XII

CULLY'S NIGHT OUT

EVER since the night Cully, with the news of the hair-breadth escape of the bid, had dashed back to Tom, waiting around the corner, he had been the hero of the hour. As she listened to his description of McGaw when her bid dropped on the table—“Lookin' like he'd eat sumpin' he couldn't swaller—see?” her face was radiant, and her sides shook with laughter. She had counted upon McGaw falling into her trap, and she was delighted over the success of her experiment. Tom had once before caught him raising a bid when he discovered that but one had been offered.

In recognition of these valuable services Tom had given Cully two tickets for a circus which was then charming the inhabitants of New Brighton, a mile or more away, and he and Carl were going the following night. Mr. Finnegan was to wear a black sack-coat, a derby hat, and a white shirt which Jennie, in the goodness of her heart, had ironed for him herself. She had also ironed a scarf of Carl's, and had laid it on the window-sill of the outer kitchen, where Cully might find it as he passed by.

The walks home from church were now about the only chance the lovers had of being together. Almost every day Carl was off with the teams. When he did come home in working hours he would take his dinner with the men and boys in the outer kitchen. Jennie sometimes waited on them, but he rarely spoke to her as she passed in and out, except with his eyes.

When Cully handed him the scarf, Carl had already dressed himself in his best clothes, producing so marked a change in the outward appearance of the young Swede that Cully in his admiration pronounced him “out o' sight.”

Cully's metamorphosis was even more complete than Carl's. Now that the warm spring days were approaching, Mr. Finnegan had decided that his superabundant locks were unseasonable, and had therefore had his hair cropped close to his scalp, showing here and there a white scar, the record of some former scrimmage. Reaching to the edge of each ear was a collar as stiff as pasteboard. His derby was tilted over his left eyebrow, shading a face brimming over with fun and expectancy. Below this was a vermilion-colored necktie and a black coat and trousers. His shoes sported three coats of blacking, which only partly concealed the dust-marks of his profession.

“Hully gee, Carl! but de circus's a-goin' ter be a dandy,” he called out in delight, as he patted a double shuffle with his feet. “I see de picters on de fence when I come from de ferry. Dere's a chariot-race out o' sight, an' a' elephant what stands on 'is head. Hold on till I see ef de Big Gray 's got enough beddin' under him. He wuz awful stiff dis mornin' when I helped him up.” Cully never went to bed without seeing the Gray first made comfortable for the night.

The two young fellows saw all the sights, and after filling their pockets with peanuts and themselves with pink lemonade, took their seats at last under the canvas roof, where they waited impatiently for the performance to begin.

The only departure from the ordinary routine was Cully's instant acceptance of the clown's challenge to ride the trick mule, and his winning the wager amid the plaudits of the audience, after a rough-and-tumble scramble in the sawdust, sticking so tight to his back that a bystander remarked that the only way to get the boy off would be to “peel the mule.”

When they returned it was nearly midnight. Cully had taken off his “choker,” as he called it, and had curled it outside his hat, They had walked over from the show, and the tight clutch of the collar greatly interfered with Cully's discussion of the wonderful things he had seen. Besides, the mule had ruined it completely for a second use.

It was a warm night for early spring, and Carl had his coat over his arm. When they reached the outer stable fence—the one nearest the village—Cully's keen nose scented a peculiar odor. “Who's been a breakin' de lamp round here, Carl?” he asked, sniffing close to the ground. “Holy smoke! Look at de light in de stable—sumpin' mus' be de matter wid de Big Gray, or de ole woman wouldn't be out dis time o' night wid a lamp. What would she be a-doin' out here, anyway?” he exclaimed in a sudden anxious tone. “Dis ain't de road from de house. Hully gee! Look out for yer coat! De rails is a-soakin' wid ker'sene!”

At this moment a little flame shot out of the window over the Big Gray's head and licked its way up the siding, followed by a column of smoke which burst through the door in the hay-loft above the stalls of the three horses next the bedroom of Carl and Cully. A window was hastily opened in Tom's house and a frightened shriek broke the stillness of the night. It was Jennie's voice, and it had a tone of something besides alarm.

What the sight of the fire had paralyzed in Carl, the voice awoke.

“No, no! I here—I safe, Jan!” he cried, clearing the fence with a bound.

Cully did not hear Jennie. He saw only the curling flames over the Big Gray's head. As he dashed down the slope he kept muttering the old horse's pet names, catching his breath, and calling to Carl, “Save de Gray—save Ole Blowhard!”

Cully reached the stable first, smashed the padlock with a shovel, and rushed into the Gray's stall. Carl seized a horse-bucket, and began sousing the window-sills of the harness-room, where the fire was hottest.

By this time the whole house was aroused. Tom, dazed by the sudden awakening, with her ulster thrown about her shoulders, stood barefooted on the porch. Jennie was still at the window, sobbing as if her heart would break, now that Carl was safe. Patsy had crawled out of his low crib by his mother's bed, and was stumbling downstairs, one foot at a time. Twice had Cully tried to drag the old horse clear of his stall, and twice had he fallen back for fresh air. Then came a smothered cry from inside the blinding smoke, a burst of flame lighting up the stable, and the Big Gray was pushed out, his head wrapped in Carl's coat, the Swede pressing behind, Cully coaxing him on, his arms around the horse's neck.

Hardly had the Big Gray cleared the stable when the roof of the small extension fell, and a great burst of flame shot up into the night air. All hope of rescuing the other two horses was now gone.

Tom did not stand long dazed and bewildered. In a twinkling she had drawn on a pair of men's boots over her bare feet, buckled her ulster over her night-dress, and rushed back upstairs to drag the blankets from the beds. Laden with these she sprang down the steps, called to Jennie to follow, soaked the bedding in the water-trough, and, picking up the dripping mass, carried it to Carl and Cully, who, now that the Gray was safely tied to the kitchen porch, were on the roof of the tool-house, fighting the sparks that fell on the shingles.

By this time the neighbors began to arrive from the tenements. Tom took charge of every man as soon as he got his breath, stationed two at the pump-handle, and formed a line of bucket-passers from the water-trough to Carl and Cully, who were spreading the blankets on the roof. The heat now was terrific; Carl had to shield his face with his sleeve as he threw the water. Cully lay flat on the shingles, holding to the steaming blankets, and directing Carl's buckets with his outstretched finger when some greater spark lodged and gained headway. If they could keep these burning brands under until the heat had spent itself, they could perhaps save the tool-house and the larger stable.

All this time Patsy had stood on the porch where Tom had left him hanging over the railing wrapped in Jennie's shawl. He was not to move until she came for him: she wanted him out of the way of trampling feet. Now and then she would turn anxiously, catch sight of his wizened face dazed with fright, wave her hand to him encouragingly, and work on.

Suddenly the little fellow gave a cry of terror and slid from the porch, trailing the shawl after him, his crutch jerking over the ground, his sobs almost choking him.

“Mammy! Cully! Stumpy's tied in the loft! Oh, somebody help me! He's in the loft! Oh, please, please!”

In the roar of the flames nobody heard him. The noise of axes beating down the burning fences drowned all other sounds. At this moment Tom was standing on a cart, passing up the buckets to Carl. Cully had crawled to the ridge-pole of the tool-house to watch both sides of the threatened roof.

The little cripple made his way slowly into the crowd nearest the sheltered side of the tool-house, pulling at the men's coats, pleading with them to save his goat, his Stumpy.

On this side was a door opening into a room where the chains were kept. From it rose a short flight of six or seven steps leading to the loft. This loft had two big doors—one closed, nearest the fire, and the other wide open, fronting the house. When the roof of the burning stable fell, the wisps of straw in the cracks of the closed door burst into flame.

Within three feet of this blazing mass, shivering with fear, tugging at his rope, his eyes bursting from his head, stood Stumpy, his piteous bleatings unheard in the surrounding roar. A child's head appeared above the floor, followed by a cry of joy as the boy flung himself upon the straining rope. The next instant a half-frenzied goat sprang through the open door and landed in the yard below in the midst of the startled men and women.

Tom was on the cart when she saw this streak of light flash out of the darkness of the loft door and disappear. Her eyes instinctively turned to look at Patsy in his place on the porch. Then a cry of horror burst from the crowd, silenced instantly as a piercing shriek filled the air.

“My God! It's me Patsy!”

He carried the almost lifeless boy

Tom hurled herself into the crowd, knocking the men out of her way, and ran towards the chain room door. At this instant a man in his shirt-sleeves dropped from the smoking roof, sprang in front of her, and caught her in his arms.

“No, not you go; Carl go!” he said in a firm voice, holding her fast.

Before she could speak he snatched a handkerchief from a woman's neck, plunged it into the water of the horse-trough, bound it about his head, dashed up the short flight of steps, and crawled toward the terror-stricken child. There was a quick clutch, a bound back, and the smoke rolled over them, shutting man and child from view.

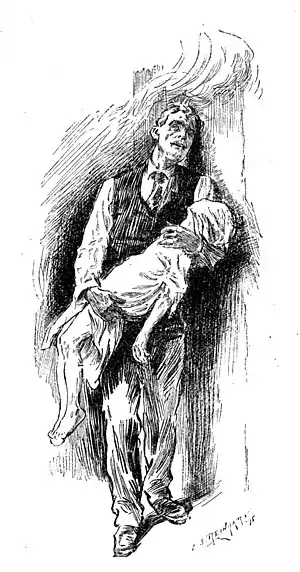

The crowd held their breath as it waited. A man with his hair singed and his shirt on fire staggered from the side door. In his arms he carried the almost lifeless boy, his face covered by the handkerchief.

A woman rushed up, caught the boy in her arms, and sank on her knees. The man reeled and fell.

·······

When Carl regained consciousness, Jennie was bending over him, chafing his hands and bathing his face. Patsy was on the sofa, wrapped in Jennie's shawl. Pop was fanning him. Carl's wet handkerchief, the old man said, had kept the boy from suffocating.

The crowd had begun to disperse. The neighbors and strangers had gone their several ways. The tenement-house mob were on the road to their beds. Many friends had stopped to sympathize, and even the bitterest of Tom's enemies said they were glad it was no worse.

When the last of them had left the yard, Tom, tired out with anxiety and hard work, threw herself down on the porch. The morning was already breaking, the gray streaks of dawn brightening the east. From her seat she could hear through the open door the soothing tones of Jennie's voice as she talked to her lover, and the hoarse whispers of Carl in reply. He had recovered his breath again, and was but little worse for his scorching, except in his speech. Jennie was in the kitchen making some coffee for the exhausted workers, and he was helping her.

Tom realized fully all that had happened. She knew who had saved Patsy's life. She remembered how he laid her boy in her arms, and she still saw the deathly pallor in his face as he staggered and fell. What had he not done for her and her household since he entered her service? If he loved Jennie, and she him, was it his fault? Why did she rebel, and refuse this man a place in her home? Then she thought of her own Tom no longer with her, and of her fight alone and without him. What would he have thought of it? How would he have advised her to act? He had always hoped such great things for Jennie. Would he now be willing to give her to this stranger? If she could only talk to her Tom about it all!

As she sat, her head in her hand, the smoking stable, the eager wild-eyed crowd, the dead horses, faded away and became to her as a dream. She heard nothing but the voice of Jennie and her lover, saw only the white face of her boy. A sickening sense of utter loneliness swept over her. She rose and moved away.

During all this time Cully was watching the dying embers, and when all danger was over,—only the small stable with its two horses had been destroyed,—he led the Big Gray back to the pump, washed his head, sponging his eyes and mouth, and housed him in the big stable. Then he vanished.

Immediately on leaving the Big Gray, Cully had dodged behind the stable, run rapidly up the hill, keeping close to the fence, and had come out behind a group of scattering spectators. There he began a series of complicated manœuvres, mostly on his toes, lifting his head over those of the crowd, and ending in a sudden dart forward and as sudden a halt, within a few inches of young Billy McGaw's coat-collar.

Billy turned pale, but held his ground. He felt sure Cully would not dare attack him with so many others about. Then, again, the glow of the smouldering cinders had a fascination for him that held him to the spot.

Cully also seemed spellbound. The only view of the smoking ruins that satisfied him seemed to be the one he caught over young McGaw's shoulder. He moved closer and closer, sniffing about cautiously, as a dog would on a trail. Indeed, the closer he got to Billy's coat the more absorbed he seemed to be in the view beyond.

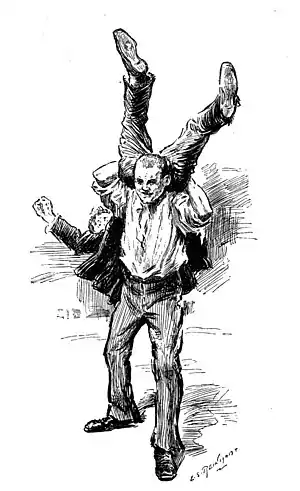

Here an extraordinary thing happened. There was a dipping of Cully's head between Billy's legs, a raising of both arms, grabbing Billy around the waist, and in a flash the hope of the house of McGaw was swept off his feet, Cully beneath him, and in full run toward Tom's house. The bystanders laughed; they thought it only a boyish trick. Billy kicked and struggled, but Cully held on. When they were clear of the crowd, Cully shook him to the ground and grabbed him by the coat-collar.

“Say, young feller, where wuz ye when de fire started?”

At this Billy broke into a howl, and one of the crowd, some distance off, looked up. Cully clapped his hand over his mouth. “None o' that, or I'll mash yer mug—see?” standing over him with clenched fist.

“I warn't nowheres,” stammered Billy. “Say, take yer hands off'n me—ye ain't”—

“T'ell I ain't! Ye answer me straight—see?—or I'll punch yer face in,” tightening his grasp. “What wuz ye a-doin' when de circus come out—an', anoder t'ing, what's dis cologne yer got on yer coat? Maybe next time ye climb a fence ye'll keep from spillin' it, see? Oh, I'm onter ye. Ye set de stable afire. Dat's what's de matter.”

“I hope I may die—I wuz a-carryin' de can er ker'sene home, an' when de roof fell in I wuz up on de fence so I c'u'd see de fire, an' de can slipped”—

“What fence?” said Cully, shaking him as a terrier would a rat.

“Why dat fence on de hill.”

That was enough for Cully. He had his man. The lie had betrayed him. Without a word he jerked the cowardly boy from the ground, and marched him straight into the kitchen:—

“Say, Carl, I got de fire-bug. Ye kin smell der ker'sene on his clo'es.”

Billy kicked and struggled, but Cully held on