On 3 June 1769, navigator Captain James Cook, naturalist Joseph Banks, astronomer Charles Green and naturalist Daniel Solander recorded the transit of Venus from the island of Tahiti during Cook's first voyage around the world.[1] During a transit, Venus appears as a small black disc travelling across the Sun. Transits of Venus occur in a pattern that repeats itself every 243 years, with two transits that are eight years apart, separated by breaks of 121.5 and 105.5 years.[2] These men, along with a crew of scientists, were commissioned by the Royal Society of London for the primary purpose of viewing the transit of Venus. Not only would their findings help expand scientific knowledge, it would help with navigation by accurately calculating the observer's longitude. At this time, longitude was difficult to determine and not always precise.[2] A "secret" mission that followed the transit included the exploration of the South Pacific to find the legendary Terra Australis Incognita or "unknown land of the South."[3]

Background

.jpg.webp)

In 1663, Scottish mathematician James Gregory came up with the idea of using Venus or Mercury transits to determine the astronomical unit by measuring the apparent solar parallax between different points on the surface of the Earth.[5] In a 1716 issue of the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, Edmund Halley illustrated Gregory's theory more fully and explained further how it could establish the distance between the Earth and the Sun. In his report, Halley suggested places that a full transit should be viewed due to a "cone of visibility". Places he recommended for observing the phenomenon included Hudson Bay, Norway and the Molucca Islands.[6] The next transits would occur in 1761 and 1769. Halley died in 1742, almost twenty years before the transit.[7]

The viewing of the 1761 transit involved the effort of 120 observers from nine nations.[7] Thomas Hornsby reported the observations as unsuccessful primarily due to poor weather conditions. He alerted the Royal Society in 1766 that preparations needed to begin for the 1769 transit.[8] Hornsby's publication in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society in 1766 focused attention on the "cone of visibility" indicating, like Halley, some of the better places to observe the transit.[8] The Royal Society boasted that the British "were inferior to no nation on earth, ancient or modern" and were eager to make another attempt.[9]

When choosing a location for viewing the transit, The Royal Society basically chose the locations Halley suggested in his 1716 article. The committee recommended that the transit be observed from three points: the North Cape at the Arctic tip of Norway, Fort Churchill at Hudson Bay Canada and a suitable island in the South Pacific. They stated that two competent observers were to be sent to each location. King George III approved of the project and arranged for the Navy to provide ships. He allocated £4,000 for the society to help with the expenses.[9]

Choosing an island, a ship and a Captain

In June 1767 British navigator Samuel Wallis made the first European contact with Tahiti. Wallis returned from his voyage in time to help the Royal Society decide that it would be an ideal location to observe the Transit of Venus. A big advantage was that Tahiti was one of the few islands in the South Pacific that they knew the longitude and latitude of. The Admiralty was not interested in specifically where in the South Pacific the observation of the Venus transit would take place. They were more interested in the "secret" mission that would be revealed after the Venus transit observation: the search for the alleged southern continent.[10] HM Bark Endeavour was chosen to take the astronomers and other scientists to Tahiti. James Cook was commissioned as Lieutenant and appointed to command the vessel.[11] Cook was considered the obvious choice as he was an outstanding seaman with navigational qualifications, a capable astronomer, and had observed a 1766 annular eclipse in Newfoundland that was communicated to the Royal Society by John Bevis.[12]

Preparation for the transit

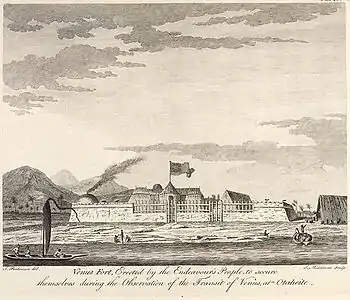

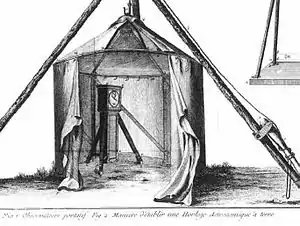

Once the Endeavour arrived on the island, Cook decided to set up the Venus transit observatory on shore. He required a completely stable platform which the ship could not provide and plenty of space to work with. The location of the observatory would be known as "Fort Venus." A sandy spit on the northeast end of Matavai Bay, named Point Venus by Cook, was chosen for the site.[13] They began building Fort Venus two days after they arrived. They marked a perimeter and construction began. It had earthworks on three of its sides adjacent to deep channels. Wood was gathered to construct palisades that topped the earthworks. Casks from the ship were filled with wet sand and used for stability. The east side of the fort faced the river. Mounted guns were brought in from the ship. A gateway was assembled and within this fortification, fifty-four tents were pitched which housed the crew, scientists, and officers as well as the observatory, blacksmith equipment and a kitchen.[14] Cook sent a party led by Zachary Hickes to a point on the east coast of the island for additional observations. John Gore led another group of thirty-eight more on a neighboring island of Eimeo (Mo’orea). Both parties were briefed and supplied with the needed equipment.[11]

The day of the transit

The observers were ordered to record the transit in four phases of Venus' journey across of the sun. The first phase was when Venus began "touching" the outside rim of the sun. In the second phase, Venus was completely within the sun's disc, but was still "touching" the outer rim. In the third phase, Venus has crossed the sun, was still completely within the disc, but was "touching" the opposite rim. Finally in the fourth phase, Venus was completely off the sun, but was still "touching" its outer rim.[2]

On the day of the transit, the sky was clear. Independent observations were made by James Cook, Green and Solander with their own telescopes.[1] Because of the rarity of the event, it was important to take accurate records. The next transit would not occur for more than a century, in 1874.[15]

In his journal, Cook wrote:

This day prov'd as favourable to our purpose as we could wish, not a Clowd was to be seen the whole day and the Air was perfectly clear, so that we had every advantage we could desire in Observing the whole of the passage of the Planet Venus over the Suns disk: we very distinctly saw an Atmosphere or dusky shade round the body of the Planet which very much disturbed the times of the Contacts particularly the two internal ones. Dr. Solander observed as well as Mr. Green and my self, and we differ'd from one another in observeing the times of the Contacts much more than could be expected. Mr Greens Telescope and mine were of the same Magnifying power but that of Dr was greater than ours.[16]

Recording the exact moment of the phases proved to be impossible due to a phenomenon called the "Black drop effect." Originally, it was believed that the effect came from the thick atmosphere on Venus, but the haziness was too extensive for this to be the reason. It is now believed that turbulence in the Earth's atmosphere leads to the smearing of the image of Venus.[17]

Results of the 1769 transit observations

The Royal Society was very disappointed in the results of data collected from the transit and Cook's report. The Tahiti observers had trouble with the timing of the stages and their drawings were inconsistent. They later found out that this was also true with the observers at the other locations. Observers from all over noted a haze or "black drop" that seemed to follow Venus making it very difficult to record time entry point on the sun and the exit from the sun.[2]

For what they believed to be a failure in the observation, The Royal Society decided to blame Green who died on the voyage back to England. Cook's rebuke was so sharp that it was struck from the official proceedings of the Society. Green was not given the opportunity to personally present his own data nor could he defend himself.[2]

Scientific community

Halley's 1716 article called for observers to witness the transit at various places on the globe. The response from the scientific community was astounding. There were at least 120 observers at sixty-two individual posts for the 1761 transit. Observations took place not only in Europe, but also included Calcutta, Tobolsk, Siberia, the Cape of Good Hope, and St. John's in Newfoundland.[18] The 1769 viewing also proved to be a vast international endeavor.[19]

Modern results compared to results from the 1769 transit

Using the solar parallax values obtained from the 1769 transit, the astronomer Thomas Hornsby wrote in Philosophical Transitions December 1771 that "the mean distance from the Earth to the Sun (is) 93,726,900 English miles." The radar-based value used today for the astronomical unit is 92,955,000 miles (149,597,000 km). This is only a difference of eight-tenths of one percent. Their work was within the bounds of the aphelion and perihelion distances to the sun, ~95 million miles and ~91 million miles respectively. These results have been described as "absolutely remarkable" considering what the astronomers had to work with.[19]

References

- 1 2 Rienits & Rienits 1976, p. 39.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Herdendorf 1986.

- ↑ Rienits & Rienits 1976, p. 28.

- ↑ London Missionary Society, ed. (1869). Fruits of Toil in the London Missionary Society. London: John Snow & Co. p. 12. Retrieved 12 September 2016.

- ↑ Teets 2003, pp. 335–348.

- ↑ Halley 1716.

- 1 2 Rice 2008.

- 1 2 Williams 2004.

- 1 2 Rienits & Rienits 1976, p. 24.

- ↑ MacLean 1974, p. 37.

- 1 2 Rienits & Rienits 1976, p. 25.

- ↑ Cook, J.; Bevis, J. (1767). "An Observation of an Eclipse of the Sun at the Island of New-Found-Land, August 5, 1766, by Mr. James Cook, with the Longitude of the Place of Observation Deduced from It: Communicated by J. Bevis, M. D. F. R. S." Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. 57: 215–216. Bibcode:1767RSPT...57..215C. doi:10.1098/rstl.1767.0025. ISSN 0261-0523.

- ↑ MacLean 1974, p. 54.

- ↑ MacLean 1974, p. 55.

- ↑ Teets 2003, p. 335.

- ↑ Beaglehole 1999.

- ↑ Pasachoff et al. 2004, p. 6.

- ↑ Teets 2003, p. 338.

- 1 2 Teets 2003, p. 347.

- Beaglehole, J.C., ed. (1999). The journals of Captain James Cook on his voyages of discovery (Reprint ed.). Rochester, NY: Boydell Press. pp. 182–183. ISBN 978-0-85115-744-3.

- Crosland, Maurice (22 January 2005). "Relationships between the Royal Society and the Academie des Sciences in the late eighteenth century". Notes and Records of the Royal Society. 59 (1): 30. doi:10.1098/rsnr.2004.0067. S2CID 71641646.

- Halley, Edmund (1716). "A New Method of Determining the Parallax of the Sun". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society. XXIX: 454. doi:10.1098/rstl.1714.0056.

- Herdendorf, Charles (January 1986). "Captain James Cook and the Transits of Mercury and Venus". Journal of Pacific History. 1. 21: 39–55. doi:10.1080/00223348608572527.

- MacLean, Alistair (1974). Captain Cook. London: Fontana. ISBN 978-0-00-653646-8.

- Pasachoff, Jay; Schneider, Glenn; Golub, Leon (2004). "The Black-Drop Effect Explained". Proceedings IAU Colloquium. 196.

- Rice, Tony (2008). Voyages of discovery : a visual celebration of ten of the greatest natural history expeditions. Richmond Hill, Ont.: Firefly Books. ISBN 978-1-55407-414-3.

- Rienits, Rex; Rienits, Thea (1976). The voyages of Captain Cook. London: Hamlyn. ISBN 978-0-600-04111-5.

- Teets, Donald (December 2003). "Transits of Venus and the Astronomical Unit" (PDF). Mathematics Magazine. 76 (5): 335–348. doi:10.1080/0025570X.2003.11953207. S2CID 54867823.

- Williams, Glyndwr, ed. (2004). Captain Cook : explorations and reassessments (first ed.). Rochester, N.Y.: Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1-84383-100-6.