Why do we cry? When is it good to cry?

![]()

Overview

| “ | "Life is an onion - you peel it year by year and sometimes cry." (Carl Sandburg, Remembrance Rock) |

” |

The first thing we do after being born is to cry, and the last thing we do when people die is to cry. Crying is a normal part of growing up as well. Crying makes us stronger and more mature through our life span. Thus, crying seems important for us. However, how many of you understand crying correctly? Do you really understand why we cry? It seems that many people do not know exactly what crying is about despite its importance. If we understand about the purpose of crying and its benefits, crying can be more helpful for you in terms of your physical and psychological health. This chapter will mainly focus on the reasons of crying and how beneficial crying is for us through psychological theories.

Definition of crying

Charles Darwin (1872) suggested that crying is a natural human behaviour that is distinct from animal crying. Botelho (1964) said that crying is a typical way for human to express their emotion. Crying is defined as shedding of tears. "Sobbing, weeping, wailing, whimpering, bawling, or blubbering" are all different expressions of crying. In physiological terms, Patel (1993) defined crying is "a complex secretomotor phenomenon characterized by the shedding of tears from the lacrimal apparatus, without any irritation of the ocular structures".

Why do we cry?After scientists discovered that tears are generated by our lacrimal glands, they found that there are three types of tears (see Table 1; Keedle, 2010). There are a number of reasons why we cry: (1) Physiological reasons, (2) Evolutionary reasons, (3) Psychological or emotional reasons, and (4) Cultural and social reasons. In this part, we will explore the multidimensional reasons of crying.

Physiological reasons Lachrymal glands Reductionist theories Reductionists take a physiological approach to explain crying. When you cry, tears roll down your face. Flicking eyes or similarly, closing eyes very tightly would stimulate the lachrymal glands and that causes to bring tears out (Darwin, 1872; Dixon, 2013). The primary reason for crying is to protect eyes. Basal tears protect the surface of the eye by lubricating the surface of the eye (Darwin, 1872). According to Montague (1959), the major reason for crying is to prevent eyes from drying. Sobbing leads us to inhale and exhale huge amount of air quickly that makes the nose and throat dry. To protect the nose and throat to be dried, tears would keep them moist. He suggested that tears also prevent eye from infections. The lacrimal fluid, which is basically the same as tears, contains the antibacterial enzyme lysozymes that protect eyes to be free from infections (Montague, 1959). Evolutionary reasons.jpg.webp) A cartoon depicting Charles Darwin as an ape. Crying plays an important role for humans to survive (Darwin, 1872). First, when we are in pain, our body alerts us by crying. When we are under stress or pain, we can experience some common reactions to stress such as sweating and having increased heart rate. Crying relieves those physical responses (APS, 2008). Second, crying can handicap aggressive or defensive actions from attackers. Emotional tears increase the expression of sadness that can handicap aggressive or defensive actions (Hasson, 2009). Finally, crying helps build relationships and a need for attachment which are key for survival (Hasson, 2009). Emotional (Psychological) reasonsCharles Darwin suggested that animals cry emotionally, however, modern scientists argue that human beings are the only animal capable of crying emotionally. Cathartic theories, two-factor theory, and learned helplessness theory help to explain when emotional tears are released and why.

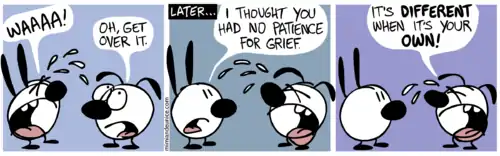

Grief is different when it's your own.  The families of North and South Koreans are crying for the joy of reuniting. Crying for joy becomes special when people overcome stressful events and achieve a happy ending. Table 2. Reasons for crying based on learned helplessness theory Based on Miceli, M & Castelfranchi, C. (2003). Crying: Discussing its basic reasons and uses. New Ideas in Psychology, 21, 247-273.

Social reasonsHave you ever cried because of others? You must have cried at least once in your life because of others. Frey and Langseth's 1985 study (as cited in Vingerhoets, Cornelius, Van Heck, & Becht, 2000, p. 363) found that 40% of participants in their study cried for social reasons. Similarly, Bylsma and his colleagues (2008) examined a cross-cultural study about types of antecedents reported for the most recent crying episode. Conflict was the third most important attribution for crying, with 13.3% of the total sample (4,249 respondents). Thus, the social contexts of crying seem important. Crying in a social setting can be explained differently for infants and adults. Infants cry for communicating and being attached with their caregivers. The reasons for adult crying are broader and include interpersonal skills, communication with others, bonds, and relationships.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Take Home Message

Crying is not only for protecting eyes and emotional responses, but also for communication and building relationships. |

|

Activity 2: for the people who can't cry - Take the "No Cry" challenge on YouTube

|

When is it good to cry?Why we cry was discussed in the previous section. This section explores when we normally cry, how often we cry, when crying is good for us, and when crying is not good for us.  We cry more often before we go to bed, than during the day. When do we normally cry?Think about last time when you cried. Did you cry in the night or during the day? You might cry in the night. How do I know it? It is because researchers suggest that people cry more often in the night time than during the day. According to Bylsma, Vingerhoets and Rottenberg (2008), most people cry in the late evening between 10 pm and midnight. Frey (1985) found that women cry more often between 7 pm and 10 pm than between 9 am and 7 pm. Furthermore, the frequency of crying (only for women) increases between 11 pm and 4 am (Vingerhoets, Sanders & Kuper, 1997). Why do we more likely to cry in the night than during the day? Researchers found that there are several factors that may cause people to cry during the night time. First, the threshold for crying may be lowered in the night. We are tired and feel safe at home in the night. As a result, it may be easier for us to cry in the night. Second, people might have more conflicts with their family members in the night than during the day. Finally, night time is good for us to reflect our emotional events that happened during the day (Vingerhoets, Cornelius, Van Heck & Becht, 2000). How often do we cry? (Frequency of crying)

When is it good to cry?

|

When is it not good to cry?

|

|

Take Home Message

Not all cries make you feel better. But, it's sometimes good to cry. |

Have you ever experienced embarrassing moments because you cried in inappropriate situations or in public? For example, when you cried in class or meeting with your boss. Here are some ways to keep yourself from crying until you feel more comfortable doing so.

There are 4 strategies to stop yourself from crying include:

- Physically stopping yourself from crying

- Focus on your breathing

- Move your eyes to control your tears

- Distract yourself with a physical movement

- Remove the lump in your throat

- Mentally stopping yourself from crying

- Think of something that you can focus entirely on<

- Think of something funny

- Remind yourself that you are a strong individual

- Distract yourself by engaging in something else

- Getting away with a few tears

- Blame your tears on something else

- Dry your tears discreetly

- Remove yourself from the situation

- Letting it out and moving on

- Let yourself cry

- Examine why you want to cry or are crying

- write in a journal or diary

- Talk to someone

- Distract yourself with things you love

- Stay positive

Note. Quoted from (wikihow) http://www.wikihow.com/Stop-Yourself-from-Crying

|

Application: crying as a therapeutic purpose

|

Critique of current theories and research: limitations of the measurementCrying is a fascinating topic to study out of all emotions. Crying studies have been conducted by researchers from different backgrounds such as physiology, biology, sociology and psychology. The current theories and research have been helpful for us to improve our knowledge about crying, as well as, improve our mental health. However, a major challenge for crying research is measurement. Most of crying studies are dependent on self-report measurement. However, self-report measurement may not be valid sometimes. Participants may lie because they may be too embarrassed to provide their private details such as when they cried last time and why. To decrease these problems, researchers started to use the quasi-experiment design. However, quasi-experimental studies also have limitations. Cornelius (1997) suggested that crying behaviour cannot be measured accurately in experimental conditions or randomised experiments. In a controlled experiment, participants may be forced to cry. Crying is a natural human behaviour that is sometimes voluntary and involuntary. According to Stougie, Vingerhoets and Cornelius (2004), participants cannot be forced to cry because of the experiment condition. Future studies need to carefully use the measurement between self-report or quasi-experiment for the better research result. |

ConclusionCrying is important in our life. The purpose of human crying is shaped by a variety of reasons. Physiologically, tears protect our eyes. Biologically, crying helps us to survive. Psychologically, we cry in order to express our emotions. Socially, crying is helpful for us to communicate and build relationships with others. Crying has benefits and disadvantages depending on the situation. Crying is good when you need better moods. A body can maintain homeostasis by crying. Crying is also helpful for seeking social supports and understanding one's emotional status. On the other hand, crying is not good when you watch sad movies, because it increases the level of arousal. Crying brings you more suffering when you feel hopeless. Finally, crying in public decreases your self-esteem. A major problem with crying research is measurement. Future studies need to be careful about using self-report measurements or the quasi-experiment for better research results. |

See also |

ReferencesBecht, M., & Vingerhoets, A. (2002). Crying and mood change: A cross-cultural study. Cognition & Emotion, 16, 87-101.

Bekker, M., & Vingerhoets, A. (1999). Adam's tears; The relationship between crying, biological sex and gender. Psychology, Evolution & Gender, 1, 11-31. Botelho, S. Y. (1964). Tears and the lacrimal gland. Scientific American, 211, 78-86. Brody, L., & Hall, J. (2000). Gender, emotion, and expression. Handbook of emotions, 2, 338-349. Bronstein, P., Briones, M., Brooks, T., & Cowan, B. (1996). Gender and family factors as predictors of late adolescent emotional expressiveness and adjustment: A longitudinal study. Sex Roles, 34, 739-765. Bylsma, L., Vingerhoets, A., & Rottenberg. (2008). When is crying cathartic? an international study. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 27, 1165-1187. Cialdini, R. B., Schaller, M., Houlihan, D., Arps, K., Fultz, J., & Beaman, A. L. (1987). Empathy-based helping: Is it selflessly or selfishly motivated?. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52, 749. Cornelius, R. R. (1997). Toward a new understanding of weeping and catharsis. The (non) expression of emotions in health and disease, 303-321. Cornelius, R. R., Nussbaum, R., Warner, L., & Moeller, C. (2000). An action full of meaning and of real service”: The social and emotional messages of crying. In 11th conference of the International Society for Research on Emotions. Darwin, C. (1872). The descent of man and selection in relation to sex. : New York, NY: D. Appleton & Co.. Efran, J. S., & Spangler, T. J. (1979). Why grown-ups cry. Motivation and Emotion, 3, 63-72. Faris, M., & McCarroll, E. (2010). Crying babies. Retrieved from https://childcarequarterly.com/pdf/fall10_babies.pdf Freud, S., & Breuer, J. (1974). Studies on Hysteria. 1895. Ed. and trans. James and Alix Strachey. Fruyt, F. (1997). Gender and individual differences in adult crying. Personality and Individual Differences, 22, 937-940. Gross, J. J., Fredrickson, B. L., & Levenson, R. W. (1994). The psychophysiology of crying. Psychophysiology, 31, 460-468. Hasson, O., & Unit, B. (2009). Emotional tears as biological signals. Evolutionary Psychology, 7, 363-370. Hendriks, M. C., Rottenberg, J., & Vingerhoets, A. J. (2007). Can the distress-signal and arousal-reduction views of crying be reconciled? Evidence from the cardiovascular system. Emotion, 7, 458. Hiscock, H., & Jordan, B. (2004). 1. Problem crying in infancy. Medical journal of Australia, 181, 507-507. Kottler, J. A. (1996). The language of tears. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers. Matthews, G., & Deary, I. J. (1998). Personality traits. Cambridge University Press. Labott, S. M., & Martin, R. B. (1988). Weeping: Evidence for a cognitive theory. Motivation and Emotion, 12, 205-216. Miceli, M., & Castelfranchi, C. (2003). Crying: Discussing its basic reasons and uses. New Ideas in Psychology, 21, 247-273. Hendriks, M. C., Croon, M. A., & Vingerhoets, A. J. (2008). Social reactions to adult crying: The help-soliciting function of tears. The Journal of social psychology, 148, 22-42. Plessner, H. (1970). Laughing and crying: a study of the limits of human behavior. Northwestern University Press. Maier, S. F., & Seligman, M. E. (1976). Learned helplessness: Theory and evidence. Journal of experimental psychology: general, 105, 3. Stougie, S., Vingerhoets, A. J. J. M., & Cornelius, R. R. (2004). Crying, catharsis, and health. Emotional Expression and Health: Advances in Theory, Assessment and Clinical Applications, 275. Szabo, P., & Frey, W. H. (1991). Emotional crying: A cross cultural study. In Second European Congress of Psychology, Budapest, Hungary. Truijers, A., & Vingerhoets, A. J. J. M. (1999). Shame, embarrassment, personality and well-being. In 2nd International Conference on the (Non) Expressions of Emotions in Health and Disease. Vingerhoets, A. J., Cornelius, R. R., Van Heck, G. L., & Becht, M. C. (2000). Adult crying: A model and review of the literature. Review of General Psychology, 4, 354. Vingerhoets, A. J. J. M., & Scheirs, J. (2000). Sex differences in crying: Empirical findings and possible explanations. Gender and emotion: Social psychological perspectives, 20, 143-165. Vingerhoets, A. J., Van den Berg, M. P., Kortekaas, R. T. J., Van Heck, G. L., & Croon, M. A. (1993). Weeping: Associations with personality, coping, and subjective health status. Personality and Individual Differences, 14, 185-190. Vingerhoets, A. J. J. M., Sanders, N., & Kuper, W. (1997). Health issues in international tourism: the role of health behavior, stress and adaptation. In M. V. Tilburg & A. J. J. M. Vingerhoets (Eds.), Psychological aspects of geographical moves: Homesickness and acculturation stress (pp. 197–211). Amsterdam: Amsterdam Academic Archive. |

External links |

A poem about giving yourself and others permission to cry (from Jenny Littlejohn of Striding-Ahead.co.uk)

|

Please Do Cry "How often, when someone cries Do you hear them, so meekly, apologise? As if somehow they’ve done something wrong Instead, they’re just singing their healing song How often when public tears do threat your burning, shaming cheeks to wet Do you try to blink away the pain Treat it like some embarrassing stain It seems to me, as we grow to adulthood We are taught, crying in public is just not good And when tears approach we shove them aside Like a part of us, we just can’t abide When you graze your skin and blood appears You know it’s just your body shedding healing tears It’s only natural that blood may flow Allowing healing new skin to grow Just why is it, that when our heart is bleeding, when it’s just love that’s most needing Do those that want to comfort us, sigh There, there now, please don’t cry? So, when next you have a wound to heal Allow yourself to feel exactly what you feel Embrace those tears like a precious prize They are truly a blessing, totally undisguised And when you see the tears of another, turned inwards, their hurt they are trying to smother Don’t turn away and walk on by Ask them instead, please do cry" ~ Jenny Littlejohn  |

.jpg.webp)