CHAPTER VII

CALCUTTA IN CHRISTMAS WEEK

NOTHER winter I took heed and reached Calcutta betimes, making sure of hotel accommodations for Christmas week, the gala season of the Anglo-Indian year, when all the fifteen hundred civilians who rule India, and all the officers who can be spared from cantonments, seek the capital.

NOTHER winter I took heed and reached Calcutta betimes, making sure of hotel accommodations for Christmas week, the gala season of the Anglo-Indian year, when all the fifteen hundred civilians who rule India, and all the officers who can be spared from cantonments, seek the capital.

Going from and returning to Singapore there was opportunity to stop in Burma, politically a province of India, but a country quite unique, where the life and the people are so distinct from those of India that one cannot class it with Hindustan any more than Siam. A different religion has made the Burmese a different people, and the absence of caste, the freedom, the equality, in fact, the acknowledged superiority of the attractive, capable, Burmese women have evolved a wholly different social order. There is light, and laughter and gaiety among its people, and the Burman is Malay enough to enjoy a life of leisure. The Chinese come and do the trading, and the Madrasi come to do the work, and the Burmese woman keeps the shop, rules the family, smokes her "whacking white cheroot" with grace, and exerts rare charm.

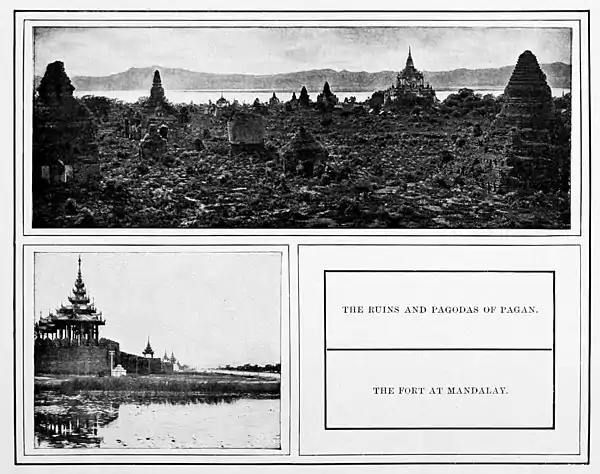

In all sight-seeing nothing is such surprise, so Oriental, so dazzling and fascinating as the great Shoëdagong pagoda at Rangoon. It repays one for all the entomological revels of the "B. I." boats to see that colossal, gilded, and jeweled monument surrounded by picturesque worshipers; to watch "the elephants a-pilin' teak"; to see the colossal Sleeping Buddha at Pegu; and to travel past one hundred miles of sacked rice awaiting the overtaxed railway transportation, as one rumbles by rail to Mandalay, where the fantastic gilt and mirror-covered temples, monasteries, and palaces equal one's dreams of "the gorgeous East." Only seeing can convince one what Buddhism can do for a people in contrast with Hinduism or Mohammedanism, and that the pagoda is always in sight in Burma—the swelling, white bodies tapering to needle spires often gilded and tipped with jewels—the sites of deserted cities like Amarapura and Pagan on the lower Irawadi dotted as thickly with temples and pagodas as ever they could have been with houses. Too many chapters would be required for anything like an adequate exploitation of this picturesque country and attractive people; but until the great European mail-steamers touch at Rangoon the pleasure traveler is warned against the slow coasting steamers on which one lives with the heat and the smells and the motion at the very stern, and where huge brown tropical roaches swarm, past any figures of speech to give idea.

THE RUINS AND PAGODAS OF PAGAN

THE FORT AT MANDALAY

There were brilliant panoramas on Calcutta streets, those glittering noondays and golden afternoons, but the hotels had only increased in numbers, and advanced in price in the few years. Hotels in India are all conducted on the pension or American plan of a fixed rate per day, with everything save wine included, and the charges had risen from the average five and seven rupees to ten and fifteen rupees, to the indignation of Anglo-Indians, who, in no gentle terms, blame increasing tourist travel for the increased cost of living.

I was conducted across a back yard and up a flight of outer steps to a room whose reed matting had not been disturbed in many seasons. "But the Bishop of New York occupied that room last year and made no complaint," said the landlady, dramatically.

"Think how much more Christian fortitude and saving grace a bishop has to have"—and she countermanded the order for a new matting to be laid on top of the old one in shiftless Indian fashion, and decreed a cleaning instead. Two inches of dust, that had to be shoveled off, underlay the matting, then the cement floor was washed with disinfectants, and there was one clean room in one Calcutta hotel that night. When the washstand, grimed with the wear of many seasons, had received a coat of white paint,—without a bowl or article being removed,—it was a splendid apartment—for an Indian hotel. I almost hesitated to exchange it for "one of the best rooms in the house"—a lofty, whitewashed cell with worn cocoa matting on the floor, where twilight reigned all day and no pernicious ray of sunlight fell. "This is Room 66 in the Hotel in Calcutta, one of the best in the house," said an American lecturer once, and at sight of the lantern picture the audience roared with laughter.

"Go and see the Black Hole of Calcutta," said the Viceroy, who had finally determined and marked the exact spot. "I have no need to, Your Excellency. I live there now. Room 18, Hotel," said another winter visitor.

There is little of stock sight-seeing for the tourist—only the Zoölogical and Botanical Gardens and the Temple of Kali; there are no specialties or local opportunities in souvenir shopping in Calcutta, and the European life is not what one comes half-way around the world to see; so that the traveler's stay in this city is usually brief. The fact of its being the capital for so short a season gives Calcutta much of a watering-place atmosphere.

Except for innumerable turbaned and bare-footed servants, the pankha, and the use of many Hinustani words, the life is the life of London—a London with the chill taken off and the sun shining gloriously. Every one waits for the London Times to know the real news of the world; and although the Calcutta newspapers hold diverting advertisements of cinder-picking and ash-sifting rights for sale, and "20 Rhinoceroses Wanted, Rupees 2000 each," local opinion waits on the daily arrival of the Allahahad Pioneer, a nursery of genius wherein Sinnett and Kipling and Marion Crawford first won public applause.

Even in December there is summer heat at noon, and one wears the white gowns of the tropics at that high social hour in Calcutta; for one writes his name in the visitors' book at Government House, all formal calls are made, and letters of introduction are presented between twelve and two o'clock; and on Sundays, after church, every drawing-room hums with visitors' chat. The solid two-o'clock tiffin, following the heavy ten-o'clock breakfast, is so soon succeeded by the four-o'clock tea and the eight-o'clock dinner, that it is a surprise that any one survives the constant feasting which fills Anglo-Indian life. Little can be urged against a climate that permits such Gargantuan feats. The London menu goes with the British drum-beat round the world, and the beef and beer and cheese, the boiled potato, the cauliflower, and orange marmalade are fixed and omnipresent. More continuous than the imperial drum-beat is the sound of the soda-water bottle, on which, with the quinine sulphate, British rule rests. A chill and piercing dampness succeeds sunset, and often at night dense fogs shroud lamp-posts and landmarks until street travel is at a standstill. The modern Calcutta houses have fireplaces where a few lumps of coal diffuse a cheerful dryness, but in the older mansions one is bidden quite seriously to sit nearer the lamp and enjoy its benign radiation.

The Viceroy comes down from Simla in November, and goes on a provincial tour, reaching Calcutta before Christmas, when tents for extra guests decorate the lawns of Government House, of the clubs and great residences; and the empire revolves within the white viceregal palace. The standard flies above the main entrance, red lancers of the body-guard pose statuesque before the portico, and at times a red carpet rolls down the steps and the Viceroy goes in state to return princely visits, or to stand on a pearl and bullion embroidered carpet before his silver arm-chair and lay a corner-stone, unveil a statue, or open some new public building. The great event of the racing week is the Viceroy's Cup, when all sporting India has its eye on the Maidan, remotest cantonments as heavily interested as the cheering crowds on the oval. The Viceroy comes in state, and his loge and lawn are the center of interest and the social heaven of the ambitious, who, between events, parade in the hats and gowns brought out from London and Paris for the races. Rajas and nabobs of degree make a brave show too, with their jeweled turbans, and necklaces worn outside frock coats of flowered satins; the tight-fitting trousers to match as often trimmed with tinsel braid and French passementerie. Thousands of natives, in the universal white garments and turbans of every hue, make such patches of shifting rainbow color in the field, such a living tulip-bed, as fascinates the eye more than any scramble of running horses.

Then all the world drives in the Maidan, making a grand defile down the Red Road and the avenue of statues, along the Strand and the Esplanade by the Eden Gardens, where the band plays at sunset. Eastern and Western fashions are strangely contrasted. The bhisti, with swollen goatskins on their backs, sprinkle the dust, as in the times of Alexander the Great and Cyrus, while automobiles fly by, electric lights prick the blue mists of distance, and night falls with tropic swiftness.

The Viceroy and his wife together hold a drawing-room a few days after Christmas, when a procession of women winds slowly up the white staircase of Government House lined with red-coated red-turbaned servants, and past the many barriers to the throne-room, where the knee is bent to vice-royalty, and one train and bouquet give way to the long procession of trains and bouquets. One does not soon forget the scenes of Lord Curzon's rule in India. The Viceroy, in his white satin small-clothes, girt with his orders and stars and the insignia of the Garter, and Lady Curzon, that supremely beautiful woman of her day, on the daïs beside him in glittering tiara and ropes of pearls, her long train rippling away over the edge of the steps, remind one of certain of David's historical pictures. Lady Curzon has held all native and Anglo-India under the spell of her charm during her stay. There could be no rivalry in beauty, and her unfailing tact and sweet gentleness carry all before her. The Indian people exhausted the imagery of their several hundred languages to describe her beauty, the sun, moon, stars, jewels, and all the goddesses and gopis of their pantheon being drawn into comparison to describe the lovely "Lady Sahib."

A still larger company of men are presented to the Viceroy, receiving alone, at the levee, and then the state balls and state dinners, small dinners and dances rapidly succeed one another, while the Viceroy's private hospitalities are continuous. At the end of each week the viceregal family go to their country house at Barrackpur, fourteen miles up the Hugli, the large house-party reinforced by a company of guests brought up on the yacht to lunch under the great banian-tree. Like Lord Auckland, Lord Curzon, with the Dowager Empress of China, rules half the human race and still finds time to breakfast under that banian-tree. Possessed of that same tireless energy as those two other strenuous rulers of his day, President Roosevelt and the Emperor William, Lord Curzon has given Anglo-India daily shock and sensation since his arrival, and sleepy bureaus and slow officials were galvanized to a life that has known no resting since. There has been no monotony during Lord Curzon's time, and those who have waited for him to weary of hustling the East, to sit back in conventional viceregal fashion and sign the papers brought him, have had to resign themselves to his omnipresence and terrible activity, his thirst for information, and his frenzy for work. He has impressed his vigorous personality upon every branch of the imperial service, and already has visited more native states and distant provinces than any predecessor; ordering, with equal attention to minutiæ, the least details of the increased state and ceremony now attending the viceregal court, the methods of famine relief and plague control, and of the organization of the new district created on the northwest frontier. He has brought India to the world's attention and given it an impetus in the path of progress and prosperity.

The "L. G." or Lieutenant-Governor of Bengal, ruler of sixty millions of people, carries on an elaborate program of hospitalities at Belvidere, his beautiful villa beyond the race-course, and the commander-in-chief and the local military officers at the fort do their part to crowd the January weeks with social events for the keenly pleasure-loving English in exile. It is only at investment ceremonies and at durbars on the arrival of a new viceroy that the native princes assemble at the Calcutta court in great numbers. A few Parsi women in graceful head draperies of pale silks, and loaded with jewels, attend the functions at Government House, and a few elderly and widowed Hindu ladies of rank receive visitors of their own sex; but otherwise the native women of the higher classes remain in as great seclusion as ever, veiled even when they drive in closed carriages. On one afternoon of the week, the India Museum is closed to men visitors, and native women and children come by the gharry-load to the "wonder-house." Foreign women can enter the museum then, mingle with their purdah sisters, and watch the jeweled persons as they stroll about as curious and as ignorant as the smaller children.

The India Museum is rich beyond rivalry in treasures of ancient art. The magnificent carved gateway and rail from the Buddhist tope at Sanchi, original of the casts in London and in Paris, bas-reliefs and images from Gandhara and Amraoti, with treasures and relics from the great temple at Buddha-Gaya, have long made the fame of the museum. When the Piprawah mound at Padaria on the Nepal frontier was excavated, and the stone coffer containing the relics and fragments of the body of Gautama Buddha were found, no archæologist or representative of the government was present, and the "L. G." of the Northwest Provinces, when communicated with, divided the treasures between the India Museum and the King of Siam, the only Buddhist sovereign of this day. The sandstone coffer, a soapstone vase, a crystal vase, some bits of bone and crumbling particles of wood, many pearls, tiny gold beads and flowers, and cut amethyst, topaz, carnelian, coral, garnet, beryl, and jade stars, together with larger beaten gold ornaments in the shape of the swastika, came to this museum—more authentic relics of the founder of a great religion than any European cathedral contains. It possesses also the inscription recording the deposit of these relics of the body of the Buddha in that mound by the members of the Sakya clan—a treasure of archæology which makes real the personality of the Buddha, the founder of that religion no longer a solar myth. This museum has an average of sixty thousand visitors a month, equaling nearly the throngs at the Louvi'e; but the company of bare-footed, sheeted Bengalis are so aimless and vacant-looking that one questions whether the carefully planned exhibits reach beyond the retina, whether they have any comprehension of the objects.

One does not expect to find a great leisure class in India, where the struggle for existence is so close and bitter, but watching the idle drift of natives past this stretch of Chowringee Road, and the Maidan before the museum, even more than through the labyrinthine bazaars, one is appalled and oppressed with the realization of India's population—294,360,356. All day the lean, wistful, apathetic men stream up and down, up and down, going nowhere, doing nothing—hundreds passing at any moment, thousands in an hour, with no women and rarely a child in sight. Each Hindu, in his dirty head-sheet, represents a family crowded back somewhere in the city slums or in mud villages beyond. One easily believes the census figures, and sees how the frightful problem of over-population besets the empire; how necessary, almost, are plague and famine, in lieu of wars, to reduce the swarms and herds of these lank, inert, torpid, half-fed, half-clothed, half-alive Bengalis, When the sixty million Bengalis are crowded seven hundred and even nine hundred to the square mile of this fertile province, and are the most prolific of Indian races, they must reap three harvests a year even to half live, as they do. Long-continued peace and the sanitary blessings of English rule have so preserved and increased human life that disease and starvation seem too slow agents to accomplish the necessary reduction. Only tidal waves and earthquakes, annual disasters like those of Pompeii and Martinique, could keep the population within bounds.

The Hindus are not a laughing, light-hearted, joyous people, and the Bengali is the most melancholy of them. He has little, almost no sense of humor, his voice is always in a sad minor key when not quarreling, and the corners of his mouth are permanently drawn down. A sad sobriety is his sense of dignity and good form. The hotel porter calls a "fitton" (phaëton), not with the tyrant voice of command, but with the sad, piercing wail of a banshee. The sais, wrapped in melancholy and a quilted bed-spread, responds with a mournful loon cry, and urges his lean, despondent horses forward, the running sais in tattered sheet hanging on behind, like an old dust-cloth, with bags of green fodder. He jeers but never laughs, and one wonders if he can, with so little room for a normal pair of lungs in that thin, flat body and narrow chest. With no oxygen to speak of for generations, they can hardly be cheerful or energetic. Athletic sports are not in the line of the young Bengalis of the Brahman castes who crowd the schools, take all the prizes, and fill the government offices,—Young Bengal being usually a superficially educated poll-parrot quite as offensive and hopeless as Young China. The Bengalis are slow to reward the Christian missionaries who have worked among them for a century, but they are converted to Mohammedanism in droves, Whole villages adopting that casteless creed.

The laboring Hindu seems generally incompetent, and sadly lacks inventiveness, originality, ingenuity, and the all-embracing but indescribable faculty known as "gumption." His appliances, tools, and instruments are unchanged since the day of Alexander, and the mechanical sense seems wholly denied him. Everything has come to him with his conquerors. With spindle legs, flat chest, and shrunken arms, one wonders how one of them can do the heavy work of dock-yards, harbors, railway yards, and iron foundries. Everything is hoisted on the head and shoulder, and so little is carried in the hand that handles are superfluous ornaments on luggage. One meets grand pianos and packing-cases of equal size carried on the heads of eight and twelve men, who step together with locked arms. I watched one coolie's seven attempts to carry ten pasteboard boxes from one shop counter to another. Each time he heaped the load on one arm his draped head-sheet fell away. Each time he reflung the sheet the boxes dropped from the limp arm, and the alternating play went on, until one would have expected an employer to deal blows—or for any rational creature to throw away the sheet and get to work. Centuries have not evolved a way of tying or pinning the woman's veil fast, and weary housekeepers describe the ayah's efforts to make a bed and keep her veil in place as an alternating affair like that of my coolie and the ten boxes.

The curse of caste and all the difficulties its observance implies further complicate dealings with these people, and a century of enlightened rule has not freed them from its tyranny. The railway has done something toward leveling castes, but for the journey only. Instead of reviling and recoiling from the railway as an invention of the defiling European for the express purpose of destroying caste, the Brahman artfully calls steam one of the thousand and eight uncatalogued manifestations of Vishnu. He conceals his sacred thread, washes off his caste-mark, and rides in the jam of a third-class car, touching sweepers and water-carriers and corpse-burners, and trusts to after-purification. Instead of the Chinese hostility to railways, they have so much adopted them for their own that there is already a hereditary railway caste, and railway workers of the third generation are following their fathers' occupation as naturally as if it were an occupation of centuries' inheritance. One never arrives at an end of the puzzling caste distinctions. With the four great castes of Brahmans subdivided into eighteen hundred and eighty-six castes, it is beyond any European mind to master its intricacies. Because of caste, no one jostles you in the street, and insistent touts keep a safe distance.