CHAPTER XVI

DELHI

T was in the regular order of discomfort that we should leave Agra late at night and reach Delhi at four o'clock in the morning; the last straw lay in the fact that we departed in a pouring rain and made the midnight change at Tundla Junction in a cloud-burst. Fires had warmed the rooms (which we reached by a roof or terrace) when we arrived at the much commended Delhi hotel, and we fell asleep to dream of Madura noondays until an unusual hour of the morning. Then we found that the rooms had no windows, so that when the doors were closed and the fire-places heaped with wood, we had easily enjoyed the climate of the tropics. That hotel, named for a great viceroy, was by far the worst, the most forlorn, run-down, and dilapidated of any we found up-country. The drawing-room was a muddle of broken furniture, of dusty and disorderly draperies, the dining-room infragrant and time-stained, and the manager—there are no landlords or innkeepers in British realms any more—a listless, depressed, poor white creature, a definite failure in life, who roamed the portico in pajamas and long ulster, smoking a German student pipe. We removed forthwith to another hotel, that had once been a splendid official residence. Our rooms opened by long windows upon a cement terrace flush with the battlements of the city walls, and from that high parapet we looked down upon the Jumna and green wooded spaces where the jackals howled all night and wherein are laid some of the scenes of "On the Face of the Waters." The entrance portico of the mansion was used as a dining-room, the great stone arches partly closed at night by bamboo blinds, ventilated curtains that swayed and swung in the drafts and breezes which blew over us as we dined there, practically out of doors, on those cold January nights, with the humidity great and the thermometer registering 38 to 40 degrees.

T was in the regular order of discomfort that we should leave Agra late at night and reach Delhi at four o'clock in the morning; the last straw lay in the fact that we departed in a pouring rain and made the midnight change at Tundla Junction in a cloud-burst. Fires had warmed the rooms (which we reached by a roof or terrace) when we arrived at the much commended Delhi hotel, and we fell asleep to dream of Madura noondays until an unusual hour of the morning. Then we found that the rooms had no windows, so that when the doors were closed and the fire-places heaped with wood, we had easily enjoyed the climate of the tropics. That hotel, named for a great viceroy, was by far the worst, the most forlorn, run-down, and dilapidated of any we found up-country. The drawing-room was a muddle of broken furniture, of dusty and disorderly draperies, the dining-room infragrant and time-stained, and the manager—there are no landlords or innkeepers in British realms any more—a listless, depressed, poor white creature, a definite failure in life, who roamed the portico in pajamas and long ulster, smoking a German student pipe. We removed forthwith to another hotel, that had once been a splendid official residence. Our rooms opened by long windows upon a cement terrace flush with the battlements of the city walls, and from that high parapet we looked down upon the Jumna and green wooded spaces where the jackals howled all night and wherein are laid some of the scenes of "On the Face of the Waters." The entrance portico of the mansion was used as a dining-room, the great stone arches partly closed at night by bamboo blinds, ventilated curtains that swayed and swung in the drafts and breezes which blew over us as we dined there, practically out of doors, on those cold January nights, with the humidity great and the thermometer registering 38 to 40 degrees.

"It is a land of misery," cried a great American litterateur who was doing India with a rapidity unequaled by any personally conducted tourist. "All I want to do is to get out of it; to get away; to get something an American stomach is used to eating; to get some Apollinaris instead of this hygienic soda; to get warm again. If I get within one hundred miles of any place, I will say I have seen it. I don't want any more architecture at this price." And this tirade was in the same key and vein indulged in by all the coughing, sneezing, rheumatic, and neuralgic tourists. All were cross, half ill, and thoroughly homesick in this chill land of supposed tropic splendors.

When the sour mists or the frost hazes of those Delhi mornings had cleared away, we had sunshine that mellowed grumblers to amiability, and they basked in the hot beams of noonday; but gloom settled on them with the damp chill of sunset, and there were the same depressed and depressing groups huddled before the few hissing twigs in the fireplaces of the chill white caves of rooms. Then the jackals came under our windows and laughed and shrieked hysterically, as well they might, at calling such a tour pleasure travel.

The old capital of the Moguls has great charm in sunshine, and Delhi's main thoroughfare, the Chandni Chauk (Silver Square), was the most brilliant and spectacular place we had seen. All native life was crowded into that street, which is a continuous market-place for a mile, with rainbow crowds of people streaming up and down, buying and selling everything from crown diamonds and jeweled jade to sheepskins and raw meat. The street has run with blood many times, and has been strewn and stacked with corpses. Nadir Shah put one hundred thousand to death, Timur had done worse, and the Mahrattas were the worst of all; so that the butchery after the Mutiny siege of Delhi was but another regrettable incident in its history. At the far end of the street towers the red sandstone gateway of Shah Jahan's fort, and driving in under this portal fit for kings and triumphal armies, we found sepoys lounging on charpoys by the guard-house door, tunics unbuttoned, turbans awry and at loose ends, and Moslem shoes hanging from one bare toe—the sans gêne of the race undisturbed by the noble environment or the contrasting presence of the tramping sentry on duty, turbaned and accoutred to perfection, spindle legs wound with smooth putties, and the enormous English shoes blacked to a drill-sergeant's dream. Such loungers at the guard-house door are on view at every show fort and palace in India, incongruous, disillusioning, but thereby the real thing. Incongruity is the regular order in India, splendor and shabbiness, dirt and riches, luxury and squalor always going together. We were free to roam the courts and garden spaces of the palace unhindered, from Shah Jahan's open audience-hall, or music-room, with its panels of Florentine mosaic on black marble ground, to that inner throne-room, the most splendid in the world. This peerless Diwan-i-Khas, one mass of rich decoration from the inlaid floor to the golden ceiling, was worthy setting for the Peacock Throne. The renegade Frenchman or Italian who planned the palaces of Shah Jahan, and the skilled workmen brought from all the centers of Mohammedan luxury, made the Delhi palace equal in decorative details to the Agra palace and the Taj. "If there is on earth an Eden of bliss, it is this, it is this, it is this," was appropriately inlaid in Persian letters in this throne-room, whose square columns, arches, spandrils, frieze, and moldings are decorated with exquisite pietra dura. A small dais shows where stood the Peacock Throne, that low, square chair completely sheathed in rubies, pearls, diamonds, emeralds, and other stones, the Koh-i-nur one of the peacock's eyes, and a life-sized parrot cut from a single emerald its crowning ornament. That fabled emerald parrot, like the so-called emerald Buddha at Bangkok, was undoubtedly nothing but a very fine and clear piece of fei tsui jade, but it went with all the other loot that Nadir Shah carried away in 1739—loot the value of which amounted to thirty-eight million pounds, and which was scattered by the Kurds when he was murdered. India was drained of its riches then, for no good end. After Nadir Shah had gone his way with the Peacock and nine other jeweled thrones, this palace suffered neglect as well as sacking. When Lord Auckland's sisters saw it in 1838, the old King of Delhi sat in a neglected garden, his own dirty soldiers lounged on dirty charpoys in the beautiful inlaid bath-rooms, and the precious inlays were being stolen, bit by bit, from the rooms of the princes. One regrets the destruction that followed the Mutiny, when the zenana and whole labyrinths of guest-rooms were torn away to make space for barracks. Sir James Fergusson has dealt with these destroying British barbarians very thoroughly in "Indian and Eastern Architecture" (Vol. II, p. 208), and hands on to immortality the name of Sir John Jones, who tore up the platform of the Peacock Throne and divided it into sections which he sold as table-tops, the pair now in the India Museum at London having fetched him five hundred pounds.

The audience-halls, the baths, and the rooms around the Diwan-i-Khas were repaired and restored at great expense in preparation for the Prince of Wales's visit in 1876, and close watchfulness has maintained them in that condition. One can only wish that for completeness' sake a glass copy of the Peacock Throne might be installed in the original's place. Tourists would gladly contribute their annas to that worthy end.

The Jama Masjid, the largest and certainly the most imposing mosque in India, lifts its minarets across a great park where troops of great apes race madly, alert for the pious Hindus, whom one often sees ostentatiously feeding them inferior boiled rice, "to acquire merit." The great gateway of the mosque, high on a terraced platform, is second only to Akbar's Gate of Victory, and, opening formerly only for the Mogul emperor, swings widely now when the Viceroy visits it. On Friday mornings ten and twelve thousand people worship there; in festival times four times as many assemble. The priests are friendly, and in one of the lesser minarets show one richly illuminated copies of the Koran, Mohammed's slipper filled with jasmine blossoms, and finally one henna-red hair from the beard of the Prophet. There is a busy market around the steps of the great gateway on certain days, when grotesque two-story camel-wagons bring in country produce; dealers in poultry hold one side of the terrace steps and bird-fanciers the other. We had eaten mutton-chops from Tuticorin northward, but had never seen a live sheep until we heard its familiar voice by Jama Masjid's steps. But what flocks of goats we had seen in pastures, on country roads and city streets! "It is poultry," said the bearer as we regarded the fat-tailed sheep with curiosity, his application of

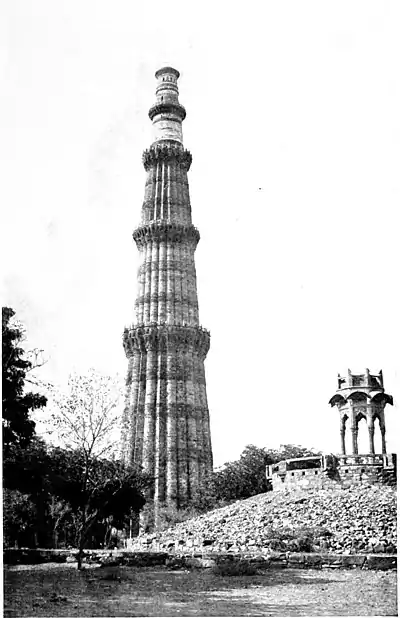

KUTAB MINAR

The little Jain temple and the Black Temple of the Hindus are sanctuaries of other Delhi sects, but we forgot conventional sights and the rivalry of religions when we met a wedding procession in the labyrinth of streets in that quarter. The horses wore gold, silver, and jeweled bridles, head-stalls and necklaces to match, and gold-embroidered cloths and trappings. The bridegroom's brother was a dazzling, kincob-clad person, jeweled to distraction, with wreaths and tassels of jasmine covering him from crown to waist, and the bridegroom was twice as splendid. The populace gaped and ran after the cavalcade, and half-naked beggars tiocked with extended palms. "Jao! Jao!" said the bridegroom's brother in a voice to make a policeman tremble; and swish! came his jeweled whip on the bare shoulders of one insistent petitioner. With a yelp of pain and a spiritless whine, the beggar slunk away.

Delhi remains the center of all Indian art industries. The most skilful jewelers and gem-cutters, painters, carvers, embroiderers, and craftsmen whose creations could tempt the purse or minister to the luxury of the greater and lesser Moguls, have gathered there for centuries, and trade habits are but slowly broken. Along Chandni Chauk plump merchants in snow-white clothes and tiny jeweler's turbans invite one to their white, washed, felt-floored inner rooms; and there, treading cat-like in stockinged feet, they unroll gold and silver embroideries, Kashmir shawls, and "camble's-hair" stuffs, and cover the last inches of floor space with jewels. Necklaces, girdles, and a queen's ornaments are drawn from battered boxes, scraps of paper, cotton cloth, or old flannel. Nothing seems quite as incongruous in this land of the misfit and the incongruous as the way in which the jewels of a raja are produced from old biscuit-tins, pickle-bottles, and marmalade-jars. One buys the gems of a temple goddess, and they are laid in grimy cotton-wool and packed in rusty little tin boxes of a crudity inconceivable. While on the claim the Klondike miner considers the makeshift of a baking-powder box, as a safe deposit for his nuggets and dust, as a huge joke; but the Hindu jeweler does it with no sense of the unfitness of things, of relative propriety in splendor. "Memsahib does not like tin box? Very well. See!" and the ruby necklace was wrapped in a bit of newspaper, and put in a broken pasteboard box that had held a druggist's prescription. When they have covered the floor with their most valuable stuffs, the shopmen walk over them without compunction, pull them here and there, and throw them in heaps into the corners. When this happens several times a day, and the traps are bundled to and from the hotels night and morning, it is small wonder that everything offered one is mussy, wrinkled, and shop-worn. Despite the lures and promises of the toy turban tribe, no important pieces of carved or jeweled jade were seen. To them any green stone was jade, and under that name they brought out serpentine, bowenite, and chloro-melanite—anything soft and easily worked that would look as well. Three generations of one family are no longer employed in carving one jade bowl, as in Mogul times. Art is fleeting now, and the lapidaries want quick sales and as large returns as the tourist's enlightenment permits.

One may handle these Delhi jewels by the hour and not see a flawless stone, a spherical pearl, or any string of pearls matched perfectly in size, shape, skin, or luster; and one moves in and breathes such an atmosphere of jewels in Delhi that he soon regards precious stones as the usual, serious accompaniment of daily life. A prosaic tourist, never given to such weaknesses, soon finds himself hanging and haggling over jewels, buying unset stones and gewgaws to indiscretion. From the earliest breakfast hour to the last home-coming at dusk, and until the train bears him away from the station platform, open jewel-boxes and rows of necklaces spread on cloths or shawl-ends are put before him. Some insinuating Lal This or Lal That, with caste-marked brow and tiny turban, is always salaaming and begging him to buy his blue ferozees (turquoises), or necklaces of the nine lucky stones. A tap at the door, and it opens to show a brown face and a tassel of necklaces swinging from a brown hand; and in time the victim is hypnotized by the glittering objects. There is bitter trade rivalry among the jewelers and their touts, and one cannot visit the shop or buy of one of the Lals without being denounced and upbraided for partiality by all the other Lals. "Please come my shop. Please buy my shop. I am only honest man. I am poor man," said one oily tongue, putting his fingers to his mouth in dumb show of rice-eating. "Yes, yes," we said to the importunate as we drove away from the hotel, and a fierce-eyed, viperish-looking Hindu made a flying leap to the other step of the carriage and hissed: "Don't go his shop. He is bad man. He cheat. He lie. His ferozees are all glass, chalk. I speak true. I am honest man. I have true stones. I am poor man. Please buy my shop." An emphatic "Jao!" made him drop away from the carriage step. Winding up his loose end of red shawl, he went back to the door-step and squatted there in apparent fraternity with the wicked rival—both blood-brothers in lying and cheating, both waiting for fresh prey, the tourist the righteous victim for such swindlers in all countries.

After much looking and comparing, a friend of that Indian winter bought a ruby necklace, and as she stowed it away in her inside strong pocket her particular Lal said, "Please, ladyship, do not show any one here in Delhi. Let no man know that I have sold, that you have bought my 'niklass.' Those bad fellows at hotel do something if they know I sell." We strolled for an hour along the Chandni Chauk, when we were met by our servant with a closed carriage and drove to the Ridge. As the horses slowed down for the long hill climb, the box was opened for a look at the new purchase. Hardly had the owner wound it over her hand, when the kincob turban and viper countenance of the rival jeweler was thrust in the open window. There was an "Ah" of such venomous rage that we screamed in alarm. The head vanished, and this sleuth-hound of jewelers, who had shadowed us all day and clung to the back of the carriage, was seen speeding like a deer back to the city.

"Oh, I found Delhi so sad, so depressing. All those scenes of the Mutiny, you know—the Kashmir Gate and the Ridge, don't you know. It was so terrible that I was really glad to get away," said an English visitor. The ruby collar and the detective jeweler had put us beyond any depression incident to the visit to the Ridge, familiar as is its history when one has read Lord Roberts's "Forty-one Years in India" and Mrs. Steele's "On the Face of the Waters." At Delhi, too, one feels that there have been too many sieges and reliefs in these later days for the events of 1857 to be dinned into one quite so endlessly. Newspaper readers are all strategical experts now, and they balance and measure the horrors and heroisms of the siege of Delhi against the modern ones; match the storming of the Kashmir Gate with the glorious storming of the South Gate of Tientsin and of the East Gate of Peking by the Japanese in the China campaign of 1900.

From the Ridge one looks down upon the great plain where the annual camp of exercise, or the great military manœuvers, are held each year. The great durbar or Delhi meeting of 1877 was held on this same plain, when Lord Lytton proclaimed the Queen of England as Empress of India in the presence of all the feudatory princes and an assemblage of more than one hundred thousand people. The plain was the scene also of the greater durbar of 1903, when Lord Curzon proclaimed King Edward VII of England as Emperor of India, with a pageantry and splendor unapproached in modern times,—the most magnificent state ceremony that has ever been seen.