CHAPTER IV.

"  OME time in the middle of the night Joe Sharpe woke up from a dream that he had fallen into the river, and could not get out. He thought that he had caught hold of the supports of a bridge, and had drawn himself partly out of the water, but that he had not strength enough to drag his legs out, and that, on the contrary, he was slowly sinking back. When he awoke he found that he was very cold, and that his blanket felt particularly heavy. He put his hand down to move the blanket, when, to his great surprise, he found that he was lying with his legs in a pool of water.

OME time in the middle of the night Joe Sharpe woke up from a dream that he had fallen into the river, and could not get out. He thought that he had caught hold of the supports of a bridge, and had drawn himself partly out of the water, but that he had not strength enough to drag his legs out, and that, on the contrary, he was slowly sinking back. When he awoke he found that he was very cold, and that his blanket felt particularly heavy. He put his hand down to move the blanket, when, to his great surprise, he found that he was lying with his legs in a pool of water.

Joe instantly shouted to the other boys, and told them to wake up, for it was raining, and the tent was leaking. As each boy woke up he found himself as wet as Joe, and at first all supposed that it was raining heavily. They soon found, however, that no rain-drops were pattering on the outside of the tent, and that the stars were shining through the open flap. "There's water in this tent," said Tom, with the air of having made a grand discovery. "If any of you fellows have been throwing water on me, it was a mean trick," said Jim. All at once an idea struck Harry. "Boys," he exclaimed, "it's the tide! We've got to get out of this place mighty quick, or the tide will wash the tent away."

The boys sprung up, and rushed out of the tent. They had gone to bed at low-tide, and as the tide rose it had gradually invaded the tent. The boat was still safe, but the water had surrounded it, and in a very short time would be deep enough to float it. The tide was still rising, and it was evident that no time should be lost if the tent was to be saved.

Two of the boys hurriedly seized the blankets and other articles which were in the tent, and carried them on to the higher ground; while the other two pulled up the pins, and dragged the tent out of reach of the water. Then they pulled the boat farther up the beach, and, having thus made everything safe, had leisure to discover that they were miserably cold, and that their clothes, from the waist down, were wet through.

Luckily, their spare clothing, which they had used for pillows, was untouched by the water, so that they were able to put on dry shirts and trousers. Their blankets, however, had been thoroughly soaked, and it was too cold to think of sleeping without them. There was nothing to be done but to build a fire, and sit around it until daylight. It was by no means easy to collect firewood in the dark; and as soon as a boy succeeded in getting an armful of driftwood, he usually stumbled and fell down with it. There was not very much fun in this; but when the fire finally blazed up, and its pleasant warmth conquered the cold night air, the boys began to regain their spirits.

"I wonder what time it is?" said one.

Tom had a watch, but he had forgotten to wind it up for two or three nights, and it had stopped at eight o'clock. The boys were quite sure, however, that they could not have been asleep more than half an hour.

"It's about one o'clock," said Harry, presently.

"I don't believe it's more than nine," said Joe.

"We must have gone into the tent about an hour after sunset," continued Harry, "and the sun sets between six and seven. It was low-tide then, and it's pretty near high-tide now; and since the tide runs up for about six hours, it must be somewhere between twelve and one."

"You're right," exclaimed Jim. "Look at the stars. That bright star over there in the west was just rising when we went to bed."

"You ought to say 'turned in!’" said Joe. "Sailors never go to bed; they always 'turn in.’"

"Well, we can't turn in any more to-night," replied Tom. "What do you say, boys? suppose we have breakfast—it'll pass away the time, and we can have another breakfast by-and-by."

Now that the boys thought of it, they began to feel hungry, for they had had a very light supper. Everybody felt that hot coffee would be very nice; so they all went to work—made coffee, fried a piece of ham, and, with a few slices of bread, made a capital breakfast. They wrung out the wet blankets and clothes, and hung them up by the fire to dry. Then they had to collect more firewood; and gradually the faint light of the dawn became visible, before they really had time to find the task of waiting for daylight tiresome.

They decided that it would not do to start with wet blankets, since they could not dry them in the boat. They therefore continued to keep up a brisk fire, and to watch the blankets closely, in order to see that they did not get scorched. After a time the sun came out bright and hot, and took the drying business in charge. The boys went into the river, and had a nice long swim, and then spent some time in carefully packing everything into the boat. By the time the blankets were dry, and they were ready to start, the tide had fallen so low that the boat was high and dry; and in spite of all their efforts they could not launch her while she was loaded.

"We'll have to take all the things out of her," said Harry.

"It reminds me," remarked Joe, "of Robinson Crusoe that time he built his big canoe, and then couldn't launch it."

"Robinson wasn't very sharp," said Jim. "Why didn't he make a set of rollers, and put them on the boat?"

"Much good rollers would have been," replied Joe. "Wasn't there a hill between the boat and the water? He couldn't roll a heavy boat uphill, could he?"

"He could have made a couple of pulleys, and rigged a rope through them, and then made a windlass, and put the rope round it," argued Jim.

"Yes; and he could have built a steam-engine and a railroad, and dragged the boat down to the shore that way, just about as easy."

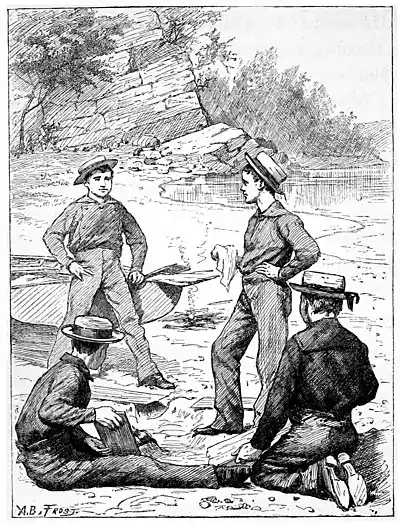

"IF YOU WANT TO DIG, DIG. I DON'T INTEND TO DO ANY MORE DIGGING."

"But we can," cried Harry. "If we just scoop out a little sand, we can launch the boat with everything in her!"

The boys liked the idea of a canal; and they each found a large shingle on the beach, and began to dig. They dug for nearly an hour, but the boat was no nearer being launched than when they began. Tom stopped digging, and made a calculation. "t will take about two days of hard work to dig a canal deep enough to float that boat. If you want to dig, dig; I don't intend to do any more digging."

When the other boys considered the matter, they saw that Tom was right, and they gave up the idea of making; a canal. It was now about ten o'clock, and they were rather tired and very hungry. A second breakfast was agreed to be necessary, and once more the fire was built up and a meal prepared. Then the boat was unloaded and launched, and the boys, taking off their shoes and rolling up their trousers, waded in the water and reloaded her. It was noon by the sun before they finally had everything in order and resumed their cruise.

There was no wind, and it was necessary to take to the oars. The disadvantage of starting at so late an hour soon became painfully plain. The sun was so nearly overhead that the heat was almost unbearable, and there was not a particle of shade. The boys had not had a full night's sleep, and had tired themselves before starting by trying to dig a canal. Of course the labor of rowing in such circumstances was very severe; and it was not long before first one and then another proposed to go ashore and rest in the shade.

"Hadn't we better keep on till we get into the Highlands. We can do it in a quarter of an hour," said Tom.

As Tom was pulling the stroke oar, and doing rather more work than any one else, the others agreed to row on as long as he would row. They soon reached the entrance to the Highlands, and landed at the foot of the great hill called St. Anthony's Nose. They were very glad to make the boat fast to a tree that grew close to the water, and to clamber a little way up the hill into the shade.

"What will we do to pass away the time till it gets cooler?" said Harry, after they had rested awhile.

"I can tell you what I'm going to do," said Tom; "I'm going to get some of the sleep that I didn't get last night, and you'd better follow my example."

All the boys at once found that they were sleepy; and, having brought the tent up from the boat, they spread it on the ground for a bed, and presently were sleeping soundly. The mosquitoes came and feasted on them, and the innumerable insects of the summer woods crawled over them, and explored their necks, shirt-sleeves, and trousers-legs, as is the pleasant custom of insects of an inquiring turn of mind.

"What's that?" cried Harry, suddenly sitting up, as the sound of a heavy explosion died away in long, rolling echoes.

"I heard it," said Joe; "it's a cannon. The cadets up at West Point are firing at a mark with a tremendous big cannon."

"Let's go up and see them," exclaimed Jim. "It's a great deal cooler than it was."

With the natural eagerness of boys to be in the neighborhood of a cannon, they made haste to gather up the tent and carry it to the boat. As they came out from under the thick trees, they saw that the sky in the north was as black as midnight, and that a thunder-storm was close at hand.

"Your cannon, Joe, was a clap of thunder," said Harry. "We're going to get wet again."

"We needn't get wet," said Tom. "If we hurry up we can get the tent pitched and put the things in it, so as to keep them dry."

They worked rapidly, for the rain was approaching fast, but it was not easy to pitch the tent on a side hill. It was done, however, after a fashion; and the blankets and other things that were liable to be injured by the wet were safely under shelter before the storm reached them.