CHAPTER II

The Sign of the Three

OUT of doors, high noon, spring, the clamorous life of New York swift running through its brilliant streets.

Within doors, neither sound nor sunbeam disturbed a perennial quiet that was yet not peace.

The room was like a well of night, the haunt of shadows and sinister silences. Heavy hangings darkened its windows and masked its doors, a carpet of velvet muffled its floor, bookcases lined its walls. From the topmost shelves pale sculptured masks peered down, incarnadined by the dim glow from a solitary light that burned in that darkness like a smouldering ember.

The electric bulb of ruby glass was focussed upon a leather-bound desk-blotter on a black desk whose farther edges blended with the shadows.

Little was visible beyond the radius of that light and the figure of an old man that brooded over it, motionless in a great leather-bound chair.

His hair was as white as his heart was black; his nose was aquiline, finely chiselled, his cheek-bones high and sharp. His mouth resembled a steel trap; while his forehead shelved back sharply from ragged black brows that shadowed eyes like live coals.

He was clothed in a black dressing-gown, and from the thighs down was covered by a woollen rug. He stared unblinking at the crimson blotter: a man seven eighths dead, completely paralyzed but for his head and his left arm.

A figure of savage patience he sat waiting—for years on end, for so long that those who knew him had well-nigh forgotten that Seneca Trine once had been as vital a creature as ever lived.

Presently a faint clicking disturbed the stillness. Seneca Trine had put forth his left hand and touched a button embedded in the desk. Something else clicked—this time a latch. There was the faint sound of a closing door, the hangings rustled, and a smallish man in black stole into the light, paused beside the desk, and waited for leave to speak.

The voice of Trine rang like a bell in the silence, a weirdly deep and sonorous voice to issue from that wasted frame.

"Well?"

"A telegram, sir—from England."

"Give it me!"

The old man seized the sheet of yellow paper, scanned it hungrily, and crushed it with a gesture of uncontrollable emotion. His voice rang with exultation when next he spoke:

"Send my daughter Judith here!"

The servant disappeared, and two minutes later a young woman in street dress was admitted to the chamber of the shadows. She went directly to her father, bent over and touched her lips to his forehead.

He did not speak, but her quick ears caught the rustle of the paper crushed anew in his grasp, and she experienced an intuition of something momentous impending.

"You sent for me, father?"

He replied brusquely: "Sit down."

She found a chair and settled herself in it.

"Now turn the light upon your face."

The red glow lighted up a face of exquisite beauty, an eager, passionate face mirroring the spirit of quenchless youth, and her father nodded slightly as if with satisfaction.

"Judith—tell me—what day is this?"

"My birthday. I am twenty-one."

"And your sister's birthday? Rose, too, is twenty-one."

A slight frown clouded Judith's face; but she replied quietly: "Yes."

"You could have forgotten that," the old man pursued almost mockingly. "Do you dislike your twin-sister so intensely?"

The girl's voice trembled. "You know," she said, "I hate and despise her."

"Why?"

"We have nothing in common—beyond parentage and this abominable resemblance. Our natures differ as light from darkness."

"And which would you say was—light?"

"Hardly my own: I'm no hypocrite. Rose is everything that they tell me my mother was, while I"—the girl smiled strangely—"I think—I am more your daughter than my mother's."

A nod of the white head confirmed the suggestion. "It is true. I have watched you closely, Judith. Before I was brought to this"—the wasted hand made a significant gesture—"I was a man of strong passions. … Your mother never loved, but rather feared, me. And Rose is the mirror of her mother's nature: gentle, unselfish, sympathetic. But you, Judith, you are like a second self to me."

An accent of satisfaction was in his voice. The girl waited, tensely expectant.

"Then, if I were to ask a service of you that might injuriously affect the happiness of your sister"

The girl laughed briefly: "Only ask it!"

"And how far would you go to do my will"

"Where would you stop in the service of one you loved?"

Seneca Trine permitted himself an odd mirthless

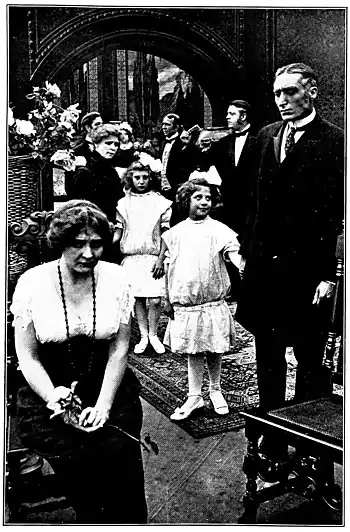

TRINE SUSPECTED HIS WIFE. OF WHAT, HE COULD NOT TELL.

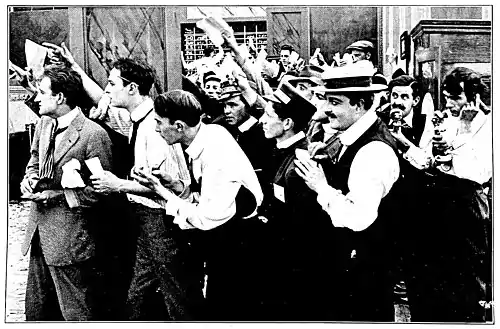

ON THIS DAY, LAW, SR., WENT DOWN TO FINANCIAL DEFEAT

The girl half-started from her chair, but with visible effort controlled herself.

"Oh, I know—I know!" the father continued. "I am a prisoner of this living tomb; but all things I should know—somehow—in time—I come to know."

"It's true—that Englishman last year—what's his name?—Law, Alan Law."

"In the main," the father corrected, "you are right. Only he's not English. His father was Wellington Law, the banker."

She knew better than to interrupt, but her seeming patience was belied by the whitening knuckles of a hand that lay within the little pool of blood-red light.

Presently the deep voice rolled on: "Law and I were once friends; then—we loved one woman, your mother. I won her—all but her heart: too late she realized it was Law she loved. He never forgave me, nor I him. Though he married another woman, still he held from me the love of my wife. I could not sleep for hating him—and he was no better off. Each sought the other's ruin; it came to be an open duel between us in Wall Street. One of us had to fail—and I held the stronger hand. The night before the day that was to have seen my triumph I walked in Central Park, as was my habit, to tire my body so that my brain might sleep. I was struck by a motor-car, picked up insensible—and lived only to be what I am. Law triumphed in the Street while I lay helpless; only a remnant of my fortune remained to me. Then his chauffeur, discharged, came to me and sold me the truth; it was Law's car with Law at the wheel that had struck me down—a deliberate attempt at assassination. I sent Law word that I meant to have a life for a life. For what was I better than dead? I promised him that, should he escape, I would have the life of his son. He knew I meant it, and sent his wife and son abroad. Then he died suddenly—I believe from fear of me."

Trine smiled. "I had made his life a reign of terror. Ever so often I would send him—mysteriously always—a Trey of Hearts: it was my death-sign for him. Every time he received a Trey of Hearts, within twenty-four hours an attempt of some sort would be made upon his life. The strain broke down his nerve. …

"Then I turned my attention to the son, but the Law millions mocked my efforts; their alliance with the Rothschilds placed mother and son under the protection of every secret police in Europe, but they dared not come home. At length I realized that I must wait game. I needed three things: more money; to bring Alan Law back to America; and an incorruptible agent. I ceased to persecute mother and son, and by careful speculations repaired my fortunes. In Rose I had the lure to draw the boy back to America; in you, the one person I could trust.

"I sent Rose abroad under an assumed surname and arranged that she should meet Law. They fell in love at sight. Then I wrote her that the man she had chosen was the son of him who had murdered all of me but my brain. It fell out as I foresaw: she broke off with Law without telling him the truth. You can imagine the scene—passionate renunciation—pledges of constancy—the arrangement of a secret code whereby, when she needed him, she would send him a single rose—the birth of a great romance!"

The old man laughed sardonically. "Well … the rose has been sent; Law is already homeward bound; my agents are watching his every step. The rest is in your hands."

The girl bent forward, her eyes aflame in a pallid face.

"What is it you want of me?" she asked in a vibrant voice.

"Bring Alan Law to me. Dead or alive, bring him to me. But alive, if you can compass it: I wish to see him die."

The hand of youth grasped the icy hand of death-in-life.

"I will bring him," Judith swore. "Dead or alive, you shall have him here."