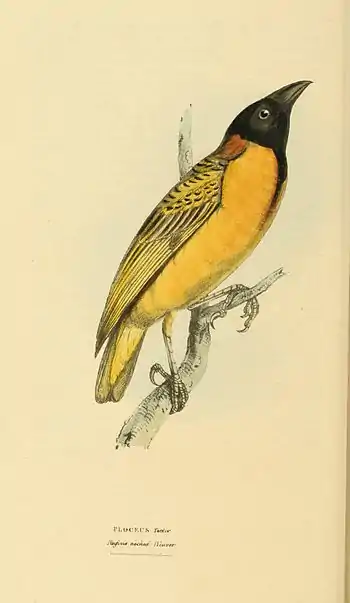

PLOCEUS Textor

Rufous necked Weaver

PLOCEUS textor.

Rufous-necked Weaver.

Family Fringillidæ?

Generic Character.

Bill lengthened-conic, slightly curved, entire, the base advancing high on the forehead, and dividing the frontal feathers, the culmen curved, the commissure sinuated. Nostrils oval, naked: without a membrane. Wings moderate, rounded, the first quill spurious, the five next nearly of equal length. Feet short, strong, the middle toe longer than the tarsus, the hind toe nearly equal with the tarsus. Tail very short, rounded.

Divisions or Sub-Genera.

Malimbus. Vieil. Bill more straight, slender, and lengthened.

Ploceus. Cuv. As above.

Euplectes. Nob. Bill of Ploceus. Toes and claws very slender. The greater quills scarcely longer than the lesser; spurious quill very minute. Type, Loxia Orix. L.

Specific Character.

Orange yellow, varied above with black: head, chin, and front of the throat black: nape with a chestnut band.

Oriolus textor. Auct.

Ploceus textor. Cuvier. Reg. Anim.

Le cap-more. Buff. Son. 19, p. 165. Pl. Enl. 375 (very bad).

The Weaving Birds, confined to the hotter regions of the old world, are chiefly found in Africa, where they represent the Hangnests (Icterinæ) of America: an analogy long since remarked by Buffon. Both these tribes astonish us by the consummate skill with which they fabricate their nests: but the intelligence displayed by the African Weavers is still more wonderful. The curious reader will see a most interesting account of these birds in Paterson's African Travels, or in Wood's Zoography.

Of the present species, although very common in Senegal, nothing appears known beyond the simple fact of its weaving, in confinement, between the wires of its cage. Its total length is about six inches, the minor proportions may be correctly ascertained by the scale on the plate.

If the genus Ploceus of Baron Cuvier be restricted to the old world, it becomes one of the most natural groups in Ornithology. Yet, like all others of an extensive nature, it exhibits several modifications of structure, which the present state of science renders it necessary to define. Whether such definitions are to be termed generic, subgeneric, or sectional, must, in the first instance, depend on mere opinion. It is enough if these lesser groups are defined. To ascertain their relative value is the next step: this is the second, and by far the most difficult process, in the study of real affinities; for not only that particular group which claims our attention, but every other related to it in a higher division, must be patiently analyzed. Hence it frequently results that groups assume a very different apparent station to what they did in the first instance. Are we therefore to refrain from characterizing or naming them, because their relative value cannot, in the first instance, be ascertained? We think not. That genera have been unnecessarily multiplied, no one can doubt, who has looked beyond such circumscribed limits. And if forms of transision, (generally comprising one or two species alone,) are to be so ranked, we must immediately treble or quadruple the present number of ornithological genera. The truth is, that many groups, which in our first process of combination, we are obliged to distinguish, or perhaps name, will, in the second, be united to others. So that it appears highly probable that the number of genera, in ornithology, ultimately retained, will be fewer perhaps than at present. We are, in short, but in the infancy of this knowledge, and our genera, for the most part, must be looked upon as temporary landmarks, to denote the ground gone over, and to be fixed or removed as our views become more extended, by a wider analysis of qualities and relations.

Total length 6½ inches, bill 7⁄10, wings 36⁄10, tarsi 9⁄10, middle claw 1, tail 2½, beyond the wings 1¼.