What motivates rape?

Overview

Rape is a highly controversial topic and even more so when considering perpetrators’ motivation for rape. Interestingly, rape scholars have failed to provide and agree upon concrete, evidence-based, explanation of the motivating factors for rape (Bryden & Grier, 2011).The purpose of this chapter is to:

- describe the origin and relevance of the most influential motivational theories for rape

- analyse theories of rape as being sexually or non-sexually motivated

- evaluate whether studying rape motivation serves a practical function such as increasing individuals’ safety

What is rape?

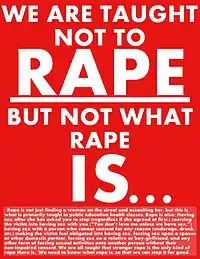

There was an upsurge in rape commentary in 1972, following Susan Brownmiller's Against our Will: Men, Women, which is still considered the most influential book on rape. Brownmiller's theories acted as the primary catalyst for bringing the topic of rape to social, legal, and academic circles from being a topic of psychiatry (Bryden & Grier, 2013; Jones, 1999). At this time, rape was considered to be a violent, sexual attack on a woman against her will. The limitations of this definition was soon evident as researchers found data on female sex offenders, and explored crime scene actions, which all implied that rape does not simply victimise women or that it is solely sex-driven (Fisher & Pina, 2013; Jamel, 2014).

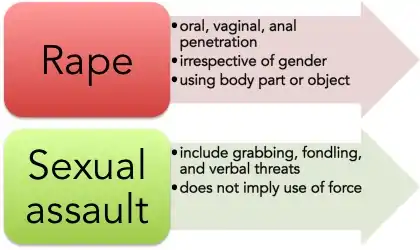

The Rape Abuse and Incest National Network currently defines rape as any oral, vaginal, anal penetration that is forced upon another, irrespective of the victim's sex or sexual orientation, using any body part or object (Aronowitz, Lambert, & Davidoff, 2012). Therefore, any individual can potentially be prey to rape, though, statistically most rapists are found to be men and most rape victims are women. Thus, this chapter focuses on male on female rape due to its higher prevalence and availability of research data.

Figure 1 clarifies the differences between sexual assault and rape (Bureau of Justice, 2015).

Rape in this day and age seems like a too-frequent crime. According to the Uniform Crime Reports, there were an estimated 79,770 rapes in the United States and the rate of rape was 25.2 per 100,000 inhabitants (UCR, 2013). However, rape is under reported for numerous reasons such as social stigma, ineffective law enforcement, discriminatory laws, and patriarchal cultures which tend to subjugate women and/or normalises their victimisation ("What statistics don't tell", 2014).

Rape motivations

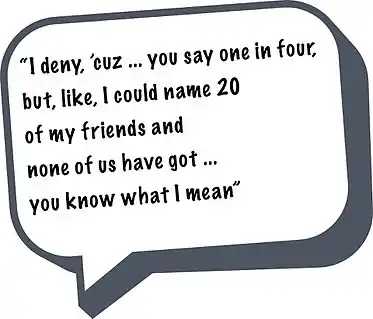

This quote highlights the contradictions and disagreements that abound in rape theory literature. This section briefly describes the origin of the most influential theories of rape motivation, leading into the discussion of which theories are most relevant to understanding rape motivations.

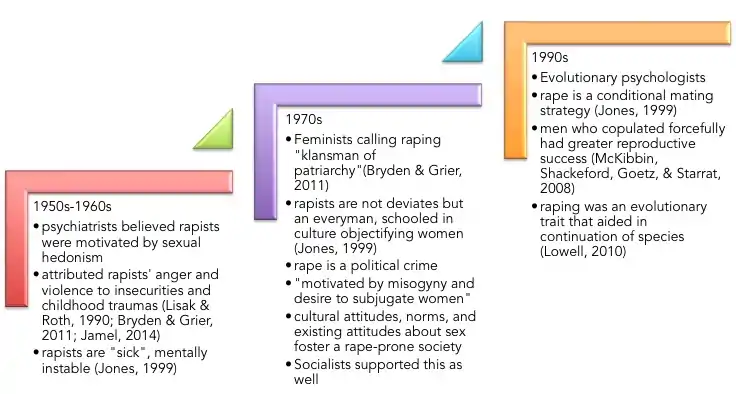

Early origins

Scholarly exploration of rapist motivations began in the 1950s and 1960s. The Figure 2 timeline highlights the key points of these theories.

Though the evolutionary theories have gained much support, they cannot explain several statistical outliers such as victimisation of men by women, victimisation of men by men, intense violence and sometimes resultant death in rapes, and the rapes of children (Strickland, 2015; Jamel, 2014; Fisher & Pina, 2013). Furthermore, it also fails to explain how, if rape is a product of natural selection, why all men are not rapists (Lowell, 2010).

Motivational theories

Due to the nature of the act, rape undoubtedly implies a certain degree of sexual motivation (Hegeman & Meikle, 1980). However, assuming that rape is solely sex-driven, is more of a myth than an empirical finding. Believing in myths such as that rape is an act of uncontrollable lust, or all rapists are deviants, can encourage victim-blaming, and inhibit the reporting of rape and hence the conviction of rapists (Hegeman & Meikle, 1980). Therefore, it is necessary to demystify the motivational aspects of rape.

|

The psychological approach to rape suggests that rape motivations can be sexual (although this can be of deviant nature in how they are gratified), power-driven, aggression-driven or a combination of motives, though the principle motivations may differ in individuals (Hegeman & Meikle, 1980). |

There has been considerable consistency in some psychodynamic patterns and principle motives that have been attributed to rapists which suggests that rape begins with the offender’s psychological needs and an unstable personality development (Hegeman & Meikle, 1980; Jamel, 2014; Lisak & Roth, 1990, Lisak, 2011; Jones, 1999; Bryden & Grier, 2011).

Groth and colleagues suggested that power and anger are the dominant motivations in rape, and rape has little to do with sex and lust (Jamel, 2014). Groth theoretically defined rape as “sexual behaviour in the primary service of nonsexual needs” and proposed a modified definition of sexual deviance as “sexuality (used) to express needs or wishes that are not primarily sexual in nature and that jeopardise the physical or psychological safety of others” (Hegeman & Meikle, 1980, p. 361).

Furthermore, he suggested that rape is a manifestation of built up anger and therefore is a pseudo-sexual act associated with control, dominance, status, hostility, and sex is only used to achieve these psychological needs (Groth & Birnbaum, 1979; Horrocks, 2010). He proposed this through clinical observation that the majority of rapes demonstrate an unnecessary level of violence and force and, for that reason, the amount of aggression implies that sex is not the sole purpose of rape, and that the sexual nature of the act is more to channel the rapist’s emotions of power, anger, and need for dominance (Groth & Birnbaum, 1979; Jamel, 2014). For example, statistics revealed that 40% of rapes have used more violence than was necessary to commit the crime (Hegeman & Miekle, 1980). Due to this, the link between aggression and sex have been extensively studied.

Rapist typologies

In 1979, Groth identified shortcomings in existing rape typologies which considered sexual motives as the primary basis and differentiating rapes on either the modus operandus (MO), or patterns of hostility, and performed factor analysis to differentiate rapists and their motives (Groth & Birnbaum, 1979).The ensuing results showed a hierarchical relationship between three factors: anger, power, and sex, where, anger and power were found to be factors with highest rankings, and sex was used as means to express the two. Subsequently, Groth published a typology of rapists, in which he dichotomised rapists by their principle underlying psychological determinant as being either anger or power (Lisak, 2011).

Rapists in the “power” category are driven by a psychological need to dominate, and avoid being dominated and they are generally less violent than anger rapists. The power rapist has been shown to threaten with weapon use, instead of brutalising, in order to make his victim achieve submission, which in turn gives the rapist a sense of pseudo-intimacy (Jamel, 2014). Furthermore, the act becomes pleasurable for the offender when the victim feels threatened enough to comply with his every desire, thus fuelling the rapist’s sense of control over the victim. This type of rapist uses violence to achieve a sense of masculinity, and uses rape to negate feelings of sexual and/or masculine inadequacy and become a dominant being (Bryden & Grier, 2011; Lisak & Roth, 1990; Jamel, 2014). Groth delineated the “power” categories into the power-assertive rapist and the power-reassurance rapist.

- "right" to have intercourse with any woman he desires

- rape act asserts his dominion and his masculinity

Power-reassurance rapist

- needs to dismiss his feelings of inadequacy and reaffirm his sense of manliness

(Jamel, 2014)

In contrast, the anger rapist is motivated by hostility and resentment towards women and also shows proclivity to inflicting undue violence on the victim during the rape. The anger rapist is motivated by revenge and retaliates for a perceived or real rejection by women and can also display sadistical enjoyment of the victim’s suffering (Horrocks, 2010; Jamel, 2014). This type of rapist uses violence to express anger, by attacking in the most degrading manner. He is characterised by a complete loss of control before and during the act, and the anger rapist rarely knows the victim. Groth categorised the "anger" rapist into the anger retaliation rapist, and the anger-excitation rapist.

- driven by revenge, rage, and hostility

- retaliates to the perceived or real rejections from women by raping

Anger-excitation rapist

- achieves sadistic thrill

- excitation by the act of rape and physical suffering of the victim

The third less common type of rapist is the sadistic rapist, who achieves sexual gratification by inflicting pain on the victim (Lisak, 2011). These rapes are generally the most violent, as the sadistic rapist will often torture his victims or perform ritualistic acts such as cutting hair, skin, nails, or washing the body. Furthermore, these rapists generally have a type of victim and their victims tend to be be similar in either occupation or appearance or both. These rapists tend to show high recidivism rates and the majority of sadistic rapists kill their victims (Jamel, 2014).

These taxonomies identified by Groth have survived the course of time and have been the foundation for more refined rape typologies which have shown similar underlying motives, and helped to identify developmental antecedents of rape (Lisak, 2011).

|

Watch an online powerpoint show on rapist typologies to further your understanding. |

Rapist characteristics

It is vital that characteristics and personalities of incarcerated rapists are explored in order to prevent rapes, identify risks, and use appropriate referrals. Though used interchangeably by some researchers, “proving masculinity”, is disparate from dominance, power, and control over women (Bryden & Grier, 2011). This characteristic is readily observable in male behaviour, as men tend to be more domineering, violent, and daring in general. Several studies have demonstrated correlations between rape and macho attitudes. Additionally, there are correlations between dominance and sexual aggression. Other findings demonstrate that sexually aggressive men are less empathetic, their level of intimacy in relationships are lower, and these men are approve of assertive behaviour even in non-sexual, non-violent contexts. Conclusions drawn from these studies imply that rapists are insecure, defensive, hypersensitive, and hostile (Bryden & Grier, 2011; Hegeman & Meikle, 1980; Jamel, 2014). They are also more likely to hold false or distorted beliefs about rape, support the use of force in relationships, and see relationships as being fundamentally exploitative (Bryden & Grier, 2011).

Risk factors

One of the primary precursors of rape is an history of childhood abuse. Furthermore, sexual abuse, physical abuse, and neglect during childhood has also been more prevalent in lives of sexual offenders, as compared to non-offenders (Lisak, 2011; Lisak & Roth, 1990). Almost all rapists reported negative relationships with their fathers, and this correlated strongly with their scores on hostility towards women, dominance, sex role stereotyping, and underlying power (Lisak & Roth, 1990). Additionally, findings from literature on juvenile delinquency has allowed researchers to draw several parallels such as a link between inadequate fathering and sexual aggression, and that inadequate fathering results in child developing an insecure masculine identification which is compensated by hypermasculine behaviour in later years (Lisak, 2011).

Research about the motivating factors has been based on studies of incarcerated rapists, since it was not until recently researchers realised that they could study non-incarcerated rapists (Lisak, 2008). Rape theorists discovered that these men did not view themselves as rapists and therefore could gather more accurate data from them.

Undetected rapists were found to beː

- more hostile

- feel need to dominate women more strongly

- more impulsive and less disinhibited in their behaviour

- more hypermasculine

- more anti-social

- less emphatic

- also showed a past history of childhood abuse

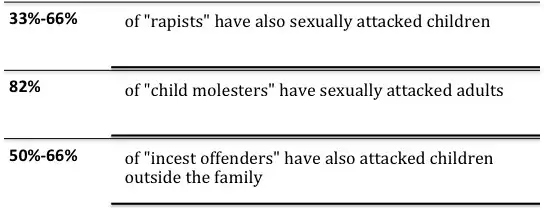

Serial offending, recidivism, cross-over offending

In-depth studies of incarcerated rapists have revealed that, although the rapist is typically convicted on a single account of rape, in reality, the average rapist has had many victims. Furthermore, research from sex-offender management programs have revealed that most offenders have a lengthy past history of sexual offences, sometimes beginning in adolescence and continuing for several decades (Bryden & Grier, 2011; Lisak, 2011). This leads into a discussion of whether the juvenile justice system is effective in dealing with adolescent sexual offences.

Another associated phenomenon that researchers have recently noted, is cross-over offending, which brings to question the efficacy of using labels such as “rapist”, “child molester”, “incest offender” since there has been substantial evidence which shows that these offenders are not strictly adhering to a type of victim (Lisak, 2011)

Are these labels effective?

![]()

Real world applications

Why do rapists' motives matter?

An understanding of motives matter because it enables us to predict behaviour. Post-release recidivism of convicted rapists is a legitimate concern. In trying to reduce this, some countries have authorised use of chemical castration, which is use of an anti-androgen substance to reduce testosterone levels (Bryden & Grier, 2011). This, and the debate on banning pornography and reducing sexual objectification of women in media is discussed in the table below.

| Popular beliefs about reducing rape and rape recidivism | Arguments & Evidence |

|---|---|

| Performing chemical castration |

|

| Increase jail time |

|

| Banning pornography |

|

| Sexual objectification of women in media |

|

Although proponents of motivational theories put forth several new insights about rape-prevention policies, the lack of solid empirical evidence makes change in courts and legislation almost impossible (Bryden & Grier, 2011).

Finally, if motive is viewed as a goal, then sexual gratification may be the most common goal of all, however, whether it leads to rape is almost always determined by additional causes such as power, aggression, in combination with developmental antecedents, as well as social leniency, hyper-masculinity, gender equalities, media depiction, sex roles, and so on. Strategies to reducing these motivational factors are likely to result in reductions of rape occurrence.

What does this imply for the community and society?

The implications for rape motivation study lie in the similarities between undetected rapists and incarcerated rapists. These two groups display the same motivational matrix of anger, dominance, hostility, hyper-masculinity, impulsiveness and antisocial tendencies, as well as having same developmental antecedents (Lisak & Roth, 1990). However, most rape and sexual assaults that occur in universities, parties, and dorms, are written off as the result of a “decent” boy who had too much to drink and there was some miscommunication otherwise he would have never done such a thing (Lisak, 2011). It is not impossible that, in some instances this may very well be accurate, but the majority of these rapes are not so benign. These misconceptions pervade authorities' attempts to prevent such incidences by attempting to persuade men from not raping via traditional rape prevention programs, which have sometimes resulted in worsening of attitudes (Hillenbrand-Gunn, Heppner, Mauch, & Park, 2010; Rich, Utley, Janke, & Moldoveanu, 2010). However, given what is now known about rapist motivations, it is highly unlikely that a serial offender’s behaviour will change by mere persuasion. Past and current research both highlight how, even after incarceration and intensive sex-offender correction programs, rape recidivism rates are still high (Bryden & Grier, 2011; Lisak, 2011; Jones, 1999).

Self defense

A potential campaign would be to encourage women to learn self-defense. A review of rape resistance literature showed that women who used non-forceful tactics (e.g., pleading) were raped 96% of the time and, in contrast rape attempts where women physically resisted dropped 14% to 45% (Morrison, 2005). Another sobering fact is that, although women rate rape as a serious offense, they do not enrol in self-defence classes. Beliefs like those shown in Figure 5 pervade the society and increase women’s perception of invulnerability which places them at a greater risk of sexual assault, as people adhering to such myths end up denying the existence of the threat (Morrison, 2005, p. 240).

|

Save yourself from rape by learning these quick defense tactics |

Bystander education

Bystander education has been proven to be effective (Lisak, 2011). Bystander education involves both men and women and empowers them to notice risk around them and respond constructively (Katz, Olin, Herman, Dubois, 2013). Research demonstrates that these education classes can effectively promote safety on university campus by cultivating prosocial attitudes and behaviours and make people more likely to intervene in high-risk situations (Katz et al., 2013). Research suggests that when men are made aware of how rape impacts them as partners, brothers, friends of women who are the victims, the misguided attitudes about rape and rape prevalence can begin to change (Morrison, 2005).

|

Try out "bystander intervention" for yourselfǃ |

Test your knowledge

|

|

Conclusion

This key points from chapter are that:

- Rape is not a single motive driven crime.

- Rape motivators: power, anger, sex were found to be the most comprehensive, and are well-supported by literature

- Assigning a single motive to rape limits an individual's safety, increases victim-blaming, and prevents development of appropriate interventions

- Studying rape motivation helps us to:

- Identify sub-groups at risk for committing rape and sexual aggression

- Helps frame interventions

- Help people avoid becoming victims of rape and sexual assault

Finally, though it is vital that future prevention campaigns keep educating and empowering women, it is critical that it is done in a manner as to not take away the social freedom of women. Thus, future campaigns should focus on involving both men and women, and demonstrating to them the importance and efficacy of working together to reduce rape incidences.

See also

References

Aubrey, J. S., Hopper, K. M., & Mbure, W. G. (2011). Check that body! The effects of sexually objectifying music videos on college men's sexual beliefs. Journal Of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 55(3), 360-379. doi:10.1080/08838151.2011.597469

Bryden, D. M., & Grier, M. M. (2011). The search for rapists’ “real” motives. Journal of Criminal Law & Criminology, 101(1), 171-278. Retrieved from http://web.b.ebscohost.com.ezproxy.canberra.edu.au/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?sid=d12aeb10-c3bc-47e8-8d1e-b8d3d7a52b46%40sessionmgr111&vid=6&hid=128

Bureau of justice statistics. (2015). Rape and sexual assault. Retrieved from http://www.bjs.gov/index.cfm?ty=tp&tid=317#terms_def

Fisher, N. L., & Pina, A. (2013). An overview of the literature on female-perpetrated adult male sexual victimization. Aggression & Violent Behavior, 18(1), 54-61 8p. doi:10.1016/j.avb.2012.10.001

Groth, A. N., & Birnbaum, H. J. (1979). Men who rape: The psychology of the offender. New York: Plenum Press.

Hegeman, N., & Meikle, S. (1980). Motives and attitudes of rapists. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science/Revue Canadienne Des Sciences du Comportement, 12(4), 359-372. doi:10.1037/h0081079

Hillenbrand-Gunn, T. L., Heppner, M. J., Mauch, P. A., & Hyun-joo, P. (2010). Men as allies: The efficacy of a high school rape prevention intervention. Journal of Counseling & Development, 88(1), 43-51. Retrieved from http://web.b.ebscohost.com.ezproxy.canberra.edu.au/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?sid=d12aeb10-c3bc-47e8-8d1e-b8d3d7a52b46%40sessionmgr111&vid=62&hid=128

Horrocks, C. (2010). The myth of the female sex offender. Undergraduate Review, 6, 100-106. Retrieved from http://vc.bridgew.edu/undergrad_rev/vol6/iss1/20

Jamel, J. (2014). An exploration of rapists' motivations as illustrated by their crime scene actions: Is the gender of the victim an influential factor?. Journal of Investigative Psychology and Offender Profiling, 11(3), 276-298. doi:10.1002/jip.1422

Jones, O. D. (1999). Sex, Culture, and the Biology of Rape: Toward Explanation and Prevention. California Law Review, 87(4), 829. Retrieved from http://web.b.ebscohost.com.ezproxy.canberra.edu.au/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?sid=d12aeb10-c3bc-47e8-8d1e-b8d3d7a52b46%40sessionmgr111&vid=17&hid=128

Katz, J., Olin, R., Herman, C., & DuBois, M. (2013). Spotting the signs: First-year college students’ responses to bystander-themed rape prevention posters. Journal of Community Psychology, 41(4), 523-529. doi:10.1002/jcop.21552

Lisak, D. (2011). Understanding the Predatory Nature of Sexual Violence. Criminal Justice Research Review, 12(6), 105-108. Retrieved from http://www.middlebury.edu/media/view/240951/original/PredatoryNature.pdf

Lisak, D., & Roth, S. (1990). Motives and psychodynamics of self-reported, unincarcerated rapists. American Journal Of Orthopsychiatry, 60(2), 268-280. doi:10.1037/h0079178

Lowell, G. (2010). A review of rape statistics, theories, and policy. Undergraduate Review, 6, 158-163. Retrieved from http://vc.bridgew.edu/undergrad_rev/vol6/iss1/29

Malamuth, N. M., & Check, J. V. (1983). Sexual arousal to rape depictions: Individual differences. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 92(1), 55-67. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.92.1

McGee, H., O’Higgins, M., Garavan, R., & Conroy, R. (2011). Rape and child sexual abuse: What beliefs persist about motives, perpetrators, and survivors?. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 26(17), 3580-3593. doi:10.1177/0886260511403762

McKibbin, W. F., Shackelford, T. K., Goetz, A. T., & Starratt, V. G. (2008). Why do men rape? An evolutionary psychological perspective. Review of General Psychology, 12(1), 86-97. doi:10.1037/1089-2680.12.1.86

Morrison, K. (2005). Motivating women and men to take protective action against rape: Examining direct and indirect persuasive fear appeals. Health Communication, 18(3), 237-256. doi:10.1207/s15327027hc1803_3

Rich, M. M. (2010). "I'd rather be doing something else:" Male resistance to rape prevention programs. Journal of Men's Studies, 18(3), 268-290. doi:10.3149/jms.1803.268

Ståhl, T., Eek, D., & Kazemi, A. (2010). Rape victim blaming as system justification: The role of gender and activation of complementary stereotypes. Social Justice Research, 23(4), 239-258. doi:10.1007/s11211-010-0117-0

Strickland, S. (2008). Female sex offenders: exploring issues of personality, trauma, and cognitive distortions. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 23(4), 474-489. doi: 10.1177/0886260507312944

U.S. Department of Justice. (2014). Uniform crime reports: Reporting rape in 2013. Retrieved from https://www.fbi.gov/about-us/cjis/ucr/recent-program-updates/reporting-rape-in-2013-revised

(2014, July 15). What statistics don’t tell. Nation (Pakistan). Retrieved from http://web.b.ebscohost.com.ezproxy.canberra.edu.au/ehost/detail/detail?sid=d12aeb10-c3bc-47e8-8d1e-b8d3d7a52b46%40sessionmgr111&vid=72&hid=128&bdata=#AN=2Z11NAT20140715.XXVIII.138.00039.2&db=n5h