THE HOUSE OF DETENTION.

by clifford ashdown.

lang, clang! Clang-a-clang, clang!

lang, clang! Clang-a-clang, clang!

As the bell continued to ring Mr. Pringle started from an unrestful slumber, and, sitting up in bed, stared all around. Everything was so painfully white that his eyes closed spasmodically. White walls, white vaulted ceiling, even the floor was whitish-coloured—all white, but for the black door-patch at one end, and on this he gazed for respite from the glare. Slowly he took it all in—the bare table-slab, the shelf with its little stack of black volumes, the door, handleless and iron-sheeted, above all the twenty-four little squares of ground-glass, with their horizontal bars broadly shadowed in the light of the winter morning.

It was no dream, then, he told himself. The thin mattress, only a degree less harsh than the plank bed beneath, was too insistent, obstinately as he might close his eyes to all beside. And, as he sat, the events of the last six and thirty hours came crowding through his memory. How clearly he saw it all! Not a detail was missing. Again he stood by the riverside, the bare trees dripping in the mist; again he saw the ingots, and lent unwilling aid to save them, fingered the contemptuous vails, sole profit of their discovery. He was crossing the bridge; beyond shone the lights of the tavern, and there within he saw the frowsy crowd of loafers, and the barman proving the base coin he innocently tendered. And then came the arrest, the police cell, the filthy sights and sounds, the court with its sodden, sickening atmosphere, and, last of all, the prison. What a trap had he, open-eyed, walked into! For a second he ground his teeth in impotent fury.

The bell ceased. Dejectedly he rose, wondering as to the toilet routine of the establishment. Shaving was not to be thought of, he supposed, but enforced cleanliness was a thing he had read of somewhere. How long would last night's bath stand good for? He looked at the single coarse brown towel and shuddered. Footsteps approached; he heard voices and the jingling of keys, then the lock shot noisily, and the door was flung open.

"Now, then, put out your slops and roll your bedding up."

Pringle obeyed, but his bed-making was so lavish of space that when the warder peeped in again, some ten minutes later, he regarded the heap with a condescending grin, and presently returned with a prisoner who deftly rolled the sheets and blankets into a bundle whose end-on view resembled a variegated archery target. Then the hinges creaked once more, the lock snapped, and Pringle was left to his meditations. They were not of a cheerful nature, and it was with an exceeding bitter smile that he set himself to seriously review his position. Already had he decided that to reveal himself as the proprietor of that visionary literary agency in Furnival's Inn would only serve to increase the suspicion that already surrounded him, while availing nothing to free him from the present charge—if even it did not result in fresh accusations! On the other hand, unless he did so he could see no way of obtaining any money from his banker's so to avail himself of the very small loophole of escape which a legal defence might afford.

He had one consolation—a very small one, it is true. Money is never without its uses, and it was with an eye to future contingencies that he had managed to secrete a single half-sovereign on first arriving at the gaol. Whilst waiting, half-undressed, to enter the searching room, he bethought him of a strip of old-fashioned court-plaster which he was accustomed to carry in his pocket-book. He took it out, and, waiting his opportunity, stuck half a sovereign upon it and then pressed the strip against his shin, where it held fast.

"What's that?" inquired a warder a few minutes later, as Pringle stood stripped beneath a measuring gauge.

"I grazed my shin a couple of days ago," said he glibly.

"Graze on right shin!" repeated the warder mechanically to a colleague who was booking Pringle's description; and that was how the coin escaped discovery such time as he was being measured, weighed, searched, examined, and made free of the House of Detention. As he paced up and down the cell, occasionally fingering the little disc in his pocket, its touch did something to leaven his first sensations of helplessness, but they returned with pitiless logic so soon as he thought of escape. Bribery with such a sum was absurd, and he saw only too plainly that the days of Trenck and Casanova were gone for ever.

Chafing at the thought of his sorry fate, Pringle turned for distraction to the inscriptions which on all sides adorned the plaster walls. They were scarcely so ornate as those existing in the Tower, and their literary merit was of the scantiest; nevertheless they were not without a human interest, especially to a fellow-sufferer like Pringle. The first he lighted on appeared to be the record of a deserter: "Alf. Toppy out of Scrubbs 2nd May, now pulled for deserting from 2nd Batt. W. Norfolk." "H. Allport" informed all whom it might concern that he was "pinched for felony." Another soldier—it is to be hoped not a criminal—was indicated by the simple record, "Johore, Chitral, Rawal Pindi." One prisoner had summed up his self-compassion in the ejaculation, "Poor old Dick!" "Cheer up, mate, you'll be out some day," was no doubt intended to be comforting, whilst there was a suggestion of tragedy in the statement, "I am an innocent man charged with felony by an intoxicated woman." It seemed to be the felonious etiquette for prisoners to give their addresses as well as their names—thus, "Dave Conolly from Mint Street." "Dick Callaghan, Lombard Street, Boro, anyone going that way tell Polly Regan I expect nine moon," set Pringle wondering why on earth Dick had not written to Polly and delivered his message for himself. An ingenuous youth was "Willie, from Dials, fullied for taking a kettle without asking for it," with his artless postscript, "only wanted to know the time," but perhaps he passed for a humorist among his acquaintances, while "Darky, from Sailor's kip the Highway, nicked for highway robbery with violence," had a matter-of-fact ruffianism about it which spoke for itself.

From these sordid archives Pringle turned to the printed rules hanging from a peg in the cell, but they were couched in such an aridly official style as to remind him but the more cruelly of his position, and in considerable depression he resumed his now familiar tour—four paces to the window, a turn, and four paces back again, which was the utmost measure of the floor space. He had almost ceased to regard any plan of escape as feasible, when the idea of Freemasonry occurred as a last resort. Amongst his other studies of human nature Pringle had not neglected the mummeries of The Craft; he had even attained the eminence of a "Grand Zerubbabel." Now, he thought, was the time to test the efficacy of the doctrines he had absorbed and expounded; he would try the effect of masonic symbolism upon the warder. Soon again the keys rattled and the doors banged; nearer came the sounds, the echoes louder, but now there was a clattering as of tinware. The door was flung open, the warder took a small cube loaf of brown bread from the tray carried by a prisoner, and slapped it, with a tin resembling a squat beer-can, down on the table board. The tin was full of hot cocoa, and, quickly raising it with a peculiar motion of the hand, Pringle inquired genially, "How old is your mother?"

The warder stopped in the act of shutting the door; he pulled it open again, and glared speechless at the audacious questioner. For quite a minute he stood; then, with an accent which his emotion only rendered the purer, he growled:

"None of yer larrrks now, me man!"

As the door slammed Pringle mechanically tore the coarse brown bread into fragments, and soaking them in the cocoa, swallowed them unheedingly. His last scheme had gone the same road as its predecessors, and he no longer attempted to blind himself to the consequences. He scarcely noticed when the breakfast-ware was collected, silently handing out his tins in obedience to the summons. He was still sitting on the stool, with eyes staring at the frosted windows which his thoughts saw far through and beyond, when the eternal unlocking

"'LOST ANYTHING?' ENQUIRED THE BIG MAN" (p. 629).

began again. Listlessly he heard a voice repeating something at every door; he did not catch the words, but there was a tramp of many feet, and a bell was ringing. The voice grew louder; now it was at the next cell. He stood up.

"Chapel!"

Pringle stared at the warder—a fresh one this time.

"Get yer prayer-book and 'ymn-book, an' come to chapel! Put yer badge on," he added, looking back for a minute before continuing his monotonous chant.

Pringle picked up the black volumes and sent an inquiring glance around for the "badge." Prisoner after prisoner defiled past the open door as he waited; then all at once he saw the warder's meaning. Each man displayed a yellow badge upon his breast, and, looking round again, he saw, dangling upon his own gas-burner, a similar disc of felt, with the number of the cell stamped upon it. Hanging the tab upon his coat button, Pringle entered a gap in the procession duly labelled "B.3.6." for the occasion. Right overhead an endless column marched; on the gallery below he saw another, and all around was a rhythmic tramp—tramp in one and the same direction. Down a slope of stairs they went, across a flying bridge, and then along a gallery whose occupants had preceded them. Tramp, tramp; tramp, tramp. Another bridge, and then a door opened into a huge barn of a hall. Backless forms were ranged in long rows over the wooden floor, with here and there a little pew-like desk, from which the warders piloted their charges to their seats. The prisoner ahead of him was the end man of his bench, and Pringle, motioned to the next one, headed the file along it and sat down by the wall at the far end, with a warder in one of the little pews just in front.

"What yer in for, guv'nor?" asked someone in a husky growl.

Pringle looked round, but his immediate neighbour was glaring stolidly at the nearest warder, whose eye was upon them, and there was no one else within speaking distance but a decrepit old creature, obviously very deaf, on the row behind, and beyond him again a man of apparent education wearing a frock coat. From neither of these could such an inquiry have proceeded.

"Eyes front there! Don't let me catch you looking round again." It was the warder who spoke in peremptory tones, and Pringle started at the words like a corrected schoolboy.

"Hymn number three."

The chaplain had taken his stand by the altar, and the opening bars of Bishop Ken's grand old hymn sounded from the organ. There was a rustle and shuffling of many feet as the whole assembly rose, the organist started the singing, and the many-voiced followed on with a roar which could not wholly slaughter the melody. Half-way through the first verse Pringle felt a nudge in the ribs, and, barely inclining his head, caught the eye of his stolid neighbour as it closed in a grotesque wink. Keeping one eye on the little pew in front the man edged towards him, and repeated, in a sing-song which fairly imitated the air of the hymn:

"What yer in for, matey?"

Taking his cue, Pringle chanted back:

"Snide coin," and then a strange duet was sung to the old Genevan air.

"Fust time?"

"Yes."

"Do a bloke a turn?"

"What's that?"

"Change badges—I'll tell yer why at exercise presently. Won't 'urt you, an' do me a sight er good!"

The hymn ceased, and the chaplain began to intone the morning prayers. As they all sat down, Pringle's neighbour dropped his badge on the floor, and, pretending to reach for it, motioned to him to exchange.

The warder's attention was elsewhere, and Pringle obligingly re-labelled himself "C.2.24."

A short and somewhat irrelevant address, another hymn, and the twenty minutes' service was over. As bench after bench emptied, the monotonous tramp again echoed through the bare chamber, and a dusty haze rose and obscured the texts upon the altar. It was a single long procession that snaked round and round the corridors, and, descending by a fresh series of stairways and bridges, disappeared far below in the basement. The lower they got, the atmosphere became sensibly purer and less redolent of humanity, until at the very bottom Pringle felt a rush of air, welcome for all its coldness, and there, beyond an open grille, was an expanse of green bordered by shrubs, and, above all, the cheery sunlight.

"And earth laughed back at the day," he murmured.

The grass was cut up by concentric rings of flagstones, and round these the prisoners marched at a brisk rate. Between every two rings were stone pedestals, each adorned with a warder, who from this elevation endeavoured to preserve a regulation space between the prisoners—that is to say, when he was not engaged in breathing almost equally futile threatenings against the conversation which hummed from every man who was not immediately in front of him. And what a jumble of costumes! Tall hats mingled with bowlers and seedy caps that surely no man would pick from off a rubbish heap. Here the wearer of a frock-suit followed one who was literally a walking rag-shop; and, conspicuous among all, with its ever-rakish air in the sober day-time, an opera hat spoke of hilariously twined vine-leaves.

"Thankee, guv'nor," came a hoarse whisper from behind Pringle; "yer done me a good turn, yer 'ave so!"

The speaker was slight and sinuously active, with a cat-like gait—a typical burglar; also his hair was closely cropped in the style of the New Cut, which is characterised by a brow-fringe analogous to a Red Indian's scalp-lock, being chivalrously provided for your opponent to clutch in single combat.

"What do you want my badge for?" inquired Pringie with less artistic gruffness.

"Why, the splits'll be 'ere in a minute ter look at us—bust 'em! An' I'll be spotted—what ho! Well, they'll take my number from this badge o' yourn, 'B.3.6.,' an' they’ll look up your name an' think it's a alias of mine—see? An' then they’ll go an' enter all my convictions 'gainst you—haw, haw!"

"Against me! But, I say, you know——"

"Don't you fret—it'll do you no 'arm! Now when I goes up on remand ter-morrer there won't be nothing so the beak'll let me off light 'stead o' bullyin' me———"

"Yes, yes; I see where you come in right enough," interrupted Pringle. "But what about me?"

"No fear, I tells yer strite. When yer goes up again, if the split ain't found out 'is mistake an goes ter say anythink 'gainst yer respectability, jest you sing out loud an' say it's all a bit o' bogie—see? Then the split'll see it's not me, an' 'e'll 'ave ter own up, an' p'raps the beak'll be that concerned for yer character bein' took away that he'll———"

"Halt!"

Pringle, in amused wonderment at the cleverness of an idea founded, like all true efforts of genius, on very simple premises, walked into the man ahead of him, who had stopped at the word of command. Those in the inner circle were being moved into the outermost one, and there the whole gathering was packed close and faced inwards. Measured footsteps were now audible; but when the leaders of this new contingent came in view it was clear that whatever else they might be they were certainly not a fresh batch of prisoners. For one thing, they wore no badges; moreover, they conversed freely as they drew near. Well set up, and with a carriage only to be acquired by drilling, they displayed a trademark in their boots of a uniform type of stoutness.

"'Tecs, the swabs!" was the quite superfluous remark of Pringle's neighbour. Along the line they passed, scanning each man’s features, now exchanging a whispered comment, and anon making an entry in their pocket-books. Pringle himself was passed by indifferently, but it was quite otherwise with the wearer of badge "B.3.6." He, evidently a born actor, underwent the scrutiny with an air of profound indifference, which he managed to sustain even when one of the police returned for a second look at his familiar features.

"Forward!"

As the recognisers left the yard the prisoners were sorted out again, and resumed their march round the paved circles.

"That's a bit of all right, guv'ner!" And Pringle's new friend chuckled as he spoke. "Haw, haw! See that split come ter 'ave another look at me? Strite, I nearly busted myself tryin' not ter laugh right out! Shouldn't I like ter see the bloke's face when yer goes up—oh, daisies! Yer never bin copped afore?"

"No. Is there any chance of getting out?"

"What—doin' a bolt? Bless yer innercent young 'art, not from a stir like this! Yer might get up a mutiny, p'raps," he reflected, "so's yer could knock the screws[1] out. But 'ow are yer ter do that when yer never gets a chance ter 'ave a jaw with more than one at a time? There's the farm now," indicating an adjacent building with a jerk of the head.

"The what?"

"'Orspital. If yer feel down on yer luck yer might try ter fetch it, p'raps. But it's no catch 'ere where yer've no work and grubs yerself if yer like. Now, when yer've got a stretch the farm's clahssy."

Again the bell rang, and the spaces grew wider as the prisoners were marched off by degrees. On the stairs, as they went in, Pringle and his new friend exchanged badges, and the old prisoner, with a muttered "Good luck," passed to his own side of the gaol and was seen no more.

Back in the solitude of his cell Pringle found plentiful matter for thought. The events of the morning had enlarged his mental horizon, and roused fresh hopes of escaping the fate that menaced him. As his long legs measured the cell—one, two, three, four, turn at the window, one, two, three, four, round again at the door—so lightened was his heart that he once caught himself in the act of whistling softly, while the hours flew by unnoticed. He swallowed

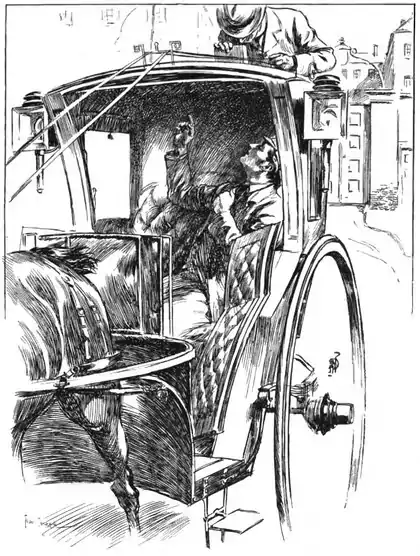

"'HALF A SOVEREIGN IF YOU DO IT QUICKLY'" (p. 631).

his dinner almost without tasting it, and the clatter of supper tins was all that reminded him that he had eaten nothing for five hours. He was not conscious of much appetite; after all, haricot beans are filling, and a meal more substantial than the pint of tea and brown loaf might have been thrown away upon him. With supper the gas had been kindled, and as he sat and munched his bread at the little table, the badge suspended on the bracket shone golden in the light. Since morning he had endowed it with a special interest—indeed, it largely inspired the thoughts which now cheered him. True, it was not a talisman at whose approach the prison doors would open wide, but it had taught him the important fact that the prisoners were known less by their faces than by the numbers of their cells. Escape seemed less and less remote, when a plan, bold and hazardous in its idea, crystallised from out the crude mass of projects with which his brain seethed. This was the plan—he would lag behind after service in chapel the next morning, conceal himself in a warder's pew, and lie in wait for the first official who might enter the chapel—such a one, in the graphic phrase of his disreputable friend, he would "knock out," and, seizing his keys and uniform, would explore the building. It would be too daring to attempt the passage of the gate, but it would be hard luck indeed if he discovered no ladder or other means of scaling the wall. Such was his scheme in outline. He was keenly alive to its faultiness in detail; much, far too much, was left to chance—a slovenliness he had ever recoiled from. He felt that even the possession of the uniform would only give him the shortest time in which to work; and, while he risked the challenge of any casual warder who might detect his unfamiliar face, his ignorance of the way about would inevitably betray him before long. But his case could hardly be more desperate than at present; and, confident that if only he could hide himself in the chapel the first step to freedom would be gained, he lay down to rest in happier mood than had been his for two days past.

At the first stroke of the morning bell Pringle was on his feet, every nerve in tension, his brain thrilling with the one idea. In his morning freshness and vigour, and after a singularly dreamless sleep, all difficulties vanished as he recalled them, and even before the breakfast hour his impatient ear had already imagined the bell for chapel. When it did begin, and long before the warder was anywhere near his cell, Pringle was standing ready with his badge displayed and the little volumes in his hands. The moment the door opened he was over the threshold; he had walked a yard or two on while the keys still rattled at the next cell; the man in front of him appeared to crawl, and the way seemed miles long. In his impatience he had taken a different place in the procession as compared with yesterday, and when at length he reached the haven and made for his old seat at the end of the bench against the wall he was promptly turned into the row in front of it. His first alarm that his plans were at the very outset frustrated gave way to delight as he found himself within a few inches only of the warder's pew without so much as a bench intervening, and, lest his thoughts might be palpable on his face, he feared to look up, but gazed intently on his open book.

The service dragged on and the chaplain's voice sounded drowsier than ever as he intoned the prayers, but the closing hymn was given out at last, and Pringle seized a welcome distraction by singing with a feverish energy which surprised himself. A pause, and then, while the organist resumed the air of the hymn, the prisoners rose, bench after bench, and filed out. The warder had passed from the pew towards the central aisle; he was watching his men out with face averted from Pringle. Now was the supreme moment. As his neighbours rose and turned their backs upon him, Pringle, with a rapid glance around, sidled down into the warder's pew and crouched along the bottom. Deftly as he had slid into the confined space, the manoeuvre was not without incident—his collar burst upon the swelling muscles of his neck, and the stud with fiendish agility bounced to the floor, while quaking he listened to the rattle which should betray him. Seconds as long as minutes, minutes which seemed hours passed, and still the feet tramped endlessly along the floor. But now the organ ceased. Hesitating shuffles told the passing of some decrepit prisoner, last of the band, there was a jingling of keys, some coarse-worded remarks, a laugh, the snapping of a lock, and then—silence. Pringle listened; he could hear nothing but the beating of his own heart. Slowly he raised himself above the edge of the desk and met the gaze of a burly man in a frogged tunic, who watched him with an amused expression upon his large round face. "Lost anything?" inquired the big man with an air of interest.

"Yes, my liberty," Pringle was about to say bitterly, but, checking himself in time, he only replied, "My collar stud."

"Found it?"

For answer Pringle displayed it in his fingers, and then restored the accuracy of his collar and tie.

"Come this way," said the befrogged one, unlocking the door, and Pringle accepted the invitation meekly. Resistance would have been folly, and even had he been able to take his captor unawares, the possible outcome of a struggle with so heavy a man was by no means encouraging.

As the key turned upon Pringle and he found himself once more in the cell which he had left so hopefully but a short half-hour ago, he dropped despondently upon the stool, heedless of the exercise he was losing, incurious when in the course of the morning a youngish man in mufti entered the cell with the inquiry:

"Is your name Stammers?"

"Yes," Pringle wearily replied.

"You came in the night before last. I think? Did you complain of anything then?"

"Oh, no! Neither do I now." Pringle began to feel a little more interested in his visitor, whom he recognised as the doctor who had examined him on his arrival at the prison. "May I ask why you have come to see me?"

"I understand you are reported for a breach of discipline, and I have come to examine and certify you for punishment," was the somewhat officially dry answer.

"Indeed! I am unaware of having done anything particularly outrageous, but I suppose I shall be told?"

‘“Oh, yes; you'll be brought before the governor presently. Let me look at your tongue. . . . Now just undo your waistcoat—and your shirt—a minute. . . . Thanks, that will do."

The doctor’s footsteps had died away along the gallery before Pringle quite realised that he had gone. So this was the result of his failure. He wondered what form the punishment would take. Well, he had tried and failed, and since nothing succeeds like success, so nothing would fail like failure, he supposed.

"Put on yer badge an' come along o' me."

It was the Irish warder speaking a few minutes later, and Pringle followed to his doom. At the end of the gallery they did not go up, as to chapel, nor down to the basement, as for exercise, but down one flight only to a clear space formed by the junction of the various blocks of the prison, which starred in half a dozen radiations to as many points of the compass. As his eye travelled down the series of vistas, with tier above tier of galleries running throughout and here and there a flying cross-bridge, Pringle noted with dismay the uniformed figures at every turn, and the force of his fellow-prisoner’s remark as to the folly of a single-handed attempt to escape was brutally obvious. He was roused by a touch on the shoulder. The Irish warder led him by the arm through an arched doorway along a dark passage, and thence into a large room with "Visiting Magistrates" painted on the door. Although certainly spacious, the greater part of the room was occupied by a species of cage, somewhat similar to that in which Pringle had been penned at the police court. Opening a gate therein the warder motioned him to enter and then drew himself up in stiff military pose at the side. Half-way down the table an elderly gentleman in morning dress, and wearing a closely cropped grey beard, sat reading a number of documents; beside him, the ponderous official who had shared Pringle's adventure in the chapel.

"Is this the man, chief warder?" inquired the gentleman. The chief warder testified to Pringle's identity, and "What is your name?" he continued.

"Give your name to the governor, now!" prompted the Irshman, as Pringle hesitated in renewed forgetfulness of his alias.

"Augustus Stammers, isn't it?" suggested the chief warder impatiently.

"Yes."

"You are remanded, I see," the governor observed, reading from a sheet of blue foolscap, "charged with unlawfully and knowingly uttering a piece of false and counterfeit coin resembling a florin." Pringle bowed, wondering what was coming next. "You are reported to me, Stammers," continued the governor, "for having concealed yourself in the chapel after divine service, apparently with the intention of escaping. The chief warder states that he watched you from the gallery hide yourself in one of the officers' pews. What have you to say?"

"I can only say what I said to the chief warder. My collar stud burst while I was singing, and I lost it for ever so long. When I did find it in the warder's pew the chapel was empty."

"But were you looking for it when you hid yourself so carefully? And why did you wait for the warder to turn his back before you looked in the pew?"

"I only discovered it as we were about to leave the chapel. Even if I had tried to escape, I don't see the logic of reproving a man for obeying a natural instinct."

"I have no time to argue the point," the governor decided, "but I may tell you, if you are unaware of it, that it is an offence, punishable by statute, to escape from lawful custody. The magistrate has remanded you here, and here you must remain until he requires your presence at"—he picked up the foolscap sheet and glanced over it—"at the end of five more days. Your explanation is not altogether satisfactory, and I must caution you as to your future conduct. And let me advise you not to sing quite so loudly in chapel. Take him away."

"Outside!"

Stepping out of the cage Pringle was escorted back to the cell, congratulating himself on the light in which he had managed to present the affair. Still, he felt that his future movements were embarrassed; plausible as was the tale, the governor had made no attempt to conceal his suspicions, and Pringle inclined to think he was the object of a special surveillance when half a dozen times in the course of the afternoon he detected an eye at the spy-hole in the cell door. It was clear that he could do nothing further in his present position. He recalled the advice given him yesterday, and determined to "fetch the farm." There only could he break fresh ground; over there he might think of some new plan—perhaps concert it with another prisoner. Anyhow, he could not be worse off. But here another difficulty arose. He was in good, even robust, health; and the doctor, having overhauled him twice recently, could hardly be imposed upon by any train of symptoms, be they never so harrowing in the recital. Suddenly he recalled a statement from one of those true stories of prison-life, always written by falsely-accused men—the number of innocent people who get sent to prison is really appalling! It was on the extent to which soap-pills have been made to serve the purpose of the malingerer. Now the minute slab upon his shelf had always been repellent in external application, but for inward consumption—he hurriedly averted his gaze! But this was no time for fastidiousness; so, choosing the moment just after one of the periodical inspections of the warder, he hurriedly picked a corner from the stodgy cube, and, rolling it into a bolus, swallowed it with the help of repeated gulps of water. As a natural consequence, his appetite was not increased; and when supper arrived later on he contented himself with just sipping the tea, ignoring the brown loaf.

Sleep was long in coming to him that night; he knew that he was entering upon an almost hopeless enterprise, and his natural anxiety but enhanced the dyspeptic results of the strong alkali. Towards morning he dropped off; but when the bell rang at six there was little need for him to allege any symptoms of the malaise which was obvious in his pallor and his languid disinclination to rise.

"Ye'd better let me putt yer name down for the docthor, Stammers," was the not unkindly observation of the Irish warder as he collected the tins. Pringle merely acquiesced with a nod, and when the chapel bell rang his cell door remained unopened.

"Worrying about anything?" suggested the doctor, as he entered the cell about an hour afterwards.

"Yes, I do feel rather depressed," the patient admitted.

A truthful narrative of the soap disease, amply corroborated by the medical examination, had the utmost effect which Pringle had dared to hope; and when, shortly after the doctor's visit, he was called out of the cell and bidden to leave his badge behind, he was conscious of an exaltation of spirits giving an elasticity to his step which he was careless to conceal.

Along the passage, through a big oaken door, and then by a flight of steps they reached the paved courtyard. Right ahead of them the massive nail-studded gates were just visible through the inner ones which had clanged so dismally in Pringle's ears just three nights back.

"Fair truth, mate, 'ave I got the 'orrors? Tell us strite, d'yer see em?" In a whisper another and tremulous candidate for "the farm" pointed to the images of a pair of heraldic griffins which guarded the door; the sweat stood in great drops upon his face as he regarded the emblems of civic authority, and Pringle endeavoured to assure him of their reality until checked by a stern "Silence there!"

"Turn to the left," commanded the warder, who walked in the rear as with a flock of sheep.

From some distant part of the prison a jumbled score of men and women were trooping towards the gate. They were the friends of prisoners returning to the outside world after the brief daily visit allowed by the regulations, and as their paths converged towards the centre of the yard the free and the captive examined one another with equal interest.

"Ough!" "Pore feller!" "'Old 'im up!" "Git some water, do!" The tremulous man had fallen to the ground with bloated, frothing features, his limbs wrenching and jerking convulsively. For a moment the two groups were intermingled, and then a little knot of four detached itself and staggered across the yard. A visitor, rushing from his place, had compassionately lifted the sufferer from the ground, and, with the warder and two assisting prisoners, disappeared through the hospital entrance. In surly haste the visitors were again marshalled, and a warder beckoned Pringle to a place among them. For a brief second he hesitated. Surely the mistake would be at once discovered. Should he risk the forlorn chance? Was there time? He looked over to the hospital, but the Samaritan had not re-appeared.

"Come on, will yer? Don't stand gaping there!" snarled the warder.

The head of the procession had already reached the inner gate; Pringle ran towards it, and was the last to enter the vestibule. Crash! He was on the right side of the iron gate when it closed this time.

"How many?" demanded the gatekeeper.

"Twenty!" bawled the warder in the yard.

Deliberately the man counted them, and Pringle palpitated like a steam-hammer. Would he never finish? What a swathe of red-tape! At last! The wicket opened, another second——— No, a woman squeezed in front of him; he must not seem too eager. Now! He gave a sob of relief.

In the approach a man holding a bundle of documents was discharging a cab. Pringle was inside it with a bound.

"Law Courts!" he gasped through the trap. "Half a sovereign if you do it quickly!"

A whistle blew shrilly as they passed the carriage gates. Swish—swish! went the whip. How the cab rocked! There was a shout behind. The policeman on point duty walked over from the opposite corner, but as the excited warders met him half-way across the road, the cab was already dwindling in the distance.

THE END.

- ↑ Warders.

This work is in the public domain in the United States because it was published before January 1, 1927.

The author died in 1943, so this work is also in the public domain in countries and areas where the copyright term is the author's life plus 75 years or less. This work may also be in the public domain in countries and areas with longer native copyright terms that apply the rule of the shorter term to foreign works.