|

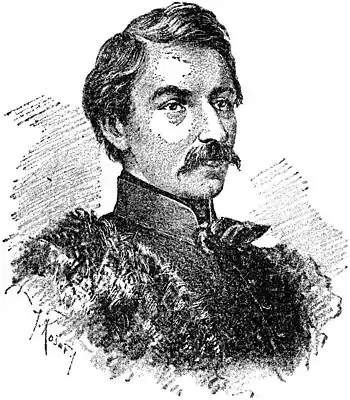

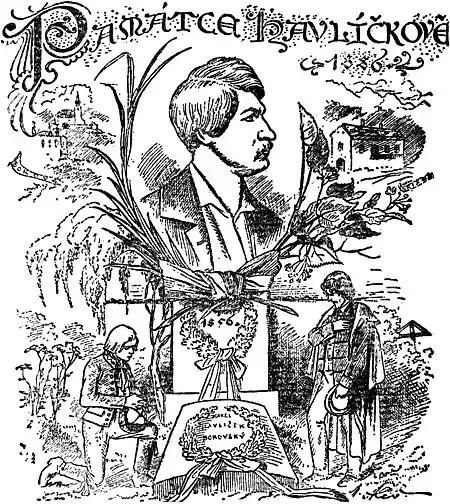

Karel Havlíček. (1821—1856.)

On Chicago’s near southwest side, in the Douglas Park, stands a beautiful statue of a man whom the Czech nation came to regard as their hero and martyr and who within a brief space of time allotted to him has by his literary work contributed most efficiently towards the liberation of Czechs from the fetters of Austrian tyranny. Thus he became a direct precursor of the revolutionary movement for the Czech and Slovak independence which during the World War has culminated in the political and diplomatic activities of Professor T. G. Masaryk, since 1918 the first President of the newly created Czechoslovak Republic.

It is, indeed, not a mere coincidence that Masaryk ever since has maintained a very close and intimate relation toward the founder of Czech national journalism and the extraordinarily gifted poet. One of Masaryk’s early writings, published in 1896, deals with the strong personality of Karel Havlíček who, both prior to and after the March revolution of 1848, fought many a gallant and victorious battle with the Austrian bureaucracy and the absolutist régime of the Vienna government for his ideals of the political awakening of the Czech nation, till he finally fell a victim to the stupidity of the Habsburg police and died, broken in heart and body, at the early age of 35 years.

Karel Havlíček was born October 31, 1821, in the village of Borová near the city of Přibyslava in Bohemia. After his graduation from the classical gymnasium in Německý Brod he went with his family to Prague where he enrolled in the University as student of philosophy and later on of Catholic theology; but having been dismissed from the school of divinity on account of his rather radical and advanced views he devoted all his energy to a literary career, and began to spend most of his time for a thorough study of Slavonic languages, especially of Russian and Polish, and finally went to Russia as private tutor where he spent two years (1843 to 1844). A keen observer and analytical critic of the conditions in the land of czars, he soon abandoned his original russophile enthusiasm, but, at the same time, undertook an exhaustive study of the contemporary Russian literature and was deeply impressed by the lucid and vivid realism of Nikolaj Gogol of which he soon became the first herald in the Czech literature: as early as 1849 he translated Gogol’s novel "Dead souls". After his return to Austria Havlíček was appointed editor of two papers “Pražské noviny” (Prague News) and “Česká včela” (Bohemian Bee) which under his able leadership from tame official organs were transformed into a liberal paper which soon became “the conscience of the whole nation” and the best critical and literary review of his time, respectively. Later, having left the editorship of the governmental papers, he became editor and publisher first of Národní Noviny” (National News) which paper, although it was stopped by the Austrian government after several months, was properly considered the most popular mouthpiece of the politically awakened Czech nation, and later of “Slovan” which fearlessly fought against the hydra of reaction. But the Austrian government decided to break the indomitable spirit of Karel Havlíček, and in 1852 deported him to a very unhealthy spot in Tyrol, to a little village of Brixen where he contracted tuberculosis. When after three years, in 1855, he was allowed to come back to Bohemia, he found that in the meantime his beloved wife had died, and he himself was mortally ill. Unable to find any relief in his affiction, he died July 29. 1856 in Prague. His funeral, in spite of the severest reactionary measures of the absolutist regime of Bach, became an eloquent manifestation of love and admiration for the political martyr.

Havlíček was not only a political writer and publicist, he was also an unusually talented poet. His first attemps at poetry did not go beyond the pathetic and elegiac patriotism of his time, but soon, especially after his return from Russia, he discovered his real poetic vein. He became the most exclusive satirist, caricaturist and humorist in the Czech literature, who, perhaps with more accomplished skill than just before him the poet František Ladislav Čelakovský, found his quite individual style in a close imitation of the folk-song and who, as the greatest Czech critic F. X. Šalda, stresses, “very happily based his poetic intuition upon all its rythmical and logical possibilities of intonation and expression.”

Besides a considerable number of sharp and witty epigrams Havlíček composed three longer poems of an imperishable value. First between 1848—1854 he wrote the brilliant satire of the Russian absolutism and religion, the “Křest sv. Vladimíra” (The Baptism of St. Vladimir) (translated into English by Ernest Altschul in Cleveland 1930), which first appeared in complete form 1870, fourteen years after its author’s death. In 1852 were conceived and in 1860 and 1861 published in book form the “Tyrolean elegies”, depicting in a half humoristic, half satirical mood Havlíček’s deportation to his involuntary exile in Brixen. Altough upon the surface there appears a light spirit of mockery and bravado, upon more intent listening we are able to discern some striking undertones of a sad and at times even desperate feeling. As third of the longer poems there was written in 1854 and published in 1870 “Král Lavra” (King Lavra) which in a popular form offers a version of the classical Midas story.

As a poet Havlíček broke with the oversweetened patriotic poetry of romanticism and laid the foundations of Czech literary realism which was brought to a perfection by Jan Neruda.

Dr. John J. Reichman.

I.

Shine fair moon-beam, shine but lightly

Through the cloudy height;

Tell me, how do you like Brixen?

Why so mean tonight?

Do not hurry; pause a little;

Don’t go yet to rest,

Let me talk with you a little,

Listen to my quest.

That I am not local, moon-beam,

You know by my speech;

Not a “true and upright” native,

List to what I preach.

II.

I am from a land of music,

Where I played the horn,

And my music, in Vienna,

Woke the masters’ scorn.

And since, when their work was over,

They wanted to rest,

One dark night they sent for me

A carriage with their best.

It was two hours past midnight,

Edging on to three,

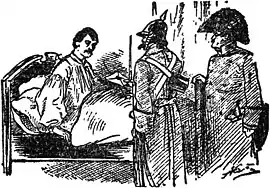

When a gendarme at my bedstead

Said “good-day” to me.

And with him the whole ensemble,

A court in full parade,

Gold upon their rigid collars,

’round their waists gold-braid.

“Mister editor, awaken,

Entertain no fear,

Though ’tis night, we are no robbers;

This what brings us here.

From Vienna, happy greetings,

From Sir Bach—but this—

Are you well? And this sealed letter

He sends you with a kiss.”

Even on an empty stomach

I am most polite.

“Pardon me, you royal servants,

This shirt I wear at night.”

But old Jack, my coal-black bulldog,

Lacks all sense of mirth

He knows “habeas corpus” only

Through his English birth.

viť, měsíčku, polehoučku

skrz ten hustý mrak:

jak pak se ti Brixen líbí?

Neškareď se tak!

So he almost made a blunder,

Broke a rule or two

As he growled beneath the bedstead

At the royal retinue.

But I trew at him a volume

Of our monarchic laws;

And he growled no more that evening

Without any cause.

III.

I am used to rule and order;

Since it was December,

I put on my woolly stockings

Aided by each member.

Afterwards I read the letter—

There ’tis on the shelf,

If you know official German,

Read it for yourself.

Bach advises as a doctor,

That the raw Czech air

Is not healthy, and ’tis better

That I move from there;

That the Czech clime is too sultry,

Full of steaming mists,

And ill smelling regulations,

Other ills he lists.

That is why he sent for me

A carriage in full haste,

That I travel as a state’s guest,

With no time to waste.

And the gendarmes have instructions

How to urge and nudge

If in my known modest nature

I’d refuse to budge.

IV.

What could I do in this instance?

Since it was my way

To obey the well-armed gendarmes

And do as they’d say.

Dedera was also urging

That I should decide,

Else, at daybreak other townsmen

Too would want to ride.

And he told me that no weapons

Need I take along.

For, as ordered, they’d defend me

From all harm and wrong.

Further, that an incognito

I maintain at best,

Or the Czechs, intruding people,

Would give us no rest.

Dedera gave me some other

Well-meant wise advice,

To be followed by Bach’s patients

At no added price.

Thus he coaxed me as a Siren,

And as in a trance,

I found shoes, took vest and frock coat,

First of all, my pants.

And the gendarmes with their horses

Stood before the hut,

“Patience have a while, my brothers,

Soon now we shall trot.”

V.

But, old moon, you know these women,

Know them through and through,

Know what troubles man has with them,

What is best to do . . .

Many farewells you've witnessed,

In your secret way,

Bitterness of parting moments

You can best portray.

Mother, sister, wife and daughter,

Zdenka, little tot,

Stood about, all softly weeping,

O’er my bitter lot.

Though I am a seasoned cossack,

Tried in many frays,

Something gripped my chest that moment,

Something dimmed my gaze.

So I pulled my fur cap downward

Simulating cheer

Lest the gendarmes should discover

In my eyes a tear.

For the gendarmes, near the doorway,

Stood as guard, erect,

That the parting scene might have

An imperial effect.

VI.

Blares the bugle . . . wheels are rattling

Toward Iglau we ride,

To prevent our losing something

Gendarmes trot beside.

On the hill, the Borov Chapel

Stands alone and sad,

Looking at me through the forests:

“Is it you, my lad?

Under me, your cradle rested,

You were baptized too,

Here I saw the aged vicar,

Teach you all he knew.

Through the world I saw you wander

With a faggot bright,

Saw you cast before your people

A jolly stream of light.

How the time has passed ? I know you

Now for thirty years . . .

But my boy, what queerly monster

At your side appears?”

VII.

As we rode through sleeping Iglau,

Spilberg filled my mind,

And past Lintz, but thoughts of Kufstein

Seemed to wind and wind.

And not till we left old Kufstein

Standing on our right,

Did I see the Alpine country

In a more pleasing light.

It’s a foolish ride, dear fellow,

When you know not where.

The postillion’s glad bugle

Is a shammed affair.

Axle grease at every station,

And exchange of teams:

It were better if Vienna greased

And changed, it seems.

I discovered the good uses

Of the telegraph,

For it heralded our coming

In a lengthy paragraph.

The police, as a doting mother,

Everywhere we drove,

Was prepared for our coming

With a heated stove.

But lest I forget, at Budweiss

Where we stopped to dine,

Dedera bought four stout bottles

Of old Melnik wine.

Was it patriotic feeling,

Moved his thought and hand?

Or hoped he it was the Lethe

From my native land.

Melnik wine I’ve long forgotten

Drink Italian now,

But it seems same restless ferment

Is in both somehow.

VIII.

Now, dear moon, the elegy forgetting,

Let us pass to a heroic vein

For the story I will now narrate you

Has a very diabolic strain.

There’s a road from Reichenhall to Weidring,

You know well the road I mean, perchance,

This cannot be passed through simple passage

Of a legal form of ordinance.

Cliffs and mountains reaching even higher

Than the quarrels that 'twixt nations soar,

And along the road a baseless abyss,

Gaping as when army cannons roar.

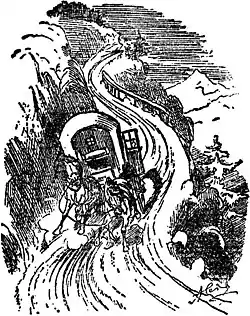

Through the night as dark as church, our mother,

Down the hill we ride, a wink-like feat;

Vainly Dedera shouts: “Hold the horses!”

No one’s in the seat.

Our carriage creaks; wild are the horses;

Devil drives them over hill and plain,

While the driver somewhere round the hillside

Lights his pipe again.

Steep the road, inclined as a church steeple,

As an arrow, glides our coach o’er this,

Perphaps planning to intern us yonder

In the deep abyss.

Ah, for me it was a pleasant moment,

For in life I know no such delight

Than to see our glorified policemen

Trembling with fright.

I recalled then—for I read the Bible—

Jonah’s sad, but necessary fate,

When from off the boat he was ejected

The stormy seas to sate.

“Let us toss a lot”, I said. “Among us

Is a sinner worthy of reproach,

And to pacify the skies, this sinner

Must leap from out the coach.”

I no sooner spoke, behold the gendarmes

Without waiting burdened souls to pry,

Penitently breaking through the doorway,

Out the coach they fly.

Oh you ages, topsy turvy ages,

In the ditch the guards lie upside down,

While the equipage with its delinquent

Rides alone to town.

Oh you powers, topsy turvy powers,

You who would lead nations by a rope,

While you’re helpless, with a team of horses

Without reins, to cope.

Without driver, without reins, sheer darkness,

At my side a gulf that steeper grows,

Thus alone I galloped in the carriage

As the Alp wind blows.

Should I fear to trust my Fate and body

To a team of horses, run-away?

Wha can happen to an Austrian subject

That is worse, I pray?

In my head but coolest resignation,

’twixt my lips a smoking hot cigar,

Faster than a Russian Czar I landed

At the post, not far.

As a delinquent most examplary

Then without protection I have dined,

Ere the guards with skinned and bloody noses

Limped in from behind.

I slept well in Weidring, but the gendarmes

Spent a most uncomfortable night,

Rubbed with alcohol their backs and noses,

Easing thus their plight.

And here ends my lengthy, truthful epic,

To which I have added not a drop,

To this day in Weidring you can hear it,

From Postmaster Dahlrupp.

IX.

Finally we came to Brixen

With no further worry,

And they gave Dedera, for me

Receipt in a hurry.

And to Czech, this piece of paper

They returned because

Here, the double-headed eagle

Holds me in his claws.

Gendarmes and a district ruler

In this barren area,

They gave me for guardian angels

In this Siberia.

| Original: | This work was published before January 1, 1927, and is in the public domain worldwide because the author died at least 100 years ago. |

|---|---|

| Translation: | This work is in the public domain in the United States because it was legally published within the United States (or the United Nations Headquarters in New York subject to Section 7 of the United States Headquarters Agreement) between 1923 and 1977 (inclusive) without a copyright notice. |