Chapter IX.

FROM LEOPOLD TO MODERN TIMES.

In the year 1654 the oldest son of the emperor, who had been crowned King of Bohemia as Ferdinand, died; and the second son, Leopold, was declared the heir. The following year Ferdinand III died, and Leopold ascended the throne as Emperor of Austria and King of Bohemia.

Although this ruler enjoyed a long and prosperous reign, his government had little bearing upon affairs in Bohemia, all remaining about the same as in the reign of his father.

One of the most noteworthy events was the uprising of the peasants, who were driven to this desperate step by the frightful tyranny of their masters. This rebellion ended as all such rebellions did—they were overcome by superior forces, the leaders tortured and hanged, and the unfortunate peasants compelled to return to their homes and again endure the cruelty of their oppressors. There was, however, a little variation in this rebellion; many peasants fled to the mountains, preferring starvation to the previous life-in-death that they had endured; and as the lords could not perform the needed labors, they resorted to peaceable measures to induce some of them to return. Some concessions were also granted by the government; but these were little heeded, and the condition of the people was soon as hard as before.

During the peasant war the fields, as a matter of course, were neglected, which brought on a famine the following year (1681). The number of people dying was about 100,000, Prague alone losing a third of this number.

The year 1682 is notable as the time when the Turks were expelled from Hungary, where for so many years they had held much territory. The successful issue of this war was mostly due to the heroic efforts of John Sobieski, the King of Poland.

During the reign of Leopold commenced the war of the Spanish Succession; but this did not affect Bohemia any further than that she was obliged to furnish her quota of troops and pay heavier taxes.

Leopold died in 1705, after a reign of forty-eight years, and his oldest son Joseph became emperor, as Joseph I.

JOSEPH I.

Joseph was a man endowed with uncommon gifts of mind; and no sooner had he assumed the government than he began to prepare to introduce into the country many needed reforms. He appointed various committees to investigate the condition of the different departments of the government, and to make such suggestions as they deemed necessary for their improvement.

The war of the Spanish Succession going on, and Joseph, wishing to be better able to aid his brother Charles, sought by various methods to win the favor of the German princes. Among the concessions granted them was one bearing directly upon Bohemia. This kingdom, like the German States, was to furnish its part of taxation for the support of the Imperial government, in consideration of which it was entitled to claim its protection in time of war. This privilege was granted to the Imperial government, with the express understanding that the integrity of the Bohemian crown, together with its ancient privileges, was to remain intact.

Before Joseph could carry into effect any of his reforms he died (1711), and his brother Charles became the ruler. As King of Bohemia, he is known in history as Charles II, but as Emperor of Germany as Charles VI.

The unexpected death of Joseph I gave a new turn to the Spanish war; for the European princes, seeing that, by the death of Joseph, Charles would become ruler both of Spain and Austria, objected to the formation of so strong a power as dangerous to the peace of Europe. They therefore deserted his cause, compelling him thus to make peace by acknowledging Philip of Anjou as King of Spain, and himself to be contented with the island of Sardinia, the Netherlands, and some minor provinces. The peace was concluded by the Treaty of Utrecht, 1713.

In 1723, Charles came to Prague, and was crowned with great splendor as King of Bohemia. As ruler of that country he paid little attention to the internal affairs of the kingdom, being chiefly concerned with outside politics, meeting, however, little success in that direction. His able general, Eugene of Savoy, did win some lands from the Turks, but at his death they again reverted to their original owners. Charles also lost Naples and Sicily, which he had but recently taken from the Spaniards.

Charles was the last male descendant of the house of Hapsburg, and being anxious to retain the crown in his family, he had a law passed whereby the women of that house were declared the rightful heirs. This law is known in history as the Pragmatic Sanction, and it was solemnly agreed to by all the princes composing the empire, as well as by other European powers. By this law, Charles’s eldest daughter, Maria Theresa, became his immediate heir. In 1736 she was married to Francis Stephen, the Duke of Tuscany, of the house of Lorraine. In 1740, Charles died, and Maria Theresa became Empress of Austria.

MARIA THERESA.

Although the right of inheritance to the Austrian dominions had been confirmed to Maria Theresa by so many solemn promises and agreements, no sooner was her father dead than numerous princes rose up as claimants, either to parts or to the whole of her provinces. Among these were the Electors of Bavaria and Saxony, and the Kings of Spain, Sardinia, and Prussia. All based their claims upon the rights of relationship, or upon the false interpretation of documents long forgotten.

The most dangerous of these claimants was Frederick of Prussia, who began to make immediate preparations to seize a part of Silesia. As Maria Theresa was not prepared for war, Frederick soon gained possession of the whole of that province, and then turned his victorious arms against Bohemia, the Saxons and Bavarians invading it from another direction. Prague was soon in the hands of the enemy.

Charles, the Elector of Bavaria, had himself proclaimed King of Bohemia. Calling together the lords and knights to the number of 400, whose estates were mostly in his power, he compelled them to take the oath of allegiance, which was done with great solemnity in the cathedral at Hradschin. The chief officers of the State, not wishing to violate their oath of allegiance to the queen, had left the city. Charles appointed other officers to take their places; then called a Diet, which granted him a heavy subsidy. He then took his departure for Frankfort, where he was chosen by the electors Emperor of Germany (1742).

Meanwhile the Hungarians had espoused the cause of Maria Theresa, calling her their “king,” and raised a large army to go to her assistance. The English and the Russians also lending their aid, her condition began to assume a more hopeful aspect. In order to be rid of her most formidable rival, she ceded the whole of Silesia to Frederick, and also the county of Kladrau, which had always been an integral part of Bohemia. The Elector of Saxony also joining in this peace, the queen was now free to turn her whole strength against the French and the Bavarians.

The allies under the command of Marshal Belleisle, to the number of 30,000, invaded Bohemia and shut themselves up in Prague, where they were besieged by Charles of Lorraine, the queen’s brother-in-law.

The French defended themselves bravely for eleven weeks, at the close of which they were reduced to such want that they ate horseflesh. While in this extremity, a large army of their countrymen were coming to their assistance; but they were prevented from crossing the boundaries by Charles, who raised the siege to go to meet the new enemy. The opportunity was embraced by the French army to leave the city, which was done in December during a season of very cold weather, and the troops being destitute of both proper clothing and provisions, many of them perished before they reached Eger, the first halting place.

Bohemia was thus delivered from the enemy, and the government of Charles of Bavaria came to an end. In the spring of 1743, Maria Theresa came to Prague, and was solemnly crowned Queen of Bohemia. The ceremony was performed by the Bishop of Olmutz, the Archbishop of Prague being in disfavor on account of his adherence to Charles of Bavaria. Many of the lords who had sworn allegiance to the usurper had also much to fear. But Maria Theresa, unlike her ancestor Ferdinand, finally granted pardon to all, so that not a single execution marred the beginning of her prosperous reign. She remained in Prague six weeks, and then returned to Vienna, carrying with her the Bohemian crown, which remained there until the time of Leopold II.

In the meantime the queen’s army carried on so successful a war against the Emperor Charles VII as to deprive him of the whole of Bavaria. Put to these straits, he appealed for aid to Frederick of Prussia, who broke the peace he had made with Maria Theresa, and again invaded Bohemia. Again he obtained possession of Prague; but he did not hold it long, being soon driven away by Charles of Lorraine.

Some time after the above events Charles VII died, and his son Maximilian, desirous of regaining his hereditary provinces, made peace with the empress, renouncing all claims to her territories.

The vacancy caused by the death of Charles VII was filled by the election of Francis, the husband of Maria Theresa, as Emperor of Germany. Frederick of Prussia also acknowledged his authority, and a peace was made at Dresden in 1745.

From the year 1745 to 1756 the land had peace, so that it was enabled, to some extent, to recuperate the strength wasted in so many wars; but in 1756 another war broke out, which is known in history as the Seven Years’ War.

THE SEVEN YEARS’ WAR.

Maria Theresa never became fully reconciled to the loss of beautiful Silesia, and was only waiting for a favorable opportunity to try to regain it. Such a moment seemed to have arrived in the year 1756, when, having gained France as an ally, she declared war against Frederick.

At the very beginning of the war, Frederick invaded Bohemia, and, after gaining a brilliant victory at Lovosic, he marched to Prague, where Charles of Lorraine was waiting to receive him. A battle was fought, where Frederick gained another victory, compelling Charles to shut himself up in Prague, where he was besieged by the Prussians for six weeks. The enemy, trying to force him to surrender, kept up a constant bombardment upon the city, sadly damaging some of the finest buildings, among these the cathedral on the Hradschin. Finally, the Field Marshal Daun coming to the assistance of the distressed city, Frederick raised the siege, and went to meet the coming army. A decisive action took place at Kolin. Frederick was defeated, and compelled to leave the country in the wildest disorder, having lost 20,000 men.

From that time on, the war was carried on outside of Bohemia, mostly in the dominions of Frederick. The two generals, Daun and Laudon, inflicted many crushing blows upon the Prussian army, which certainly would have discouraged any ruler not possessed of so indomitable a spirit as Frederick.

Joseph II. As soon as his army sustained a defeat in one place, he hastened to make it up by a victory elsewhere, so that, notwithstanding the glorious successes of the Imperial army, the advantage did not seem to lean either to the one side or the other.

Finally, both the sovereigns becoming weary of the war, to prevent further devastation of territory and bloodshed, a peace was made in 1763, leaving affairs as they were before the war.

In 1764, Joseph, the oldest son of Maria Theresa, was elected King of the Romans, and his father dying the following year, he became Emperor of Germany, being made also joint-ruler with the queen of the Austrian dominions.

Like his ancestor of the same name, Joseph was a man possessed of uncommon gifts of mind and heart; and having, through study and travel, gained much knowledge and experience, he early began to form plans for working a great reform in his dominions. As his plans were very radical and far-reaching in their consequences, he dared not make them fully known while his mother still lived, but contented himself with carrying out the more zealously the reforms that she herself had proposed.

The rulers that governed the country the years following the Thirty Years’ War concerned themselves far more with external politics than with the internal affairs of their own State.Changes during the Reign of Maria Theresa and Joseph II. This was partly due to the old State system, which proved inadequate to the new conditions, and partly to their own indifference. It will be remembered that Joseph I had appointed several committees to study what changes were needed in the various departments, but died before anything could be accomplished, and his brother Charles failed to appreciate the importance of the needed reforms. His daughter, Maria Theresa, however, was gifted with a far more progressive mind, and early reached the conclusion that, if her subjects were to be prosperous and happy, far more attention must be paid to the internal affairs of the State. Even in the midst of wars she renewed the old committees, and infused new life into them; and very soon the good results of their work began to manifest themselves. The administration of law was greatly improved, and many ancient abuses were removed.

One of the changes, which proved a great blessing to the country, was the establishment of courts having jurisdiction in cases of capital punishment. In Bohehemia alone there were three hundred and seventy-eight towns where criminal courts were held. These were now reduced to twenty-four, and placed in the hands of competent judges, men well versed in the laws. From that time on, no one had to fear that he would lose his life through the maliciousness of some lord or official.

Another important reform introduced was a change in the school system. Up to this time the schools had been in the hands of Jesuits, whose educational methods tended rather to benumb than enlighten the understanding. Maria Theresa deprived the Jesuits of their control of public education, placing it in the hands of a commission of learned men, who had authority over all the schools in her dominions. Many new professorships were established in the university, and rapid progress was made in the arts and sciences.

The government of Maria Theresa, although beneficent in its designs, was not without its evils, like all absolute monarchies. Bohemia was deprived of the last vestige of self-government. In the old days the country was divided into circuits, the officers in these being appointed by the States; but under her government they were appointed by the crown, and responsible for their actions only to the chief officers in Vienna. Indeed, the whole government became a vast system of bureaucracy, having its center in Vienna. This was the case in Bohemia and in some of the other Austrian provinces, but not in Hungary. The empress favored that country, partly from gratitude and partly from fear. The latter motive has, doubtless, governed the actions of Austrian monarchs ever since; for Hungary has always enjoyed more liberty and home-rule than any other Austrian province.

Whatever was done thus far, was done under the auspices of Maria Theresa alone; but when, in 1764, Joseph was made joint-ruler, the work of reform began to be pushed forward with far more speed and energy.

One of the chief aims that Joseph II set before himself was to improve the material condition of his subjects, by removing the evils under which they suffered and lightening their tasks and burdens. He showed his benevolent spirit in the years 1770 and 1771, called the “Hungry Years,” when there was great want in the land on account of a poor harvest. There was such a scarcity of food that many of the people ate grass and the leaves of trees, in consequence of which various diseases appeared among them, causing a great mortality. When the news of this reached Vienna, Joseph himself hastened to Bohemia, opened the military magazines, sent to Hungary for rye and rice, and had the provisions freely distributed among the suffering people.

Joseph II was a zealous adherent of the French Encyclopedists; therefore he hailed with joy the news that the Order of Jesuits had been abolished by the Pope.Further Reform in Education They were now deprived of their colleges and schools; their property was taken away and formed into a fund devoted to the needs of secular education; their books, collected from numerous monasteries, were placed in the library of the university. The theological and philosophical professorships were placed into the hands of professors of other orders, and also among those not belonging to any religious order.

A new school system was also organized for the gymnasiums and the primary and intermediate schools, which up to this time had been entirely in the hands of the parish priests.

The new school system, although excellent in regard to better methods of instruction, did not prove such a blessing to the Bohemian people, which was due to the fact that German was made compulsory in all the schools.

Joseph II cherished the plan of consolidating the various peoples inhabiting his dominions into one great nation having one common language, Joseph’s Centralization Plans.that language being the German. This grand plan was to be carried into effect through the medium of schools and public offices. As the country people still clung to their mother tongue, this was a source of great hardship to them; for while a German youth entering the gymnasium had everything taught him in his own language, the Bohemian one was compelled first to master a language foreign to him, and which he often regarded with hatred. The introduction of German into public offices was a source of still greater trouble. All the official papers and legal documents were ordered to be written in German, which the peasants could not understand, and which the haughty officials, creatures of the government, would not deign to explain. As the official was responsible only to Vienna, there was no method of redress, and thus the people were forced to endure innumerable hardships and persecutions.

But as every species of oppression carried to excess reacts upon itself, bringing its own punishment, so this cruel persecution of the Bohemian people proved the very means of rousing the national spirit, and awakening an interest in the cultivation of a language neglected for so many generations.

Men of letters, in whom the national consciousness had not died out, now began to work to awaken the same feelings in others, and in due time the fruits of their labors began to appear. Thus it was that the period of the greatest humiliation of the Bohemian language, proved to be the dawn of a new era, in which the nation may yet regain much of its former liberty and importance.

The government introduced many reforms, and was sincere in its attempts to alleviate the condition of the people,The Socage Patent and Peasant Uprising. but the relationship of the peasants to their lords was such as to permit the most grievous oppression. Driven to desperation, the peasants arose in rebellion, seeking redress at the court in Vienna. The matter was laid before Diets called for this purpose both in Bohemia and Moravia. The States refused to pass any law reducing the number of days’ tasks required from the peasants, but gave the queen to understand that they would acquiesce in any change that was made by the central government. Thereupon, a patent was issued that did away with many abuses and reduced the tasks to about one half.

When this patent was read to the people, they refused to believe that it was the true one, a report having been spread that the lords had denied the genuine document, and shown the people a counterfeit one.

The peasants again rose in rebellion. Several thousand of them marched to Prague with the determination to get possession of the true patent. On their way they committed many acts of violence, such as breaking into the castles of the lords and inflicting all manner of indignities upon the officials, who, on account of their cruelties to the peasants, were always the objects of their special hatred.

Before they reached the city, they were met by an armed force and soon scattered, some of them being taken prisoners. To strike terror into the hearts of the wretched people and prevent any further outbreaks, four of the leaders were condemned to death, and hanged, one on each of the principal highways leading to Prague. There were skirmishes in several other places between the peasants and the troops; but these did not lead to any serious results. After that. General Oliver Wallis traveled through the country, announcing with great ceremony the contents of the true patent; and the people, learning that such was the will of the government, became quiet, thankful to have their burdens lightened, even though it were but partially.

Another reform introduced by Maria Theresa was the abolition of all torture in cases on trial, and also all cruel and unnatural methods of execution;Torture abolished. such as breaking on the wheel, flaying, and the like. Trials of witches, as well as all laws against witchcraft, were also done away with.

In 1780, after a successful reign of forty years, Maria Theresa died, being sincerely mourned by all her subjects.

JOSEPH II.

Perhaps there never was another ruler who, in so short a time, introduced so many changes in both the public and private life of his subjects as the Emperor Joseph II. While he was joint-ruler with his mother, his infatuation for reforms and innovations was kept within the bounds of reason; but as soon as she was gone, he laid aside all reserve, and plunged with headlong impetuosity into the work of transforming his countries into such a state as he deemed would best insure the prosperity of his subjects. In his blind zeal for reform he did not take into consideration the long-established customs of the people, their habits of life, and mode of thought; indeed, he ignored all the ancient rights and privileges, not deeming it beneath his dignity to meddle in the most petty affairs of private life.

The year after the death of his mother, Joseph II issued the Toleration Patent, which may be regarded as one of the most benevolent and progressive acts of his reign.The Toleration Patent By this patent, people non-Catholic obtained the privilege of openly professing their faith, and of building churches and schoolhouses. Notwithstanding all the labors of the Jesuits and other Catholics, there were still many people in the land who in secret held to the Protestant faith. Even as late as 1731, some of these familes, being discovered and fearing persecution, left the country, forming settlements near Berlin and in Silesia, which did not then belong to the Austrian dominions. When the Toleration Patent was announced, some 100,000 persons appeared before the proper authorities to have themselves matriculated as Protestants. These people were generally called Hussites, but they were the remnants of the Bohemian Brethren. The government, knowing nothing about this sect, required them to adopt either the Augsburg or the Calvinistic Confession of Faith, which most of them willingly did. Still there were quite a number among those claiming the privilege of the Patent that refused to join either sect, calling themselves Adamites. The history of those times charges them with gross errors in faith and many wicked practices. Even if these charges be true, the methods that they were dealt with sadly belie the vaunted liberalism of Joseph II. The adults were transported to Hungary and Transylvania, and their children placed in Catholic families to be brought up. A law was also passed that any one publicly professing to be a Deist—thus the authorities called this sect—should receive twelve blows with a club.

The number of Protestants rapidly increased, so that, even during the reign of Joseph II, there were forty-eight churches, having a membership of 45,000 souls; thirty-six of these were of the Calvinistic, and twelve of the Augsburg Confession. Each of these sects was granted a superintendent, who was directly responsible to the crown.

As the Protestant Churches were thus placed directly under the control of the government, so Joseph determined that the Church in general should be subordinate to the State. To this end, he ordered that no Papal bull should be announced in any of his dominions, unless it had first been submitted for approval to the civil authorities. Henceforth monasteries were not to be subject to any power non-resident in the dominions of Austria. Later, Joseph ordered the abolition of all convents that he deemed unnecessary, leaving only those that devoted themselves to the education of youth or to the care of the sick. From 1782 to 1788, fifty-eight of these institutions were either destroyed or devoted to other purposes. The property was confiscated to the State, and was set aside as a fund for the support of Churches. This made it possible for many new churches to be built in towns and villages that had been without any means of religious instruction, the inhabitants being obliged to go to service a great distance from their homes.

The Pope, then Pius VI, looked on in consternation at all these unheard-of innovations; and when remonstrances proved unavailing, his Holiness did an act unprecedented in history—he himself undertook a journey to Vienna to try to dissuade the emperor from making any further encroachments into the ecclesiastical domains. But although he was received and entertained with great honor, he failed of accomplishing his purpose.

The emperor went on in his Church reform by taking away a part of the diocese of the Archbishop of Prague and attaching it to the bishoprics, thus equalizing somewhat the income and the jurisdiction of these prelates. Their power, on the other hand, was much limited by removing marriage from their jurisdiction, placing it under the control of the civil authorities.

While these innovations were introduced, the Pope was silent; but when Joseph went so far as to prohibit pilgrimages to the various shrines in the country, and to dictate as to what sort of ceremonial should be observed in Church service, his Holiness again raised his voice in protest, this time threatening to use the extreme penalties of the Church against the daring monarch if he heeded not the warning of the Church. Joseph, not wishing to bring down upon himself the wrath of all the priesthood, left well-enough alone, and the Pope also was content with this partial obedience.

Another good work that this progressive ruler did, was to take the censorship of the press from the control of the clergy, and place it in the hands of enlightened laymen. He also did much to encourage science. In 1769 a society had been organized in Bohemia for the cultivation of science. Joseph elevated this private organization into a State society, entitled “The Scientific Society of the Kingdom of Bohemia.” This gave a great impetus to the cultivation of science, especially to the mathematical and physical sciences, and also to historical researches.

One of the greatest blessings granted his subjects by Joseph II, was the abolition of personal servitude. According to the new law, the peasants were free to move from their homesteads, to send their sons to learn any trade they wished, without asking the consent of their lords; their estates became allodial, socage was considerably reduced, and the sum fixed by which a peasant could obtain exemption from such duty.

As far as courts of justice were concerned, the peasants still remained under the jurisdiction of their lords; but these were required to have judges well versed in the laws, and to conduct the trials according to the general laws of the land.

Nowhere did Joseph show greater activity than in the improvement of the judicial departments. One of his chief aims was to secure entire uniformity in the administration of law, this seeming to him the most effective method for carrying out his plans of centralization. One sweeping change after another was made in utter disregard of the customs, rights, and privileges of towns and cities. The new laws introduced were based partly upon the old Roman law, and partly upon the unwritten common law. The change in the laws themselves would have proved a great blessing had not their administration been placed entirely in the hands of State officers, thus depriving the people of all self-government.

The States, composed of the three orders of lords, knights, and citizens, that in the old days had been stich a power when assembled in the Diets, now had their power entirely broken, their duties being transferred to one of the departments of the general government.

Unlike his mother, Joseph did not grant any favors to the Hungarians; and to avoid the promise, usually given in the coronation oath, that he would preserve the liberties of the country, he refused to be crowned either as King of Bohemia or of Hungary.

Mention has already been made of the great injustice done the Bohemians in regard to their language, even during the reign of Maria Theresa. After her death it was worse. Joseph II, anxious to see the work of centralization going on more rapidly, pushed forward the use of the German tongue with more and more unscrupulousness, thus inflicting many hardships upon the poor peasants, who could not master a strange language in so short a time.

Another irremediable wrong done the Bohemian people, was the destruction of many of their ancient works of art. Joseph was a utilitarian to the last degree, and, had it been in his power, he would have destroyed everything that did not in some way contribute to the material prosperity of the nation. Ancient monasteries, beautiful churches filled with paintings and sculpture, were abandoned and suffered to go to decay; and the treasures of art were often sold for the price of old trappings. Indeed, an attempt was made to transform the beautiful palace upon the Hradschin to soldiers’ barracks.

As an offset, however, to this destructive tendency against the nation’s most cherished memorials, may be mentioned his benevolent institutions. In 1783, Joseph established the first orphan asylum; in 1784, a poorhouse; in 1786, an asylum for the deaf and dumb; in 1789, a hospital for unfortunate girls, together with a foundling asylum,—these all being in the city of Prague.

The government of Joseph, although an absolute despotism, was so tempered with benevolence that the people, doubtless, Dissatisfaction with Joseph’s Government.would have submitted to it in patience, had not the infatuated ruler gone a little too far in his paternal meddlesomeness. When Joseph forbade all costly funerals, and ordered that the money of orphans should not be put out at a higher rate of interest than three and one-half per cent, the people began to murmur; but, these murmurs gave place to loud expressions of indignation when he tried to enforce the law whereby illegitimate children shared equally in the property of their parents with those born in lawful wedlock; and surely it was a ridiculous stretch of royal authority to prohibit the sending of cakes among friends on Christmas-tide.

These petty interferences in the private life of his subjects were the immediate cause of much discontent; and when once the fault-finding spirit was aroused, it seemed that no one was satisfied with anything the emperor had done.

This growing dissatisfaction was increased by Joseph’s unfortunate foreign politics. In Germany all his attempts at reform were brought to naught by the opposition of the various princes.

The expression of discontent among individuals was soon followed by that of nations. At first an insurrection broke out in Transylvania, that had to be put down by force of arms. Then the Hungarian nobles arose against their ruler, demanding the convocation of a State Diet. An insurrection broke out in the Netherlands, which, being sustained by Prussia, succeeded in driving the emperor’s troops out of the country. Other disturbances arose also in Bohemia and Tyrol. All this time Joseph put on a bold front, thinking that in due time all would be brought to order; but when the Prussians threatened to join their forces with those of the Turks against him, he perceived the greatness of the danger surrounding him, and immediately began to grant concessions to the people in his provinces. The Hungarians being the most unruly, he began the work of conciliation in that country. Appointing a State Diet to meet in 1789, he promised to have himself crowned the same year. At the same time he repealed some of the most obnoxious laws that had been passed, not only for Hungary, but also for the Netherlands. Tyrol, and Bohemia. These concessions, however, came too late. The Hungarians only mocked at a ruler, who, when sore pressed, showed some lenity, when before that he had been utterly inflexible.

The indomitable spirit of this great ruler was at last broken by disappointment, difficulties, and trials that pressed upon him from all sides; his health, for some time poor, now broke down entirely, and the weary soul took its flight on the 20th of February, 1790 Thus the prince, whose reign had been welcomed with so much rejoicing, now died but little mourned. Greatly beloved at first for his liberality of thought, nobleness of character, and his earnest efforts to improve the condition of his subjects, he at last turned against himself even the hearts of his greatest devotees, when his interference in private affairs was carried beyond the limits of reason.

The peasants, however, whom he had rescued from a cruel servitude, loved him to the last, and for a long time refused to believe in his death.

In regard to personal appearance, Joseph II was a handsome man, of medium height, having a high forehead, and beautiful blue eyes. Although all acknowledged his goodness of heart and praised his simplicity of life, nevertheless, on account of his obstinacy and his domineering ways, he did not succeed in winning the permanent affection of his friends. Still, on account of his sympathy with the poor, his untiring labors to ameliorate their lot, his originality and energy in carrying out his reforms, and his conscientious performance of every duty of state, he is worthy to be regarded as the ablest and best ruler that ever sat upon the throne of the Hapsburgs.

LEOPOLD II.

The successor to Joseph II was his brother, known in history as Leopold II. No sooner had he assumed the government than he announced his intention to renew the old State system; accordingly State Diets were called in all the countries composing his dominions. The delegates drew up their lists of grievances, and also suggestions as to the remedies.

In accordance with his promise, Leopold II repealed many of the decrees issued by his brother, especially those relating to the system of taxation, as well as those laws interfering in Church affairs and in the local affairs of towns and circuits. He partially acquiesced in the demands of the Bohemian Diet asking for the complete abolition of the innovations introduced by Maria Theresa and Joseph II. The Diet was granted the old privilege of voting taxes; but it was still left with the State authorities as to their mode of collection. In regard to their language, the Bohemians succeeded in having a chair of their tongue established in the university; but German still continued to be the language of instruction in the gymnasiums and higher institutions of learning.

In 1791, Leopold II was crowned with great splendor as King of Bohemia. On this occasion the crown was brought from Vienna to Prague, where it afterwards remained. The following year Leopold died, having reigned but two years.

The great evil that Leopold II did, for which he merits the curses of all mankind, was the re-establishment of servitude that his predecessor had with so much difficulty abolished. No words are adequate to express the dismay and despair of the poor peasants when compelled to return to the cruel tasks from which they believed they were forever freed.

FRANCIS I.

Leopold II was succeeded by his son Francis, who was crowned King of Bohemia in 1792.

During the first years of Leopold’s reign, the Bohemian States continued in their efforts to regain their ancient rights and privileges. The French Revolution having broken out some time before, and Austria being involved in the wars that followed, Francis postponed all consideration of the demands of the States until after peace should again be restored.

In 1798, after the Peace of Campo Formio, Count Buquoi brought forward the question whether it was not time for the government to give its attention to this matter; but the suggestion passed unheeded, partly because the war broke out again, but mostly because the government had grown suspicious of all questions touching upon granting any liberties to the people. Indeed, after this time, when any one dared to lift his voice in behalf of liberty, he was at once arrested as trying to disseminate Jacobite heresies. Instead of granting any rights to the Diets, the government began to curtail those they already possessed. In 1800 it imposed a new tax upon the people, without so much as asking the consent of the Diet, the excuse being made that the urgency of the case demanded it. The government also used the new system of making State debts by issuing a paper currency; and when the burden of this debt crippled trade and wrought great confusion in wages and in the sale of property, the Financial Patent was issued (1811), declaring the value of the paper money to be one-fifth of its face. This plunged the country into great misery, many people being reduced to bankruptcy and ruin.

The wars of the allies against France raged on, and although not carried on in Bohemia, they were not without their effects upon that country. In 1806, when the German princes made peace with Napoleon accepting his protection, the old confederation known as the German Empire was dissolved, and Francis I was obliged to lay down the title of German Emperor, and be content with the newly assumed one of Emperor of Austria. The effect of this upon Bohemia was, that it was freed from its ancient duty of furnishing 150 horse whenever the emperor went to Rome to be crowned, and the new duty imposed upon the country by Joseph I of contributing its quota to the imperial treasury, the Kingdom of Bohemia, as a matter of course, ceasing to be an electorate of the empire.

The influence of the French Revolution was felt among all European nations, who, taking courage from France, likewise began to demand more rights from their rulers. While danger threatened them from outside, they made many fair promises, which enabled them to raise troops to support their tottering thrones; but as soon as the danger was removed, these promises were forgotten, and the people groaned under as grievous a despotism as before.

The government of Francis I, in mortal terror lest some of the revolutionary principles should take root in the Austrian dominions, watched with a jealous eye every free movement and liberal expression of thought. The administration of law remained in the hands of the officials appointed by Joseph II, except that their number was from time to time increased until the country endured innumerable evils from the fearful system of bureaucracy thus established. The land was also full of spies, through whose maliciousness many good men were seized and cruelly persecuted.

The government of the country at this time was rather the government of Prince Metternich than of Francis I; for this foreigner was the chief counselor of the emperor, and the despotic policy pursued was due entirely to his influence. The government of Joseph II had indeed been a despotism; but it was an enlightened and paternal despotism, while that of Francis I was blind, selfish, and oppressive in the extreme.

The other evils that afflicted the country during the reign of Metternich were the hard times coming at the close of the French wars; provisions were unusually high, and to this was added the Asiatic cholera that visited the country in 1847.

FERDINAND I.

Francis I died in 1835, and was succeeded by his son Ferdinand, who, as King of Bohemia, was the fifth of that name; but as Emperor of Austria, the first.

Ferdinand as a man was kind-hearted and magnanimous, and the people welcomed him as their sovereign with sincere joy; but owing partly to poor health, and partly to his disinclination to public life, he proved a most weak and inefficient ruler. He retained in his cabinet his father’s counselors, among whom the most objectionable was the hated Prince Metternich. These advisers attempted to continue the old despotic system; but they soon found that it was no longer possible, for the liberty-loving spirit roused in France soon found its way into Western Europe, and, notwithstanding all the efforts of the government to stifle it, made itself heard, filling the hearts of tyrants with alarm.

In Bohemia the awakening of national consciousness was also the direct cause of the awakening of the spirit of liberty. On all sides the people began to study their nation’s history, and with this historical knowledge was awakened a desire to regain at least a part of the lost liberty.

During the reign of Ferdinand V the States tried on several occasions to regain some of their old rights and privileges, but in vain; the king’s counselors being exceedingly loath to relax their grip upon the government. This hopeless struggle continued till 1848, when outside forces compelled the officials to begin a new policy.

MATERIAL AND INTELLECTUAL PROGRESS.

Before going on with the history of the Revolution of 1848, it will be well to take a brief survey of the progress made in Bohemia during the first half of the nineteenth century.

The century previous had been a time of great progress in all European nations. Old prejudices had vanished away, new theories and principles were fearlessly advanced; and on all sides there were indications that a new era had dawned for the human race. One of the peculiar features of the times was the free discussion and investigation of the natural rights of man, which came to be more and more recognized, especially during the reign of Joseph II. In his reign the impetus given to free inquiry was so great that it could not be stifled by the most stringent censorship of the press.

Side by side with the intellectual progress, there was a marked development of the natural resources of the country. The population had increased to 4,000,000 souls; the cultivation of the soil had greatly improved; factories arose on all sides, and many labor-saving machines were introduced. Through private enterprise, great buildings were undertaken, such as iron bridges, railroads, steamboats, and numerous public buildings. Prague increased in size, and so many elegant structures were put up as to render it almost a new city.

To further the progress in arts and science, various societies were organized. Among these was the Technical Institute in Prague, organized in 1802, the first of the kind in the Austrian dominions. In 1833 a society was formed whose aim was to help the smaller artisans by means of lectures, papers, and libraries. A national museum was established in 1893, and soon grew to such proportions as to necessitate the construction of a new building, which, in regard to the beauty of its architecture and its fine location, is one of the chief ornaments of the city of Prague.

As the country advanced in art and science, more and more attention began to be paid to the study of the native language, the foremost scholars of the land devoting to it their time and energies. Among the pioneer workers may be mentioned Pelcel, Procháska, and Kramarius. These were followed by Dobrovský, who investigated and established the laws of Bohemian grammar. Many scholars devoted themselves to composing original poems, or translating the masterpieces of other nations. Among these, the most illustrious was Joseph Jungman, whose excellent translation of “Paradise Lost” was a vindication of the richness and flexibility of the Bohemian tongue. Jungman further did an inestimable service to his country by writing a dictionary, a work so scholarly, so exhaustive, that one can not but marvel how a single individual could ever have accomplished so prodigious a task, even though a lifetime were devoted to the work.

In 1817 the country was thrown into a furor of excitement by the discovery of some ancient specimens of Bohemian literature, known as the Kralodvorský rukopis (Queen’s Court Manuscript).

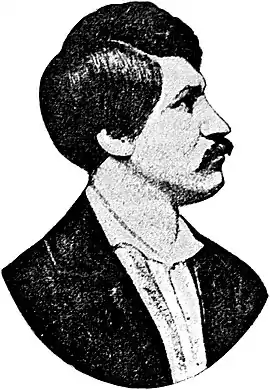

John Kollar,

Author of “Slava’s Daughter.” This was a collection of poems, written on twelve pieces of parchment, and supposed to date back as far as the thirteenth century. Some time after this, another manuscript was discovered at Green Mountain, and hence called Zelenohorský rukopis (Green Mountain Manuscript), the writings of which date back to the ninth century. Although the authenticity of these manuscripts has been hotly contested, they exerted a powerful influence upon the development of the national literature. People began to appreciate a language that, at so early a period, had reached such a high degree of development as to be used in the construction of poems of so much literary merit.

This enthusiasm for the mother tongue doubtless awakened in many a scholar the desire to devote himself to its cultivation. Thus many authors arose, among whom the most distinguished were Kollár, Erben, Jablonský, and Čelakovsky. Kollár’s Slavý dcera (Slava’s Daughter), was the means of awakening much patriotic enthusiasm.

Francis L. Čelakovsky.Jablonský wrote many didactic poems, that were much prized by the common people; Čelakovsky put into verse many ancient tales and folk superstitions; and Erben’s numerous ballads, and collection of folk-songs are invaluable additions to the literature of the country.

Not only in literature, but likewise in science, the Bohemian language began to be used. Presl and Kodym produced a number of works on natural science; Sedlaček, in mathematics; Marek, in philosophy; Palacký and Šafarik, in history. Palacký’s “History of Bohemia” is a work that may stand beside the best histories of other nations; while Šafarik’s “Slavonic Antiquities” is a standard authority in its department.

About this time there was started the paper Casopis Musejni (Museum Journal), which is a grand repository of historical researches. In 1831 there was organized a society called Matice Česka (The Čech Mother), whose object is to publish, at cheap rates, books for the people; following this example, the Catholics organized a similar society called Dedictvi Svatojanske (St. John’s Heritage), their publications being mostly religious books.

Francis Palacky,

Author of “History of Bohemia.” The government, not being able to withstand the pressure brought to bear upon it both by the people and patriotic statesmen, passed a law ordering that Bohemian should be taught in the gymnasiums, and that no one should be admitted to public office not conversant with the native tongue. This law, however, remained mostly a dead letter, for the officials, being creatures of the government, who knew full well what was desired, saw to it that the German language should remain in use, both in schools and public offices.

The national awakening, like all aggressive movements, was not without its accompanying evils; the greatest of which was the unnatural hatred arising between the two nationalities. The Germans, for long years accustomed to regard Bohemia as a German province, and possessing an old-time antipathy to every thing Slavonic, looked with disfavor upon all attempts to resuscitate the Cech tongue. Indeed, in proportion as the zeal of the patriots increased, in that proportion the animosity of the Germans grew, until they became so reckless that they scrupled not to resort to the most malicious and dishonorable means to thwart the plans of their Bohemian neighbors. Some of them took the attitude that the country had always been a German State, and that the actions of the handful of Čechs was as if a party of invaders should enter the country, and try to force upon the natives their own peculiar customs and language.

Notwithstanding all the opposition encountered, both from the government and from private individuals, the good work went on; and as the patriots were the most cultured people of the land, the national awakening proved a source of intellectual advancement to all. There is no question that the marvelous progress that Bohemian literature is making at the present time is but the natural result of this movement.

THE REVOLUTION OF ’48.

In the chapter on the reign of King Ferdinand V, or Ferdinand I of Austria, it was related how the States tried to win back some of their ancient liberties, but without success. In 1848 an event happened outside of the Austrian dominions that had a mighty influence, not only upon that country, but upon all Europe. This was the Revolution in France. The crafty Louis Philippe, refusing to introduce the reforms that the people demanded, was driven from his throne, and the country declared a republic. The news of this Revolution spreading through the countries of Europe, created a great excitement. The people everywhere began to take heart, and to believe that the day of liberty had dawned for all nations. The various rulers, sore pressed,

Ferdinand V (The Good).now granted their subjects many privileges, that nothing could force them to do before.

This example was not lost upon the people of Bohemia, who now saw an opportunity to make known their grievances, and seek redress with a reasonable hope of obtaining it. Some of the States met in Prague, and passed resolutions, asking for the calling of a State Diet, which should propose bills for the needed reforms.

Before the above resolutions could be acted upon, some of the more courageous patriots sought another method of securing the desired end, which, indeed, was not according to law, but, on account of the urgency of the case, met with general approbation. They issued a proclamation to the people, asking them to meet in the hall of the St. Václav’s baths on the 11th of March, to consider the question of drawing up a petition to the emperor. Such a meeting was held on the appointed day, and resolutions embodying the following principles were drawn up:

(1) Equality of the two nationalities; Bohemian and German, in schools, courts of justice, and in public offices.

(2) A united representation in the State Legislature of the three crown-lands, Bohemia. Moravia, and Silesia.

(3) A free local self-government.

(4) Equality of all religions.

(5) Independence and publicity of trials.

(6) Abolition of socage.

(7) Freedom of the press.

These resolutions were embodied in the three words which were taken as a motto during the revolution; viz., nationality, self-government, and political freedom.

In order that these resolutions might be properly drawn up and their scope explained, a committee of twenty-seven citizens was appointed for this task, consisting both of Germans and Bohemians, which, from the place of meeting, was called St. Vaclav’s Committee. At this time the harmony between the two nationalities was something phenomenal, and was a source of great joy to all good citizens. As the above meeting was conducted by some of the most influential citizens, the military did not interfere, although the troops were standing ready to be called out at a moment’s notice.

While these things were going on in Prague, a revolution likewise broke out in Vienna, which, however, did not go off as peaceably as the one in Bohemia. The troops trying to break up the meeting of the people, a skirmish took place, in which several persons lost their lives. This seemed but to inflame the people so that their demands upon the government became all the more peremptory, until the emperor, to prevent further bloodshed, granted some concessions. He dismissed the hated Prince Metternich, abolished the censorship of the press, permitted the organization of a home guard, and promised to grant a constitution, for which a Diet was to be called composed of delegates from all the Austrian provinces except Hungary.

When the news that the emperor promised to grant a constitution reached Prague, the city was filled with rejoicings, the people in their enthusiasm imagining that the objects of the revolution were already secured.

The petition to the emperor being duly drawn up and signed by thousands of citizens, the deputation took its departure to Vienna to lay it before the emperor, which was done on the 19th of March.

The citizens of Prague, following the example of the Viennese, organized a home guard, to which the students were also admitted, forming the Academic Legion. The main object of this organization was to prevent the rabble from committing any acts of violence, as had been, the case in Vienna. The St. Václav’s Committee, taking special care to provide work and give aid to the poor, succeeded in preserving perfect order both in Prague and in other cities.

On the 27th of March the delegation returned to Prague. The whole city, in holiday attire, turned out to welcome the delegates and to hear what success they had met in Vienna. There being no hall large enough, to accommodate the crowds of curious spectators, a meeting was called in the open air, by the statue of St. Václav, on the avenue of the same name. The archbishop and the attendant priests chanted a grand Te Deum, after which the chairman of the deputation read the decision of the emperor. Some of the demands had already been granted by the patents issued for the whole empire. Some he granted, the most important of which was the abolition of socage; and some he postponed for further consideration. From the report of the delegates it was evident that the government did not intend to grant to the Bohemians what they most desired; that is, home rule, or the privilege of being governed according to the ancient State law.

In the vast crowd assembled to hear the reading of the report, one idea took possession of all minds, and that was that the emperor was not sincere in regard to Bohemia; and the expression of joy that had but a moment before lighted every countenance, now was changed to one of sorrow and gloomy foreboding.

To allay the public discontent, another committee was appointed to draw up another petition to the court. A party of students demanded arms and ammunition from the imperial magazines, which Archduke Charles Ferdinand, the commander-in-chief, granted, wishing to avoid a crisis, and also intrusted the care of the public peace to the newly-organized legions.

In the second petition the demands of the people were more explicitly set forth, and also some changes introduced. On account of the urgency of the case, this petition was not given to the people to sign; but the committee, instead, succeeded in obtaining the signature of Count Rudolph of Stadion, then the viceroy of the kingdom. The count—at first very reluctant to sign the petition, later on wishing to show his sympathy with the popular movement—himself appointed a special committee to discuss the needed reforms. At the same time the Bohemian nobility announced to St. Václav’s Committee that they would not insist on their special privileges in the coming Diet. The second delegation to Vienna was there sustained by the action of some noblemen, who offered a similar petition with their own signatures.

At this time the city of Prague performed the first act of self-government. The mayor appointed by the government having resigned, the people elected the new aldermen, and Anton Strobach was thus chosen mayor.

The Vienna delegation returned the 11th of April, and gave the following report: The emperor promised to call a Diet, in which, besides the usual delegates, there were to be representatives from all the larger cities, and also some from the country districts; to appoint a regent as chief ruler in Bohemia; to declare the equality of the two languages—Bohemian and German. The union of Bohemia, Moravia, and Silesia was postponed for further consideration at the coming Diet. This report, although not entirely satisfactory, quieted the minds of the people, since the promised Diet gave them a hope of obtaining the rest of their demands. Further developments, however, soon showed that the government was not sincere in its concessions, and that they were merely granted to relieve the momentary pressure. One of the proofs of this was the fact that the chief command was placed into the hands of Prince Windischgratz, a proud aristocrat, hated by the people of Vienna on account of his avowed enmity to the progressive spirit of the times.

The people of Moravia, at last roused out of their lethargy by the example of the sister State, now called, a Diet, and also sent a delegation to the emperor. Some of their demands were also granted, among them the abolition of socage.

At the very time that a new day seemed to be dawning to the peoples composing the Austrian dominions, the empire itself was threatened with destruction. A delegation came from Hungary, and compelled the emperor to grant them an entirely separate and independent government. A few day after this, a revolution broke forth in Venice and Lombardy, the King of Sardinia coming to the assistance of these countries, to help them to win their independence. A similar uprising was put down by force of arms at Cracow.

But the greatest danger threatening the country was from Germany itself. Delegates from all the German States met at Frankfort, and demanded of their respective rulers a General Parliament of United Germany. Such a Parliament soon met, and proceeded to work out a form of union for the States represented, including, however, Austria, and with it Bohemia, Moravia, and Silesia. In Vienna the enthusiasm for a united Germany was so great that the students, gathering in crowds before the royal palace, succeeded in forcing the German flag into the hands of the emperor. The Frankfort delegates invited Francis Palacký, the Bohemian historian, to represent his nation in the coming Parliament; but he declined the honor, regarding the movement dangerous both to Austria and Bohemia.

The Prime Minister Pillensdorf, carried away by every new excitement, and hardly able to withstand the pressure brought to bear upon him by the students and other visionaries, ordered elections to be held in all the Austrian provinces to choose delegates to the Frankfort Parliament.

This action put an end to the good feeling between the Germans and Bohemians in Prague. The former, incited by emissaries, began to suspect every movement that the Bohemians made in regard to their nationality as an act of hostility against themselves. There was a strong party in Prague in favor of the Frankfort Parliament, and when the St. Václav’s Committee, now called the National, declared against it, the German members resigned, and formed another committee, styled the Constitutional Union. Messengers from Frankfort came to Prague, with the demand that the National Committee should adopt different views; and when it refused to do so, they went so far in their audacity as to threaten to compel them to do so at the point of the sword. This so roused the indignation of the people that the Bohemian students broke up the meeting of the Constitutional Union, which after that did not venture to hold its sittings publicly.

From this time on, Prague became the scene of continual disturbances. The young people charivaried persons obnoxious to them, and the rabble, as usual, turned against the Jews, who only escaped being plundered, by the protection of the National Guard. The press, in the excitement of the times left free, abused its newly-gained liberty, indulging in all manner of lampoons, especially against the hated officials. The country people soon caught the spirit of the cities, and sought redress for many petty grievances by unlawful and violent measures.

The efforts of the Frankfort Parliament to form a union of all the Germanic States, The Slavonic Congress.absorbing within them the various Slavonic nations of Central Europe, gave rise to a counter assembly; viz., the Slavonic Congress.

The National Committee, seeing that the government at Vienna was either unable or unwilling to protect them from the insults of the German emissaries, issued a proclamation to the Slavonic nations in the Austrian dominions to meet at Prague to discuss matters of general interest. The government, to make better provision for preserving order, appointed, in the place of Count Stadion, Count Leo Thun as chairman of the Executive Committee governing Bohemia. Count Thun, before this a member of the Executive Committee in Galicia, was a highly-popular man on account of his zeal for the national cause; consequently the people rejoiced at his appointment; but he disappointed the hopes placed in him. Neither he nor Mayor Strobach possessed that elasticity of mind that would enable them to adapt themselves to the solution of questions coming up every day from the excited populace. Strobach, becoming discouraged amid the rising difficulties, resigned, and Count Thun soon lost all popularity.

The cause of most of the trouble was the instability of the central government. Desiring to keep the favor of of all parties, especially of the students and the Germans favoring the Frankfort Parliament, the government broke the promise given the 15th of March, as well as the one given to the Prague delegation on the 8th of April, to arrange a State policy in accordance with the wishes of the several nations, and itself worked out a State system which utterly ignored the special needs of the countries constituting the Austrian Empire.

Neither the people of Prague nor those of Vienna were satisfied with the action of the government, and the latter soon expressed their indignation by violent means. Forcing their way into the royal palace, they compelled the emperor to give a promise that no State system should be adopted until the same had been formed at a General Diet composed of delegates chosen without any limitations as to the qualifications of the voters. Ferdinand, highly offended at this act of violence, left the capital, and took his departure to Innsbruck.

The news of this step created great consternation in Prague. The National Committee, the city of Prague, and other corporations, sent out deputations to the emperor, assuring him of their loyalty.

The vacillating policy of the Viennese ministry made it lose so much prestige that Count Thun, on his own responsibility, issued letters of election for members to the State Diet; but, with a strange inconsistency, also issued similar letters for the election of delegates to the Frankfort Parliament. However, little harm was done. The Bohemian citizens did not vote, and the German ones only in the towns along the boundaries. Prague itself cast only three votes. Count Thun further showed his independence of the ministry by associating with himself in the government several distinguished citizens; namely, Palacký, Rieger, Borrosche, Brauner, Strobach, and Counts Nostic and Wurmbrand. Rieger and Nostic were sent to Innsbruck to ask the emperor to sanction the policy of Thun, and to appoint a day for the calling of the Bohemian Diet.

The ministry was much offended at the actions of Count Thun, regarding them as an attempt to secure the independence of the country; and it demanded that the election to the State Diet be postponed until after the general election. The count, instead of complying with the request, postponed the elections to the Frankfort Parliament, which so exasperated the members of the ministry, that he was asked to resign his office.

In the meantime, the Slavonic Congress met in Prague, June 2d. As might be expected, the occasion was seized by the more ardent patriots to hold a grand Slavonic holiday. There were parades, illuminations, meetings for the expression of brotherly regard, high mass held in the old Slavonic dialect, a grand congregational singing of the ancient Slavonic hymn, Gospodine pomilujny! (Lord, have mercy upon us!) and, what was of most importance, meetings of the most distinguished men as to mutual needs of the nations represented.

As the doings of the Frankfort Parliament had filled the minds of the Bohemians with fear, and that with cause, so now the Germans looked at this Congress, with all the Slavonic demonstrations, with a feeling akin to terror. They imagined it to be but the outcropping of a vast panslavistic plot, aimed against the Germans of the Austrian dominions. And yet the central idea of the Congress was the necessity of preserving intact the unity of the Austrian empire.

The Congress drew up a manifesto to all European nations, explaining the true condition of the Slavonic nations; and a petition to the emperor, showing their common and special needs and desires; and an agreement to aid each other in all ways consistent with the laws of the land and the well-being of the nations in the empire.

Unfortunately, before the work of the Congress was finished, a storm burst over the city that scattered the delegates, prevented the meeting of the State Diet, and, in fact, proved the death-blow to the newly-born liberty.

When Prince Windischgratz obtained the command of the army in Prague, he at once determined to do all in his power to thwart the labors of the patriotic citizens. To this end he kept up a constant correspondence with the ministry in Vienna, as well as an understanding with some of the conservative citizens, who longed for the old order of things to return. At first he tried to overawe the people by indulging in various military demonstrations, that were not at all in harmony with the existing state of affairs. Finally a report was circulated that a plot was under way on the part of the military against the citizens, which filled the minds of the people with terror. A crisis occurred on the 12th of June, when the people were returning from a grand mass held by the statue of St. Václav, on St. Václav’s Avenue. At the close of the service, when the people dispersed, a crowd, composed mostly of students, turned in the direction of the Powder Tower, and passed the residence of the commander-in-chief. Just as they came near the place, they were met by a band of soldiers with drawn bayonets, who ordered them to turn back. In the skirmish that followed, several persons were left dead and many more wounded. The crowd, being totally unarmed, scattered in all directions.

As soon as they recovered from the panic, the students, following the example of those of Vienna, called to arms, and began to build barricades across the streets. The troops, gathering from all sides, attempted to dislodge them, and thus the city was plunged into the horrors of civil war. By evening of the same day, the barricades were all in the hands of the soldiers, and many students were taken prisoners. The attacking side, however, mourned the loss of several officers, as well as quite a number of private soldiers, and the death of Princess Windischgratz, who was shot by a stray bullet, presumably while looking out of the window.

The next day, the city authorities asked Prince Windischgratz, for a cessation of hostilities, which request he agreed to grant on condition that the barricades be removed; but as the people refused to do this, the day passed in uncertainty. During the disturbance, Count Thun had been taken prisoner by the students, but was released the following day. During the night the soldiers left the city, drawing with them the cannon, the wheels of which were muffled with straw. The next morning the people saw with consternation that the Hradschin was in possession of Windischgratz, and therefore that the city was entirely at his mercy.

In the morning, Windischgratz declared the city in a state of siege, and threatened to bombard it if the authorities refused to surrender in the time given them. The people, roused to indignation by such treachery, refused to surrender, and instead commenced to attack the Small Side. Thereupon the commander made good his threat, and commenced discharging his cannon into the Old Town. Some of the more moderate citizens then succeeded in obtaining an armistice; but when some more stray shots were fired after the cessation of hostilities, the bombardment was at once resumed, and several large buildings near the bridge were set afire.

The next day, the city was compelled to surrender unconditionally. The soldiers then re-entered the city, and Windischgratz began to arrest all suspected persons, especially those that had been members of the National Committee. A report being spread by the Royalists that there was a great Slavonic plot against the ruling house, many persons were arrested and tried, in the attempt to discover the leaders of the conspiracy. But as there was no plot, the court did not succeed in unearthing it, although it did succeed in causing a great deal of trouble and annoyance to some of the most worthy citizens.

Thus the reactionary policy was successfully introduced in Prague, and from that time on, the revolution declined, and the government gradually relapsed into its old despotism.

In a few days after the surrender of Prague to Prince Windischgratz, the elections for the General Diet were held, the election for the Bohemian Diet being indefinitely postponed. There was, therefore, nothing left to the National party but to send as able men as possible to Vienna, who should do what they could to secure for their nation some of the promised reforms.

The General Diet met in Vienna, July 18th. In the sessions, the Bohemian delegates held firmly to the principle, Equality to all nations in the Austrian monarchy, and the inviolability of the unity of the empire. The German delegates, finally becoming convinced that the policy advocated by the friends of the Frankfort Parliament would lead to the complete dissolution of the Austrian Empire, adopted the policy of the Bohemians, and also voted measures to prevent the secession of Hungary from the monarchy.

The progress made by the Diet in the working out of the needed reforms was very slow; but by the end of August the law relative to the abolition of socage was completed, and Ferdinand, returning to Vienna at this time, signed it, September 7th.

The party favoring the Frankfort Parliament, seeing that it was baffled in its designs, attempted to win its object by violence. Uniting with the Magyars in the city, they commenced a bloody revolution. Holding a special grudge against the ministry, they seized Latour, the Minister of War, and hanged him, and Bach escaped a similar fate by flight. Ferdinand again left the city, and the Imperial Diet, hindered in its proceedings by the angry mob, was soon obliged to adjourn, the delegates leaving the city and returning to their homes.

In this crisis, when Vienna was entirely in the power of a mob that favored Germany, the Austrian empire was saved from destruction through the assistance of a Slavic general. This was the brave Jelcic, the Ban of Croatia, who at this time was trying to protect the Croatians from the tyranny of the Magyars. Hearing of the revolution of Vienna, he at once started to the help of the government forces. Reaching Vienna from one side, while Windischgratz coming from Bohemia, advanced to it from the opposite direction, the two armies attacked the city and soon compelled it to surrender. After punishing some of the leaders by death, the two generals turned against Hungary, and although they did not succeed in subjugating the country, they met with considerable success, which greatly encouraged the government. This, however, instead of being a blessing proved a great evil; for the government, gaining courarge by the removal of the dangers, immediately returned to its reactionary policy. When the Diet, so to speak, was driven from Vienna, the delegates decided to continue the sessions elsewhere, and as the emperor had fled to Moravia, the Moravian town of Kremsier was selected for this purpose.

In a few days after the meeting of the Diet, Ferdinand, discouraged by the difficulties surrounding him, resigned his crown in favor of his nephew, Francis Joseph, December 1, 1848.

FRANCIS JOSEPH.

The Diet in Kremsier proceeded with its work, and soon drew up a system of government that was thoroughly democratic. But while the discussions were going on, the government had not been idle. In secret it had also drawn up a system of government, and to the amazement of the delegates brought forward the new constitution, announced it as the future law of the land, and on the same day dissolved the Diet, March 4, 1849.

According to the new constitution, the whole empire was to have a Parliament, or Reichsrath, composed of two Houses, the Higher House to be composed of prominent citizens who paid a tax of not less than 500 florins, the Lower House of delegates chosen by the people.

Francis Joseph I. The proposed Legislature was to have almost complete control of all matters relating to the realm, leaving but a nominal power to the State Diets. None of the States were satisfied with this peremptory method of settling the question; but they were now too weak to rebel against the established order.

In the meantime the new nministry began to work out a system of government that should, to some extent, fulfill the wishes of the people as expressed in their petitions of the previous year. The towns were granted a new system, leaving them considerable liberty in regard to local government.

Count Thun, minister of ecclesiastical and educational matters, wrought many improvements in both the common schools and higher institutions of learning. The university obtained a more liberal system of administration; the gymnasiums were remodeled after those of Prussia, and many Real schools were also organized. In the lower schools Bohemian was made the language of instruction.

Knight Schmerling, Minister of Justice, established a new system of procedure in courts of justice. The trials were to be public, the proceedings oral, and there was to be a jury.

For some time it seemed that the ministry had a sincere desire to introduce the needed reforms; but this favorable state of affairs was of short duration. As in the old days during the Hussite wars, when the people compelled the princes of the world to give them a fair hearing by working according to the motto, Vexatio dat intellectum, so it seems that as long as the officers of the government were harassed by disturbances and uprisings on all sides, their intellect was clear and they were ready to enter upon a policy that would have brought harmony and prosperity to the nations composing the monarchy; but no sooner was the “vexatio” removed, than the government lost its isdom and relapsed into its old despotic ways.

To the close of the year 1848 the Hungarians were completely subjugated. General Radecky, the gray-haired Bohemian veteran, won a glorious victory over the King of Sardinia, which resulted in the restitution to the empire of Venice and Lombardy. The Prussians were also compelled to make a treaty, wherein the relations between the two countries remained the same as before. These victories had the effect of turning the government from its liberal policy. If arms could do so much in the subjugation of rebellious nations, why could they not be the means of restoring the old order of affairs?

This conclusion being reached, the ministry began in a most unscrupulous manner to carry into effect their reactionary measures. About this time, Dr. Bach became the chief adviser of the emperor, and the evils of the policy introduced may be traced directly to his influence. The head of the government was Bach rather than Francis Joseph. The carrying out of the reforms that had been worked out by the other ministers was obstructed in various ways, until they became a dead letter. Other measures that had already been put into use were rescinded, with a promise that something better was in preparation; but the people waited in vain for the something better to come. Thus it was with the local system of self-government. This was soon replaced by that of State officers; and, indeed, State officers and gens d’armes swarmed everywhere until there was a system of bureaucracy far more frightful than during the most despotic times under Joseph II. Public trials and the jury were alike abolished, the courts of justice being entirely in the hands of creatures of the government.

To prevent the people from expressing their discontent, there was a most rigid censorship of the press. The Bohemian nation that, during the revolutionary period, had shown such loyalty to the reigning house, seemed now to be the special object of its suspicions. No Bohemian newspaper was allowed to be published. But except one that the government itself gave out, the worst feature of all this was, that many innocent men, being suspected of liberal views, were tried by the imperial courts of justice, and often sent to long years of imprisonment, where they either died or broke down in health as a result of cruel treatment. Among the most illustrious victims was Charles Havliček, a patriot and statesman, who for some satire written against the government, was sent to a fortress in Tyrol, where he died.

Charles Havliček (The Good). This oppressive policy for a while arrested the progress the Bohemian people had been making in their national awakening. The patriots, seeing all their earnest labors brought to naught, became disheartened, and for a while it seemed that the country would again relapse into Germanism. But the nation roused itself from this lethargy even before the fall of the ministry whose unfriendly policy was the chief cause of it.

The government of Bach fell, because its principles were contrary to the real state of affairs in the monarchy. To keep up such a system of military and bureaucratic rule required an enormous expenditure of money, which Austria could by no means furnish, the burdens of taxation having become almost unbearable. And, notwithstanding all this, the military policy of the government was by no means successful. In its war with Sardinia, by the defeat at Magenta and Solferino, it lost the beautiful province of Lombardy.