What is the hedonic treadmill and how does it influence our emotional lives?

Overview

|

Emotion: A “particular state of an organism facing well defined conditions (a so-called emotional situation) which is coupled with a subjective experience and with somatic and visceral manifestations" (Doron & Parot,19911). Emotion involves a short term reaction to a specific event. |

As a child can you remember ever getting so excited for Christmas day and not being able to wait to open all your presents? Can you remember opening them and feeling overjoyed with excitement because of your brand new toy? Can you remember getting to the end of the day and feeling that the brand new toy was no longer exciting to play with? When you do finally open all your presents you do not feel as happy as you thought you would. You no longer have that intense feeling of excitement.

Have you ever had a really bad day that made you just want to cry? Can you remember expecting things to only get worse? Can you remember waking up the next day and feeling better? Although you had a bad day and expected things to get worse this feeling was only temporary. After a day or so you are back to normal and feeling fine, forgetting all about it.

It is our hedonic treadmill or set point of happiness that allows us to experience both good and bad feelings only to return to our normal state of happiness or hedonic neutrality. This chapter aims to explain the hedonic treadmill and how it influences our emotional lives. This chapter will outline both the hedonic treadmill and what is meant by emotional lives. This chapter will examine theoretical approaches to happiness in relation to the hedonic treadmill. Lastly this chapter will review evidence about how the hedonic treadmill motivates our emotional lives, how it relates to depression and examine critical views against the hedonic treadmill. After reading this chapter you should be able to understand the hedonic treadmill, our emtional lives and the role that the hedonic treamill plays in our emotional lives. You should also be able to understand how the hedonic treadmill relates to resilience and why it is we are able to 'bounce back' from negative events in our life.

Introduction

What is the Hedonic treadmill?

The idea that a persons happiness or well-being is relative to ones circumstances has been around for centuries. The hedonic treadmill was constructed by Brickman and Campbell in 1971 (Brickman et al, 1978) and is also known as the set-point theory. According to the hedonic treadmill model people temporarily experience both good and bad events that affect their happiness but quickly adapt back to equilibrium or hedonic neutrality (Diener, Lucas & Scollon, 2006). Although our lives are constantly changing, our happiness is at a relatively constant state or has what is known as its set-point (Brickman et al, 1978). Similar to a treadmill, we are constantly striving for more, only to then return to our original position on the treadmill, also known as our set point of happiness or hedonic neutrality. For example, the hedonic treadmill suggests that just because a person is wealthy does not mean that they are happier than someone who is poor. This is seen in Brickman et al's (1978) study which found that major lottery winners are not significantly happier than the control subjects. Major lottery winners also derive significantly less satisfaction from ordinary daily life activities (Brickman et al, 1978). The hedonic treadmill or set point theory is an important tool for explaining resilience. Resilience involves an interaction between both risk and protective processes that act to modify the effects of an adverse life event (Garmezy, (1985). Therefore it is a persons ability to recover from negative events (Garmezy, 1991). Resilience and the hedonic treadmill or a persons set point are correlated.

The hedonism theory suggests that there are two forms of happiness, including: Hedonia and eudaimonia (Waterman, 2007). Firstly, hedonia is the affective component of happiness. It consists of conscious feelings of pleasure and well-being (Waterman, 2007). Whereas, eudaimonia emerged from Aristotelian philosophy (Kristjansson, 2010). Aristotle defined happiness as being centred around what it means to live a good life (Ryan, Huta & Deci, 2006). Therefore, eudaimonia is a persons sense of life satisfaction regarding their life meaning (Waterman, 2007). Seligman & Royzman (2003) agree that happiness is labelled by a subjective feeling, but stated that in order to be a happy person one must maximise pleasurable feelings and minimise negative. Studies suggest that eudaimonic happiness has a strong correlation with relatedness and a personal concern for others (Haybron, 2000). However, the hedonic treadmill only functions one level of happiness being hedonia (Waterman, 2007).

What is our emotional life?

As humans we all experience a range of different emotions across certain periods of time. Firstly it is important to understand emotion. Emotion a complex idea with no universal agreed definition. A general definition of emotion identifies it as a short lived phenomena that helps us to adapt to life events (Ekman, 1992). Life is full of a number of stresses, challenges and problems. Emotions arise as a solution to these stresses, challenges and problems (Ekman, 1992). Our emotional life involves the complex range of emotions we feel throughout the entirety of our lives. Our emotions change rapidly and a number of times in one day, therefore constantly changing throughout our lifetime. For example James may feel angry and frustrated one morning because his car will not start. However at lunchtime James feels joy because as he is marking students work a number of them are of high standard. Over a period of approximately 4 hours James' emotions have changed from one side of the spectrum to the other. The emotional life is this roller-coaster of changing emotions over a persons lifetime. The emotional life is a domain that requires a unique set of competencies (Goleman & Sutherland, 1996) and those who do not have some control over their emotional life fight inner battles which effect their ability to focus (Goleman & Sutherland, 1996). This is seen in children who suffer particularly from Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (Peris, 2003). Our emotional lives are similar to a roller coaster as we all experience a number of highs, lows and varying in between stages.

Theoretical approaches

Behavioural

As Brickman et. al. (1978) suggested, a person who is rich is not necessarily happier than those who are not rich. The behavioural approach to the hedonic treadmill poses that once we experience a positive event, this experience only temporary. According to Frederick and Lowenstein (1999) the behavioural approach to the hedonic treadmill includes three types of processes. These processes include: shifting adaption levels, desensitisation and sensitisation. When there is a shift in what a person perceives as a 'neutral stimulus' but they are still sensitive to stimulus differences, shifting adaption levels occur (Frederick & Lowenstein, 1999). An example of this is when someone believes a new job will significantly improve their life. When they obtain the wanted job they are initially happier about getting the job. They then become accustomed to the new job and return to feeling dull at work. They have returned to their hedonic neutrality or set happiness. However, when the employee receives a change in areas for their new job they are still pleased. The shifting adaption levels mean that a persons happiness is temporarily increased by a particular event. After time this event no longer has the same effect and a persons happiness returns to normal. Desensitisation decreases sensitivity in general causing a person to be less sensitive to change (Frederick & Lowenstein, 1999). For example, someone who has lived in an outback rural area may become desensitised to the death of animals as this is a regular occurrence on large farms. Later in life when needing to put down a pet they will find this less emotionally upsetting than others due to their desensitisation. Desensitisation is one example to why people who have lived in war torn areas tend to find the loss of close ones less impacting because they have become desensitised to devastation and loss. For example, someone who was a child in Germany during World War II will not tend be as effected by the loss of a family member than people who did not grow up in a war torn area. Thirdly, continuous exposure to a stimulus may increase hedonic response, resulting in sensitisation (Frederick & Lowenstein, 1999). For example increased pleasure of chocolate makes a person want to go back for more. These three processes play a key role in the behavioural approach to the hedonic treadmill.

Biological

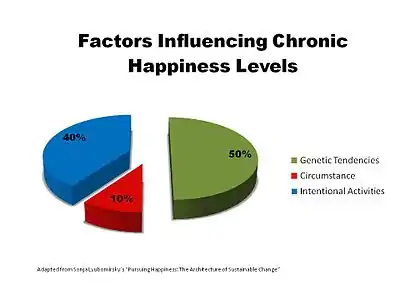

According to the biological approach to happiness, an individuals happiness is genetically influenced. Studies have found a correlation between a persons happiness and their levels of dopamine and serotonin (Ebstein et al, 1996). This suggests that an individuals happiness is inherited through their genes as studies have found that genes play a major role in regulating levels of dopamine and serotonin (Ebstein et al, 1996).Studies of over 3,000 identical and fraternal twins revealed that genetically identical twins showed similar levels of happiness, even when raised apart from each other (Lykken & Tellegen, 1996). The reported well-being of someone's identical twin has been found to be a better predictor of someone's happiness than income, educational achievement or social status (Lykken & Tellegen, 1996). These studies of twins suggest that a persons happiness is inherited in their genes. Genes play a important role in understanding an individual. Similarly to the hedonic treadmill people also have a biologically determined weight. This set-point theory argues that an individuals biologically determined weight is set by genetics at birth or shortly after (Powley & Keesey, 1970). The biological approach to happiness is the most significant approach to the hedonic treadmill as it suggests that a persons baseline level is biologically determined (Brickman et al, 1978).

How does the hedonic treadmill influence our emotional lives?

The hedonic treadmill plays an important role in our emotional lives. As we strive to increase our happiness, after positive events occur, a persons happiness will return to their personal set point of happiness (Brickman et al, 1978) . Alternatively we also experience negative events in our lives which makes a persons happiness level decrease. The hedonic treadmill also works as a form of resilience returning a persons happiness to their set point of happiness (Masten, 2009). This is important because, without resilience or this return to our set point of a happiness, several negative life events may cause a person to feel extremely dull and depressed all the time (Masten, 2009). Imagine the embarrassment you feel when you fall over in front of your friends, this feeling of embarrassment decreases a persons level of happiness. Imagine the next day you go to work feeling dull, only to be fired. This in turn also drops a persons level of happiness. Now imagine that your happiness level were not to increase until a positive event occurred. This 'bouncing back' from negative events that have decreased happiness is important for a persons well-being.

Moods and emotions

Both moods and emotions play a role in how we feel. Our emotions are short lived responses to a specific significant event in our lives (Ekman, 1992). Whereas moods arise from ill-defined sources that are often unknown and are long lived (Goldsmith, 1994). Davidson (1994) found that our emotions influence our behaviours whereas our moods influence our cognition's . Our emotions change more rapidly than moods as our events change (Ekman, 1992). It is these positive or negative events which change our emotions. As a result, our happiness levels alter with our emotions. This is where the hedonic treadmill comes in.

How the hedonic treadmill influences our emotional lives

The hedonic treadmill influences ou,r emotional lives by controlling our baseline happiness and despite life events we always return to this baseline. The most famous study involving the hedonic treadmill is Brickmans (1978) study. Brickman interviewed both lottery winners and paraplegics. This study found that years after winning the lottery people were no happier than they were before winning the lottery. The large gain of money from the lottery winners had no effect on peoples baseline or set happiness. These results were also found for paraplegics. years after the accident paraplegics reported similar levels of happiness to before the accident. Paraplegics did experience a significant decline in happiness as a result of the accident. They then returned to their baseline happiness years after the accident. Similarly, Silver's (1982) study of the effects of a traumatic accident causing spinal injury on a persons baseline level of happiness. Silver followed participants over 8 weeks. After the first week participants showed greater levels of negative emotions than positive. In the eighth week after their accident participants showed greater levels of positive emotions than negative. These studies reveal that despite the persons situation being positive or negative, and the direction of emotions being either positive or negative, our happiness or emotions always return to the baseline. Therefore the hedonic treadmill influences our emotional lives by allowing our emotions to be temporary to our situation.

Headly and Wearing (1989) ran a longitudinal study where participants were followed over a period of 8 years. They made a number of variations to the hedonic treadmill theory. Headly and Wearing (1989) proposed that similar to the hedonic treadmill a persons baseline happiness is within the positive range and also that people return to differing baselines depending on their personalities. This study found that happy people were more likely than unhappy people to to experience good events and therefore argued that a persons baseline is due to an individuals likelihood to experience certain affect-inducing events (Headly & Wearing, 1989). This modification of the hedonic treadmill is important as it states that peoples baseline happiness varies depending on the persons personality. Some researchers suggest that trying to be happier is a pointless battle, similar to trying to be taller (Lykken & Tellegen, 1996). This is because the hedonic treadmill continues to draw us back to our set point of happiness.

Hedonic treadmill and depression

In modern society depression has become a large psychological issue. Depression is one of the most impacting mood disorders. Depression is a state of low mood that affects a persons behaviour, thoughts, feelings and sense of well-being (Salmans & Sandra, 1997). The hedonic treadmill is a useful tool in clinical psychology to help patients return to their hedonic set point when negative events happen. This is important for patients with depression and post traumatic stress disorder who struggle to return to their hedonic set point. Determining when someone is mentally distant from their personal set point and what causes these changes are helpful in treating a number of conditions, specifically depression (Sheldon, Lyubomirsky & Sonja, 2006). Clinical psychologists work with patients to recover from a depressive episode and return to their hedonic set point more quickly (Sheldon, Lyubomirsky & Sonja, 2006).One treatment provides patients with different altruristic activities, as acts of kindness to promote a persons long-term well-being. On top of this it is important that patients understand the hedonic treadmill and that long-term happiness is relatively stable. This helps to ease anxiety over strong impacting events (Sheldon, Lyubomirsky & Sonja, 2006). This treatment uses a persons hedonic treadmill to restore them to their set point of happiness.

Hedonic adaptation also applies to resilience research. Resilience is a class of phenomena characterised by patterns of good outcomes in the context of serious risk or threat (Masten, 2001). Therefore resilience is a persons ability to remain at their hedonic set point while experiencing negative events. A number of factors that contribute towards a person being resilient includ: positive attachment relationships, positive self perceptions, self-regulatory skills and a positive outlook on life (Masten, 2009). Resilience or a persons ability to 'bounce back' from negative events is also important for patients with depression. Patients with depression tend to struggle with resilience to negative events, therefore the use of the hedonic treadmill on resilience studies is important.

Critical views

There is significant evidence to support the idea of the hedonic treadmill or a persons biological set happiness. Like all theories the hedonic treadmill also has it downfalls. The biggest limitation of the hedonic treadmill is that it does not allow for a persons overall happiness to increase despite individual and societal efforts. There is an increasing amount of evidence that with the use of appropriate measures and specific interventions aimed at fostering strengths and virtues that happiness can be increased (Narrish & Vella-Brodrick, 2008). Diener, Lucas & Scollon (2006) found that different types of well-being change at different rates. Evidence also suggests that individuals adaption rates vary and although adaption may proceed slowly over time, in some cases the process in never complete (Diener, Lucas, & Scollon, 2006). Headly and Wearings's (1989) study could not explain if people always return to the same baseline or if new ones are created.

Alternative views to the hedonic treadmill include desire theory, objective list theory and authentic happiness theory. Desire theory suggests that people experience a sense of happiness as a result of obtaining what they want or desire (Seligman & Royzman, 2003). These wants and desires are subjective. For example an individual is happier after receiving a book they have wanted. According to this theory if a person is able to fulfil their desires they may experience a negative affect, but still be considered happy. Objective theory proposes that happiness results from large achievements such as lifetime goals (Seligman & Royzman, 2003). These lifetime goals could include events such as obtaining a doctorate degree. Finally, the authentic happiness theory suggests that three types of happiness which incorporate hedonism, desire and objective list theories (Seligman & Royzman, 2003). This includes pleasant life, good life and meaningful life (Seligman & Royzman, 2003). Authentic happiness results in satisfying a persons entire life by satisfying all areas of happiness.

Another alternative view to the hedonic treadmill accepts that a persons happiness is stable and heritable, it is not genetically predetermined and can be altered by ones behaviour (Byrnes & Strohminger, 2005). Various controllable life factors have been shown to predict high happiness (Byrnes & Strohminger, 2005). Placebo studies have shown that antidepressant medications are effective in treating depression and psychotherapy such as cognitive therapy teach a person to control negative thoughts (Byrnes & Strohminger, 2005). Despite the use of antidepressants by those who do not suffer from depression not being advisable it is suggested that people with average happiness could increase their overall life happiness by using cognitive therapy to control negative thoughts (Byrnes & Strohminger, 2005). People dismiss the hedonic treadmill for a number of reasons. The biggest critic of the hedonic treadmill is due to the fact it does not allow people to increase their happiness despite their efforts.

Conclusion

The hedonic treadmill suggests that each individual has a biologically determined set happiness that is stable over their lifetime. Studies of lottery winners and paraplegics reveal that despite a person experiencing significant positive or negative life events, over time they return to their set happiness. This influences an individuals emotional life because it allows them to experience both positive and negative events. The hedonic treadmill allows individuals to experience positive experiences such as pay rises, engagements, marriage, births and so on . On the other hand it also allow people to experience negative events such as loss of a job, accidents, death of family or close ones and more . After both positive and negative events we return to our baseline happiness allowing us to continue to experience positive and negative events, in our emotional lives. The hedonic treadmill poses as a tool to help those who suffer from depression to return to their set happiness as fast as possible. The downside of the hedonic treadmill is that no matter how hard an individual or society tries to increase their happiness, the hedonic treadmill suggests that a persons biological set happiness does not vary significantly over ones lifetime. Similar to a roller-coaster, our emotional lives are constantly moving and changing, similar to the hedonic treadmill we continue to strive for more and once there we return to our original position.

- Take home message

Our emotional lives constantly change, this is because the hedonic treadmill allows a person to experience positive and negative events, only to return to their biologically set happiness. Despite our negative life events the hedonic treadmill allows a person to be resilient and bounce back to their set happiness. Therefore there are two important message to take away from this book chapter:

- receiving gifts and achieving small goals can make one immediately happy but it does not always bring long-term happiness, and

- remember that a bad day will always get better no matter how much you think it won't.

See also

- Change and happiness (Book chapter, 2011)

- Depression (Book chapter, 2010)

- Happiness (Book chapter, 2011)

- Chocolate and mood (Book chapter, 2014)

References

Byrnes, S., & Strohminger, N. (2005). The Hedonic Treadmill. Science B62, University of.

Davidson, K. J. (1994). Un emotion, mood, and related affective constructs. In P. Ekman & R. N. Davidson (Eds) The nature of emotion: Fundamental questions. (pp.51-55). New York: Oxford University Press.

Diener, E., Lucas, R. E., & Scollon, C. (2006). Beyond the hedonic treadmill: Revising the adaption theory of well-being. American Psychologist, 61(4), 305-314. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.61.4.305

Doron, R., Parot, F. (1991). Dictionnaire de psychologie. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France

Ebstein, R. P., et al. (1996). Dopamine D4 receptor (D4DR) exon III polymorphism associated with the human personality trait of Novelty Seeking. Nature Genetics, 12, 78-80

Ekman, P. (1992). An argument for basic emotions. Cognitive and Emotion, 6, 169-200

Frederick., & Lowenstein.(1999) Hedonic Adaptation. Well-being: The foundations of hedonic psychology, 302-329

Garmezy, N. (1991). Resilience in children's adaptation to negative life events and stressed environments. Pediatric Annals, 20, pp. 459–466

Gilbert, D. T., Pinel, E. C., Wilson, T. D., Blumberg, S. J., & Wheatley, T. P. (1998). Immune neglect: A source of durability bias in affective forecasting. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75(3), 617–638.

Goleman, D., & Sutherland, S. (1996). Emotional intelligence: Why it can matter more than IQ. London: Bloomsbury.

Goldsmith, H. H. (1994). Parsing the emotional domain from a developmental perspective. In P. Ekman & R. J. Davidson (Eds) The nature of emotion: Fundamental questions. (pp.68-73). New York: Oxford University Press.

Haybron, D.M. (2000). Two philosophical problems in the study of happiness. The Journal of Happiness Studies, 1(2), 207-225.

Headly, B., & Wearing, A. (1989). Personality, life events, and subjective well-being: Toward a dynamic equilibrium model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57, 731-739

Krisjansson, K. (2010). Positive psychology, happiness and virtue: The troublesome conceptual issues. Review of General Psychology, 14(4), 296-310.

Lykken, D., & Tellegen, A. (1996) Happiness is a stochastic phenomenon. Psychological Science, 7, 186-189

Masten, A. S., Cutuli, J. J., Herbers, J. E., & Reed, M.-G. J. (2009). Resilience in development. In C. R. Snyder & S. J. Lopez (Eds.), Oxford Handbook of Positive Psychology, 2nd ed. (pp. 117 - 131). New York: Oxford University Press.

Masten, A. S. (2001). Ordinary magic: Resilience processes in development. American Psychologist, 56(3), 227-238. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.56.3.227

Norrish, J., & Vella-Brodrick, D. (2008). Is the Study of Happiness a Worthy Scientific Pursuit?. Social Indicators Research, 87(3), 393-407.

Peris, T. P. (2003). Family dynamics and preadolescent girls with ADHD: the relationship between expressed emotion, ADHD symptomatology, and comorbid disruptive behavior. Journal Of Child Psychology & Psychiatry & Allied Disciplines, 44(8), 1177-1190.

Powley, T. L, & Keesey, R. E. (197). Relationship of body weight to the lateral hypothalamus feeding syndrome. Journal of Comparative and Clinical Psychology, 70, 25-36

Ryan, R.M., Huta, V., & Deci, E.L. (2006). Living well: A self-determination theory perspective on eudaimonia. Journal of Happiness Studies, 9(1), 139-170.

Salmans, Sandra (1997). Depression: Questions You Have – Answers You Need. People's Medical Society. ISBN 978-1-882606-14-6.

Seligman, M. & Royzman, E. (2003). Happiness: the three traditional theories. Retrieved from http://pq.2004.tripod.com/happiness_three_traditional_theories.pdf

Sheldon, K. M.; Lyubomirsky, & Sonja (2006). "Achieving Sustainable Gains in Happiness: Change Your Actions Not Your Circumstances". Journal of Happiness Studies, 7, 55–86. doi:10.1007/s10902-005-0868-8.

Silver (1982). Coping with an undesirable life event: A study of early reactions to physical disability. Northwestern University

Waterman, A. (2007). “On the Importance of Distinguishing Hedonia and Eudaimonia When Contemplating the Hedonic Treadmill.” American Psychologist, September 2007, Vol. 62, No. 6, 612-613.