023-08-22.