10. In General.

Music enters the semi-civilized stage along with the other activities of developing society. When a people emerges from the heedless and irregular habits of savagery, its music usually attracts enough reasoning and skill to make it in some sense artistic. The advance appears in heightened dexterity with song and instruments, in more exactly defined styles of composition, and in some attempt at literature about music, including often the use of a notation. Why some peoples cross this line and others do not is an enigma. However this may be, brief reference must be made to certain past or present systems of this grade, even though our knowledge of them is imperfect and though they seem wholly unconnected with our own music.

Among existing systems, those of China, India and the Mohammedans will be emphasized, and among ancient systems, those of Mesopotamia, the Hebrews and Egypt — the latter being probably rather more than "semi-civilized," though decisive data are lacking.

11. China.

From Chinese literature it appears that music has had a long and honorable hisotry in connection wiht Confucianism and under the patronage of the imperial court. Some of the temple music to-day is impressive, and the tone-system and many instruments are notable. Yet the status of popular music, as heard in the streets and the theatres, is notoriously low. Possibly the present is a time of degeneracy from ancient standards, or perhaps in past times suggestions of progress were so partially assimilated as not to affect general use. It seems as if music, haivng reached a certain point, became fixed, without the power of further advance.

Tradition ascribes the origin of music to diving inspiration, and names the Emperors Fo-Hi (c. 3000 B.C.) and Hoang-Ti (c. 2600 B.C.) as poineers in organization. Confucius (d. 478 B.C.) and his more studious disciples seem to have favored a seirous use of music and acute speculation about it. It is said that actually hundreds of treatises are extant {{section|33} upon the art, the contents of which are but slightly known to us. The details of music at state and religious functions are supervised by an imperial bureau, and degrees in music are given on examination. Yet the popular use of music is limited, being largely in the hands of traveling beggars (often blind).

The tone-system is theoretically complicated. Its basis is probably tetrachordal, like the Greek, but in practice it tends to a pentatonic scale, discarding semitones. But the division of the octave into twelve semitones is also known and in theory is applied somewhat intricately. The rhyths of song are emphatic and almost always duple. Some rudiments of harmony are known, but are rarely used except for tuning.

The tones of the pentatonic series may be roughly represented by our tones f, g, a c, d. They bear fantastic Chinese names — 'Emperor,' 'Prime Minister,' 'Subject People,' State-Affairs,' 'Picture of the Universe.' For each there is a written character, so that melodies can be recorded in a letter-like notation, written vertically. Many melodies have been transcribed by foreign students. Their pentatonic basis gives them a peculiar quaintness, recalling old Scottish songs. In 1809 Weber took one of these as the theme for his overture to Schiller's Turandot, but such adaptations are extremely rare.

One peculiarity of Chinese speech has musical significance. The language consists almost wholly of monosyllables, each of which has different meanings according to the "tone" or melodic inflection with which it is pronounced. It is possible that these "tones," which are four or five in number, have relation to song. At all events, dignified or poetic utterance tends towards chanting or cantillation.

It is interesting that in cases where European music has been introduced by missionaries it has sometimes been adopted with astonishing ease and enthusiasm, extending even to elaborate part-singing.

Chinese instruments are numerous and important. But it is uncertain which of them are indigenous and which are borrowed from other parts of Asia. Native writers say that nature provided eight sound-producing materials — skin, stone, metal, clay, wood, bamboo, silk, gourd — and classify their instruments accordingly.

Thus dressed skin is used in manifold tambourines and drums, with one or two heads, the sizes running up to large tuns mounted on a pedestal. Stone appears in plates of jade or agate, single or in graduated sets, hung by cords from a frame and sounded by a mallet or beater, producing a smooth, sonorous tone. Metal is wrought chiefly into bells, gongs and cymbals of many shapes and sizes (the gongs sometimes arranged in graduated sets), but also into long, slender trumpets. Clay

Fig. 8. — Chinese Moon-Guitar or Yuekin.

Fig. 8. — Chinese Moon-Guitar or Yuekin. Fig. 9. — Chinese Ur-heen or Japanese Kokiu — the bowstring passes between the strings.

Fig. 9. — Chinese Ur-heen or Japanese Kokiu — the bowstring passes between the strings.

furnishes whistles of the ocarina type, often molded into fantastic animal shapes. Wood, besides forming the bodies of stringed instruments, is made into clappers or castanets, into curious boxes that are sounded by striking, and into coarse oboes (usually with metal bells and other fittings). Bamboo provides the tubes of both direct and transverse flutes, with 6-9 finger-holes, and for syrinxes and the "cheng" (see below). Silk furnishes the strings for zithers (as the "che," with 25 strings, and the "kin," with 7), lutes (as the "moon-guitar," with 4 strings, the "pipa," also with 4, and the "san-heen," with 3), viols or fiddles (as the "ur-heen," with 2 strings, and the "hu-kin," with 4), and bow-zithers (as the "la-kin," with 20 strings). [Several other instruments are strung with wire, as the "yang-kin," or dulcimer and the"tseng" or bow-zither, both with 20 strings.] A gourd makes the resonance-bowl of the "cheng," having also some 13 or more little bamboo pipes, each of which contains a minute free reed of brass.

Bell-founding is supposed to have been acquired by Europe from China, and the "cheng" is the prototype of several free-reed instuments in Europe invented since 1800, including the accordion and the reed-organ.

Fig. 11. — Chinese Temple Gong, elaborately damascened.

Fig. 11. — Chinese Temple Gong, elaborately damascened.

The Japanese musical system was derived from China, but so long ago that it has now become distinct. The popular use of singing and of instruments is here an almost universal accomplishment of importance, but, on the other hand, the literary treatment of the art is meagre.

For a time, from 1878, the Japanese government sought to establish American methods of singing in the public schools, and through foreign intercourse generally the national system is being much modified.

Japanese instruments are in general replicates of the Chinese, but with many variations of detail and usually with greater external beauty.

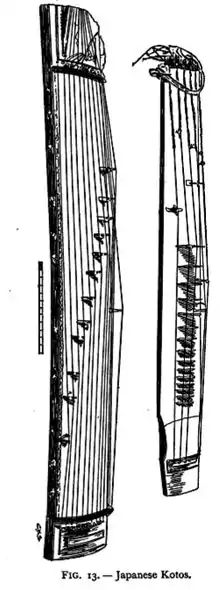

Notable types are the "koto," a large zither with 6-13 silk strings, and the "samisen," a lute with 3 strings. The "kokiu" correspons to the Chinese "ur-heen," the "biwa" to the "pipa," the "hyokin" to the "yang-kin," the "sho" to the "cheng," etc.

12. India.

The details of Hindu music are better known than those of Chinese. Evidently from the time of the Aryan immigrations (c. 2000 B.C.) much attention has been paid to the art. But, since India has been repeatedly invaded and even subjugated by foreign people, and has been for ages in close commercial relation with Western countries, no one can say what of its music is original.

Native legends attribute the gift of music to the gods, and mythical and mystical notions are frequent in musical nomenclature and writing. References to music abound in the old literature, and musical treatises have been accumulating for centuries. Theorizing about music has run to incredible intricacies.

Music exists chiefly in the form of popular song or as an accompaniment for dancing. In religious ceremony it is less frequent, though somewhat used by both Brahmins and Buddhists. The singing of poems is universal, from the old Sanscrit odes to the ballads of modern origin. Dancing to music is very popular, and professional dancing-girls are a feature at social functions. Music is often employed in pantomimes and plays having a mythical, social or fantastic subject.

The training of the Bayaderes or w:Nautch girls is usually managed as a business by Buddhist priests, and is often associated with immorality.

The tone-system rests upon a primary division of the octave into seven steps, but more exactly into twenty-two nearly equal "srutis" or quarter-steps. These latter are not all used in any single scale, but serve to define with precision various seven-tone scales that differ in the location of the shorter steps (as in the mediæval modes of Europe). Theory has been so refined as to name almost 1000 possible varieties of scale (not to mention the 16,000 of mythical story). In practice not more than twenty of these appear, the usage varying with locality and tribe. Most of these scales are somewhat akin to ours, so that melodies in them often suggest our common modes. But the intonation is usually obscured by plentiful melodic decorations. many songs are pleasing and expressive to Occidental taste, the ancient ones having much dignity, but popular singing often runs off into weird and curious effects, probably due to Mohammedan influence.

Triple rhythms are at least as common as duple. The metric schemes are apt to be varied and complicated, corresponding to those of poetry Variations in pace and accent are frequent. Both eht pitch and duration of tones, with various points about execution, are indicated by a notation of Sanscrit characters for notes, and signs or words for other details.

The art of making instruments has been as minutely studied as the theory of scales. Almost every species of portable instrument is known, and in many varieties. Native writers indicate four classes — those with strings, those with membranes sounded by striking, those strick together in pairs, and those sounded by blowing. Of these the stringed group is by far the most characteristic and admired. Percussives include various drums, tambourines, castanets, cymbals, gongs, etc. Wind instruments include many flutes (though not often of the transverse kind), oboes, bagpipes, horns and trumpets.