THE MORAL PIRATES.

CHAPTER I.

"  HE truth is, John," said Mr. Wilson to his brother, "I am troubled about my boy. Here it is the first of July, and he can't go back to school until the middle of September. He will be idle all that time, and I'm afraid he'll get into mischief Now, the other day I found him reading a wretched story about pirates. Why should a son of mine care to read about pirates?"

HE truth is, John," said Mr. Wilson to his brother, "I am troubled about my boy. Here it is the first of July, and he can't go back to school until the middle of September. He will be idle all that time, and I'm afraid he'll get into mischief Now, the other day I found him reading a wretched story about pirates. Why should a son of mine care to read about pirates?"

"Because he's a boy. All boys like piratical stories. I know, when I was a boy, I thought that if I could be either a pirate or a stage-driver I should be perfectly happy. Of course you don't want Harry to read rubbish; but it doesn't follow because a boy reads stories about piracy, that he wants to commit murder and robbery. I didn't want to kill anybody: I wanted to be a moral and benevolent pirate. But here comes Harry across the lawn. What will you give me if I will find something for him to do this summer that will make him forget all about piracy?"

"I only wish you would. Tell me what your plan is."

"Come here a minute, Harry," said Uncle John. "Now own up; do you like books about pirates?"

"Well, yes, uncle, I do."

"So did I when I was your age. I thought it would be the best fun in the world to be a Red Revenger of the Seas."

"Wouldn't it, though!" exclaimed Harry. "I don't mean it would be fun to kill people, and to steal watches, but to have a schooner of your own, and go cruising everywhere, and have storms and—and—hurricanes, you know."

"Why shouldn't you do it this summer?" asked Uncle John. "If you want to cruise in a craft of your own, you shall do it; that is, if your father doesn't object. A schooner would be a little too big for a boy of thirteen; but you and two or three other fellows might make a splendid cruise in a row-boat. You could have a mast and sail, and you could take provisions and things, and cruise from Harlem all the way up into the lakes in the Northern woods. It would be all the same as piracy, except that you would not be committing crimes, and making innocent people wretched."

"Uncle John, it would be just gorgeous! We'd have a gun and a lot of fishing-lines, and we could live on fish and bears. There's bears in the woods, you know."

"You won't find many bears, I'm afraid; but you would have to take a gun, and you might possibly find a wild-cat or two. Who is there that would go with you?"

"Oh, there's Tom Schuyler, and Joe and Jim Sharpe; and there's Sam M'Grath—though, he'd be quarrelling all the time. Maybe Charley Smith's father would let him go. He is a first-rate fellow. You'd ought to see him play base-ball once!"

"Three boys besides yourself would be enough. If you have too many, there will be too much risk of quarrelling. There is one thing you must be sure of—no boy must go who can't swim."

"Oh, all the fellows can swim, except Bill Town. He was pretty near drowned last summer. He'd been bragging about what a stunning swimmer he was, and the boys believed him; so one day one of the fellows shoved him off the float, where we go in swimming at our school, and he thought he was dead for sure. The water was only up to his neck, but he couldn't swim a stroke."

"Well, if you can get three good fellows to go with you—boys that you know are not blackguards, but are the kind of boys that your father would be willing to have you associate with—I'll give you a boat and a tent, and you shall have a better cruise than any pirate ever had; for no real pirate ever found any fun in being a thief and a murderer. You go and see Tom and the Sharpe boys, and tell them about it. I'll see about the boat as soon as you have shipped your crew."

"You are quite sure that your plan is a good one?" asked Mr. Wilson, as the boy vanished, with sparkling eyes, to search for his comrades. "Isn't it very risky to let the boys go off by themselves in a boat. Won't they get drowned?"

"There is always more or less danger in boating," replied Uncle John; "but the boys can swim; and they cannot learn prudence and self reliance without running some risks. Yes, it is a good plan, I am sure. It will give them plenty of exercise in the open air, and will teach them to like manly, honest sports. You see that the reason Harry likes piratical stories is his natural love of adventure. I venture to predict that if their cruise turns out well, those four boys will think stories of pirates are stupid as well as silly."

So the matter was decided. Harry found that Tom Schuyler and the Sharpe boys were delighted with the plan, and Uncle John soon obtained the consent of Mr. Schuyler and Mr. Sharpe. The boys immediately began to make preparations for the cruise; and Uncle John bought a row-boat, and employed a boat-builder to make such alterations as were necessary to fit his for service.

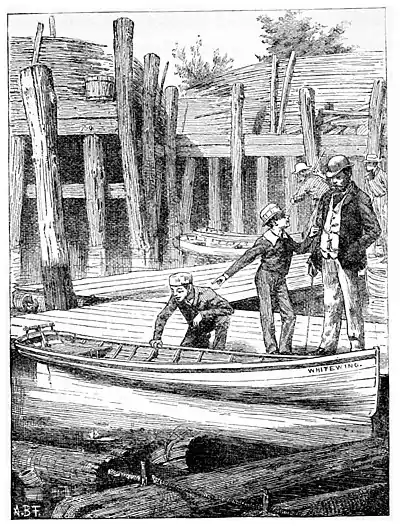

The boat was what is called a Whitehall row-boat. She was seventeen feet long, and rowed very easily, and she carried a small mast with a spritsail. By Uncle John's orders an air-tight box, made of tin, was fitted into each end of the boat, so that, even if she were to be filled with water, the air in the tin boxes would float her. She was painted white outside, with a narrow blue streak, and dark brown inside. Harry named her the Whitewing; and his mother made a beautiful silk signal for her, which was to be carried at the sprit when under sail, and on a small staff at the bow of the boat at other times. For oars there were two pairs of light seven

THE "WHITEWING" AT HARLEM.

Harry could row very fairly, for he belonged to a boat-club at school. It was not very much of a club; but then the club-boat was not very much of a boat, being a small, flat-bottomed skiff, which leaked so badly that she could not be kept afloat unless one boy kept constantly at work bailing. However, Harry learned to row in her, and he now found this knowledge very useful. He was anxious to start on the cruise immediately, but his uncle insisted that the crew must first be trained. "I must teach you to sail, and you must teach your crew to row," said Uncle John. "The Department will never consent to let a boat go on a cruise unless her commander and her crew know their duty.'

"What's the Department?" asked Harry.

"The Navy Department in the United States service has the whole charge of the Navy, and sends vessels where it pleases. Now, I consider that I represent a Department of Moral Piracy, and I therefore superintend the fitting out of the Whitewing. You can't expect moral piracy to flourish unless you respect the Department, and obey its orders."

"All right, uncle," replied Harry. "Of course the Department furnishes stores and everything else for a cruise, doesn't it?"

"I suppose it must," said his uncle, laughing. "I didn't think of that when I proposed to become a department."

The boys met every clay at Harlem and practised rowing. Uncle John taught them how to sail the boat, by letting them take her out under sail when there was very little breeze, while he kept close along-side in another boat very much like the Whitewing. Harry sat in the stern-sheets, holding the yoke-lines. Tom Schuyler, who was fourteen years old, and a boy of more than usual prudence, sat on the nearest thwart and held the sheet, which passed under a cleat without being made fast to it, in his hand. Next came Jim Sharpe, whose business it was to unship the mast when the captain should order sail to be taken in; and on the forward thwart sat Joe Sharpe, who was not quite twelve, and who kept the boat-hook within reach, so as to use it on coming to shore. The boys kept the same positions when rowing, Tom Schuyler being the stroke. Uncle John told them that if every one always had the same seat, and had a particular duty assigned to him, it would prevent confusion and dispute, and greatly increase the safety of the vessel and crew.

It was not long before Harry could sail the boat nicely, and the others, by attending closely to Uncle John's lessons, learned almost as much as their young captain. So far as boat-sailing can be taught in fair weather, Harry was carefully and thoroughly taught in six or seven lessons, and could handle the Whitewing beautifully; but the ability to judge of the weather, to tell when it is going to blow, and how the wind will probably shift, can of course be learned only by actual experience.