CHAPTER XVII

OLD DELHI

NE gets the full sense of antiquity in driving south from Delhi for eleven miles over a plain strewn with the ruins of seven earlier cities that preceded this modern Delhi, or Shah Jahanabad. Dwellings have crumbled away, but forts and tombs have withstood the ages, and there is a very feast of graveyards all the way to the Kutab minar. Hoariest of all the memorials is the carved stone column of Asoka (240 b.c.), inscribed with the Buddha's precepts against the taking of life, and which stands in Tughlak's ruined fort at Firozabad. At ruined Indrapat are the remains of the lovely inlaid mosque and the tall tower from which the emperor Humayum fell while studying the stars; and near by is the splendid red sandstone mausoleum erected for him by his widow and his son Akbar. A century after its erection, this domed tomb of Humayum furnished the model for the Taj Mahal, and one quickly notes the main points of resemblance between this massive red building and the white dream at Agra. Humayum's tomb stands upon the same sort of high platform, but lacks the slender minarets at the corners. The red building and its white marble dome are larger than the more delicately modeled, the more ornate, poetic, and feminine structure at Agra. The last scene of the Mutiny was played here when Hobson's men overtook Bahadur Shah, the fugitive Delhi king, and returned the next day for the princes, shot them, and exposed their bodies in the blood-soaked, corpse-strewn Chandni Chauk. Bahadur Shah lived in exile at Rangoon for forty years, and his son, childless and born in exile, a harmless nonentity, was permitted to return to India for the durbar of 1903.

NE gets the full sense of antiquity in driving south from Delhi for eleven miles over a plain strewn with the ruins of seven earlier cities that preceded this modern Delhi, or Shah Jahanabad. Dwellings have crumbled away, but forts and tombs have withstood the ages, and there is a very feast of graveyards all the way to the Kutab minar. Hoariest of all the memorials is the carved stone column of Asoka (240 b.c.), inscribed with the Buddha's precepts against the taking of life, and which stands in Tughlak's ruined fort at Firozabad. At ruined Indrapat are the remains of the lovely inlaid mosque and the tall tower from which the emperor Humayum fell while studying the stars; and near by is the splendid red sandstone mausoleum erected for him by his widow and his son Akbar. A century after its erection, this domed tomb of Humayum furnished the model for the Taj Mahal, and one quickly notes the main points of resemblance between this massive red building and the white dream at Agra. Humayum's tomb stands upon the same sort of high platform, but lacks the slender minarets at the corners. The red building and its white marble dome are larger than the more delicately modeled, the more ornate, poetic, and feminine structure at Agra. The last scene of the Mutiny was played here when Hobson's men overtook Bahadur Shah, the fugitive Delhi king, and returned the next day for the princes, shot them, and exposed their bodies in the blood-soaked, corpse-strewn Chandni Chauk. Bahadur Shah lived in exile at Rangoon for forty years, and his son, childless and born in exile, a harmless nonentity, was permitted to return to India for the durbar of 1903.

At Humayum's tomb we left the tree-bordered Muttra road, where camel-wagons and strings of donkeys moved phantom-like through the dusty frost haze: the air so very sharp that one wondered how pipul- and tamarind-trees could retain their foliage. The revel of death and ruins, the feast of tombs and mortuary architecture, continued for miles, the names of the honored dead conveying no idea of personality, having no association of individuality to one, all this past so vague and unfamiliar that one moralizes, like Omar, on the vanity of man. One at last identifies four tombs—that of Akbar's brother, that of the Chisti saint, that of a Persian poet and that of the unhappy emperor Mohammed Shah, last occupant of the Peacock Throne so thoroughly despoiled by Nadir Shah. The saint, who was something of a juggler and miracle-worker, a Mohammedan mahatma, rests in a little white jewel-box of marble, whose red awnings give a comforting color-note to the chill court. The saint built a well guaranteed not to drown any one who leaped into it, and a lean boy in a tattered sheet begged us to see him jump. "One rupee—only one rupee, memsahib. Ek rupia." He fell, anna by anna, to half that price. We shivered in furs to think of a cold plunge in that icy air and keen wind, and finally bargained, in the presence of the priest, to give him six annas if he would go home, put on more clothes, and not jump that day. One crazy foreigner more or less, with notions crazier than the last one, could not disturb a molla; but as it was past his prophesying what we might not pay six annas for, in the course of our crass philanthropy, he himself conducted us about and to the tomb of Khusrau, "the sweet-singing parrot of India, memsahib." Khusrau was a Turk, but his Persian verses were so beautiful that Sadi made a pilgrimage from Persia to pay homage, and to this day all the gild of Delhi musicians and dancers remember him with garlands and bouquets. In this group of tombs is that of Jahanira, the daughter of Shah Jahan and Mumtaz-i-Mahal, who is a very real personage. Her years of devotion to her blind and captive father, her long life of piety and goodness, dying unmarried at the age of sixty-seven, warranted her burial in the Taj Mahal, or the Jama Masjid at Agra, built especially for her, rather than with that mixed but interesting company in the suburbs of Delhi.

The most beautiful tomb of them all is that of Mirza Jahangir, Akbar's son,—a platform of white marble supporting a white marble screen, with heavy doors of marble carved in low relief, likewise the lintels, cornice, and base—a dream of decoration, a symphony in white. Near by is another arrangement in white marble in low relief and latticework surrounding unhappy Mohammed, once the wearer of the Koh-i-nur and occupant of the Peacock Throne, who concealed the great diamond in his turban and then was courteously invited to change turbans by Nadir Shah. If ever death had beautiful and artistic recompense, "it is here, it is here, it is here," surely. Remembering the monstrosities of monuments and mausoleums in our Western graveyards, the broken columns, cremation urns, and misapplied Greek vase shapes that make our cemeteries places of horror, one wishes that committees on American public monuments and memorials might study these Indian tombs. Akbar's brother has also a marble sarcophagus carved in finest lacework, that rests under a great open pavilion, a marble canopy supported by sixty-four carved columns. While we stood enthusiastic by this exquisite tomb, comparing it with the domed sentry-box by the Hudson where lies America's greatest soldier, a piercing wail arose. A lone turban on a near roof was waving a yak-tail in air as the voice wailed so dismally. Soon black specks in the furthest sky defined themselves as hurrying bird-shapes, hovered like gigantic butterflies directly between us and the zenith sun, and whirled in prismatic beauty to our feet, a homing flock of pigeons. Like foot-soldiers, these winged creatures obeyed the voice and signals of their keeper, went through their evolutions, and caught the grain thrown in air. Afterward we recognized the

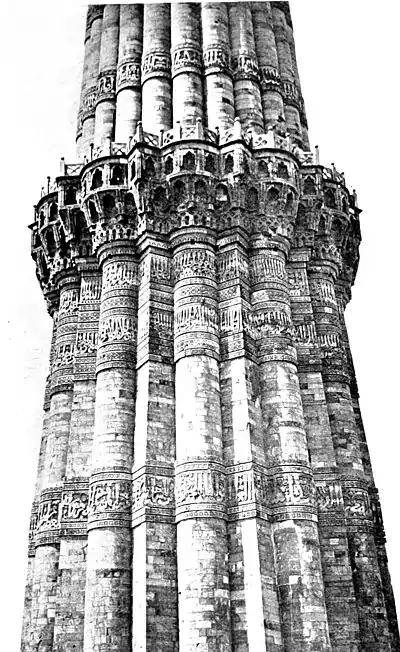

DETAIL OF KUTAB MINAR.

After five miles of temples, tombs, and graves we had had our fill of mortuary constructions, and, to the consternation of the bearer, refused to descend for Safdar Jang's tomb. "What, memsahib! Not see Safdar Jang? Everybody must see. Very nice tomb. Three-story place, that tomb. Gentries always go see that tomb." But we were obdurate. Safdar Jang was only the unlucky vizier of an inconspicuous Somebody Shah, and Fergusson had said that the mausoleum would "not bear close inspection."

All this time we were conscious of a slender, dark lance lifted against the sky-line. It was what we had come so far to see—the Kutab minar, one of the seven great sights of India, and certainly the most beautiful tower in the world. It grew as we advanced, until each angle, balcony, and band of lettering on its three red sandstone sections declared itself, and the flat, white marble sections at the summit were merged in inconspicuous perspective. This remarkable Kutab is emphatically such a departure from all the round or square towers ever seen that one has no wish to consider how it might have looked if constructed of one material throughout, or if the bands of ornament, the balconies, and the honeycomb work had been omitted. It is so richly decorated, it is itself so decorative, that at moments it seems as if it were only the fancy of a season, a mere World's Fair fantasy in staff or stucco, instead of a solidly built tower that has stood there for a thousand years, enduring earthquakes and sieges, and restorations by the later Moguls. One has to mount the roof of the mosque and see the great shaft at the level of its lowest bands of ornament to realize its size and the beauty and sharpness of those bold letters. One willingly traverses rubbish-heaps to do homage to the builder, Kutab-uddin, the Pathan ruler, who rose from slavery to the throne, and who, before the completion of his Tower of Victory, was laid away. One feels a personal loss and deprivation, too, that Ala-uddin, two centuries later, did not finish his great minaret, which would have repeated the Kutab on larger lines, and mounted five hundred feet in air,—twice the height of the Kutab,—the entire surface faced with carved stones. Viewing the Kutab at close range and from afar, one remembers pityingly the campaniles and giraldas, obelisks, spires, and pinnacles of the West. They used to do this thing so much better in India.

The Kutab is so entirely the thing at Old Delhi, that one lags in enthusiasm over the mosque, with its ruined arches and its hundred carved columns, spoil of Buddhist and Jain temples that the Pathans destroyed. To-day interest in the mosque court centers in the wrought-iron column, whose Sanskrit inscription dates back to the first century of our era. Native tourists flock to it as the great sight, and believe that if one reaches around the column backward and touches his hands together, good luck will follow him. The tomb of Altamsh, who built the mosque, and the one remaining gate of the court declare the scale of ornamentation that once covered all these crumbled walls and arches. Every inch of the roofless tomb is covered with carved ornament,—inscriptions, traceries, arabesques, and geometrical designs—the most ornamented mausoleum in India.

In the chilly, whitewashed vaults of the rest-house in the shadow of the Kutab, with dusty chicks to exclude any pernicious sunshine, we shivered over the cold, cold tiffin we had brought with us. Not hot bouillion nor hot chocolate could mitigate the death chill of that interior, or our interiors, and we hastened to drive with the wind four miles to the tomb of Tughlak. That massive, fortress-like place, of characteristic Egyptian solidity, was in extreme contrast to the highly ornamented tombs we had been seeing all day. The sloping walls and the entire absence of ornament came as a surprise, but the Pathan emperor has the ideal warrior's tomb. A crumbling wall half screens the ruins of his deserted capital of Tughlakabad, within which Tughlak's fortress is as Egyptian as his suburban tomb.

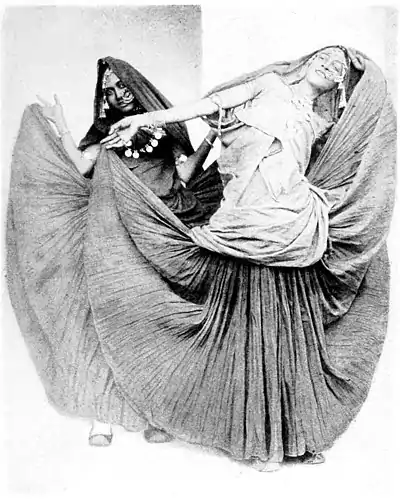

Some street-dancers pleaded with us at the hotel door, followed around and tapped on our windows, and we relented and moved the tea-table to the terrace, where it was really warmer than in the house. The two women, in cheap cottons and cheap jewelry, posed and whirled to a monotonous measure beaten on a skin drum. One woman gracefully carried a tiny child on her hip, or set it down on the cold flags, where it played contentedly with its fingers. Both dancers wore voluminous accordion-plaited skirts of red cotton, with yellow head-sheets patterned in red, and they were covered, as with breastplates, by many silver-coin necklaces. One dancer was a tall, sinuous creature, with a markedly Jewish or Egyptian face, who did the serpentine dance of Cairo cafés, and bent backward to pick up a rupee from the ground with her eyelids. Every step was marked by the jingle and clash of her bracelets and anklets, and this serpent of old Jumna, after one lively measure, paused and spread out her crinkled draperies in great butterfly-wings behind her in a "Loie Fuller pose" as old as Delhi. We had lamps and more lamps brought, eyes and turbans uncounted gathered in the dusk, and, inspired by native approval and tourist rupees, the skirt dance went on through many figures.

We sent runners to find them the next morning. We wanted them to dance at noon, that we might turn a battery of kodaks upon them. "Those are very poor, common dancers," said the bearer, scornfully. "I will get very splendid nautches, in silk and kincob saris and very splendid jewels, in 'niklasses' and 'griddles' of rubies and pearls." But we wanted only those same dancers in their cheap clothes and silver necklaces and girdles; and it took insistence to get them. They came; and in the sunlight their silver and glass, brass and lac jewelry were as gems, and our enthusiasm was greater than that of the night before. They danced their best, held their poses interminably for the time exposures, and we reeled film away so recklessly that the hotel manager said: "Oh, madam, if you have so many plates to spare, won't you take my baby?"

STREET DANCERS, DELHI.