Why are people disappointed with personal past acts, inaction and behaviours?

Overview

The purpose of this chapter is to develop a psychological understanding of the emotion, regret. There are multiple processes involved with not only the experience of regret, but also the anticipation of regret. Regret can impact on all aspects of human existence and as Coricelli and colleagues (2005) noted, it may be impossible not to experience regret in an individual's lifetime. This chapter explores regret, why we experience regret and how we can regulate it. The parts of the brain which are active when experiencing regret are examined and new environments where people can experience regret, such as online, are noted. The different ways people experience regret are also briefly explored.

Question mark2 Learning outcomes

|

Definition

Landman (1993) defined regret as the persistence of the possible, the thought(s) of what could have been. Regret is a painful cognitive/emotional state of feeling sorry for misfortunes, limitations, losses or mistakes (Landman, 1993). Regret is not commonly considered to be one of the basic emotions but rather a complex anticipatory and procedural experience (Zeelenberg & Pieters, 2007). Characteristics of disappointment, sadness, remorse, and guilt are usually felt when one is dealing with regrets.

Regrets can be distinguished by being future- or past-related. For example, one individual may regret making the wrong career choice (past-related) while another may regret not being able to see their grandson (future-related) (Tomer & Eliason, 2008). Past-related regrets can be further separated by actions/commission or inaction/omission (Tomer & Eliason, 2008). An example of a commission regret could be a husband regretting treating his spouse badly, while an example of an omission could be not taking the time to travel around the world before passing away. People are motivated to regulate their regrets even in a normal state, because regrets are perceived as aversive to the self (Zeelenberg & Pieters, 2007).

Regrets have cognitive and emotional reactions when people consider their past wrongdoing in omission or commission, or when they consider their future and the probability of not achieving important personal goals before they die (Neimeyer et al., 2011). The concept of self-blame is related to regret because most regretful situations indicate that things could have been different if the right choices were made (Connolly & Zeelenberg, 2002). Such situations do not always need to be bad to experience regret. For example, an individual decides to drive home after a party where they had more than the legal limit of alcohol and made it home safely. Driving above a the alcohol limit is illegal and can impair driving skill. Because the individual made it home safely the outcome of the situation is good, but the person might still blame themselves for taking such a dangerous decision (Connolly & Zeelenberg, 2002).

Regret theories

The first regret theories originated in economics research as a way to understand what role the emotion played in spending, investing, and losing money and how this shapes our behavioural responses (Gilovich & Medvec, 1995). The difference in assets and other alternatives played a large part in these early economic theories (Gilovich & Medvec, 1995). However, because of the very narrow scope or definition that economic theorists decided to focus their attention, it was difficult to apply this theory in a broader psychological sense. A psychological theory of regret would seek to understand feeling and emotion rather than just behavioural responses.

Counterfactual thinking

When researching regret it is difficult not to see some similarity to counterfactual thinking or the thoughts of what might have been in regards to negative emotional consequences. Counterfactual thinking theory addressed the weaknesses of the early regret economic theories (Gilovich & Medvec, 1995) by addressing the unpleasant emotional experiences that trigger regret (Roese, 1997). According to counterfactual thinking theory developed by Roese (1997), events are compared to alternative events that had the possiblity of coming to fruition. These thoughts are almost automatic and arise from the demand to respond to specific queries, goals, or intentions. There are two mechanisms that cause counterfactual consequences: contrast effects and causal inferences. Contrast effects occur when there is a notable difference between what there was before and what there is now. For example, a lukewarm bath feels colder, by contrast, if one has just spent half an hour in a heated spa. Causal-inference effects, however is drawing a conclusion about a casual connection based on the conditions of the occurrence of an effect. Contrast and causal-inference effects have been linked to a number of counterfactual consequences which allow counterfactual thinking to activate (Roese, 1997).

Counterfactual thinking can be further separated into upward and downward counterfactual thinking. Upward counterfactual thinking focuses on how the situation could have been better if things were done differently (Roese, 1997). Downward counterfactual thinking focuses on how the situation could have been worse (Roese, 1997). A very good example of upward and downward counterfactual thinking can be seen with Olympic medal winners. Silver medalists commonly experiences upward counterfactual thinking as they realise how close they were to winning a gold medal, while a bronze medalist commonly experiences downward counterfactual thinking when they focus on how they could have not even won a medal if their performance was just slightly poorer than 4th place (Markman & Tetlock, 2000). Emotional Amplification is a concept derived from counterfactual thinking which states that people react more strongly to events where it is easy to imagine a different outcome (Gilovich & Medvec, 1995). A finding which has amassed a large amount of empirical support around counterfactual thinking is that people experience more regret over negative outcomes from recent actions rather than from equally negative outcomes that result from actions in the past (Gilovich & Medvec, 1995). Counterfactual thinking can be seen as the mechanism which breeds regret, as it explains the ways individuals may perceive alternative outcomes.

A possible criticism of the counterfactual thinking theory proposed by Girotto, Legrenzi, and Rizzo (1991) is that sometimes there is no counterfactual thinking consequence from an outcome. A recoverable error could be judged irrecoverable as a consequence of the incapacity to imagine the right alternative to the action that caused the error. This is a idea which was not stated in the original counterfactual thinking theory.

Regret regulation theory

Regret research from psychology, economics, marketing, and related disciplines has been reviewed and developed into regret regulation theory (Zeelenbeg & Pieters, 2007). Currently, the theory is still in its conception and authors Zeelenbeg & Pieters (2007) are willing to revise the theory to encompass all aspects of regret so they can create a highly adaptable and robust theory for other researchers to utilise.

Regret regulation theory puts forth a series of propositions which seek to identify regret:

- Regret is an aversive, cognitive emotion that people are motivated to regulate in order to maximise outcomes in the short and long run.

- Regret is a comparison-based emotion of self-blame, experienced when people realise or imagine that their present situation would have been better had they decided differently in the past.

- Regret is distinct from related other specific emotions such as anger, disappointment, envy, guilt, sadness, and shame and from general negative affect on the basis of its appraisals, experiential content, and behavioural consequences.

- Individual differences in the tendency to experience regret are reliably related to the tendency to maximise and compare one’s outcomes.

- Regret can be experienced about past (“retrospective regret”) and future (“anticipated or prospective regret”) decisions.

- Anticipated regret is experienced when decisions are difficult and important and when the decision maker expects to learn the outcomes of both the chosen and rejected options quickly.

- Regret can stem from decisions to act and from decisions not to act: The more justifiable the decision, the less regret.

- Regret can be experienced about decision processes (“process regret") and decision outcomes (“outcome regret”).

- The intensity of regret is contingent on the ease of comparing actual with counterfactual decision processes and outcomes, and the importance, salience and reversibility of the discrepancy.

- Regret aversion is distinct from risk aversion, and they jointly and independently influence behavioural decisions.

- Regret regulation strategies are goal-, decision-, alternative-, or feeling-focused and implemented based on their accessibility and their instrumentality to the current overarching goal.

Roese, Summerville, & Fessel (2007) have made many justified criticisms of regret regulation theory. Firstly the focus on regret regulation may be too narrow, while the broader theoretical picture becoming lost. Regret regulation is secondary to behaviour regulation, which is the management of effective daily behaviour. Roese, Summerville, and Fessel (2007) argue that emotion is only one part of the regulatory loop mechanism, which governs single and sequential actions that together ensure survival and success. This is to say that people do not seek to regulate their inner regret for the sake of it, but to attain better outcomes which in turn regulates behaviour.

Consistent themes in regret research

A meta-analysis of 11 regret ranking studies conducted by Roese and Summerville (2005) in North America found an order of topics which are most regretted by individuals:

- education

- career

- romance

- parenting

- the self

- leisure

There has been much thought into why this order is consistent among studies and what makes these topics special in terms of regret (Roese & Summerville, 2005). The opportunity principle seeks to explain this finding, as lost opportunity often creates regret (Roese & Summerville, 2005). According to this principle, regret persists in situations where opportunity for positive action remains high. Applied to education, if an individual did not apply themselves in school before graduating they always have the opportunity to come to university. Nowadays community colleges and student aid programs make it easier to pursue higher education, but this potential for positive action may lead individuals to become doubtful, fearful or worried. This explanation is interesting when considered cross-culturally. Perhaps in other countries where education is not as accessible there may be a shift in the regrets people feel are most regretful. Currently research has not been conducted to answer this question. Subsequent studies have discovered that high opportunity directs attention to more intense regrets than low opportunity and life domains that participants see as being high opportunity were identified as vividly regretful (Roese & Summerville, 2005).

Physiology of regret

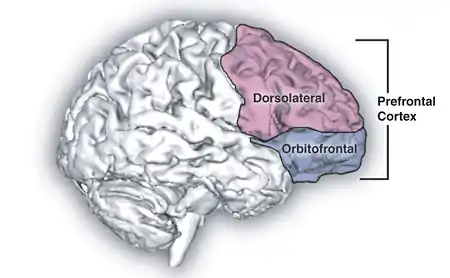

By conducting experiments with simple gambling tasks, neuroscience research has the ability to identify specific brain areas which are important in experiencing regret (Camile et al., 2004; Coricelli et al., 2005; Nicole et al., 2011; McCormack et al., 2016). Camille and colleagues (2004) conducted an experiment with participants who had orbitofrontal cortex damage in a gambling scenario. Participants without such damage to this particular brain area behaved as anticipated to an adversive gambling outcome; feeling disappointment, sadness, and remorse. However, participants with orbitofrontal cortex damage did not experience any regret over decisions that did not go according to plan. Follow-up studies with fMRI-techniques confirmed that the orbitofrontal cortex has a mediating role in the experience of regret.

Interestingly, in the case of anticipating regret the amygdala may also be involved (Coricelli et al., 2005). In an experiment conducted by Coricelli and colleagues (2005), participants became increasingly regret-aversive in a gambling task. This cumulative process was reflected by changes in responses in the amygdala as well as the orbitofrontal cortex from an fMRI analysis. This suggest that the same neural circuitry mediates direct experience of regret and its anticipation. Further studies indicated that there is an enhanced amygdala response to regret-related outcomes when they are associated with high, as compared to low, responsibility decisions (Nicolle et al., 2011). The possible reason for this amygdala activity in high responsibility decisions is that the amygdala communicates information necessary for acquiring stimulus–reward associations to the orbitofrontal cortex (Nicolle et al., 2011). The orbitofrontal cortex uses this information to guide behaviour in a given decision, which allows behaviour to be formative with strategic goals (Nicolle et al., 2011).

But when does this experience of regret begin to develop? From what is known about the development of the brain, it can be assumed that this brain area may develop at a certain time of life. A recent study conducted by McCormack and collegues (2016) aimed to answer this developmental question of regret acquisition. Using a simplified version of a gambling task with children aged 6 or 7 years and an older group of 8- and 9-year-olds, children’s feelings were measured about their choices during a game. The findings suggest that children as young as 6 or 7 years experience regret similar to that experienced by older adults. Futhermore, a study by Guttentag and Ferrell (2004) supports this developmental claim as it was found that the emotional responses of 7-year-olds took into consideration their action and what might have been if they had acted differently, which is an example of an omission. 5- year-olds in their study did not experience such regret, as it can be argued that the orbitofrontal cortex has not yet developed to mediate regret. Although the topics in which young children regret would be very different from those experienced in later life, this research highlights the developmental stage in which regret can be perceived.

Regrets online

Social media makes it easier for people to stay in touch and communicate, but the content they post can easily lead to a regrettable decision. It is common for individuals to post or publish information that should be left private. Some may not understand the scope of the internet or the fact that when something is posted online it is there forever; even if deleted the content can live on through a screenshot of the webpage. It seems that everyone knows of a story where someone has ended their relationship, been fired or suspended for their conduct online (Wang et al., 2011). But why do people act in such ways beforehand? Wang and colleagues (2011) found the most common reasons why people post items on social media that they later regret are:

- they want to be perceived in favourable ways.

- they do not think about their reason for posting or the consequences of their posts.

- they misjudge the culture and norms within their social circles.

- they are in a “hot” state of high emotion when posting, or under the influence of drugs or alcohol.

- their postings are seen by an unintended audience.

- they do not foresee how their posts could be perceived by people within their intended audience.

- they misunderstand or misuse the hosting platform.

Furthermore, online it can be difficult to identify the audience of a post, control the scope of one’s actions, and the reactions to something published. The repercussions that follow from online regret can be serious, with stories being told daily of people being fired from their employment, suspended from schooling, bullied or blackmailed for their actions online. Users have found ways that they can avoid making a mistake online or handle the regret of their actions. Many decide to keep their public and private lives separated online. This can be done by not displaying anything that others wouldn't like to see. This rule may apply for family members, co-workers, bosses, school staff, etc. Otherwise, if a post has already been created that is detrimental to someone's image, the post can usually be deleted and an apology can be made to reduce regret. Users can also opt to change their privacy settings on their profiles to "friends only" to avoid others outside of the users "friends list" seeing their activity or pictures. The wisest choice is to self-censor content and to be careful about what could be interpreted by a post.

Regrets in old age

An Australian caregiver's experiences in palliative care helped to compile a list of the top five regrets of the dying (Warren, 2012):

- “I wish I'd had the courage to live a life true to myself, not the life others expected of me.”

- “I wish I hadn't worked so hard.”

- “I wish I'd had the courage to express my feelings.”

- “I wish I had stayed in touch with my friends.”

- “I wish I had let myself be happier."

This list is an example of the type of regrets which persist and are not discarded when someone is reaching the end of their life. Death and emotion has a link to the end of life regrets that the elderly experience.

Some older age adults forget to, or have trouble with expressing their regrets to their family and loved ones. Since regret feels bad because it implies a fault in personal action (Roese & Summerville, 2005) confessing a regret can often be avoided by an individual. You yourself might have an experience where you spent a large amount of time not expressing a regret. The Standford Letter Project is an initiative in the United States which gives the elderly a chance to express their regrets through a simple and free letter template (Periyakoil, 2016). The letter can either be shared straight away, or stored to be given to a loved one after passing. Why do regrets seem to diminish slightly when individuals enter old age? A study by Wrosch and Heckhausen (2002) investigated this question by examining the experience of omission regrets in a sample of young, middle-aged, and older adults. They found that the older age group rarely have commission related regrets. This seems to imply that when opportunity becomes limited in older age, regrets start to decrease.

Cultural differences

A person's culture can influence how they behave, think and experience the world. For example, life in collectivist cultures that admire duty and social harmony might have more regrets of action (Gilovich et al,. 2003). Psychologists have been very interested in discovering any differences between individualist and collectivist cultures for this purpose. When Gilovich (2003) and colleagues researched this question alongside five other studies from varying cultures they found that participants exhibited the same tendency to regret inaction more than action. But what of individualistic or collectivistic regret? Is there really a difference between cultures? One would think that regrets would stay consistent with the culture from which one is from. Surprisingly, Gilovich (2003) and colleagues found that even those of participants from collectivist cultures reflected purely selfish concerns. Both Chinese and Americans were more likely to regret inaction than to regret actions in all of the previous cross-cultural studies (Komiya et al., 2011). However, a study by conducted by Komiya and colleagues (2011) found that Japanese participants experienced more regret than Americans in interpersonal situations. However, Americans felt as much regret as Japanese in self situations. The tendency to regret inaction over action was more pronounced in self situations than in interpersonal situations and was more pronounced among Americans than Japanese. A study on terminally ill elders in North America (Gardner & Kramer, 2010) reported that some patients worried about the medical bills, taxes, or loss of income that would affect the family or loved ones that had been caring for them. Many also commented that they would not be able to help or look after their family after they had passed.

Gender differences

There are very few sex differences in regret or counterfactual thinking that is evident in past research (Roese et al., 2006). Findings from three studies showed that within romantic relationships, men indicate regrets of inaction over action, while women report regrets of inaction and action equally (Roese et al., 2006). For example, males tend to regret not pursuing more relationships with females that they had admired when they were younger. Research suggests that this difference is a product of the evolutionary perspective, as men can invest little into parental investment allowing them to have multiple sexual partners while women will fall pregnant with a child and commit to child rearing (Roese et al., 2006).

Quiz

|

Choose the correct answers and click "Submit":

|

Conclusion

This chapter examines why people are disappointed in their personal past acts, inaction and behaviours. The counterfactual thinking theory and regret regulation theory were presented to provide a framework in which to answer this question. Research on the main themes of regret were highlighted - the top regret being to not get more or better education. The brain areas of the amygdala and orbitofrontal cortex were identified as having a mediating role for the experience of regret. The most common online regrets were discussed along with how individuals can avoid such regrets. The regrets of old age were briefly noted. Culture and gender differences were both found to have little difference in the experience of regret.

See also

References

Coricelli, G., Critchley, H. D., Joffily, M., O'Doherty, J. P., Sirigu, A., & Dolan, R. J. (2005). Regret and its avoidance: a neuroimaging study of choice behavior. Nature neuroscience, 8(9), 1255-1262.

Gardner, D. S., & Kramer, B. J. (2010). End-of-life concerns and care preferences: congruence among terminally ill elders and their family caregivers. OMEGA-Journal of Death and Dying, 60(3), 273-297.

Gilovich, T., Wang, R. F., Regan, D., & Nishina, S. (2003). Regrets of action and inaction across cultures. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 34(1), 61-71.

Gilovich, T., & Medvec, V. H. (1995). The experience of regret: what, when, and why. Psychological review, 102(2), 379.

Gilovich, T., Medvec, V. H., & Chen, S. (1995). Commission, omission, and dissonance reduction: Coping with regret in the" Monty Hall" problem.Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 21(2), 182-190.

Girotto, V., Legrenzi, P., & Rizzo, A. (1991). Event controllability in counterfactual thinking. Acta Psychologica, 78(1-3), 111-133.

Guttentag, R., & Ferrell, J. (2004). Reality compared with its alternatives: Age differences in judgments of regret and relief. Developmental Psychology, 5, 764–775.

Komiya, A., Miyamoto, Y., Watabe, M., & Kusumi, T. (2011). Cultural grounding of regret: Regret in self and interpersonal contexts. Cognition & emotion, 25(6), 1121-1130.

Landman, J. (1993). Regret: The persistence of the possible. Oxford University Press.

Markman, K. D., & Tetlock, P. E. (2000). Accountability and close-call counterfactuals: The loser who nearly won and the winner who nearly lost. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 26(10), 1213-1224.

McCormack, T., O’Connor, E., Beck, S., & Feeney, A. (2016). The development of regret and relief about the outcomes of risky decisions.Journal of experimental child psychology, 148, 1-19.

Nicolle, A., Bach, D. R., Frith, C., & Dolan, R. J. (2011). Amygdala involvement in self-blame regret. Social Neuroscience, 6(2), 178-189.

Neimeyer, R. A., Currier, J. M., Coleman, R., Tomer, A., & Samuel, E. (2011). Confronting suffering and death at the end of life: The impact of religiosity, psychosocial factors, and life regret among hospice patients. Death Studies, 35(9), 777-800.

Periyakoil, V. J. (2016, September, 7). Writing a ‘Last Letter’ When You’re Healthy. New York Times Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com

Pieters, R., & Zeelenberg, M. (2007). A theory of regret regulation 1.1. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 17(1), 29-35.

Roese, N. J., & Summerville, A. (2005). What we regret most. and why. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 31(9), 1273-1285. doi:10.1177/0146167205274693

Roese, N. J., Pennington, G. L., Coleman, J., Janicki, M., Li, N. P., & Kenrick, D. T. (2006). Sex differences in regret: All for love or some for lust?. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 32(6), 770-780.

Roese, N. J., Summerville, A., & Fessel, F. (2007). Regret and behavior: Comment on Zeelenberg and Pieters. Journal of consumer psychology: Society for Consumer Psychology, 17(1), 25.

Roese, N. J. (1997). Counterfactual thinking. Psychological bulletin, 121(1), 133.

Timmer, E., Westerhof, G. J., & Dittmann-Kohli, F. (2005). "when looking back on my past life I regret..": Retrospective regret in the second half of life. Death Studies, 29(7), 625-644.

Tomer, A., & Eliason, G. T. (2008). Regret and death attitudes. In A. Tomer, A. G. T. Eliason, & P. T. P. Wong (Eds.), Existential and spiritual issues in death attitudes (pp. 159–172). New York: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Wang, Y., Norcie, G., Komanduri, S., Acquisti, A., Leon, P. G., & Cranor, L. F. (2011, July). I regretted the minute I pressed share: A qualitative study of regrets on Facebook. In Proceedings of the Seventh Symposium on Usable Privacy and Security (p. 10). ACM.

Warren, B. (2012). The Top Five Regrets of the Dying: A Life Transformed by the Dearly Departing by Bronnie Ware. Proceedings (Baylor University. Medical Center), 25(3), 299.

Wrosch, C., & Heckhausen, J. (2002). Peceived control of life regrets: Good for young and bad for old adults. Psychology and aging, 17(2), 340.

Zeelenberg, M., & Pieters, R. (2007). A theory of regret regulation 1.0. Journal of Consumer psychology, 17(1), 3-18.