Surface weather analysis of the storm on September 1, near peak intensity | |

| Meteorological history | |

|---|---|

| Formed | August 26, 1940 |

| Dissipated | September 3, 1940 |

| Category 2 hurricane | |

| 1-minute sustained (SSHWS/NWS) | |

| Highest winds | 110 mph (175 km/h) |

| Lowest pressure | 961 mbar (hPa); 28.38 inHg |

| Overall effects | |

| Fatalities | 7 |

| Damage | $4.05 million (1940 USD) |

| Areas affected | New England, Atlantic Canada |

| IBTrACS | |

Part of the 1940 Atlantic hurricane season | |

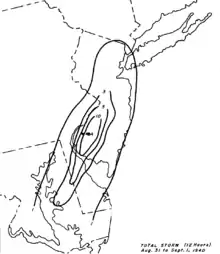

The 1940 New England hurricane moved off of the U.S. East Coast and Atlantic Canada in August and September 1940, producing strong winds and torrential rainfall. The fourth tropical cyclone and third hurricane of the season, the storm originated from a well-defined low-pressure area in the open Atlantic Ocean on August 26. Moving slowly in a general west-northwest motion, the disturbance intensified, reaching tropical storm strength on August 28 and subsequently hurricane intensity on August 30. The hurricane passed within 85 mi (137 km) of Cape Hatteras before recurving towards the northeast. The hurricane continued to intensify, and reached peak intensity as a Category 2 hurricane with maximum sustained winds of 110 mph (180 km/h) and a minimum barometric pressure of 961 mbar (hPa; 28.38 inHg), though these statistical peaks were achieved at different times on September 2. Afterwards, the hurricane began a weakening trend as it proceeded northeastward, and had degenerated into a tropical storm by the time it made its first landfall on Nova Scotia later that day. The storm transitioned into an extratropical cyclone the next day while making another landfall on New Brunswick. The extratropical remnants persisted into Quebec before merging with a larger extratropical system late on September 3.

Despite not making landfall on the United States, the hurricane caused widespread damage. Extensive precautionary measures were undertaken across the coast, particularly in New England. The heightened precautions were due in part to fears that effects from the storm would be similar to that of a devastating hurricane that struck the region two years prior. Most of the damage associated with the hurricane occurred in New Jersey, where the combination of moisture from the hurricane and a stationary front produced record rainfall, peaking at 24 in (610 mm) in the Ewan section of Harrison Township. This made the storm the wettest in state history. The resultant floods damaged infrastructure, mostly to road networks. Damage in the state amounted to $4 million.[nb 1] Farther north in New England, strong winds were reported, though damage remained minimal. Although the storm made two landfalls in Atlantic Canada, damage there too was minimal, and was limited to several boating incidents caused by strong waves. Overall, the hurricane caused seven fatalities.

Meteorological history

Tropical storm (39–73 mph, 63–118 km/h)

Category 1 (74–95 mph, 119–153 km/h)

Category 2 (96–110 mph, 154–177 km/h)

Category 3 (111–129 mph, 178–208 km/h)

Category 4 (130–156 mph, 209–251 km/h)

Category 5 (≥157 mph, ≥252 km/h)

Unknown

The origins of the hurricane can be traced to a compact and slow-moving low-pressure area in the open Atlantic Ocean in late August 1940. As the system progressed in a west-northwest direction, its center of circulation became more organized.[1] As a result, the disturbance was classified as a tropical depression between the Greater Antilles and Bermuda at 1200 UTC on August 26.[2] Operationally, the storm was analyzed to have undergone tropical cyclogenesis on August 30.[3] However, a reanalysis of the storm conducted in 2012 found that the system was already organized prior.[1][4] In its initial stages, the depression remained weak,[2] with few ships reporting abnormally strong winds in association with the storm.[1] Continuing in a slow west-northwest movement, the disturbance gradually intensified, and was analyzed to have attained tropical storm intensity by 1800 UTC on August 28.[2] At 0600 UTC on August 30, the tropical storm strengthened further into the equivalent of a modern-day Category 1 hurricane,[2] roughly 225 mi (362 km) east of the Florida peninsula.[3] At the same time, the hurricane began to intensify and move quicker than it had previously.[2] Later that day, a ship within the periphery of the storm reported winds of 60 mph (97 km/h) and a barometric pressure of 979 mbar (hPa; 28.90 inHg).[1][3]

At 1200 UTC on September 1, the hurricane attained modern-day Category 2 intensity. Ships continued to report strong winds and low pressures associated with the storm.[2] Early on September 1,[3] the hurricane passed 85 mi (137 km) of Cape Hatteras, North Carolina,[1] before recurving towards the northeast and away from the coast.[3] That same day, two ships reported hurricane-force winds. At 0200 UTC on September 2, the American steamboat Franklin K. Lane reported a barometric pressure of 965 mbar (965 hPa; 28.5 inHg) while located within the hurricane's radius of maximum wind;[1] this was the lowest pressure measured in association with the tropical cyclone and the lowest measured in the entire North Atlantic Ocean in September 1940.[5] Based on the ship observation, the storm was analyzed to have reached peak intensity on September 2 with maximum sustained winds of 105 mph (169 km/h) and a minimum central pressure of 961 mbar (961 hPa; 28.4 inHg). However, stronger winds of 110 mph (180 km/h) were analyzed to have been present in the hurricane earlier. As it traversed though more northerly latitudes, the storm began to gradually weaken.[2] The storm made landfall slightly northwest of Yarmouth, Nova Scotia at 2100 UTC later on September 2 as a tropical storm with winds of 70 mph (110 km/h).[1][3] After quickly passing over Nova Scotia, the weakening tropical storm transitioned into an extratropical storm over the Bay of Fundy at 0000 UTC on September 3.[2] At the same time, the cyclone made a second landfall on New Brunswick as a slightly weaker storm with winds of 65 mph (105 km/h). The extratropical system progressed over the Gulf of Saint Lawrence before it was absorbed by a larger extratropical storm at 1800 UTC later that day in Quebec just north of Anticosti Island.[1][3]

Preparations, impact, and aftermath

As the hurricane approached the United States East Coast on August 31, the United States Weather Bureau advised extreme caution to ships between Cape Hatteras and southern areas of New England.[6] Storm warnings were issued for coastal regions between Wilmington, North Carolina and the Virginia Capes. These warnings were later extended northward to the Delaware Breakwater. Strong winds exceeding gale-force were expected for much of the East Coast, particularly for Cape Hatteras.[7] On September 1, hurricane warnings were ordered for areas from Hatteras, North Carolina to Pamlico Sound, while previously issued storm warnings remained in place.[8] On September 2, gale warnings extended further north into Nantucket, Massachusetts.[9] In Norfolk, Virginia, city department heads were ordered to stand by for potential emergency duties. United States Coast Guard personnel were also dispatched along the North Carolina coast.[10] United States Navy personnel were detained in New London, Connecticut until the storm passed.[11] In Westhampton, New York, a mass evacuation occurred, involving 10,000 residences. Air traffic to and from Mitchel Air Force Base was cancelled, and 100 airplanes stationed at the base were fastened to the ground. Police and firemen evacuated a 50 mi (80 km) stretch of the Rhode Island coastline.[9] This included Roy Carpenter's Beach, where 1,000 families were forced to evacuate. In Narragansett Bay, boats were sent back to harbors or towed to shore.[12] The extensive precautionary measures undertaken occurred in part due to fears that the storm could cause similar effects to a destructive hurricane which swept through areas of New England two years prior.[9]

On September 1, the Venezuelan tanker Acosta relayed an SOS signal while near the hurricane 200 mi (320 km) southeast of the Frying Pan Shoals. United States Coast Guard stations in Norfolk, Virginia and Morehead City, North Carolina dispatched cutters to aid the ship.[8] Off of the East Coast, an offshoot of the hurricane resulted in the drownings of two people.[13] In the Mid-Atlantic states, the passing hurricane's outflow interacted with a cold front that had become quasi-stationary over the area. The cyclone's flow pattern enhanced the moisture environment over the region, resulting in locally heavy rainfall, particularly in New Jersey, where precipitation peaked at 24 in (610 mm) in Ewan in a nine-hour period on September 1.[14] This made the hurricane the wettest tropical cyclone in state history.[15] Most of the rain was in western portions of the state, however, with minimal rainfall at the coast.[14] The floods caused small rivers to overflow, breaching dams.[14] An overflowed creek inundated parts of Lumberton Township, rendering 2,000 people homeless. Rail service between Philadelphia, Pennsylvania and areas of southern New Jersey was suspended as a result of washed out tracks.[9] Resulting damage to infrastructure totaled $4,000,000 in the southwestern quarter of New Jersey alone. Damage to roads in Burlington County amounted to $2,500,000.[16] In Camden County, damage was estimated at $1 million.[13] Four fatalities were reported as a result of the floods.[17] In Delaware, rainfall was comparatively less.[14] However, rough seas generated by the hurricane offshore caused $50,000 in damages and one death.[9] Further north, strong gusts were reported across New England. Winds of 60 mph (97 km/h) were recorded by a weather station in Nantucket. Peak winds in Massachusetts were estimated at 65 mph (105 km/h). In Eastport, Maine, winds of 45 mph (72 km/h) were reported.[1]

After the storm, New Jersey state health department investigators from Trenton were dispatched to study the possibility for an increase in typhoid fever in flooded areas.[18] In Woodbury, where the city pumping station was flooded, water was rationed. Gas service was also limited in Woodbury, Pedricktown, Penns Grove. As a result of a gas plant becoming inundated in Glassboro, electricity was rationalized in Hammonton, forcing residents to eat uncooked food. Police were forced to transport residents of Mount Holly to work via boat due to the high floodwaters.[13]

Despite making two separate landfalls in Atlantic Canada on September 2 and September 3, the hurricane caused minimal damage. Effects in Nova Scotia were limited to boating incidents. In Lake Milo, near Yarmouth, six yachts capsized due to the strong winds. In New Brunswick, damage was also minimal. A car accident associated with the storm injured a man near Barnesville.[19]

See also

Notes

- ↑ All damage totals are in 1940 United States dollars unless otherwise noted.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Landsea, Chris; Atlantic Oceanic Meteorological Laboratory; et al. (December 2012). "Documentation of Atlantic Tropical Cyclones Changes in HURDAT". United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved May 2, 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Atlantic hurricane best track (HURDAT version 2)" (Database). United States National Hurricane Center. April 5, 2023. Retrieved January 10, 2024.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Gallenne, J.H. (September 1, 1940). "Tropical Disturbances of September 1940" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. 68 (9): 245–247. Bibcode:1940MWRv...68..245G. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1940)068<0245:TDOS>2.0.CO;2. Retrieved May 2, 2013.

- ↑ Atlantic Oceanography and Meteorological Laboratory's Hurricane Research Division. "The Atlantic Hurricane Database Re-analysis Project". United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved May 2, 2013.

- ↑ Hunter, H.C. (September 1, 1940). "Weather On The North Atlantic Ocean" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. Washington, D.C.: American Meteorological Society. 68 (9): 253–255. Bibcode:1940MWRv...68..253H. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1940)068<0253:WOTNAO>2.0.CO;2. Retrieved May 2, 2013.

- ↑ "Hurricane Off Coast of Carolina". The Evening Independent. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Associated Press. August 31, 1940. p. 1. Retrieved May 2, 2013.

- ↑ "Carolina Coast Menaced". The Evening Independent. Wilmington, North Carolina. Associated Press. August 31, 1940. p. 1. Retrieved May 2, 2013.

- 1 2 "Carolina Awaits Severe Hurricane". The Palm Beach Post. Manteo, North Carolina. Associated Press. September 1, 1940. p. 1. Retrieved August 31, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Storm Veers Away From New England". St. Petersburg Times. Associated Press. September 2, 1940. p. 1. Retrieved May 2, 2013.

- ↑ "Hurricane Near Carolina Coast". The Tuscaloosa News. Manteo, North Carolina. Associated Press. August 31, 1940. p. 1. Retrieved May 2, 2013.

- ↑ "Wilmington In Hurricane Path". The Sunday Morning Star. New York, New York. August 31, 1940. p. 6. Retrieved May 2, 2013.

- ↑ "Southern N.E. Sets Itself As Hurricane Nears". Meriden Record. Boston, Massachusetts. Associated Press. September 1, 1940. pp. 1–2. Retrieved May 2, 2013.

- 1 2 3 "New Jersey Fights To Prevent Disease". Daytona Beach Morning Journal. Camden, New Jersey. Associated Press. September 2, 1940. p. 1. Retrieved May 5, 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 Schoner, R.W.; Molansky, S.; Hydrologic Services Division (July 1956). "Rainfall Associated With Hurricanes (And Other Tropical Disturbances)" (PDF). Washington, D.C.: National Hurricane Research Project. pp. 262–263. Retrieved May 2, 2013.

- ↑ "Hurricanes and New Jersey". Hurricanes and the Middle Atlantic States. Archived from the original on 2013-07-06. Retrieved May 2, 2013.

- ↑ "Floods Inundate New Jersey Area". Ellensburg Daily Record. Camden, New Jersey. Associated Press. September 2, 1940. p. 1. Retrieved May 5, 2013.

- ↑ Souder, Mary O. (September 1, 1940). "Severe Local Storms" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. American Meteorological Society. 68 (9): 268. Bibcode:1940MWRv...68..268.. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1940)068<0268:SLS>2.0.CO;2. Retrieved May 2, 2013.

- ↑ "Hurricane Moves Seaward; New England Fears Relax". St. Petersburg Times. United Press. September 3, 1940. p. 8. Retrieved May 5, 2013.

- ↑ Environment Canada (November 12, 2009). "1940-4". Storm Impact Summaries. Government of Canada. Retrieved May 2, 2013.