- Part I

Uncivilized and Ancient Music

- Chap. I. Primitive or Savage Music.

- 5. In General.

- 6. As a Social Institution.

- 7. Its Technical Features.

- 8. Instruments.

- 9. The Origin of Music.

- Chap. II. Semi-Civilized Music.

- 10. In General.

- 11. China.

- 12. India.

- 13. The Mohammedans.

- 14. Babylonia and Assyria

- 15. Israel.

- 16. Egypt.

- Chap. III. Greek and Roman Music.

- 17. In General.

- 18. Union of Music with Poetry.

- 19. Actual Effects.

- 20. Acoustical and Theoretical Research.

- 21. Notation.

- 22. Roman Music.

- 23. Literature about Music.

Chapter I: Primitive or Savage Music

5. In General

Some form of music is found in every part of the uncivilized world, from the islands of the southern Pacific round to the Americas, and from the equatorial zone far toward the poles. This extensive diffusion points to a spontaneous use by all races of song, dance and instrument as a means of expression, amusement and even discipline. The primary impulse to music seems to belong to mankind as a whole.

Although most savage music is crude and to us disagreeable, yet its interest for the student is considerable. By noting how it arises, how it is used, and with what is is associated, we gain insight into the essence and relations of the musical impulse. The widespread combination of song with dancing, mimicry and poetry, as well as with religious exercises, challenges attention. The painstaking care in fashioning instruments is impressive and instructive. The naïve experiments in scale-making suggest the probable sources of modern theory. The analogies between the musical efforts of primitive adults and those of civilized children have a bearing upon current pedagogy. For the critical student of either history or æsthetics, therefore, the facts of savage music are valuable.

The great difficulty of the topic lies in the variable accuracy and clearness of the first-hand reports of the facts that come from travelers, missionaries and other observers.

6. As a Social Institution

In primitive conditions music is first of all a social diversion or play, affording an outlet for surplus animal spirit, stimulating emotional excitement, and helping to maintain muscular and nervous energy. Singing and dancing are always conspicuously social—a center of interest for perhaps a whole village or tribe. The craving for popular activity in these ways often leads to stated gatherings of a festal character, the ceremonies usually being specifically associated with an occupation or event, as with hunting, agriculture, worship or war, or with birth, sickness or death. The psychical reactions of motions in rhythm and of tones are far more striking than among civilized peoples, and are sought both for their effect on the individual performer or percipient and for their mesmeric control of the crowd.

The practice of music is sometimes shared by men and women alike, but sometimes, for obscure reasons, is reserved to one or the other sex exclusively. Sometimes there is a musical class or guild that superintends musical exercises and maintains traditions. Often music is held to be more or less of a superhuman mystery—a notion duly utilized by the priest and the necromancer.

Among savage peoples music seldom appears as an independent art. Its association with dancing is so close that the two are really twin activities. Rhythmic motions with some recurrent noise, like hand-clapping or the striking of sticks, pass over readily into a rude chant or singsong, perhaps aided by some instrumental accessory. Conversely, the rhythm of singing tends to induce bodily motions. Rhythm thus inevitably brings dancing and song together.

Again, since speaking and singing are both vocal processes, they tend to react upon each other. All primitive speech that is highly emotional or meant to be specially impressive is cast in forms of poetry. To conceive such utterance with reference to singing, and actually to chant it, seems instinctive. Where there is a guild of tribal minstrels, they are expected to provide odes or ballads of various sorts—heroic, martial, mythical, fanciful or humorous. In form such odes are usually rhythmic, but true recitative or cantillation is not uncommon.

In some cases the text has an evident charm or pathos, but in others it seems devoid of sense or sentiment. Instances occur of the use of mere nonsense-jingles and of even a song-jargon, quite distinct from ordinary speech—thus testifying to an interest in the rhythmic or tonal effect apart from the thought.

Finally, since mimicry or pantomime is instinctively sought by all races, dancing and song readily assume a dramatic character, involving personification, plot and action. The story may be serious or comic, exciting or diverting, strenuous or enervating, but, whatever its character, the effect is likely to be heightened by musical or or orchestral treatment. Religious exercises are frequently cast int he form of such song-pantomimes. Indeed, it seems as if primitive religion felt itself forced to adopt musico-dramatic modes of expression.

7. Its Technical Features.

All savage music is conspicuously accentual. Usually the accents fall into definite rhythms, duple varieties being commoner than triple. The basal rhythm is made emphatic by bodily motions, noises or vocal cries. The metric patterns (schemes of long and short tones) and the larger phrase-schemes are often curiously intricate, puzzling even the trained observer.

In accompanied songs there are instances of duple patterns in the voice against triple ones in the accompaniment.

The vocal decoration of rhythms leads directly to melodic figures, though the latter doubtless also result from experiments with instruments. As a rule, a given melody contains but few distinct tones, though sometimes varied with indescribable slides or howls. One or two tone-figures are usually repeated again and again. Generally a rudimentary notion of a scale (or system of tones) is suggested, though no one type of scale is universal. Scales and the melodies made from them are more often conceived downward than upward (as is our habit). Whether a true keynote is recognized is often doubtful, the whole intonation being vague and fluctuating. The total effect is generally minor, though major intervals and groups of tones are not unusual.

On the one hand, cases occur in which short intervals, like the semitone, are avoided, yielding melodies that imply a pentatonic system, and these are common enough to lead many to urge that the essentially primitive scale is pentatonic. But, on the other, what we call chromatic scales are also found, utilizing even smaller intervals than the semitone. Scales approximating our diatonic type are also reported, implying a fair sense of tone-relationship.

Just what stimulates the invention of melodies and controls their development is uncertain. In some cases the habit of improvisation seems influential; in others, ingenuity with instruments. A form of melody, once established, is apt to be tenaciously preserved.

It has been thought that ideas of harmony or part-singing are impossible for the savage mind. But it appears that some tribes in Africa and Australia do sing in parts and even attempt concerted effects between voices and instruments. Such combinations, however, are rare and do not show any real system.

Fig. 1. — Alaskan Stone Flute — design like a totem-pole.

Fig. 1. — Alaskan Stone Flute — design like a totem-pole. Fig. 2. — Arab Pan's-Pipes or Syrinx.

Fig. 2. — Arab Pan's-Pipes or Syrinx. Fig. 3. — African Zanzes — iron or bamboo tongues mounted on a resonance-box, played by twanging.

Fig. 3. — African Zanzes — iron or bamboo tongues mounted on a resonance-box, played by twanging. Fig. 4 — Miscellaneous Drums - primitive, Egyptian, Turkish, Japanes, etc., one (Thibetan) made of a skull cut in two.

Fig. 4 — Miscellaneous Drums - primitive, Egyptian, Turkish, Japanes, etc., one (Thibetan) made of a skull cut in two. Fig. 5. — African Marimba or Xylophone.

Fig. 5. — African Marimba or Xylophone.

8. Instruments.

This branch of the topic is made specially clear and interesting by the existence of many actual specimens in all large ethnological museums. Yet a systematic summary of the facts in any brief form is impossible, since the details vary indefinitely.

Extraordinary cleverness and genuine artistic feeling are often displayed in fashioning musical implements by peoples otherwise very rude. Great patience and dexterity are expended in working such materials as are available into the desired condition and form, and elaborate carving or tasteful coloring is often added. Well-made instruments are held to be precious, sometimes sacred.

The following summary is designed simply to give a hint of the indefinite variety of forms under three standard classes: —

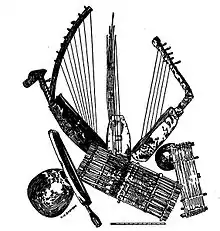

Flatile or wind instruments. — The different flutes and flageolets found are innumerable. They are made from reeds, grasses, wood, bone (even human bones), clay, stone. They are blown across a mouth-hole or through a whistle-mouthpiece, and either by the mouth or by the nose. They are both single and double, or, in the case of syrinxes or Pan's-pipes, compound. Often they are fitted with from two to several finger-holes for varying the pitch, though, curiously, all these are not always habitually used. Occasionally a reservoir for the air is provided, such as a flexible bag or sck, with the pipe or pipes attached. The tones vary greatly in power and sweetness, though the tendency is toward shrill and piercing qualities.

Horns and trumpets are also common, of every shape, size and quality, made of horn, shell, ivory, bamboo, wood, metal. Generally there is little variation of pitch, though overtones are used somewhat. The tones produced are usually powerful, often harsh.

Percussive or pulsatile instruments. — Clappers of bone or wood are frequent, and various hollowed tubes and the like that can be beaten. Castanets of shell or metal are often found. Everywhere rattles and jingles abound, made of bunches of pebbles, fruit-stones or shells (occasionally of a human skull filled with loose objects). All sorts of gongs or tam-tams occur, made of wood, stone, brass, copper, iron; these sometimes appear in sets, so that rude melodies or harmonies are possible. The varieties of drum and tambourine are endless, all characterized by a stretched head of skin over a hollow bowl or box, the latter being usually a gourd, a hollowed piece of wood (as the trunk of a tree) or a metallic vessel. They are sounded either by the hand or by sticks. Much ingenuity is sometimes shown in devising signals and intricate tattoos, and drums are often used in combination.

A specially interesting invention is the African "marimba" or gourd-piano. This consists of a graduated series of gourds surmounted by resonant pieces of wood that can be struck by sticks, like the modern xylophone or glass-harmonicon. Similar forms occur in Asia and elsewhere.

Stringed instruments. — The bow being one of the first implements of hunting and warfare, it may have been among the earliest of musical instruments. Certain it is that rude harps shaped like a bow occurred frequently among savages. The number of strings varies from one or two upward, though the weakness of the framework usually limits both number and tension. Experiments are frequent with rude lyres or zithers having strings stretched over a resonance-body, such as a flat piece of wood or a hollow box. These types pass over into rudimentary lutes, having both a resonance-box and a neck to extend the strings. Much ingenuity is shown in making the strings out of plant-fibers, hair other animal tissues, metal. Many examples are found of instruments sounded by the friction of a bowstring, prefiguring the great family of viols.

Fig. 6 — Primitive Harps and Zithers, strung with plant-fibres, gut or bamboo-strips, and with various devices for resonance.Occasionally pieces of wood or metal of different sizes are so fastened to a resonance-box that they can be sounded by snapping, as in the African "zanze".

Apparently the impulse to instrument-making arises largely from the desire for a sound to accentuate a dance-rhythm — clappers, whistles, twanged strings. In prehistoric remains some bone whistles occur, and everywhere pipes abound.

Hence it has been urged that flatile instruments were the earliest. Another theory is that the order of invention was drums, pipes, strings. It is better to say that instruments were first used to keep time, then to produce sustained tones, then to make melodies. The precise way in which these results were secured probably varied with the materials at hand and the ingenuity at work.

9. The Origin of Music.

After noting facts like these we naturally ask how music came into existence. It is true that external nature supplies suggestions, as in the sighing and whistling of the wind, the rippling and roar of falling water, the cries of beasts, the buzzing or calls of insects and the songs of birds; but the influence of these on primitive song is apparently slight. Herbert Spencer argued that song is primarily a form of speech, arising from the reflex action of the vocal organs under stress of emotion (as a cry follows the sensation of pain). More likely is the hypothesis that music is derived from some attempt to work off surplus energy through bodily motions, to coordinate and decorate which rhythmic sounds, vocal or mechanical, are employed, and that what was at first only an accessory to dancing was finally differentiated from it. But these speculations are not specially fruitful.

The traditions of many races recount the impartation of instruments or of musical ideas to men by the gods. These myths are significant, not as historic statements of fact, but as testimonies to the strange potency and charm residing in musical tones.