What is impulsivity, what are its consequences, and what can be done about it?

Overview

This book chapter explains impulsivity, theories, the brain regions responsible for impulsivity, risk factors and treatments of impulsive behaviours. The human brain is a complex organ, which regulates how people react to different situations. Many studies have been conducted on the brain to explain how individual human beings come to a particular solution when exposed to certain environmental characteristics. For instance, during an emergency, while some people might stay calm and figure out what to do to restore calmness, while others act on a whim and end up with positive or negative consequences. This chapter discusses how the existing studies maintain about impulsivity and the effects of being impulsive. By examining the brain structures involved with impulsivity coupled with theories which help explain mechanisms responsible for self-control and self-regulation and how they develop over time, we can start to unravel the motivational influences which lead to impulsive behaviour which more often than not develops into anti-social tendencies if left unchecked. By the end of this book chapter, you will be able to understand why some individuals are more impulsive than others and how impulsivity may be modified to assist an impulsive person to develop self-control and self-regulation.

What is Impulsivity?

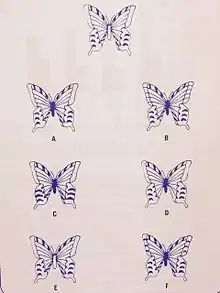

Let's begin with a quick test. Looking at Figure 1, which of the six butterflies is the identical match for the one on top?

Did you find that your eyes scanned straight to the matching butterfly? Or did you meticulously check each one before making your decision? If you chose before looking at all the butterflies carefully, you may be an impulsive thinker. The faster your response, the more likely you are to make mistakes. This example of a Matching Familiar Families Test (MFF) (Kagan, 1966) demonstrates how impulsive individuals operate. Impulsivity is a stable disposition, characterised by a lack of foresight, problems with delaying gratification, and inhibiting inappropriate responses (Patton, Stanford, & Barratt, 1995). Impulsivity refers to a tendency to respond to a situation with little or no forethought calculating, reflecting or considering the consequences of the response (Hollander, & Berlin, 2008). Impulsivity is also known as acting on a whim. Impulsivity often leads to undesirable results because of failure to think appropriately, what is the most suitable solution or action to adopt when placed in certain circumstances. Acting on a whim is a multifactorial construct in the sense that certain impulsive reactions lead to desirable results. In case an impulsive action leads to a beneficial effect, the person said to be courageous, bold, a quick thinker and much more (Reeve, 2015). Therefore, impulsivity has two components, which include response without much forethought, which may or may not be fruitful and deliberately choosing short-term advantage without considering future or long-term gains.

Theories

An understanding of the following theories allows individuals to gain a more in depth level of knowledge, specifically why these theories are important and what they aim to address within the context of impulsivity. Lastly, these theories provide an explanation to what they are responsible for.

Self Control TheorySelf-control is the degree to which a person can restrain, control or tone down an impulsive urge to do something, which has short-term gains but instead focuses on achieving a long-term goal (Reeve, 2015). Parental socialisation mainly influences self-control since childhood. Parents who are capable of changing their children's gratification urge determine how in future the child will behave. Poor parenting causes children to find it hard to delay gratification hence look for shortcuts to survive in life. Self-control influences criminal behaviour in the sense that lack of self-control leads to criminal acts such as stealing, robbing, and harming others. Individuals parented inappropriately before the age of ten are more likely to show less self-control compared to individuals who receive good parentage (Reeve, 2015). Desire is a motivation to achieve a result, which will bring about relief. A desire turns into temptation if it tempers with one's self-control. All human beings have desires but what makes people different is how they respond to those desires. For instance, everyone wants to be comfortable in life and afford whatever they want such as big houses, a good family and much more (Muraven et al., 2006). Desires cause temptations, and people who have low self-control are more likely to succumb to the temptations and end up acting impulsively. For example, an employee might impulsively steal from the employer without putting into consideration the consequences of theft because they have low or do not have the willpower to resist the desire to achieve individual goals in life. Dual Process ConceptDual process theory explains how a thought can occur in two varied ways or from two processes. Thoughts often arise from implicit or explicit processes. The implicit process is the automatic response to something, whereas the explicit process is the controlled or conscious way of thinking (Reeve, 2015). Explicit processes are easily changeable through persuasion or learning new concepts because they are controlled consciously. However, implicit processes, may be referred to as attitudes are not easy to alter. The prefrontal cortex (PFC) and orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) are brain parts responsible for self-control and resistance of temptations. On the other hand, the subcortical brain part controls basic urges in the body such as thirst and sex drive (Reeve, 2015). The reason for differences amongst human beings' impulsivity is due to the biological structure of their brains and the way their brain functions. Impulsivity is regulated by the activity of the brain either in the right or left PFC hemisphere (Hollander, & Berlin, 2008). If an individual's cortical brain structures are mature, then the ability to control basic motivational urges will be higher. The motivational urges which take place in the subcortical brain are the ones which arise as impulsive behaviour because the inability to control them causes a person to think and act impulsively. During the thinking and planning processes, people whose left prefrontal lobes are sensitive are more likely to be optimistic and motivated. A left prefrontal lobe which is sensitive and active sensitises the Behavioural Activation System (BAS) which is responsible for human motivation (Smillie, Dalgleish, & Jackson, 2007). Ego Depletion ConceptEgo depletion refers to a concept derived from the psychological theory of self-control (Hagger, Wood, Stiff, & Chatzisarantis, 2010). The self-control of self-regulation theory maintains that willpower works similarly to muscles. According to studies, human tasks that require self-control can cause this muscle to become weak and result in ego depletion which in turn reduces a person’s ability to practice restraint or self-control. Several researchers have also performed lab experiments on ego depletion such as experimenting suppression of emotions and thoughts on how the brain can make a large number of different difficult decisions. According to Baumeister et al., (2008), ego depletion causes people to arrive at less reasonable choices. Other researchers such as Hagger & Chatzisarantis (2016) opine that the resource depletion self-control model's evidence is now being overestimated. Ego depletion decreases a person's willingness to participate in normal activities such as decision making, controlling the environment, and beginning an action. However, the reason for ego-depletion is not due to performing a difficult task, but because of taking part in self-control tasks (Baumeister, Galliot, DeWall, & Oaten, 2006). Difficult tasks such as memorising new concepts and solving complex math's problems do not cause ego-depletion because they don't need self-control to be performed. During the radish experiment, the participants stayed for three hours without taking a meal before they were instructed to enter into a room full of freshly baked cookies' smell. All the participants offered radishes and cookies. The control group was requested to take the cookies while the experimental team was asked to take the radishes. After five minutes all the participants took part in an impossible geometric task to test their energy levels. The participants who ate the cookies showed more resilience than those who ate radishes. Those who ate cookies persisted for approximately 19 minutes before giving up. Instead, the group which ate radishes only lasted for an average of 8 minutes before giving up on the task (Hagger, Wood, Stiff, & Chatzisarantis, 2010). The reason for the difference in persistence was due to energy levels. Those who ate cookies had more energy hence were able to persist with the task. The brain becomes more impulsive after getting exhausted as it lacks the energy necessary for functioning soundly (Baumeister & Teirney, 2012). It is essential to replenish the brain by use of substances such as glucose, which energize the brain and do away with impulsivity (Hagger, Wood, Stiff, & Chatzisarantiset, 2010). Because the primary characteristic of impulsivity is the inability to do away with wanting short-term gains at the expense of the long-term ones, impulsive people are more likely to experience ego-depletion (Baumeister et al., 2006). |

Brain Structures

The two main brain structures responsible for impulsivity are the prefrontal cortex and the orbitofrontal cortex. As you read on you will gain a broader understanding into the roles of each specific brain region and how it relates to impulsivity. {{Robelbox|theme=

|

Prefrontal Cortex: _animation.gif) Figure 2. Prefrontal cortex, part of the cortical brain, is associated with making plans, setting goals and go/no-go responses. The prefrontal cortex (PFC) is the frontal lobe's cover found in the outer cortical brain- the cerebrum. The PFC is responsible for thinking, moderating social behaviour, and planning. The PFC consist of two lobes or hemispheres - the right PFC and left PFC - and lies immediately behind the forehead. Together, the two lobes are responsible for many important motivations including affect, goals and personal strivings (Reeve, 2015). The right hemisphere tends to produce negative emotion and no-go avoidance motivation whereas the left hemisphere produces positive emotion and go approach motivation. For example, when thoughts, intentions, goals and strivings stimulate the left hemisphere, a person is likely to generate positive thoughts and approach-oriented feelings. The human PFC is the largest and most evolved of all the primates and continues to develop from infancy right through adolescence and into early adulthood (Hollander & Berlin, 2008). Therefore, its capacity to make complex decisions regarding goals and rewards (as well as the ability put the brakes on behaviour that may lead to adverse outcomes) start off relatively weak during early childhood but grow in strength as the individual matures. |

Orbitofrontal cortex: Figure 3. Orbitofrontal Precortex: A major function is inhibiting inappropriate actions, central to the ability to delay gratification. Orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) is located at the base of the PFC and the area is responsible for storing and processing reward-related information that helps people evaluate their preferences and choices for objects such as which product to buy (See Figure 4). It guides our behaviour regarding incentive value but it also inhibits inappropriate behaviour. The OFC is central to the ability to delay gratification which is a very important role because most long-term plans, such as working toward an HD-quality motivation book chapter, involve the ability to put aside short-term impulses such as checking Facebook, calling friends or going for a swim (Hollander & Berlin, 2008). The OFC in humans resulted in the preferential response to small rewards over delayed, efficient rewards. Research has also uncovered that deficits in dopamine pathways within the OFC resulted in disinibition, socially inappropriate behaviour and impulsivity (Hollander & Berlin, 2008) In one study, (Berlin, Rolls, & Iversen, 2005) patients with Parkinson's Disease were treated with dopamine enhancing medication and found that their overt impulsively as measured through self-report and self-control tasks reduced significantly. The OFC plays a major part in addictive behaviour just like the nucleus accumbens and amygdala. The OFC's striato-thalamo-orbitofrontal circuit leads to the formation of addictive behaviours as it activates dopamine. Due to this, it leads to a compulsive and repetitive act of doing something (Schultz, Tremblay, 2006). The disruption of striato-thalamo-orbitofrontal circuit in drug-dependent individuals increases the urge to continue using those drugs no matter the consequences. Individuals with addiction problems have been found to have issues with orbitofrontal, striatal, and thalamic parts of the brain (Bandy & Moore, 2010). |

Behavioural Activation System (BAS) and Impulsivity

Jeffrey Allan Gray is the proponent of the Reinforcement Sensitivity Theory (RST) which has two features, Behavioral Inhibition System and Behavioral Activation System (Reeve, 2015). These two systems are opposite to each other. The RST model maintains that human behaviour is due to individual differences in how people are sensitive to reward and punishment. The level of sensitivity to reward and punishment by human beings causes either positive or negative reinforcement towards a particular stimulus such as drugs (Lopez et al., 2012). The Behavioural Activation System influences the sensitivity of an individual to reward and motivation. BIS is considered to be linked with anxiety while BAS is directly associated with the trait of impulsivity (Smillie et al., 2007).

The BAS activates appetitive motivation hence causes individuals to be determined to achieve goals. Availability of rewards arouses the BAS and availability of punishment repulses it. Therefore, it selectively deals with rewards with no regard to punishment. Individuals with higher BAS levels display more positive emotions such as happiness and high hopes when presented with non-punishment and rewarding situations (Lopez et al., 2012). Additionally, high BAS levels cause individuals to be attracted to goal-oriented activities and experiences when presented with awards. The BAS directly connects with catecholaminergic and dopaminergic brain pathways, which elicit positive emotions. These positive feelings are the cause of high probability of elation and happiness in case a person attains a goal. Individuals with high levels of BAS learn better when taught through the presentation of rewards as opposed to punishment.

Experimental research has indicated that higher levels of urge to take alcohol by alcohol users is due to BAS sensitivity or high trait of impulsivity (Kambouropoulos & Staiger, 2004b). High and low rates of impulsivity depend on several neurological factors which influence the parts of the brain responsible for sensitivity to rewards after achieving a particular goal. These varied levels of impulsivity lead to individual differences and behaviour. Behaviours encouraged or influenced by rewards a normally addictive because they become impulsive and challenging to control urges (Smillie et al., 2007).

Executive Function

The executive function and self-regulation skills are instrumental in planning, attention, memory, and multi-tasking (Scope, Epson, & McHale, 2010). Humans need to make deliberations on what is the best thing to do at any time; it needs to set goals and look at ways of achieving them, and control impulsive urges or delay gratification. The executive function comprises of cognitive processes vital for behaviour control, selection of goals and behaviour control to enhance goal achievement. It also includes control of attention, cognitive inhibition, thinking flexibility, and working memory. Moreover, the executive function is involved in problem solving and reasoning (Scope, Epson, & McHale, 2010).

The human executive functioning develops with progression in age. Children have a low executive functioning because their brain has not developed cognitively. However, an individual's cognitive processes are influenced by the life events one passes through (Yuan, Peng & Naftali, 2014). During childhood, children use the working memory and inhibitory control which are features of the executive function. At the age of about 5 years, children develop in terms of cognitive flexibility, goal-oriented behaviours as they learn about planning. Their executive functioning is not well developed at this stage of life because they are not aware of when to use given strategies in a particular situation.

During adolescent period is when integration of different brain systems occurs. Executive functioning improves tremendously at this stage in addition to planning and goal-setting. Attention control and working memory also improve at this age. At adulthood the major brain change is constant myelination of neurons located in the PFC (Yuan, Peng & Naftali, 2014). The executive function attains its peak in the period between 20 to 29 years and that is why during this period individuals can participate in mentally challenging tasks and solve them. At advanced old age the executive function starts declining and cognitive skills decline due to wear out of the cells (Scope, Epson, & McHale, 2010). |}

Quiz

To help consolidate what you've learnt so far regarding impulsivity and the brain, here's a quick quiz to test your knowledge:

Consequences of Impulsivity

Risk Factors Involved

People with drug abuse are prone to impulsivity as drugs and substances alter their cognitive and physiological systems. Individuals addicted to drugs will do anything to get the drugs because the urge for the drug is so high and their self-control is less. Drug dependency makes the users unable to function well in the absence of drugs (Bandy & Moore, 2010). Another impulsive risk factor is age. Young children are prone to impulsive behaviours because their thinking capacity has not adequately developed. Moreover, the executive functioning of a child is underdeveloped hence, they are not capable of thinking and reasoning about long-term consequences (Scope, Empson & McHale, 2010). Other risk factors of impulsivity include;

*Incarceration

- Violence

- Gambling Disorder

- Substance Abuse and brain injury

Exposure to violence makes victims susceptible to impulsivity. The brain becomes accustomed to fear such that what they think of is getting away from fights. Therefore, victims of violence are more likely to act on a whim compared to people raised in a calm environment (Ronel, 2011). Families with a history of mood disorders are also a risk factor, which might increase the probability of a person in that family to portray an impulsive behaviour.

The risk factors of impulsive behaviour mostly consist of chronic problems that impair one's ability to control their emotions and actions. Even if a person strives hard to control the impulsive behaviour, there are underlying factors which make them susceptible to it such as kleptomania, pyromania, compulsive sexual behaviour and more (Ronel, 2011). Kleptomania is an obsessive urge to steal, thus kleptomaniacs are well aware of their actions but the impulse to steal is irresistible, and impossible to do away with it.

Behaviour Modification

Behaviour modification is related to methodological behaviorism which deals with the limitation of behaviour-change procedures to observable behaviours. Behaviour modification takes place by use of anticipated consequences such as negative and positive reinforcement (Baumeister, Galliot, DeWall & Oaten, 2006). Human behaviour modification happens through the administration of punishment which will act as a deterrence of repetition of that behaviour. Impulsive behaviour modification is mainly done to increase the level of self-control of a person. The environment plays a significant role in influencing the behavioural change of an impulsive person because impulsivity can be discouraged. One way to treat impulsivity is through Cognitive Behavioural Modification (CBM), and it has been successful in doing so. CBM has been able to assist children in developing self-control despite the treatment taking a while to show significant results (Baer & Nietzel, 1991). Impulsive behaviour may be modified through offering children a reward, not a consequence.

Research shows that impulsive children are more likely to be motivated through rewards as opposed to being punished. However, to make it possible for the change, the reward should be given immediately after achieving the set goal, and the child should choose the reward. Social rewards are better than material rewards which might cause more temptations to the child. Another strategy is teaching an impulsive child how to "self-talk" (Baumeister, Galliot, DeWall & Oaten, 2006). Impulsive individuals lack inner conversation with self which enables one to weigh options, project what might happen if a particular path is taken and much more. They should be taught about cognitively discussing issues with the inner voice to get a better understanding of the best way to respond.

Impulsive individuals should also be taught about stopping before acting on a whim, thinking about the consequences of what they are about to do, speaking out loud what they are thinking about and do what they feel will be good enough for the situation at hand. These steps place action as the last thing unlike for impulsive persons who act without the other steps (Baer & Nietzel, 1991).

Conclusion

Research has demonstrated that the Prefrontal area of the brain has been determined as the source of motivation of impulsive behaviours amongst individuals. The Orbitofrontal cortex is the specific region that is responsible for self-control and if damaged leads to uncontrollable anger outbursts and higher impulsivity levels in individuals. The dual-process is involved between subcortical motivational forces and the development of cortical cognition inside the OBF. The OBF results to impulsivity at an early age of a child before the executive functioning becomes fully developed. If a Behavioural Activation System is dominant in a person, it leads to the inability of self-regulation because the sensitivity to rewards increases and the perception of the need for long-term goals diminishes.

Although these neurobiological factors are the significant causes of impulsivity, the environment is also a considerable influencer of impulsive behaviours. Parents, teachers and the society, in general, can influence the impulsive act positively or negatively. The path that the society and especially parents take when raising a child determine the level of impulsivity a child will have. Different parental approaches explain different levels of impulsivity amongst mature individuals. Children forced to obey social, or school norms may experience ego-depletion due to their brains struggling hard to avoid punishable behaviours. Behavioural modification strategies have proven to be effective treatment methods of impulsivity. However, due to the complexity of compulsive behaviours, treatments should adopt different strategies. Cognitive and behavioural modification improve the levels of self-control and self-regulation amongst individuals hence reduce impulsivity. Although these practices need time to achieve the required goals, they have proven to be a solution to the problem of impulsivity, which is a threat to people who suffer from it.

References

Balleine BW, O'Doherty JP (2010). "Human and Rodent Homologies in Action Control: Corticostriatal Determinants of Goal-Directed and Habitual Action". Neuropsychopharmacology Reviews. 35: 48–69. doi:10.1038/npp.2009.131.

Bandy, T. & Moore, K. (2010). Assessing self-regulation: A guide for out-of-school time program practitioners. Results-to-Research Brief #2010-23. Child Trends. http://www.childtrends.org/Files/Child_Trends 2010_10_05_RB_AssesSelfReg.pdf.

Bari, A. & Robbins, T. W. (2013). Inhibition and Impulsivity: Behavioral and neural basis for response control. Progress in Neurobiology, 108, 44- 79.

Baumeister, R. F., Galliot, M. T., DeWall, C. N., & Oaten, M. (2006). Self-regulation and personality: How interventions increase regulatory success, and how depletion moderates the effects of traits on behavior. Journal of Personality, 74, 1773-1801.

Baumeister, R. F., Sparks, E. A., Stillman, T. F., & Vohs, K. D. (2008). Free will in consumer behavior: Self-control, ego depletion, and choice. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 18(1), 4-13.

Elisabeth Murray, Steven Wise, Kim Graham (2016). "Chapter 1: The History of Memory Systems". The Evolution of Memory Systems: Ancestors, Anatomy, and Adaptations (1st ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 22–24. ISBN 9780191509957. Retrieved 12 March 2017.

Hagger, M. S., & Chatzisarantis, N. L. D. (2016). A multiple preregistered replication of the ego-depletion effect. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 11, 546-573.

Hagger, M. S., Wood, C., Stiff, C., & Chatzisarantis, N. L. D. (2010). Ego depletion and the strength model of self-control: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 136, 495-525.

Hollander, E. & Berlin, H. A. (2008). Neuropsychiatric aspects of aggression and impulse-control disorders. In American Psychiatric Publishing Textbook of Neuropsychiatry and Behavioural Neurosciences. 5th Ed. S.C Yudofsky, & R.E Hales (Eds). American Psychiatric Publishing Inc: Arlington VA.

Kambouropoulos N, Staiger P. K. (2004b). Reactivity to alcohol-related cues: Relationship among cue type, motivational processes, and personality. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors; 18:275–283.

Kambouropoulos N, Staiger P.K. (2004a). Personality and responses to appetitive and aversive stimuli: The joint influence of behavioural approach and behavioural inhibition systems. Personality and Individual Differences; 37:1153–1165.

Lopez-Vergara, H. I., Colder, C. R., Hawk, L. W., Wieczorek, W. F., Eiden, R. D., Lengua, L. J., & Read, J. P. (2012). Reinforcement sensitivity theory and alcohol outcome expectancies in early adolescence. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 38, 130-134.

Muraven, Mark; Greg Pogarsky; Dikla Shmueli (June 2006). "Self-control Depletion and the General Theory of Crime". J Quant Criminol. 22 (3): 263–277. doi:10.1007/s10940-006-9011-1.

Reeve, J. (2015). Understanding Motivation and Emotion. (6th Ed.). Wiley: Hoboken NJ.

Ronel, N. (2011). "Criminal behavior, criminal mind: Being caught in a criminal spin". International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 55(8), 1208 - 1233.

Schultz W, Tremblay L (2006). Involvement of primate orbitofrontal neurons in rewards, uncertainty, and learning. In Zald DH and Rauch SL (Eds.) The Orbitofrontal Cortex. Oxford: University Press.

Scope, A., Empson, J., & McHale, S. (2010). Executive function in children with high and low attentional skills: Correspondences between behavioural and cognitive profiles. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 28, 293-305.

Smillie, L. D., Dalgleish, L. I., & Jackson, C. J. (2007). Distinguishing between learning and motivation in behavioural tests of the Reinforcement Sensitivity Theory of personality. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 33, 476-489.

Walton M. E.; Behrens T. E.; Buckley M. J.; Rudebeck P. H.; Rushworth M. F. (2010). "Separable learning systems in the macaque brain and the role of orbitofrontal cortex in contingent learning". Neuron. 65 (6): 927–939.

Yuan, Peng; Raz, Naftali (2014-05-01). "Prefrontal cortex and executive functions in healthy adults: a meta-analysis of structural neuroimaging studies". Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 42: 180–192.