CHAPTER II.

HEN Uncle John announced that the Department was satisfied with the ability of the captain and crew to manage the Whitewing, the day for sailing was fixed, and the boys laid in their stores. Each one had a fishing-line and hooks, and Harry and Tom each took a fishing-pole—two poles being as many as were needed, since most of the fishing would probably be done with drop-lines. Uncle John lent Harry his double-barrelled gun, and a supply of ammunition. Each boy took a tin plate, a tin cup, knife, fork, and spoon. For cooking purposes, the boat carried a coffee-pot, two tin cake -pans, which could be used as frying-pans as well as for other purposes, and two small tin pails. Harry's mother lent him several large round tin boxes, in which were stored four pounds of coffee, two pounds of sugar, a pound of Indian meal, a large quantity of crackers, some salt, and a little pepper. The rest of the provisions consisted of two cans of soup, two cans of corned-beef, a can of roast-beef, two small cans of devilled chicken, four cans of fresh peaches, a little package of condensed beef for making beef- tea, and a cold boiled ham. The boat was furnished with an A tent, four rubber blankets and four woollen blankets, a hatchet, a quantity of spare cordage, a little bull's-eye lantern, which burnt olive-oil, a few copper nails, a pair of pliers, and a small piece of zinc and a little white-lead for mending a leak. Of course there was a bottle of oil for the lantern; and Mrs. Schuyler added a little box of pills and a bottle of "Hamlin's Mixture" as medical stores. The boys wore blue flannel trousers and shirts, and each one carried an extra pair of trousers, and an extra shirt instead of a coat. These, with a few pairs of stockings and two or three handkerchiefs, were all the clothing that they needed, so Uncle John said; though, the boys had imagined that they must take at least two complete suits. He showed them that two flannel shirts worn at the same time, one over the other, would be as warm as one shirt and a coat, and that if their clothing became wet, it could be easily dried. "Flannel and the compass are the two things that are indispensable to navigation," said Uncle John: "if flannel shirts had not been invented, Columbus would never have crossed the Atlantic." Perhaps there was a little exaggeration in this; but when we remember that flannel is the only material that is warm in cold weather and cool in hot weather, and that dries almost as soon as it is wrung out and hung in the wind, it is difficult to see how sailors could do without it.

HEN Uncle John announced that the Department was satisfied with the ability of the captain and crew to manage the Whitewing, the day for sailing was fixed, and the boys laid in their stores. Each one had a fishing-line and hooks, and Harry and Tom each took a fishing-pole—two poles being as many as were needed, since most of the fishing would probably be done with drop-lines. Uncle John lent Harry his double-barrelled gun, and a supply of ammunition. Each boy took a tin plate, a tin cup, knife, fork, and spoon. For cooking purposes, the boat carried a coffee-pot, two tin cake -pans, which could be used as frying-pans as well as for other purposes, and two small tin pails. Harry's mother lent him several large round tin boxes, in which were stored four pounds of coffee, two pounds of sugar, a pound of Indian meal, a large quantity of crackers, some salt, and a little pepper. The rest of the provisions consisted of two cans of soup, two cans of corned-beef, a can of roast-beef, two small cans of devilled chicken, four cans of fresh peaches, a little package of condensed beef for making beef- tea, and a cold boiled ham. The boat was furnished with an A tent, four rubber blankets and four woollen blankets, a hatchet, a quantity of spare cordage, a little bull's-eye lantern, which burnt olive-oil, a few copper nails, a pair of pliers, and a small piece of zinc and a little white-lead for mending a leak. Of course there was a bottle of oil for the lantern; and Mrs. Schuyler added a little box of pills and a bottle of "Hamlin's Mixture" as medical stores. The boys wore blue flannel trousers and shirts, and each one carried an extra pair of trousers, and an extra shirt instead of a coat. These, with a few pairs of stockings and two or three handkerchiefs, were all the clothing that they needed, so Uncle John said; though, the boys had imagined that they must take at least two complete suits. He showed them that two flannel shirts worn at the same time, one over the other, would be as warm as one shirt and a coat, and that if their clothing became wet, it could be easily dried. "Flannel and the compass are the two things that are indispensable to navigation," said Uncle John: "if flannel shirts had not been invented, Columbus would never have crossed the Atlantic." Perhaps there was a little exaggeration in this; but when we remember that flannel is the only material that is warm in cold weather and cool in hot weather, and that dries almost as soon as it is wrung out and hung in the wind, it is difficult to see how sailors could do without it.

The boys agreed very readily to take with them only what Uncle John advised. Tom Schuyler, however, was very anxious to take a heavy iron vise, which he said could be screwed on the gunwale of the boat, and might prove to be very useful, although he could not say precisely what he expected to use it for. Joe Sharpe also wanted to take a baseball and bat, but neither the vise nor the ball and bat were taken.

The Whitewing started from the foot of East 127th Street, on a Monday morning in the middle of July, at about nine o'clock. Quite a small crowd of friends were present to see the boys off, and the neat appearance of the boat and her crew attracted the attention of all the idlers along the shore. When all the cargo was stowed, and everything was ready, Uncle John called the boys aside, and said, "Now, boys, you must sign the articles."

"What are articles?" asked all the boys at once.

"They are certain regulations, which every respectable pirate, or any other sailor for that matter, must agree to keep when he joins a ship. I'll read the articles, and if any of you don't like any one of them say so frankly, for you must not begin a cruise in a dissatisfied state of mind. Here are the articles:

"‘I. We, the captain and crew of the Whitewing, promise to decide all disputed questions by the vote of the majority, except questions concerning the management of the boat. The orders of the captain, in all matters connected with the management of the boat, shall be promptly obeyed by the crew."

"Now, if anybody thinks that the captain should not have the full control of the boat, let him say so at once. Very likely the captain will make mistakes; but the boat will be safe even if the crew obeys a wrong order, than it would be if every order should be debated by the crew. You can't hold town-meetings when you are afloat. Harry, I think, understands pretty well how to sail the boat. Will you agree to obey his orders?"

All the boys said they would; and Joe Sharpe added that he thought the captain ought to have the right to put mutineers in irons.

"That, let us hope, will not be necessary," said Uncle John. " Now listen to the second article:

"‘II. We promise not to take corn, apples, or other property without permission of the owner.'

"You will very likely camp near some field where corn, or potatoes, or something eatable, is growing. Many people think there is no harm in taking a few ears of corn or a half-dozen apples. I want you to remember that to take anything that is not your own, unless you have permission to do so, is stealing. It's an ugly word, but it can't be smoothed over in any way. Do you object to this article?"

Nobody objected to it. "We're moral pirates, Uncle John," said Tom Schuyler, "and we won't disgrace the Department by stealing."

"I know you would not, except through thoughtlessness. Now these are all the articles. I did think of asking you not to quarrel or to use bad language, but I don't believe it is necessary to ask you to make such a promise, and if it were, you probably would not keep it. So, sign the articles, give them to the captain, and take your stations."

The articles were signed. The captain seated himself in the stern-sheets, and took the yoke-lines. The rest took their proper places, and Joe Sharpe held the boat to the dock by the boat-hook. "Are you all ready?" cried Uncle John. "All ready, sir!" answered Harry. "Then give .way with your oars! Good-bye, boys, and don't forget to send reports to the Department."

The boat glided away from the shore with Tom and Jim each pulling a pair of sculls. The group on the dock gave the boys a farewell cheer, and in a few moments they' were hid from sight by the Third Avenue bridge. The tide was against them, but the day was a cool one for the season, and the boys rowed steadily on in the very best of spirits. There was a light south wind, but, as there were several bridges to pass, Harry thought it best not to set the sail before reaching the Hudson River. It required careful steering to avoid the steamboats, bridge-piles, and small boats; but the Whitewing was guided safely, and her signal—a red flag with a white cross—floated gayly at the bow.

Uncle John had made one serious mistake: he had forgotten all about the tide, and never thought of the difficulty the boys would find in passing Farmers-bridge with the tide against them. They had passed High Bridge, and had entered a part of the river with which the boys were not familiar, when Joe Sharpe suddenly called out, "There's a low bridge right ahead that we can't pass." A few more strokes of the oars enabled Harry to see a long low bridge, which completely blocked up the river except at one place, that seemed not much wider than the boat. Through this narrow channel the tide was rushing fiercely, the water heaping itself up in waves that looked unpleasantly high and rough. The boat was rowed as close as possible to the opening under the bridge; but the current was so strong that the boys could not row against it, and even if they had been able to stem it, the channel was too narrow to permit them to use the oars.

Harry ordered the boat to be rowed up to the bridge at a place where there was a quiet eddy, and all the crew went ashore to contrive some way of overcoming the difficulty. Presently Harry thought of a plan. "If we could get the painter under the bridge, we could pull the boat through easy enough if there was nobody in her."

"That's all very well," said Joe, "but how are you going to get the painter through?"

"I know," cried Jim. "Let's take a long piece of rope and drop it in the water the other side of the bridge. The current will float it through, and we can catch it and tie it to the painter."

The plan seemed a good one; and so the boys took a piece of spare rope from the boat, tied a bit of board to one end of it for a float, dropped the float into the water, and held on to the other end of the rope. When the float came in sight below the bridge they caught it with the boat-hook, and, throwing away the piece of board, tied the rope to the painter. "Now let Joe Sharpe get in the bow of the boat, to keep her from running against anything, and we'll haul her right through," exclaimed Harry.

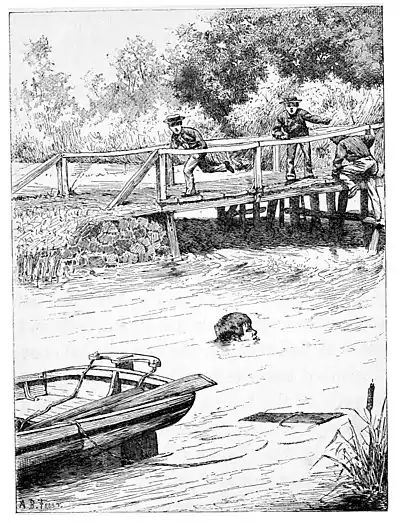

Joe took his place in the bow, and, pushing the boat off, let her float into the current. Then the three other boys pulled on the rope, and were delighted to see the boat glide under the bridge. Suddenly Joe gave a wild yell. "She's sinking, boys!" he cried: "let go the rope, or I'll be drowned!" The boys, terribly frightened, dropped the rope, and in another minute the boat floated back on the current, half full of water, and without Joe. Almost as soon as it came in sight, Harry had thrown off his shoes and jumped into the river.

HARRY SWIMS FOR THE EDDY.