CHAPTER XXV

JEYPORE

T Agra we were midway in the peninsula—eight hundred and forty-one miles from Calcutta, and eight hundred and forty-eight miles from Bombay. It was very cold, and rain was falling in sheets when we started, late at night, to ride the one hundred and forty-nine miles to Jeypore, and during the night it grew colder. Clouds of dust came through the loose, rattling carriage-windows, and when we shook off our razais at daylight, near Jeypore, there was a small dust-storm in our compartment.

T Agra we were midway in the peninsula—eight hundred and forty-one miles from Calcutta, and eight hundred and forty-eight miles from Bombay. It was very cold, and rain was falling in sheets when we started, late at night, to ride the one hundred and forty-nine miles to Jeypore, and during the night it grew colder. Clouds of dust came through the loose, rattling carriage-windows, and when we shook off our razais at daylight, near Jeypore, there was a small dust-storm in our compartment.

The pompous, fat proprietor of the Hotel Kaiser-i-Hind was strutting the platform in a solferino plush coat, waving a telegram and shouting for "Eliza! Eliza!"—meaning the person who had sent the message. His rival, the proprietor of the dak bangla, fawned at our elbow, beseeching us to come to his house instead, and there was wordy war between the two across me, charge and counter-charge. "I will furnish elephant for Amber, no charge!" shouted one. "Oh, memsahib! memsahib!" hissed the other, "that elephant no good elephant, not got teeth." "Mine is first-class family hotel," roared the solferino villain. "Oh, his is dirty, rotten hotel," wailed the other. "Please come my house, please come my house, I am poor man," bawled the bangla-keeper, as the big solferino banged the carriage-door on his trophies and climbed the box to guard us from being kidnapped on the way.

The dining-room of the Kaiser-i-Hind was in the cellar-like ground floor, and an outside staircase led to the cement terrace or roof on which the bedrooms opened—lofty rooms, with many doors and long windows to admit air in the hot weather when the hotel is empty, and fireplaces the size of a crumb-tray to warm them on the frosty nights when the place is filled with shivering, sneezing tourists. Two dozen times the solferino one asked me if I wanted a guide for Jeypore, and as many times he received the decisive "No." Two babus were breakfasting in the general room, quite like Europeans, and speedily opened conversation. No discouragements could check their volubility, and we watched to see what game was premeditated. "I am not common man," said the larger turban. "I am prince. I am Nawab of Behar. Go! fetch me those letters from the duke," he said to his companion, who returned with a greasy note, worn like a beggar's certificate. The secretary of the Duke of Connaught had written to "His Highness Mer Abdul-asal Alum Khan, Nawab of Behar," to express condolences on the death of the Nawab's wife. Then this doubtful Nawab, eating in the public room of an inn with casteless unbelievers, told us that his family owned the Esplanade Hotel in Bombay, and that he spent much time there. He offered to telegraph to his brother-ruler of Indore, or to any native state we might wish to visit. He would even take us around Jeypore and show us the sights, since he had nothing else to do that day. He would take us to the shops—and then all suspicions crystallized without this democratic raja adding: "I will take you to the best shops. I am not common man after commission." This latest form of tout, the princely one of the table d'hôte, was such an amusing climax to our touting experiences that we could hardly keep serious countenances before the clumsy confidence-man and his accomplice. His tongue ran on and on, in sheer joy in its running. "I want not commissions on what you buy. I want not money in this world—only friends, and weeping when I am dead." We could not tell how much conspiracy there was between this pair and the solferino landlord, who had been so persistent about our taking a guide; but the solferino one handed the Nawab into a carriage with a great flourish just as our "fitton" drew up. "You are going to the museum?" asked the Nawab. "So are we"; and he was whirled away without escort or outriders. He stood on the museum steps dumbly staring when our carriage went past him toward the city gates, and when we did return to the museum, two hours later, the Nawab was waiting and showed the strain of that long suspense. The pair followed us from case to case for a while, profuse in praises of what we looked at longest, voluble until we put direct questions to them about the methods and processes of manufacture of some of the old art objects. "I can find you shop to make you copy of anything you see here," repeated the bogus Nawab several times plaintively. To end the farce, which had then been played long enough, we confided loudly to each other in prearranged dialogue that we had not an anna left for shopping in Jeypore—only our railway tickets and rupees enough to get to Bombay. The Nawab melted away without adieu and was seen no more.

This art museum, housed in a beautiful palace in a park, is filled with the choicest examples of old pottery, brass, enamel, gold- and silver-work, carving, weaving, embroidery, jewelry, and everything else on which Indian fancy and genius lavished decoration in the past. At the art school in the city replicas of many of the museum objects were for sale, and others could be commanded. The class of young brass-beaters sat in the cellar-like entrance of the school, beating out Saracenic traceries as borders of large brass trays sunk in beds of pitch; and a dyer and his wife next door walked up and down, stretching between them to dry the rainbow-striped cotton head-sheets which are a specialty of Jeypore. Everywhere in this "rose-red city, half as old as time," the street groups were so theatrically picturesque that we forgot everything in watching them. The city is new, architecturally, and its two long, straight streets, crossing at right angles by the palace walls, cause all picturesqueness to converge there. The crowds were so brilliant and fantastic that one remembers Jeypore as some pageant in grand opera, the bazaars more spectacular than even those of Lahore. At noon, we saw the broad main street crowded from curb to curb with men in white clothes, with gay turbans and shawls,—a crowd that swayed and surged and moved until the long expanse of turbans was like a tulip-bed in the wind. It was the climax of all Indian street scenes, and such a kaleidoscopic play of color as could only be seen there on the day telegraphic bulletins are received from the government opium auctions, which fix the price of the drug for the month.

At the great Four Corners there is a monumental fountain, and there elephants continually pace by, camel-trains pass and repass, and pigeons descend in clouds if one tosses a few grains in air. Sheeted women, with jingling anklets and full-swinging skirts, come to the corner of the jewelers' bazaar to buy their glass, brass, lacquer, and more precious bangles and nose-rings. There were wedding processions passing the fountain all that sunny day, which had been declared the lucky one of the month. Many cortèges were preceded by elephants in rich velvet and bullion trappings, their faces, trunks, and ears elaborately painted. Jeweled bridegrooms went by in velvet-lined palkis hung from silver yokes, and from time to time the processions halted, a canvas was spread on the ground for the company to sit on, and nautch-girls—middle-aged colored women in bunchy accordion skirts and full panoply of jewels—gave a deliberate song-and-dance interlude. These mature sirens literally "trod" their slow-footed measures in clumsy, dusty leather shoes that a hod-carrier might wear. Each family circle

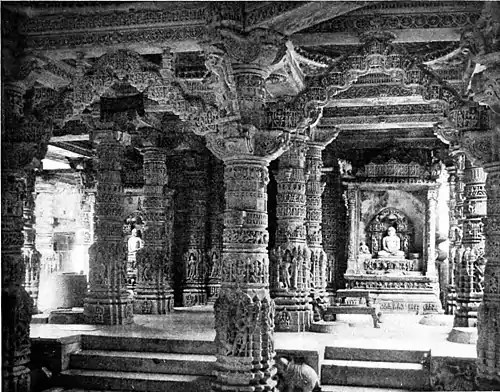

INTERIOR OF JAIN TEMPLE, MOUNT ABU

There were the regular, cut-and-dried tourists' shops filled with crudely made weapons, rough brasses and potteries, for which gullible folk pay twice the London price; and one such proprietor met us at the door with his visitors' book and insisted that we should read the praises of himself, his wares, and the Indian tiffin he serves good patrons, written but the day before by some young travelers from New York. He dilated upon the virtues of Americans, and showed us the boxes and boxes of trumpery stuff bought by those tourists; and it was great comfort to us, the worthy poor, that we were not as the millionaires are—to be taken in by Brummagem goods and cast-iron sword-blades at double the Broadway prices.

At another shop of archaic weapons that had but yesterday come from the foundry, we bought an elephant-goad for peace and sociability's sake, and sat for an hour to watch the panorama of the main street. The bearded proprietor bubbled away at his hooka and pointed out the Jeypore celebrities as they went by—the prime minister, the chief magistrate, the political resident,—even the treasurer going in state, with an artillery escort, to pay visits. A group of Brahmans bringing sacred Ganges water from Benares had military escort, too, and a military band; and there was an air of religious state to all the great ekkas drawn by noble white bullocks, the kincob curtains but half concealing the rainbow-wrapped women within. Noble graybeards pranced by on Arab horses, and five wedding processions, with jeweled nautch-girls in gold-gauze dresses, passed before us, the wise old elephants looking very bored with all this fuss and folderol over the marriage of small boys. A customer came and bought some big brasses; a minion ran off and found a dilapidated box for a few annas, and they patched and mended it on the spot. Then the proprietor swept a glance over the crowded thoroughfare and let forth wails like a muezzin on a minaret. A woman, bent under a great bundle of forage, stepped aside, dropped her small haystack on the shelf-like floor of the shop, and the packer's material was bought from her, a simple, direct, and primitive proceeding that delighted me.

Such scorching sunshine and piercing winds were never experienced together as in Jeypore. One needed an umbrella as protection from the sun and fur wraps as protection from the wind at the same time. We tiffined in the icy dining-room and took coffee on the scorching terrace, where merchants of arms gathered daily to display their ancient weapons—cast-iron stuff made to order in England to furnish the "cozy corners" of Christendom, to hang on the walls, and to prop up the divan draperies of so-called Oriental rooms.

It was on one of the most brilliantly sunny and piercingly cold days that we drove across the city and out to the flat country beyond, where abandoned gardens, crumbling tombs, lone minarets, and domes lined the road, and alligators basked by neglected tanks where green scum floated. As we drove into a courtyard, a weary old elephant with a painted face sadly in need of retouching saluted us with foot and trunk. It knelt, and we climbed to a rickety charpoy, or string-bed frame, covered with doubtful razais. After the noble beast at Gwalior, with its splendid trappings and comfortable jaunting-car, this ill-pacing, moth-eaten, tourist elephant of the Raja of Jeypore was a disappointment; and after it had lurched and lumbered along a few miles that we might have done more comfortably in the carriage, our disgust was unbounded. We were disenchanted before the creature began the steep ascent to the deserted palace of Amber, delighted that the elephant is fast being relegated to the background, a creature for shows and ceremonials only, the railway and the automobile displacing it as a means of travel, and American overhead machinery crowding it out of timber-yards; and the Delhi durbar of 1903 very probably the last great parade of state elephants.

All the way out from the city the road had been streaming with people in brilliant clothes and the kaleidoscopic street crowds of Jeypore continued far into the country. Troops of Rajputs in green, white, and yellow clothes, on foot, in bullock-carts, sitting by the roadside, and going in and out of temples, enlivened the way, and, as we mounted the side of the mesa, we could see this brilliant ribbon of road stretching away through the level of the abandoned city of Amber. The lurching elephant gave us momently finer and wider views out over the plain of ruins, and finally lumbered into a court of the fortress palace and knelt for us thankfully to dismount. In the little temple to Kali, at the palace entrance, the floor was still red with the blood of the goat just sacrificed, and we had heathendom fresh and hot there at the maharaja's door. Guide-books and sentimental tourists have said so much in praise of Amber that we had keyed our expectations too high. Also, one must land at Bombay and see Amber before seeing Agra, Fatehpur Sikri, Delhi, and the rest to value it so highly. The tinsel looking-glasses and plaster rooms at Amber were wearisome. We had seen too many before. The pavilions, the baths, and the gardens seemed small and contracted, and even the pomegranate-trees grew in pots. Best of all in the palace was the high balcony, where we enjoyed a picnic tiffin and a view out over the lake and the plain of ruins and tombs. The elephant took us slowly down hill with the greatest possible discomfort, the mahout goading it until drops of blood stood on its neck, and we rejoiced that there was no more elephant-riding in prospect that season.

We were delighted to get back to the fantastic, pink-plaster streets of Jeypore and join in its theatrical pageantry, throw wheat to the pigeons in air, join arrested wedding processions, and watch the sedate old dancers in brogans tramp their slow measures and sing their nasal songs. The street juggler looped the torpid python around his body and held the head before him to be photographed, as if the coiling creature were only a garden-hose with fangs in the nozle. The streets fairly blazed with color in the last red and yellow rays of sunset; brilliant turbans and head-sheets were moving languidly in every direction around the four-corners' fountain; pigeons whirled in clouds and trotted beside us by hundreds; flocks of noisy crows flew to settle for the night in trees just outside the city wall; and when we reluctantly drove away the frost-haze was silvered by moonlight, and Jeypore remains a brilliant picture—too spectacular and color-satisfying to be real, too good to be true, a certain feeling possessing one that the scenery was rolled up that night and the troupe went home or on to the next town. In the cold hotel we slowly congealed, enthusiasm declined, and we joyfully quoted Lord Curzon's opinion: "The rose-red city over which Sir Edwin Arnold has poured the copious cataract of a truly Telegraphese vocabulary, struck me when I was in India as a pretentious plaster fraud." In memory one reverts to Sir Edwin Arnold's view, sees only the fantastic pink palace fronts, the brilliant turbans, the wedding processions, and the jeweled women switching their red and yellow skirts in the sunshine; and of all places in India, I should like best to be put down for an hour in the streets of Jeypore, when the midwinter sun is shining, the opium-market is lively, and the astrologers have declared it a propitious day for weddings.