What are the psychological causes of road rage behaviour and how can road rage be prevented?

Overview

Motor-vehicle accidents are the leading cause of death for those aged 18 to 24 years in the United States (Bumgarner, Webb & Dula, 2016). The leading cause of traffic fatalities is aggressive driving, with reports of over 50% of fatalities occurring as a result of this behaviour (Bushman, Steffgen, Kerwin, Whitlock & Weisenberger, 2018). Driving anger is a significant predictor of aggressive driving, driving errors and risky driving whilst also being linked to an increased risk of accident involvement (Zhang & Chan, 2016). Each of these variables are what constitute road rage, alongside verbal or physical abuse towards other drivers. Road rage is highly prevalent, with reports of up to 90% of the population being victimised by some form of road rage (Pfeiffer, Pueschel & Seifert 2016). As such, in order for safer roads and a minimisation of harm, the underlying psychological causes of road rage requires investigation and preventive strategies need to take place on a grander scheme.

- Focus questions

- What is road rage and what behaviours represent it?

- What thoughts and behaviours are behind road rage?

- How do situational and social factors shape the development of road rage?

- What are the best treatments for road rage?

Types of road rage behaviour

Road rage encompasses a number of different behaviours that are targeted at other drivers or pedestrians in an effort to release frustration or intimidate. These can include:

- Aggressive driving - e.g. tailgating, aberrant overtaking, swerving, excessive honking.

- Risky driving and driving errors prompted emotionally

- Violence and murder

- Verbal abuse or rude/offensive gestures (see Figure 1)

At the height of road rage, small conflicts can potentially escalate to life-threatening assault. A key issue with the road rage scenario is that the vehicle itself is a means for expressing anger, and can readily be used for violent intent. A report by Pfeiffer, Pueschel & Seifert (2016) compiled 116 cases of interpersonal violence from road rage incidents. The most common triggering event was traffic route utilisation (for instance, conflict of route between cyclists and motorists). 12% of cases were also without any apparent reason, which brings into question the role of mood and general anger being channelled through road rage. In 79 cases, only physical violence was used, whereas 36 cases involved instruments - the main type being the vehicle itself. In 9 cases there were life-threatening injuries. Close to 90% of the cases involved no prior relationship between the perpetrator and the victim. This highlights the extent to which insignificant one-off events on the road are blown out of proportion through a road rage mentality. |

Causes of road rage

There are many causes of road rage, ranging from specific triggers to an overall attitude of aggression or cognitive biases whilst driving. These can be broken down into person-related factors and situational and social factors. Person-related factors include links to illusion of control (Stephens & Ohtsuka, 2014) and superiority (Măirean & Havârneanu, 2018), rumination in relation to road rage (Suhr & Nesbit, 2013), personality disorders such as intermittent explosive disorder (American Psychiatric Association, 2013), and age, gender and experience (Wu, Wang, Peng & Chen, 2018). Situational and social factors include theoretical frameworks such as the frustration-aggression hypothesis (Zhang & Chan, 2016) and social learning theory (Bandura, 1977), as well as triggering events from other drivers and environmental circumstances (Sagar, Mehta & Chugh, 2013; Peng, Wang & Chen, 2019).

Person-related factors

- Pre-existing cognitive biases play a large part in how driving aggression is enacted (Stephens & Ohtsuka, 2014; Măirean & Havârneanu, 2018). Current circumstances on the road may be assessed poorly due to being subject to the mood of the individual, where anger already established may interfere with events and decisions on the road and be taken out of proportion (Stephens, Koppel, Young, Chambers & Hassed, 2018). In addition, an illusion of control can interfere with how a driver perceives a situation, and in turn how they react to the event. For instance, Stephens & Ohtsuka (2014) used self-report data of 220 licensed drivers, measuring their feelings of control during driving and their driving behaviour. It was found that a significant effect existed between drivers with higher perceived control during driving and aggressive driving. This reflects how certain events on the road can contradict a driver’s cognitive biases or amplify their pre-existing mood and potentially lead to road rage or aggressive countermeasures.

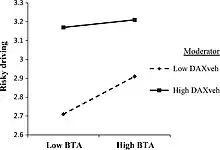

- Recent research by Măirean & Havârneanu (2018) investigated the relationship between illusion of superiority, driver aggressiveness, and risky driving behaviour. Results showed that a ‘better than average’ (BTA) effect was significantly positively associated with both aggressive driving and risky driving behaviour. The use of the vehicle to express anger also moderated this interaction, but only for lower levels of this behaviour (see Figure 2). This moderator effect highlights an important implication in regards to how even lower aggressive driver’s may feel urged into aggressive and risky driving behaviour due to their perceived superiority.

- Another study looked at the relationship between levels of narcissism and aggressive driving (Bushman, Steffgen, Kerwin, Whitlock & Weisenberger, 2018). The hypothesis centres on the idea that narcissists believe they deserve treatment, and when this isn’t given to them, they lash out in an aggressive manner. Several measures of road rage and aggressive driving confirmed this thinking, where narcissism was positively related on all accounts. Overall, whether it’s through a narcissistic personality or being overly confident in one’s driving abilities, there is a distinct link between perceived superiority and road rage.

- Another important cognitive link to road rage is in the form of rumination (Suhr & Nesbit, 2013). Rumination is a style of thinking where negative thoughts of distress from a problem are passively focused on, rather than problem solving or coping strategies. Two studies by Suhr & Nesbit (2013) emphasised the role this mode of thinking had on road rage. The first study confirmed a significant association with ruminative-response styles and histories of aggressive driving behaviours in participants. The second study utilised an experiment to manipulate participants to either ruminate or be distracted during a driving-related task. Similarly, a link was established in this study whereby those who were instructed to ruminate had higher aggressiveness.

- One of the causes related to road rage incidents is sourced from mental disorders, and in particular, intermittent-explosive disorder (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) characterises the diagnosis of this disorder based on regular impulse-based outbursts of verbal or physical aggression, being severely out of proportion to the provocation or triggering event. As such, disorders involving problems with impulse control such as this can also play a large part in road rage incidents.

- In general, findings on age, gender and experience have also indicated an influence on road rage incidence. 1400 questionnaires in China were completed in relation to how certain driving acts induced road rage and aggression (Wu, Wang, Peng & Chen, 2018). The findings showed that a strong effect existed for gender, where males show more road rage behaviour in almost all situations described on the questionnaire. In addition, younger people and less experienced drivers also showed significant effects in some areas of the questionnaire, where certain aggressive driving behaviour was less likely for these groups.

Situational and social factors

- A popular explanation for the mechanisms behind anger is the frustration-aggression hypothesis. This idea is based on situational factors that prevent one from reaching certain goals, and in turn leads to expression of anger. The two main goals for drivers are to achieve their destination on time and drive safely (Zhang & Chan, 2016). When these goals are blocked, road rage can take form. Furthermore, due to situational factors such as being able to use the vehicle to express aggression, anonymity on both sides, and the pressure to meet driving goals, the chance of outward expression of anger is more likely.

- The exact events on the road also give light to a pattern of road rage responses. For instance, research conducted by Peng, Wang & Chen in 2019 analysed cases of road rage caused by aberrant overtaking. It was found that this behaviour was often a trigger for the development of road rage in both parties involved, where stimulation from verbal abuse was the largest predictor of accidents and incidents of harm. A study on Indian drivers also found similar results with overtaking, whilst identifying other triggers such as excessive honking, tailgating and playing loud music (Sagar, Mehta & Chugh, 2013). It is important to note that both these studies support the fact that road rage itself is a trigger for further road rage and that this reciprocates quickly, and often severely, in many incidents.

- Environmental and climate factors have been found to increase likelihood of road rage. Hot and humid weather has been shown to significantly increase anger on the road. This is due to furthering frustration and creating an added stressor for completing travel (Sagar, Mehta & Chugh, 2013). In addition, traffic congestion and loud noise is directly related to road rage and amplifies this effect (Sagar, Mehta & Chugh, 2013). This is due to creating a circumstance of feeling trapped in an uncomfortable, stressful environment.

- Another way in which the development of road rage behaviour can occur is through processes outlined in Albert Bandura’s social learning theory (1977). The basis of social learning theory is that new behaviours can be learned through observation and imitation of models. In this case, a prime example would be children learning road rage behaviour from their parents or other key models during travel. Vicarious reinforcement could also be prone to this situation as the consequences of the model’s actions may not be punished due to their beliefs of superiority or having the right to behave aggressively. The anonymity of the model's actions on the road can also be learned through this same reinforcement. The consequences may be learned over time which in turn increases the likelihood that road rage behaviour may be imitated and accepted as being normal and even healthy.

What makes the perfect situation for road rage? Studies have shown specific environmental factors like the weather, traffic congestion and noise play an important part in road rage statistics (Sagar, Mehta & Chugh, 2013). Certain times and periods of the year may also be risk factors. Looking at thousands of Instagram posts in US states using #roadrage, statistics show that the term was most commonly used in August, with 6pm being the most frequent time, and Friday’s being the most frequent day (Bayly, 2016). This reflects a period of time where commuters are either on holiday or looking to get home for the weekend. Traffic congestion is at a peak during these times as well, with summer weather and holiday alcohol consumption may also potential variables. California had the most frequent rates of #roadrage usage, being the state home to the largest amount of traffic congestion within the nation. |

Prevention of road rage

The prevention of road rage can be given through eliminating the source problems directing the behaviour. However, there are also multiple exercises and therapies that can be used for general cases of road rage. These can be broken down into strategies of meditation and relaxation, and cognitive-behavioural based prevention. These treatments are often combined and interrelated as they target the same symptoms and have the same goal of managing anger and aggressive thoughts and behaviours (Deffenbacher, 2016). They include relaxation interventions, mindfulness training, breath control and cognitive and/or behavioural therapy.

Meditation and relaxation

- Relaxation interventions are a key treatment for road rage. Clients are generally taught tension-release exercises of progressive relaxation to use during high anger situations while driving (Deffenbacher, 2016). For example, certain muscle groups can be focused on for systematic relaxation, where other methods such as cue-controlled relaxation through paired words and imagery can also be taught. One of the training formats for relaxation is through visualisation with a therapist, where imaginary scenarios are acted out starting from moderate intensities and are then increased over time as coping skills develop (Deffenbacher, 2016). This enables transition into real-life scenarios where the same exercises and patterns of thoughts can be applied. Systematic reviews of this treatment confirm efficacy in numerous facets across a number of studies (Deffenbacher, 2016). Effects from the analysis include lowered driving anger, aggressive driving, risky driving, and general anger. Furthermore, studies with cognitive measures found that relaxation reduced aggressive and hostile thinking.

- Mindfulness is a meta-cognitive practice with the direction having non-judgemental thought to only the current moment, as well as any emotional and physical states or reactions (See Figure 3). Its purpose to alleviate negative emotional reaction through changing the way in which situations or triggers are evaluated. In the case of road rage, this prevention method looks at the underlying cause as being a negative cognitive bias, where rumination and other maladaptive cognitive processes are targeted. Stephens, Koppel, Young, Chambers & Hassed (2018) investigated the impact of mindfulness on driving anger and aggressive driving. Similar to past research on anger outside of a driving context, a significant negative relationship was found for mindfulness for both driving anger and aggressive driving. Further analysis showed that mindfulness only related to driving anger, which subsequently influenced aggressive driving. As such, training drivers that are prone to driving anger using mindfulness may help reduce aggressive driving and change the way they evaluate their decision making on the road.

Figure 3. Meditation often incorporates mindfulness.

Figure 3. Meditation often incorporates mindfulness. - Breath control has been a technique associated with number of different benefits to psychophysiological outcomes such as reduced anger, stress and arousal, and heightened relaxation, pleasantness, and alertness (Zaccaro et al., 2018). In this case, voluntary slow breathing has shown these effects, where it is hypothesised that it is directly related to internal body states and activity of the brain (Zaccaro et al., 2018). Slow-breathing can therefore be used as a preventative countermeasure to anger, stress and triggers experienced whilst driving. This technique can be trained for drivers prone to road rage breakdowns for when they’re experiencing the onset or moment of anger. In contrast, one study looked at a fast breathing intervention for drivers where interventions to boost energy and alleviate drowsiness were the focus (Balters, Murnane, Landay & Paredes, 2018). It was found that this method had reports of road rage in certain traffic situations, such as traffic congestion. This shows the polarity of use for breath control and further reinforces slow breathing as the means for countering road rage symptoms.

Cognitive-behavioural based prevention

- Cognitive based treatment for road rage deals with managing the thoughts behind provoking stimuli whilst driving. Fixing harmful interpretations and re-framing negative perspectives is the goal of cognitive interventions for road rage. The basis of treatment is for clients to become aware of the anger enhancing themes in their cognitive processes. Treatment generally targets these processes such as catastrophising, overgeneralising, labelling, demanding, revenge thoughts, hostile attributional bias, and beliefs that support aggression (Deffenbacher, 2016). Studies on cognitive treatment for angry drivers found improvement with less driving anger, aggressive driving, risky driving and hostile thinking being observed post-treatment and at one-month and one-year follow ups (Deffenbacher, 2016). In summary, cognitive treatment builds upon positive coping to counteract road rage. Being accepting, less demanding, and more forgiving are elements focused on as well as striving to redirect attention and take control of oneself rather than uncontrollable circumstances on the road.

- The behavioural component of road rage takes form in aggressive driving where it is easy for the individual to channel their expression of anger through using their vehicle. In addition to cognitive-based strategies, there are a number of behavioural techniques to help manage aggressive driving. Examples of behavioural coping skills included avoiding anger triggers, being patient or taking a time out, adapting distractions, and focusing on problem solving and safety behaviours (Zinzow & Jeffirs, 2017). Experiments on behavioural interventions using coping mechanisms such as these have displayed strong effectiveness, with aggressive driving having an average improvement of 50% when compared to control groups (Zinzow & Jeffirs, 2017). Although the methods are efficient standalone, they are also most often integrated with cognitive and relaxation-based techniques, where cognitive behavioural therapy is the most prominent choice for treatment (Deffenbacher, 2016).

Conclusion

The key issue with road rage is eliminating aggressive driving due to the prevalent outward harm and cost it has to society. The role of detrimental cognitive processes is a largely established cause for road rage behaviour and is what can bring the full extent of anger expression out in otherwise normal individuals. Interventions for road rage are therefore best when targeting the source problem of the behaviour itself, being the formation of the emotional reaction and the cognitive mechanisms behind making aggressive decisions in the first place. In addition, an awareness of social and situational factors is required to prevent potential triggers or imitations of harmful behaviours. In order to strengthen the effect of managing ones thoughts, other techniques such as relaxation, mindfulness and breath control can help maintain states that counteract the development of anger or aggressive driving. At the end of the day, only the individual is responsible for letting themselves get carried away - one must accept and predict frustrations and only focus on their driving. The importance of keeping a realistic perspective is vital so that individuals don't let minor events or ill-made decisions turn into harmful scenarios.

See also

- Aggression (Book chapter, 2013)

- Intermittent explosive disorder (Wikipedia)

- Narcissism (Book chapter, 2010)

- Mindfulness (Book chapter, 2013)

- Road rage (Wikipedia)

- Rage (Wikipedia)

- Violent crime motivation (Book chapter, 2010)

References

Balters, S., Murnane, E., Landay, J., & Paredes, P. (2018). Breath booster!: Exploring in-car, fast-paced breathing interventions to enhance driver arousal state, in proceedings of the 12th EAI International Conference on Pervasive Computing Technologies for Healthcare (PervasiveHealth '18). ACM, New York, NY, USA, 128-137. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1145/3240925.3240939

Bandura, A. (1977). Social learning theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Bayly, L. (2016). Want to Avoid the Summer's Worst Road Rage? Don't Drive at This Time. Retrieved 20 October 2019, from https://www.nbcnews.com/business/business-news/want-avoid-summer-s-worst-road-rage-don-t-drive-n571226

Bumgarner, D., Webb, J., & Dula, C. (2016). Forgiveness and adverse driving outcomes within the past five years: Driving anger, driving anger expression, and aggressive driving behaviors as mediators. Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology And Behaviour, 42, 317-331. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trf.2016.07.017

Bushman, B., Steffgen, G., Kerwin, T., Whitlock, T., & Weisenberger, J. (2018). “Don’t you know I own the road?” The link between narcissism and aggressive driving. Transportation Research Part F: Psychology and Behaviour, 52, 14–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trf.2017.10.008

Deffenbacher, J. (2016). A review of interventions for the reduction of driving anger. Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology And Behaviour, 42, 411-421. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trf.2015.10.024

Măirean, C., & Havârneanu, C. (2018). The relationship between drivers’ illusion of superiority, aggressive driving, and self-reported risky driving behaviors. Transportation Research Part F: Psychology and Behaviour, 55, 167–174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trf.2018.02.037

Peng, Z., Wang, Y., & Chen, Q. (2019). The generation and development of road rage incidents caused by aberrant overtaking: An analysis of cases in China. Transportation Research Part F: Psychology and Behaviour, 60, 606–619. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trf.2018.12.002

Pfeiffer, J., Pueschel, K., & Seifert, D. (2016). Interpersonal violence in road rage. Cases from the Medico-Legal Center for Victims of Violence in Hamburg. Journal of Forensic and Legal Medicine, 39, 42–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jflm.2015.11.023

Sagar, R., Mehta, M., & Chugh, G. (2013). Road rage: An exploratory study on aggressive driving experience on Indian roads. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 59(4), 407–412. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764011431547

Scott-Parker, B., Jones, C., Rune, K., & Tucker, J. (2018). A qualitative exploration of driving stress and driving discourtesy. Accident Analysis and Prevention, 118, 38–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aap.2018.03.009

Stephens, A., & Ohtsuka, K. (2014). Cognitive biases in aggressive drivers: Does illusion of control drive us off the road? Personality and Individual Differences, 68, 124–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2014.04.016

Stephens, A., Koppel, S., Young, K., Chambers, R., & Hassed, C. (2018). Associations between self-reported mindfulness, driving anger and aggressive driving. Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology And Behaviour, 56, 149-155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trf.2018.04.011

Suhr, K., & Nesbit, S. (2013). Dwelling on “Road Rage”: The effects of trait rumination on aggressive driving. Transportation Research Part F: Psychology and Behaviour, 21, 207–218. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trf.2013.10.001

Wu, X., Wang, Y., Peng, Z., & Chen, Q. (2018). A questionnaire survey on road rage and anger-provoking situations in China. Accident Analysis and Prevention, 111, 210–221. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aap.2017.12.003

Zaccaro, A., Piarulli, A., Laurino, M., Garbella, E., Menicucci, D., Neri, B., & Gemignani, A. (2018). How Breath-Control Can Change Your Life: A Systematic Review on Psycho-Physiological Correlates of Slow Breathing. Frontiers In Human Neuroscience, 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2018.00353

Zhang, T., & Chan, A. (2016). The association between driving anger and driving outcomes: A meta-analysis of evidence from the past twenty years. Accident Analysis and Prevention, 90, 50–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aap.2016.02.009

External links

- Dealing with road rage (Anger Management Resource)

- Road rage test (monkeymeter.com)