CHAPTER III

WITH CHIDAMBRAM'S BRAHMANS

T was our fine old Tamil Turveydrop, Samuel Daniel, who induced us to visit Chidambram after we had abandoned it in favor of Conjeveram, where the temple was said to be richer, the jewels more splendid. This artful one pictured "the cleverosity and numerosity of the sculptures," also "the numberlesses of the goddesses and the beauteousness of the temple's dancers, which makes it so popular for visitors," and our interest revived.

T was our fine old Tamil Turveydrop, Samuel Daniel, who induced us to visit Chidambram after we had abandoned it in favor of Conjeveram, where the temple was said to be richer, the jewels more splendid. This artful one pictured "the cleverosity and numerosity of the sculptures," also "the numberlesses of the goddesses and the beauteousness of the temple's dancers, which makes it so popular for visitors," and our interest revived.

As necessary precedent to every move one makes in India, enough telegrams were sent to negotiate a treaty. We wired the Chidambram station-master to have conveyances ready the next midnight to take us the three miles to the dak bangla. We wired the bangla-keeper that we were coming, two beds strong. We informed the local magistrate and the high priest that we wished to make an offering to the temple and to celebrate in honor of the goddess with a great dance in the Hall of a Thousand Columns and to see the famous temple jewels. Last, we besought the section superintendent of the railway to reserve a compartment in the next midnight train that would bear us away from Chidambram.

With the remoteness and seeming isolation among the black faces one has no fear or concern in these Hindu communities, trusting implicitly to that safety and order guaranteed one wherever the British flag floats and Kaiser-i-Hind's initial letters grace official property. Else, when we stepped out on the lonely platform at Chidambram that rainy midnight, we would have thought twice before picking our way through sleeping pilgrims in the open waiting-room, and stowing ourselves away with every joint bent in a tiny box of a native cart, or "lie-down-bandy," for the ride into unknown blackness beyond. Daniel compressed himself with David and the larger luggage bundles into another small box on wheels, and the ponies spattered down a muddy road in the black shadows of overarching trees. Our driver had no turban, his hair was long and snaky, and the jerky motion of the bandy, and the driver's frequent flights out over the shafts to lead the pony by the bridle over bridges and around corners, sent those locks rippling down his back—and my back, too, as I sat hatless, crouched flat on the bandy floor behind him. After what seemed a long race through the reek and blackness, past sodden fields and through dreary mud hamlets, we came in under the shadows of the great trees surrounding the dak bangla.

With the abrupt reining up we slid out, or fell out, of the bandbox of a bandy, and our cramped members slowly jointed out straight again. Knocks, thumps, and calls brought no response from two front doors, and there was an uncanny quarter-hour of waiting before the swaying lantern of Daniel and David's bandy turned in at the gates—and yet another eerie quarter of an hour while the bandy drivers muttered in the near darkness, and our two protectors pounded and shouted at a far-away door. The moon struggled out in rare glimpses and gave us suggestion now and then of a great lawn and trees, a long, low, white building whose eaves extended over a continuous flagged porch—the regulation rest-house built by government for the use of traveling officials and other Europeans.

A babel of angry voices came from the back of the compound, the loud talk and back talk, the incessant wrangle and jangle of untuned bells and Hindu servants, the most quarrelsome lower class in the world, after the Chinese. Their bickerings are an annoyance that frets the spirit and wears the nerves of the most adamantine traveler, and it is no wonder that the Buddha, and all saints and reformers, first fled to the jungle for years of silent meditation. The keeper of the bangla appeared with his keys and a lantern. "Oh, yes, certingly, memsahib," he had received the telegram in due time and had tightly locked up the bangla and his own quarters and gone soundly to sleep—Hindu irresponsibility, ungraciousness, and indifference to the usual degree.

The door clanged open and showed us the regulation lofty, cheerless, cement-floored room, as fit for prison as superior occupancy. One remembered those creepy "other stories" of Rudyard Kipling where lunatics and delirium tremens subjects habited, and suicides took themselves off in, just such cheerless rooms, and that other more grisly story of the dead man concealed on rafters overhead in just such a forlorn place. The candles burning sullenly in tall glass bells showed us a great dining-table, ponderous arm-chairs and lounging-chair, and a broad cane-seated settee for a bed. Another such hygienic couch of the country was brought in from a black, echoing room beyond, and the servants spread out our red razais, or wadded calico quilts, which every traveler in India must carry with him as bedding and covering, just as the Klondike miner carries his blankets when he "hits the trail." The rubber pillows were inflated, and the apartment was completely furnished and in order for occupancy. Before the alcohol lamp had boiled the water for the beef-tea of our midnight feast, the servants were snoring on the flags of the portico, lying on the door-mats with only a thin bit of dhurrie covering them, despite all one hears of the deadly effect of night air and the chill before the dawn. The most awful stillness succeeded, a silence that made one's ears ring, hushed our voices, and made us unconsciously put down spoons and cups noiselessly. No one had raised my terrors then with tales of the still occasionally existent thugs of southern India, of thieves who throttle by night and stealthily kill or maim an unbeliever as an act acceptable to Kali and the other destroying divinities. The situation was all novel and amusing, and the poverty-stricken interior, the forlorn banquet-hall of this Waldorf of the neighborhood, furnished all the real color one could want. The stealthy dripping of the trees told of another gentle shower, and the steady snoring on the porch was as comforting and hypnotic as the purring of a home cat by the hearth—sufficient assurance that all was well at one o'clock and that the British government in India still lived and protected us.

At seven o'clock repeated calls brought no answer from the portico; the silence of broad daylight was more complete than that of midnight. The flagstones were deserted, and not a sign of life appeared on either side of the bangla. David and Daniel had most literally taken up their beds and walked—far away beyond hearing. A little girl with a nose-ring crept out and looked at us, another one joined her, and the two stared and smiled, nodded their nose-rings with friendly flops, and looked their fill—a steady, continuous, fascinated scrutiny—for a whole half-hour before David and Daniel appeared bearing tea and toast. Then David's irate voice rose in volume, well-sweeps creaked and tubs were filled, chickens ran cackling, smoke rose and sounds of life and cheer came from the keeper's house and kitchen. David wrathfully told how he had had to go to the village bazaar, a mile away, to get even the firewood to cook the first breakfast.

While David ruled in the primitive mud kitchen the keeper of the bangla laid the table on the front portico, overlooking the broad, glistening green lawn, where squirrels frisked and little green parrots squawked and flew about. The china, glass, and cutlery provided at these dak banglas are always good, and there is usually some attempt at splendor in electroplated toast-racks and marmalade-stands. Our esthetic keeper of Chidambram put a great bouquet of yellow crysanthemums on the table, but the tablecloth was a thick honeycomb stuff, either a bed-spread or a bath-towel that some guest had left behind; and it was frescoed with hospitable records of a useful past in egg, coffee, and claret stains on a ground toned by the roadside's red dust of a season.

The local magistrate appeared for a morning call, entering the gates in a large bullock-bandy, or covered cart, drawn by two magnificent white bullocks with humps on their shoulders, the bells on their necks announcing the pace of their leisurely trot. The turbaned and white-draperied grandee had hardly descended from this seeming vehicle of state or chariot of religious ceremony when the driver loosened the yoke, tilted the bandy over, and turned the splendid creatures loose to graze on the lawn. This custom of southern India, of releasing bullocks and ponies of their harness at once, gives hotel and bangla grounds in the Madras Presidency always a homely look, suggestive alike of pasture, race-course, and stable-yard.

The magistrate was one of the finer types of high-caste Hindu, who added to his own Brahmanic culture and inherited refinement an English university education and acquaintance with other ways of living and thinking. He had all the Oriental suavity and graceful address, and talked with us two of the despised sex quite on a social equality. He sat long at his ease, commenting upon the customs of his people and the peculiarities of life and architecture in southern India. He deplored the low estate and want of education among women; praised the new era and the blessings of British rule, the good roads, schools, hospitals, and things not dreamed of before, that had come with the Western education, which had only begun to reach the mass of the people. His Western education had not, however, steeled him to shaking hands with a casteless unbeliever, and he kept tables and chairs between us as he rose to go.

"I must go and hurry up the priests," said the suave judicial. "Since they know you cannot leave until midnight, they will not try to be ready before late afternoon. At one o'clock I will send my bandy and peon for you. You will find my bullocks faster than those you would get from the bazaar." And with more beautiful speeches about the honor of our visit to Chidambram and our appreciation of Dravidian art, he backed and bowed himself away to his bandy, with furtive glances lest we yet lay defiling hand on him, and send him through all the details of his morning toilet again, as the least of ills.

It was past one o'clock when the stately bullocks again tinkled down the road to the bangla; a peon with a broad sash and metal plate on his breast forming an escort of honor. There was no telling how much our occupancy defiled the magistrate's bandy while we progressed magnificently along a shaded road, between garnered fields and the lines of mud houses constituting villages—mud houses with mud floors, and mud porticos or shelves where the occupants loll by day and sleep at night. Men and women gave friendly looks, the women draped gracefully in the single long sari, or winding-cloth, that, either red or white, is a foil to the dark skin and lends majesty and picturesqueness to the frowziest. Nearly every woman wore silver bracelets and anklets, armlets, finger-rings, ear-rings, nose-rings, and necklaces past counting, and one never knows what silver jewelry can effect, nor its artistic value, until he sees it against these sooty Tamil skins.

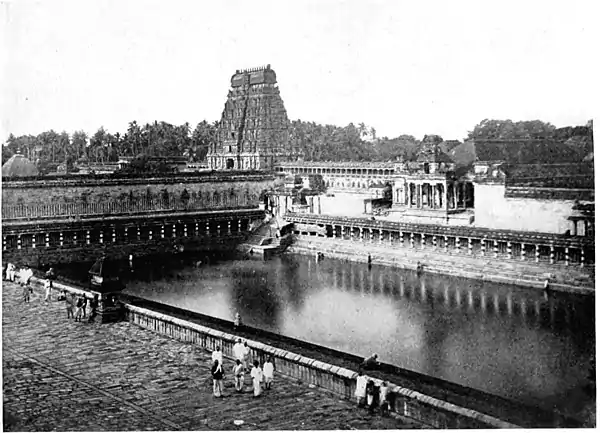

The village of Chidambram clusters low before the soaring gopura of this oldest Shivaite temple of the south, and its seventy rest-houses shelter thousands of pilgrims at every December mela. Four of these great pagoda-like structures, each 160 feet in height, carved, painted, and gilded over, with a massive trisul, or trident ornament of Shiva, for capstone, admit to the quadrangular space of thirty-two acres occupied by the labyrinth of shrines and courts and halls around the great tank. The temple was built a thousand years ago by a pious raja, who had seen Shiva and Parvati dancing on the near-by sea-shore; and the holy of holies is a golden shrine dedicated to the god of dancing. Another tradition says that a Kashmir prince of the fifth century brought three thousand Brahmans with him from the north and founded the temple. The greatest popularity was given the temple when "the golden-colored emperor," a leper prince who had come south on a pilgrimage, was cured by bathing in the temple tank, and thousands emulate him every year.

Repairs were being executed in many places, at the instance of a pious Hindu of Madras, and we picked our way through damp and dripping courts littered with freshly carved stones, crawled under scaffoldings and inclined planks, until we were well confused with the multiplicity of shrines, the garlanded and greased images of Shiva, Parvati, Ganesha, and the Bull, and always the figure of the dancing god with one knee acutely bent and the other foot flung with abandon. The courts were empty, the shrines deserted, no worshipers, no workmen, no priests, no crowd of idlers, as in the busy Madura and Srirangam temples. No signs of preparation for our visit were evident, and we sent the peon and Daniel and lay brethren in hot haste to give the alarm, lest the function be delayed past sunset. A few languid villagers stole in and stared, the longitudinal sect-mark of Vishnu on the forehead and the loosely drawn dhotee drapery around their shoulders giving them a strong resemblance to our red Indians of the prairies in war-paint and reservation blankets. Then more waiting succeeded, more messengers were despatched with more vehement advices, and Daniel, with the air of great cares pressing on him, paced the arcades meditating, speaking now and then with magnificent gestures, like a real raja. "My birthly is Christian," he had informed us in the first sanctuary of heathendom, that we might feel free to comment and question at will.

A band of Brahmans in fresh war-paint finally arrived, and their fierce hawk-like gaze, their eager, excited, hurried air, might have given one qualms of alarm at our isolation in this labyrinthine fortress of a temple, remote from any European settlement,

GOPURA AND TANK, CHIDAMBARAM TEMPLE.

They looked at us, their prey, with eager interest, and with shouts appropriate to those about to offer living sacrifice to the gods; with whoops and hurrahs this band of Brahmans conducted us to the main shrine and struck the gong to announce our presence to the god—an ugly, greasy, black little image, hidden somewhere out of sight in an innermost sanctuary. We saw only an open-fronted chapel, whose floor was three or four feet above the level of the court-yard; and as we advanced to it the priests brought gold plates heaped with garlands of strung flowers, which they flung around our necks. The gold plate was extended for our offerings, and at sight of the rupees of propitiation the Brahmans pushed, pointed, gesticulated, and shouted to one another. Only the Arabs of the Nile, or the boat-women of Canton, could raise such din and hullabaloo, produce such waves and volumes of harsh, ear-splitting sounds. It seemed as if they were about to tear us to pieces and were quarreling about the lead, but it was only intense interest, pleased excitement, and glee at the prospect of another gala day for Chidambram, with a fine lot of rupees to be divided afterward among the charter members of the close corporation. They shouted, screamed, pushed, and all but defiled themselves by touching us, in order to point out things to us and attract attention. A half-dozen tried to be leaders of the expedition, to establish a special protectorate over us, each leading a separate way, the magistrate's peon making appealing dumb show for us to follow him in another direction, while Daniel, disentangling himself from the Brahman mob, made deprecatory gestures to them, bowed low to us, swept his hand obsequiously to guide us in a still different quarter, and said in mild, honeyed tones: "This way, your ladyships, this way." His suavity won, and all garlanded, as if ready for slaughter, and preceded by the band of temple musicians, we were led on and on, from shrine to shrine, the hawk-eyed Brahmans shouting wild acclaims, just as in a triumphant progress on the stage. It was all well-mounted grand opera, a deafening Wagnerian representation; and when we stood with the great chorus grouped before one gilded shrine with a golden roof and a golden flag-staff—a mainmast plated with hammered gold— it was a fine scene for the curtain to have fallen on. They led us to a store-room full of silver palanquins, chariots and platforms, silver bulls, elephants, goats, and peacocks, and explained how these and the sacred images are drawn in procession through Chidambram streets and courts on the great days of the heathen year. There the temple musicians fought and won chance for fullest action; and drum, trumpets, and castanets raised such echoing din in the holy inclosure that we were literally distracted when, having "visited the architectures, "we were conducted to the treasury and given chairs around a long, low table covered with a greasy red-silk cover. Deafened by the thump and blast of instruments and the vent of sacerdotal lungs, and overpowered by the weight and suffocating odors of the garlands of jasmine, tuberoses, marigolds, and chrysanthemums around our necks, we let those twenty-pound weights of vegetable adornments slip on to the backs of the chairs, and had Daniel hint to the Brahmans that our presents to the temple would be greater if the noise were less. He explained delicately that we were from another country than that of the usual visitors to Chidambram; that people in America were accustomed to speak in soft, low voices, and to keep very silent in their temples. What a Talleyrand was spoiled when that soul in its present incarnation habited the body of Trichinopoli's great guide! Daniel spoke, and the hush of midnight succeeded for about ten seconds. Then the Brahmans whispered; their buzz rose to audible speech, and our ear-drums were again violently beaten until the mercenary company was hushed by significant gestures from Daniel. The musicians fingered their instruments sadly, but Daniel was supreme, and when one strapping head Brahman fully caught the cue, he outdid Daniel in silencing the sacerdotal screamers for the rest of the afternoon.

When the magistrate came, followed by temple peons bearing great boxes tied up in red silk, he brought with him his six-year-old daughter, Thungama, the "little golden lady," as her pet name was translated, a disdainful, arrogant mite, who snubbed us soundly, but gave such cool, supercilious glances of high-caste scorn from such deep, dark, liquid, mysterious eyes that we forgave her. She wore a little cotton skirt and jacket, and silver anklets; and her hair, divided at the brow in two plaits that framed the face, held a semicircular rayed ornament of pearls. This star-eyed beauty did not want to be looked at nor addressed by us, and had a dread of being touched by pale strangers with uncovered faces and no caste-marks, stamps, or guarantees of position on their brows. This imperious mite ruled her father royally, received the respectful homage of the sleek old Brahmans, and was petted and passed from papa to priest and peon as suited her whims. There was the finest ethnological exhibit around that treasury table,—the magistrate, his daughter, and ourselves in front, and the Brahmans ranged in triple circle of fine, spirited faces above splendid shoulders, a prosperous-looking, sleek, and well-groomed board of temple aldermen, directors of that close corporation of Chidambram, living for so many generations on the fat of the land and the offerings of pilgrims, and inheriting the intellectual monopoly of ages. Each one had been invested in his youth with the sacred Avhite cord, had served his time of probation, had married and raised a family, and now was enjoying his magnificent prime before disappearing from Chidambram and following the strict Brahman routine of the end of life. It seemed amazing that there should be a community where the physical average was so high; and commenting on the many fine, noble, and dignified countenances and the statuesque shoulders, Daniel explained it all: "Yes, the Brahmans are always splendid of appearance like these. It is the hereditary heirness of their high descent."