What is homesicknesses and what are the associated risk and protective factors?

Overview

It has been long recognised by scholars that home, consisting of familiar environments along with relationships, routines and feelings allow individuals to develop and maintain their personal and social identities and establish a sense of continuity within their lives (Scharp, Paxman, Thomas 2015). So what are the proceeding repercussions when one departs from home? The purpose of this book chapter is to explore the phenomena of homesickness and develop a greater psychological understanding. Through this process, exploration of emotional, grief and attachment theories will allow for the individuals to develop coping processes and theoretical-based prevention and applied clinical intervention that is desperately needed.

| Learning Outcomes

Upon completion of this chapter, the following criteria should be satisfied:

|

Defining homesickness

There are many definitions surrounding homesickness and although there is no un-ambiguous definitions, the conceptualisation remains the same. Homesickness is a cognitive-emotional state of distress caused by actual or anticipated separation from home. The phenomenology of homesickness is distinguished by intense longing for and preoccupying thoughts of home. This cognitive hallmark ensures homesickness is unique to other forms of anxiety or mood disorders although sharing similarities (this will be explored further). In this context home is not used in the literal sense, it can refer to family, close friends, familiar surroundings, daily routines and conveniences and even foods one has become accustomed to. (Thurber 1999).

It is important to note that HS is often confused with culture shock, however homesickness is considered a by-product of culture shock in the sense that culture shock refers to confusion surrounding the norms of recent exposure to a new culture. Sojourns away will face the prospect of returning home while HS can include permanent relocation (Stroebe, Schut, Nauta 2016)

Prevalence of homesickness

The prevalence of homesickness is particularly difficult to assess given that it is not a continuos phenomenon and the onset of homesickness can occur suddenly and unexpectedly in a periodical manner (excluding severe cases). It is reported the complex cognitive-emotional phenomena is experienced by between 83 - 95% of people within their lifetime, regardless of age groups, culture or gender (Bardelle, Lashley 2015).

It is difficult to assess how long HS may last, assumptions would suggest the symptoms decline the longer one is exposed to the new environment however results of studies have not supported this. For example 39% of first year students in a study who experienced HS, claimed it quickly declined while students in another study experiencing severe homesickness 51% of the population still reported experiencing HS 3 years later.

Homesickness is a universally experienced phenomenon and can manifest itself in a plethora of circumstances. Here are some of the common populations in which homesickness is experienced.

- Children visiting school camps

- Children, adolescents and young adults attending university (both domestic and international)

- Extended stays in hospital

- Occupations that include extended periods away from 'home' (e.g. army recruits)

- Elderly relocating from home into care services

| History of Homesickness

TEDx TALK - Susan Matt, an American historian who researches the effect of emotions goes into great depths exploring the history of homesickness. From English Puritans, rugged pioneers, war heroes and goldminers shedding tears and experiencing grave sadness over their previous home. Watch the video here! https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6WjzhuFpNDc |

Symptomatology of homesickness

Separating symptoms of homesickness and the correlates and consequences associated has proven difficult, HS shares commonalities with depression and anxiety for example, however could be considered as consequences of HS. (Bardelle, Lashley 2015) stress the importance to accept homesickness as an illness. In severe cases homesickness can lead to social phobias, premature return home and avoiding sojourns or separation from loved ones in the future (Stroebe, Schut, Nauta 2016).

The psychological disorders and symptoms caused by HS can have significant effect on an individuals health and welfare. Four key characteristics have been identified.

Somatic

Somatic symptoms are frequently experienced in homesickness, these include include sleep disturbances, loss of appetite and weight, gastric and intestinal pain, headaches and chronic fatigue. Self reports regarding a decline in physical health after arriving in new environment are also associated with the emotion of HS.

Cognitive

Cognitive symptoms are the key indicator in identifying homesickness with obsessional thoughts of home and the attachment objects associated as the defining symptom. Other frequent cognitive symptoms include projecting negative thoughts and views onto the new environment and absentmindedness. Homesickness amongst students attending private/boarding school and university have reported greater cognitive failures including poor concentration, handing in assignments late, decreased quality of work and higher test score anxiety. These findings illustrate the potential impact on academic performance (Stroebe, Van Vliet, Hewstone, Willis 2002).

Behavioural

At a behavioural level individuals display a lack of interest or initiative in their new environment, this is evident through social withdrawal and isolation. Homesickness has been found to express itself via internalising its problems, with one exception. Children suffering from moderate to severe homesickness will present atypical, external behaviour often violent and delinquent in nature; fighting, swearing, vandalising new environment and acting out of character. It is suggested that these children (predominately boys) show externalised behaviours in order to attract attention from camp leaders or temporary carers. Failed attempts at seeking social support lead to feeling further isolated.

Emotional

Reduced emotional satisfaction (e.g. the feelings of disappointment) regarding the new environment often occurs with those experiencing adverse reactions face unpleasant realities. This is said to be due to initial unrealistic expectancies carried by the individual. Emotional characteristics of HS can include feelings of loneliness, low self-esteem and worthlessness, if one suffers further can lead to apathy and listlessness. HS is often felt in conjunction with depressive and anxiety related symptoms. These distressing and debilitating symptoms warrant the further exploration of its study

Protective and risk factors

Risk factors

Risk factors are contributing agents that make more prone to experiencing homesickness and its consequences.

Some factors that have been suggested yet require further research include; geographical location (distance) and psychological state upon and prior to departure .

The identified risk factors appear in the table below.

| Risk Factor | |

|---|---|

| Experience | Experience refers to the exposure one has previously had away from 'home'. It is a strong predictor of homesickness, with age a strong correlate of experience.

For example; an 11 year old boy that attends weekend camps with his local scouts group will cope better than an 8 year old girl having to spend a weekend with relatives for the first time. Experience away from home allows an individual to develop coping strategies. |

| Parenting Styles. |

|

| Attachment Styles | Those possessing an anxious ambivalent attachment style are most likely to experience homesickness when separation from home occurs. Separation in children from their caretaker results in anxious, seeking, violent and distressed behaviour, if ones needs are not satisfied in severe cases this can lead to apathy and helplessness.

While it is argued that adults can posess similar attachment styles manifesting itself in intimate relationships or marriages and relationships between friends, the lost of immediate interaction with this significant person |

| Personality Factors | There are two key personality factors identified that contribute to ones vulnerability in experiencing homesickness. Higher scores of neuroticism and lower scores of extraversion are associated with the development of HS and debilitating the recovery process.

Other factors for adults include; high harm avoidance and rigidity, low perceived control, low levels of self directness and assertiveness, whether an individual demonstrates optimistic or pessimistic tendencies |

Protective factors

Protective factors are constructs that reduce the likelihood one experiencing homesickness or the intensity of the related symptoms. The identified protective factors appear in the table below.

| Protective Factor | |

|---|---|

| Age | Age is regarded as a substitute for experience and is considered the most common protective factor in ones susceptibility in experiencing homesickness. It is assumed that throughout childhood into adult one will develop coping strategies and be able to spend time away from their primary caregivers, loved ones and home. |

| Attachment Styles | Secure attachment style is associated with indepednce, a strong desire to explore, high social skills which allow individuals to transition fluidly into a new environment. |

| Parenting Styles | Authoritative - Children and those heading to college show high self reliance and higher self-esteem. Thus allowing them to be better equipped independently. Two contributing factors of the parenting style limit the susceptibility to HS.

|

Diagnosis and aetiology

separation anxiety disorder (SAD) and homesickness share similarities in their manifestations; intense anxiety concerning the separation from home. However there are key differences that separate them from one another. A child can still suffer from separation anxiety disorder in their own home environment when their primary caregiver (the attachment figure) leaves the immediate vicinity.

According to adjustment disorder the DSM-IV criteria states that it is a maladaptive response to identifiable psychosocial stressors. Reaction must be in excess of a normal and expected reaction to the identified stressor. Other symptoms can include impaired academic or occupational performance and hinder interpersonal relationships. Severe homesickness is related to two of the six subtypes of symptoms. These are depressed mood with physical complaints and depressed mood while being away from home and reoccurring thoughts about home (refer cognitive and somatic symptoms). If these symptoms do not hinder daily functioning then according to DSM-IV criteria this must be assessed as a regular reaction to be away from home (Van Tilburg, Vingerhoets & Van Heck 1999).

Models of emotion and homesickness

Dual Process Model

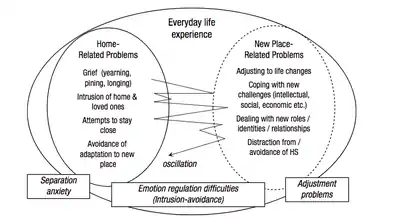

homesickness has been proposed as a "mini" grief like phenomenon, with similarities in the underlying structure, manifestation and consequences to those who have experienced the death of a loved one. Homesickness occurs in the separation of a loved one, with the reoccurring feelings of longing for aspects of a person, a feature paramount in bereavement. Within the domain of homesickness these aspects can also include the home environment and aspects of their previous life such as daily routines (Stroebe, Schut & Nauta 2016). This model poses that dual, regulatory processes; the separation phenomena of HS and the relocation difficulties may occur collaboratively to exacerbate ones physiological and psychological health (as seen in Figure 3). If coping does not take place, this then leads to the ruminative thoughts of home and maladaptive cognitive behaviours.

The dual process approach allows for the understanding of negative spiralling emotions and symptoms one can experience. Dual process model (DPM) treatment comprises of regulation of loss and restoration focused training this could prove widely effective in addressing someone's ruminative thoughts and feelings of HS. Further research and application is required in order to assure

Cognitive appraisal theory

In both an adult or child's daily life they can face a variety of stressful events. Exposure to these events can lead to significant strain one one's psychological and physical health and well-being. Some of these stressors can include significant life changes (e.g. residential relocation), relationship breakdown and illness. Cognitive appraisal is thought to be a process, in which ones reaction to when exposed to these situations is not determined by the objective situation yet it is rather determined by ones subjective interpretation of the situation.

Personality studies within adults supports appraisal styles an example of this; an older male who views change as normal welcomes new challenges will experience more control in their own ability to handle an unfamiliar situation or environment, supporting experience (lack of) as a risk factor in ones vulnerability in feeling homesick (hood, power, hill 2009).

The transactional model of stress can be applied when addressing homesickness, the model is based around primary and secondary appraisals. Primary appraisals refers to the personal relevance the situation holds and the value it is perceived to carry. While secondary apprasial focuses on the evaluations of options to cope with the situation, whether that he/she holds the abilities necessary in order to cope with the situation. Both primary and secondary appraisals compliment each other, determinig the extent of stress and negative affect one experiences. In short, stress occcurs when a sistuation is deemed dangerous to ones well being (primary appraisal) and that he/she has insufficient resources in order to cope with the environmental demand. Evidence has found that personality variables; neuroticism, extraversion and openness also contribute to experience of stress lack of self confidence within coping processes (secondary appraisal) (Zureck, Alstotter-Gleich, Gerstenberg, Schmitt 2015).

To put this into practical context; Susan begins her semester overseas an incredible opportunity she has always dreamt of. However upon arrival, she is overcome the size of the new campus, the fact she does not know anyone at her new university induces an overwhelming anxiety, she now fears she will fail the semester and cannot stop thinking about home. Cognitive appraisal would suggest that the demands of her external environment create negative onset of homesickness and anxiety as she has insufficient resources to cope with the environment.

Coping with homesickness

Brief cognitive behavioural therapy used in conjunction with anti depressants has been found significant in reducing the feelings of homesickness and depression amongst international students Through enhancing knowledge and awareness of the experienced negative emotions as well as providing self management techniques. Re-framing the pre-occupying thoughts of former environment and re-focusing thoughts on the current environment is desirable. It was found amongst 520 international students that depressive and homesickness symptoms peaked at the 6 week period (Saravanan, Mohamad 2017).

For children (Thurber, Walton 2006)

- Building experience through practicing time away from home with other family members (one-two nights preferred). Parents are to avoid making contact with child during stay.

- Educate the child that missing home is normal and that everyone does so at some stage. It is good that he/she misses home, it means they care about home.

- Openly discuss coping strategies with the child (e.g. thinking about good things to come promotes optimism).

- Incorporate the child in learning about their future environment (e.g. school camp, relocating to new city, new school) allowing the child to increase their familiarity prior to is known to decrease anxiety.

For university students

- Do not carry pre conceived ideas on what to expect, embrace the experience of personal growth, be open-minded and curious to learn about your new environment.

- Understand that times of feeling low are normal throughout this transition period and better times are to come.

- Seek to join extra curricular activities or groups of personal interest outside of studies, keep in touch with family and friends back home - remember socialising is an important aspect.

- Establish a level of routine to keep busy and your mind occupied. Staying on top of studies is important. Break the academic workload into small goals.

- Keeping physically active and maintaining a nutritionally balanced diet. Be cautious regarding the consumption of alcohol and other depressants.

- Importantly if you feel the need, seek the institutions counselling services, they can offer a judgement free, safe space to talk through your emotions.

Conclusion

Questions remain over how effectively HS can be measured as there are a number of issues effecting the validity and consistency of a universal measure. First the number of definitions surrounding the phenomena discarding any application of a universally-operational definition. Individuals may differ in their focus of HS for example; one missing their family home while another longing for their best friend. How much weight can be assigned to either position? As well as the intensity in which two individuals will experience homesickness over the same context (e.g. missing family pet).

experienced in its mild state allows both children and adults personal growth, gain a wealth of new life experiences and the ability to adapt to novel situations. However experienced homesickness in intense severity can be detrimental in ones physiological and psychological well being. HS is experienced by almost everyone at some stage in their life, it is important to understand that the feelings and symptoms associated are common and that there are a number coping strategies applicable in reducing the severity of HS.

Food for thought.

Very minimal research has been conducted regarding the advancements in technology and social media and wether this can help ease the suffering of homesickness and foster positive well-being, growth and coping strategies or whether constant exposure to ones previous home and everything associated with it (e.g. friends and families social events) can be detrimental into priming the obsessional thoughts of home. An important question to consider as possible area for future research.

While the advancements in international tourism, migration, occupational and educational opportunities warrant further research and treatment methods.

See also

References

Bardelle, C., & Lashley, C. (2015). Pining for home: Studying crew homesickness aboard a cruise liner. Research In Hospitality Management, 5(2), 207-214.

Hood, B., Power, T., & Hill, L. (2009). Children's appraisal of moderately stressful situations. International Journal Of Behavioral Development, 33(2), 167-177. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0165025408098011

Homesickness while travelling. (2017). ANU. Retrieved 15 October 2017, from http://www.anu.edu.au/students/health-wellbeing/mental-health/homesickness-while-travelling

Nijhof, K., & Engels, R. (2007). Parenting styles, coping strategies, and the expression of homesickness. Journal Of Adolescence, 30(5), 709-720. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2006.11.009

Saravanan, C., Alias, A., & Mohamad, M. (2017). The effects of brief individual cognitive behavioural therapy for depression and homesickness among international students in Malaysia. Journal Of Affective Disorders, 220, 108-116. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2017.05.037

Scharp, K., Paxman, C., & Thomas, L. (2016). “I Want to Go Home”. Environment And Behavior, 48(9), 1175-1197. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0013916515590475

Stroebe, M., Schut, H., & Nauta, M. (2015). Homesickness: A systematic review of the scientific literature. Review Of General Psychology, 19(2), 157-171. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/gpr0000037

Stroebe, M., Schut, H., & Nauta, M. (2015). Is Homesickness a Mini-Grief? Development of a Dual Process Model. Clinical Psychological Science, 4(2), 344-358. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/2167702615585302

Stroebe, M., Vliet, T., Hewstone, M., & Willis, H. (2002). Homesickness among students in two cultures: Antecedents and consequences. British Journal Of Psychology, 93(2), 147-168. http://dx.doi.org/10.1348/000712602162508

Thurber, C., & Walton, E. (2007). Preventing and Treating Homesickness. American Academy Of Pediatrics, 119(1), 192-201. http://dx.doi.org/10.1542/peds.2006-2781

Tilburg, M., Vingerhoets, A., & Heck, G. (1999). Determinants of homesickness chronicity: coping and personality. Personality And Individual Differences, 27(3), 531-539. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/s0191-8869(98)00262-1

Zureck, E., Altstötter-Gleich, C., Gerstenberg, F., & Schmitt, M. (2015). Perfectionism in the Transactional Stress Model. Personality And Individual Differences, 83, 18-23. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2015.03.029