CHAPTER V.

"  T was a terrific storm. The wind swept down the river, raising a ridge of white water in its path. The rain came down harder, so the boys thought, than they had ever seen it come down before, and the glare of the lightning and the crash of the thunder were frightful.

T was a terrific storm. The wind swept down the river, raising a ridge of white water in its path. The rain came down harder, so the boys thought, than they had ever seen it come down before, and the glare of the lightning and the crash of the thunder were frightful.

"What luck it is that we got the tent pitched in time," exclaimed Joe. "We're as dry and comfortable here as if we were in a house."

"Pick your blankets up quick, boys," cried Harry. "Here's the water coming in under the tent."

Joe had boasted a little too soon. The water running down the side of the hill was making its way in large quantities into the tent. To save their clothes and blankets, the boys had to stand up and hold them in their arms, which was by no means a pleasant occupation, especially as the cold rain-water was bathing their feet.

"It can't last long," remarked Tom. "We're all right if the lightning doesn't strike us."

"Where's the powder?" asked Harry.

"Ob, it's in the flask," replied Joe, "and I've got the flask in my pocket."

"So, if the lightning strikes the tent, we'll all be blown up," exclaimed Harry. "This is getting more and more pleasant."

The boys were not yet at the end of their troubles. The rain had loosened the earth, and the tent-pins, of which only four had been used, were no longer fit to hold the tent. So, while they were talking about the powder, the tent suddenly blew down, upsetting the boys as it fell, and burying them under the wet canvas.

"Lie still, fellows," said Tom, as the other boys tried to wriggle out from under the tent. "We've got to get wet now, anyway; but perhaps, if we stay as we are, we can manage to keep the blankets dry."

The wet tent felt miserably cold as it clung to their heads and shoulders, but the boys kept under it, and held their blankets and spare shirts wrapped tightly in their arms. Luckily the storm was nearly at an end when the tent blew down, and a few moments later the rain ceased, and the crew of the Whitewing, in a very damp condition, crept out and congratulated themselves that they had escaped with no worse injury than a wet skin.

"Where are your rubber blankets?" asked Harry, presently.

"Rolled up with the other blankets," answered everybody.

"It won't do to tell when we get home," remarked Harry, "that, instead of using the water-proof blankets to keep ourselves dry, we used ourselves to keep the water-proofs dry. It's the most stupid thing we've done yet; and I'm as bad as anybody else."

"It was a good deal worse to pitch a tent without digging a trench around it," said Tom. "If I'd dug a trench two inches deep just back of that tent, not a drop of water would have run into it."

"And I don't think much of the plan of using only four pins to hold a tent down when a hurricane is coming on," said Joe.

"And I think the least said by a fellow who carries two pounds of powder in his pocket in a thunder-storm the better," added Jim.

It took some time to bale the water out of the boat, for the rain and the spray from the river had half -filled it. But the shower had cooled the air, and the boys were glad to be at work again after their confinement in the tent. They were soon ready to start ; and, rowing easily and steadily, they passed through the Highlands, and reached a nice camping spot on the east bank of the river below Poughkeepsie, before half-past five.

This time they selected a place to pitch the tent with great care. It was easy to find the high-water mark on the shore, and the tent was pitched a little above it, so as to be safe from a disaster like that of the previous night. Harry wanted it pitched on the top of a high bank; but the others insisted that, as long as they were safe from the tide, there was no need of putting the tent a long distance from the water, and that they had selected the only spot where they could have a bed of sand to sleep on.

This important business being settled, supper was the next subject of attention.

"We haven't been as regular about our meals as we ought to be," said Harry, "but it hasn't been our fault. We'll have a good supper to-night, at any rate. How would you like some hot turtle-soup?"

"Just the thing " said Joe The bread is beginning to get a little dry; but we can soak it in the soup."

"About going for milk," continued Harry; "we ought to arrange that and the other regular duties. Suppose after this we take regular turns. One fellow can pitch the tent, another can go for milk, another can get the firewood, and the other can cook. We can arrange it according to alphabetical order. For instance, Tom Schuyler pitches the tent to-night; Jim Sharpe goes for milk, Joe gets the firewood, and I cook. The next time we camp, Jim will pitch the tent, Joe will get the milk, I will get the wood, and Tom will cook. Is that fair?"

The boys said it was, and they agreed to adopt Harry's proposal. Jim went off with the milk-pail, and when the fire was ready, Harry took a can of soup and put it on the coals to be heated.

Jim found a house quite near at hand, where he bought two quarts of milk and a loaf of bread, and was back again at the camp before the soup was ready. He found the boys lying near the fire, waiting for the soup to heat and the coffee to boil.

"That soup takes a long time to heat through," said Torn. "There isn't a bit of steam corning out of it yet."

"How can any steam come out of it when it's soldered up tight," replied Harry.

"You don't mean to tell me that you've put the

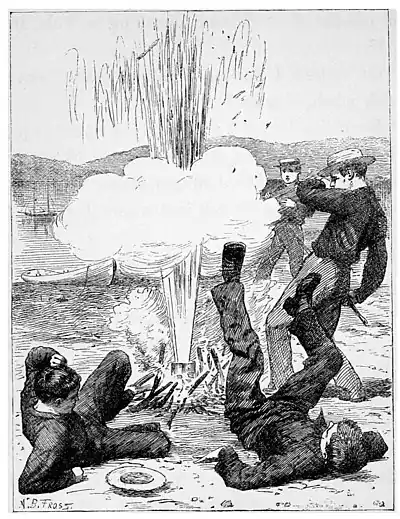

THE SOUP EXPLOSION.

"Of course I have. What on earth should I punch a hole in it for?"

"Because—" cried Tom, hastily springing up.

But he was interrupted by a report like that of a small cannon: a cloud of ashes rose over the fire, and a shower of soup fell just where Tom had been lying.

"That's the reason why," resumed Tom. "The steam has burst the can, and the soup has gone up."

"We've got another can," said Harry, "and we'll punch a hole in that one. What an idiot I was not to think of its bursting! It's a good job that it didn't hurt us. I should hate to have the newspapers say that we had been blown up and awfully mangled with soup."

The other can of soup was safely heated, and the boys made a comfortable supper. They drove a stake in the sand, and fastened the boat's painter securely to it, and then "turned in."

"No tide to rouse us up to-night, boys," said Harry, as he rolled himself in his blanket. "I sha'n't wake up till daylight."

"We'd better take an early start," remarked Tom. "We haven't got on very far because we started so late this morning. If we get off by six every morning, we can lie off in the middle of the day, and start again about three o'clock. It's no fun rowing with the sun right overhead."

"Well, it isn't more than eight o'clock now; and, if we take eight hours' sleep, we can turn out at four o'clock," said Harry. "But who is going to wake us up? Joe and Jim are sound asleep already, and I'm awful sleepy myself. I don't believe one of us will wake up before seven o'clock anyway."

Tom made no answer, for he had dropped asleep while Harry was talking. The latter thought he must be pretending to sleep, and was just resolving to tell Tom that it wasn't very polite to refuse to answer a civil question, when he found himself muttering something about a game of base-ball, and awoke, with a start, to discover that he could not possibly keep awake another moment.

The boys slept on. The moon came out and shone in at the open tent-flap, and the tide rose to high-water mark, but not quite high enough to reach the tent. By-and-by the wheezing of a tow-boat broke the stillness, and occasionally a hoarse steam-whistle echoed among the hills; but the boys slept so soundly that they would not have heard a locomotive had it whistled its worst within a rod of the tent.

The river had been like a mill-pond since the thunder - storm, but about midnight a heavy swell rolled in toward the shore. It came on, growing larger and larger, and, rushing up the little beach with a fierce roar, dashed into the tent and overwhelmed the sleeping boys without the slightest warning.