CHAPTER VIII.

"  HE next morning the boys awoke early, having had a thoroughly good night's rest. Tom, whose turn it was to go for milk, found a well-stocked farm-house, where he obtained not only milk, bread, and eggs, but a supply of butter and a chicken all ready for cooking. After breakfast the boat was put in the water, and, to the delight of all, proved to be almost as tight as she was before running into the rock. A little water came in at first under the edges of the zinc, but in a short time the wood swelled, and the leak entirely ceased.

HE next morning the boys awoke early, having had a thoroughly good night's rest. Tom, whose turn it was to go for milk, found a well-stocked farm-house, where he obtained not only milk, bread, and eggs, but a supply of butter and a chicken all ready for cooking. After breakfast the boat was put in the water, and, to the delight of all, proved to be almost as tight as she was before running into the rock. A little water came in at first under the edges of the zinc, but in a short time the wood swelled, and the leak entirely ceased.

The boat was loaded, and the boys were ready to start soon after six o'clock. There was no wind, but the two long oars, pulled one by Tom and the other by Jim, sent her along at a fine rate. They rowed until ten o'clock, resting occasionally for a few moments, and then, as there were no signs of a breeze, and as it was growing excessively hot, they went ashore, to wait until afternoon before resuming their journey.

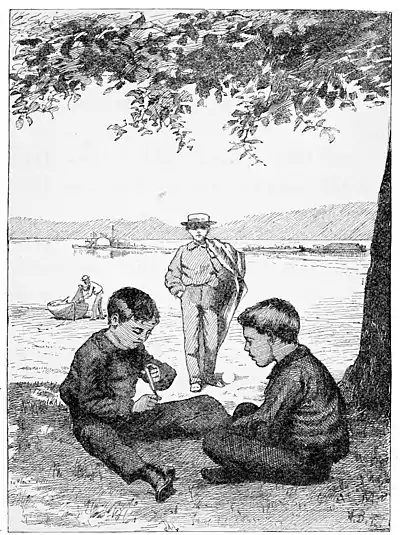

The sun became hotter and hotter. The boys tried to fish, but there was no shade near the bank of the river, and it was too hot to stand or sit in the sunshine and wait for fish to bite. They went in swimming, but the sun, beating on their heads, seemed hotter while they were in the water than it did when they were on the land. Jim and Joe tried a game of mumble-to-peg, but they gave it up long before they had reached "ears." It was probably the hottest day of the year; and as it was clearly impossible to row or to do anything else while the heat lasted, the boys brought their blankets from the boat, and, going to a grove not far from the shore, lay down and fell asleep.

They were astonished to find, when they awoke, that it was two o'clock. None of them had been ac

MUMBLE-THE-PEG.

After lunch the boys prepared to start, although there was still no wind; but when they went down to the boat they found that the sun was as hot as ever. So they returned to the shade of the grove, and made up their minds to stay there until the end of the afternoon.

"Harry," said Tom, "we've been on the river three days, and we are only a little way above Hudson. How much longer will it be before we get to Albany?"

"We ought to get there in two days more, even if we have to row all the way," replied Harry.

"And after we get to Albany, what are we to do next?"

"We are going up the Champlain Canal to Fort Edward. There we will have a wagon to carry us and the boat to Warrensburg, on the Schroon River, and will go up the river to Schroon Lake. Uncle John laid out the route for us."

"How many days will it take us to get to the lake?" asked Tom.

Harry thought awhile. "There's two days more on the Hudson, two on the canal, and maybe two on the Schroon River. And then there's a Sunday, which don't count. It'll be just a week before we get to the lake."

"I've got to be home by two weeks from next Monday," continued Tom, "so I sha'n't have much time on the lake. Can't we get along a little faster? There's a full-moon to-night, and suppose we sail all night—or row, if the wind doesn't come up."

"That's a first-rate idea," exclaimed Harry. "We can take turns sleeping in the bottom of the boat. Why, if the breeze comes up in the night, we might make twenty or thirty miles before morning."

All the boys liked the plan of sailing at night, and they resolved to adopt it. While they were yet discussing it, a light breeze sprang up, from the south as usual, and they hastened to take advantage of it. In the course of an hour more the sun began to lose its power; and when they went ashore at six o'clock to cook their supper, they had sailed about fifteen miles.

As they expected to make so much progress during the night, they were in no hurry about supper, and it was not until after seven o'clock that they again made sail. Harry divided the crew into watches—one consisting of himself and Joe Sharpe, and the other of Tom and Jim. Each watch was to have charge of the boat for three hours, while the other watch slept. At eight o'clock Tom and Jim lay down in the bottom of the boat, and Joe came aft to take Tom's customary place at the sheet. Harry, of course, steered.

All went well. The breeze was light but steady, and Harry kept the boat in the middle of the river to avoid another shipwreck. The watch below did not sleep much, for they had had a long nap at noon, and, besides, the novelty of their position made them wakeful. They had just dropped asleep when eleven o'clock arrived, and they were awakened to relieve the other watch. Tom went sleepily to the helm, and Harry and Joe gladly "turned in," and were soon fast asleep.

Tom always declares that he never closed his eyes while he was at the helm, and Jim also asserts that he was wide awake during his entire watch, though neither he nor Tom spoke for fear of waking up the other boys. It was strange that these two wide-awake young Moral Pirates did not notice that a large steamboat—one of the Albany night-boats—was in sight, until she was within a mile of them, and it is just possible that, without knowing it, they were a little too drowsy to keep a proper lookout.

As soon as Tom saw the steamboat, he remarked, "Halloo! there's one of the Albany boats," and steered the boat over toward the east shore. The breeze had nearly died away, and the Whitewing moved very slowly. The steamboat came rapidly down the river, her paddles throbbing loudly in the night air. Jim began to get a little uneasy, and said, "I hope she won't run us down." "Oh, there's no danger!" replied Tom; "we shall get out of her way easy enough." But, to his dismay, the steamboat, instead of keeping in the middle of the river, presently turned toward the east shore, as if she were bent upon running down the Whitewing. Tom was now really alarmed; and as he saw that the sail was doing very little good, he hurriedly told Jim to take down the mast and get out the oars as quick as possible. Jim rapidly obeyed the order, dropping the mast on Harry's head, and catching Joe by the nose in his search for the oars. By this time Tom had begun to hail the steamboat at the top of his lungs; but no attention was paid to him by the steamboat men, since the noise of the paddles drowned Tom's voice. Harry and Joe, who were now wide awake, saw what danger they were in, and they sprang to the oars. The steamboat was frightfully near, and still hugging the shore; but Tom called on the boys to give way with their oars, and steered straight for the shore, knowing that there must be room for the boat between the steamboat and the bank of the river, and fearing that if he steered in the opposite direction the steamboat might change her course and run them down, when they would have little chance of escape by swimming.

It was certainly very doubtful if they could avoid the steamboat, and Tom was well aware of it. He told the other boys that, if they were sure to be run down, they must jump before the steamboat struck them, and dive, so as to escape the paddles. "I'll tell you when to jump, if worst comes to worst," said he; "but don't you look around now, nor do anything but row. Row for your lives, boys." And the boys did row gallantly. Harry had a pair of sculls, and Jim had a long oar, and between them they made the boat fly through the water. As they neared the shore, it seemed to them that there was not more than three feet of space between the steamboat and the land; and Tom had almost made up his mind that the cruise was coming to a sudden end, when the great steamboat swung her head around, and drew out toward the middle of the river. She did not seem to be more than a rod from them as she changed her course, though in reality she was probably much farther off. At the same moment the Whitewing reached what appeared to be the shore, but what was really a long row of piles projecting about a foot above the water. The boys had just ceased rowing, and Tom had given the boat a sheer with the rudder, so as to bring her alongside of the piles, when the steamboat's swell, which the boys, in their excitement over their narrow escape, had totally forgotten, came rushing up, seized the boat, and threw it over the piles into a shallow and muddy lagoon.

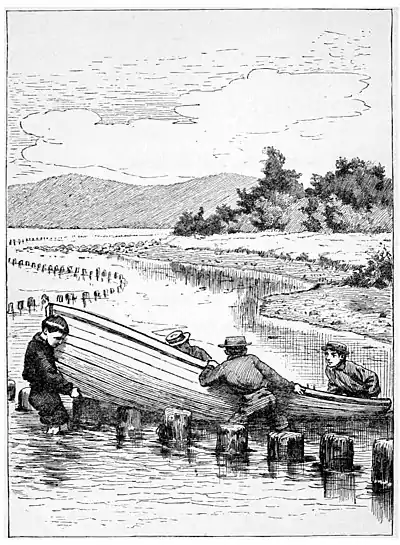

It was almost miraculous that the boat was not capsized; but she was actually lifted up and thrown over the piles, without taking more than a few quarts of spray into her. When they saw that they were absolutely safe, the boys began to wonder how in the world they could get the boat back into the river, and Jim proposed to light the lantern and see if anything was missing out of the boat, and if she had been injured.

"Now I see why the steamboat did not notice us," exclaimed Tom.

"Why?" asked all the others together.

"Because," he replied, "we have been such everlasting idiots as to sail at, night without showing a light."

LIFTING THE BOAT OVER THE PILES.