.jpg.webp)

JOHN NYREN

From a copy, made by Francis Grehan in 1844, of a drawing from life by Edward Novello

JOHN NYREN

By the Editor

It is due in great part to John Nyren's humility, which places him in his book a little lower than any of the good fellows who batted and bowled for the old Hambledon Club, that the erroneous impression is abroad that the author of the noble pages of The Cricketers of My Time was an illiterate rustic, incapable of writing his own memories.

I do not suggest that every one is so mistaken; but too many people who have read or have heard of Nyren seem to entertain this view. Again and again in conversation I have had to try to put the matter right, although it needs but a little thought to realize that only very fine qualities of head and heart—only a very rare and true gentlemanliness—could have produced the record of such notable worth and independence and sterling character as shine in that book. Good literature is no accident; before it can be, whether it is the result of conversations or penmanship, there must have been the needful qualities, as surely as the egg precedes the chicken. I do not mean that it is not in the power of an illiterate rustic to talk greatly; but it is not in the power of one who remains an illiterate rustic to talk such great talk as The Cricketers of My Time.

A fortunate error in an article on John Nyren, which I wrote five years ago, brought me acquainted with Miss Mary Nyren and her sisters—John Nyren's daughters—now living at Folkestone; and Miss Nyren was so good as to write out for me a little paper of memories of her grandfather, collected from various family sources, which carry the story of his life a little farther than Mr. J. W. Allen's excellent memoir in the Dictionary of National Biography. In Miss Nyren's notes, as well as in that article, John Nyren—to whom cricket was, as it ought to be, only a recreation stands forth a Roman Catholic gentleman of cultivated tastes, a good musician, a natural philanthropist, and the friend of very intelligent men, among them Charles Lamb's friends Leigh Hunt, Cowden Clarke, and Vincent Novello. These things were always known to the few; they ought to be known also to the many.

Part of the misunderstanding has been due to the description of Richard Nyren, his father, as the Hambledon 'ground-man' and the landlord of the now very squalid neighbouring inn called the 'Bat and Ball'. The story, whether true or not, began with Mr. Haygarth, who wrote thus: 'Richard Nyren, whose name appears first in this match, had played at cricket several seasons previously, being now about thirty-seven years of age. All his earliest, and most probably his best, performances are therefore lost. At first he kept the "Bat and Ball Inn", near Broad-Halfpenny Down, at Hambledon; but afterwards the "George Inn" in that village. He looked after the two famous cricket grounds there namely, Broad-Halfpenny and Windmill Downs, and also had a small farm near. During the great matches he always had a refreshment booth on the ground, and his advertisements, requesting the assistance and patronage of his friends, will be found in the Hampshire Chronicle of the last century. Though active, he was a very stout man for a cricketer, being about 5ft. 9in. in height; and he devoted much time to hunting, shooting, and fishing.

'The compiler of this notice was informed (by his maternal grandson) that Richard Nyren was born at, , in 1734 or 1735, and died at Lee, or Leigh, in Kent, April 25, 1797. On searching the registers of burials, however, of the two villages of that name in the county, the name of Nyren could not be found.'

Miss Nyren has no record that her great-grandfather ever kept an inn at all. He was, she tells me, a farmer, and his interest in the state of the ground was that of an ardent cricketer. Possibly, she suggests, another Richard Nyren (there was another—John Nyren's brother) kept the inn. The point seems to me unimportant. The important thing is that our Richard Nyren, whether he was an innkeeper, or a farmer, or both, was a gentleman. Personally I have always liked to think of him as the purveyor of the stingo which his son has made immortal.

To John Nyren's description of his father (on pp. 44—45), Miss Nyren adds 'Richard Nyren was the son or grandson of Lord Nairne, a Jacobite rebel, one of the five lords imprisoned in the Tower and condemned to be beheaded in 1715; he was pardoned, but in 1745 again risked his life, and to save it hid in the New Forest, near Broad-Halfpenny. He transposed the letters in Neyrne (the old spelling of the name) into Nyren, dropping one "e". The title was taken up by a junior branch of the family. When my grandfather, John Nyren, met the Lord Nairne of that time at the Marylebone cricket ground they conversed together, and Lord Nairne took a seal off his watch-chain, with the family crest on it, and gave it to him, and took in exchange John Nyren's, which bore the same crest'.

A few words must be interpolated here, as Miss Nyren's account of her great-grandfather's parentage is a little too free. A comparison of the date of Lord Nairne's death, 1724, and Richard Nyren's birth, 1734 or 1735, shows that another father must be found for the Hampshire yeoman. Lord Nairne (this was the second Lord Nairne, Lord William Murray, fourth son of the Marquis of Atholl, who married Lady Nairne and took her title), as I have said, died in 1724. It was his son, the third Lord Nairne, who was out in the '45, and here again the cold facts of history are too much for us, for after the catastrophe of the Act of Attainder he settled in France, and not in Hampshire; and at that date Richard Nyren was already twelve years old. Richard Nyren may have been a Nairne, but, if so, it was through another branch of the family. The third Lord Nairne (a lord only among Jacobites) died in France in 1770: it was his grandson William (to whom the title was restored, mainly through the efforts of Sir Walter Scott, in 1824) that exchanged rings with our John Nyren.

I now return to Miss Nyren's narrative:—'Richard Nyren married, at Slindon, in Sussex, Frances Pennicud, a young lady of Quaker origin, a friend of the Countess of Newburgh, who gave her a large prayer-book, in which the names of her children were afterwards inscribed. When she was an old lady, still living at Hambledon, she dressed in a soft, black silk dress, with a large Leghorn hat tied on with a black lace scarf, and used a gold-headed cane when out walking. She went out only to church and on errands of mercy. . . . Mrs. Nyren, when a widow, found a happy home in her son John Nyren's house till her death at over ninety years of age. It is said she blushed like a young girl up to that time.'

Richard Nyren, as we have seen, learned his cricket from his uncle, Richard Newland, of Slindon, near Arundel, in Sussex. But of his Slindon performances nothing, I think, is known. It was not until he moved to Hambledon, and helped to found, or joined, the Hambledon Club (the parent of first-class cricket), that we begin to follow his movements. I say 'helped to found', but the club probably had an existence before Nyren joined it. In 1764, in the report of a match between Hambledon and Chertsey, the side is referred to as ' Hambledon, in Hants, called Squire Lamb's Club'. We get an approximate date of the Club's inception from the age of John Nyren's hero, John Small, one of its fathers, who was born in 1737. Let us suppose that when Small was eighteen he threw himself into the project—in 1755, or thereabouts. A fire at Lord's, in 1825—the year in which the Hambledon Club was finally broken up unhappily destroyed all the records of these early days. Richard Nyren's name appears first in Lillywhite's Cricket Scores and Biographies in a single-wicket match in 1771, between Five of the Hambledon Club and Five (i.e., four) of Kent, with Minshull. This was the score:

| Five of Hambledon | Five of West Kent | ||||

| John Small, Senr. | 4 | 6 | J. Boorman | 0 | 2 |

| Thomas Sueer | 1 | 0 | Richard May | 1 | 7 |

| George Leer | 1 | 7 | Minshul | 26 | 11 |

| Thomas Brett | 0 | 4 | Joseph Miller | 0 | 2 |

| Richard Nyren | 5 | 29 | John Frame | 8 | 1* |

| —— 11 |

—— 46 |

* Not out. |

—— 35 |

—— 23 | |

John Nyren was born at Hambledon on December 15, 1764. His education, says his granddaughter, was desultory, largely owing to the difficulties then inseparable from his religion. We must suppose that as a boy he helped his father in various ways on his farm. He joined the Hambledon Club in 1778, when he was fourteen, as 'a farmer's pony'; he stood by it until 1791, when his father moved to London and the great days were over. Only a few reports of the matches remain, owing to the fire of which I have spoken. Lillywhite, in the Cricket Scores and Biographies, gives in the great Richard-Nyrenic period but four in which John Nyren's name appears (and in two of these the name may be that of Richard, and not John). The first of them was in June, 1787, on the Vine at Sevenoaks (where I watch good matches every summer), between the Hambledon Club (with Lumpy) and Kent. Kent won by four wickets, and Nyren (J. or R.) made 10 and 2. Noah Mann was run out, 0, in both innings—the impetuous gipsy! Tom Walker made 43 and 1 0, and H. Walker 39 and 24. In July, on Perriam Downs, near Luggershall, in Wiltshire, Nyren (J. or R.) played for Mr. Assheton Smith against the Earl of Winchelsea, and made 2 and 2. For the Earl, Beldham made 30 and 22, and David Harris took ten wickets, including Nyren's. In the match England v. Hambledon, on Windmill Down, in September, 1787, J. Nyren (J. this time) made 3 and 1; and for Hampshire against Surrey, at Moulsey Hurst, in June, 1788, he made 3 and 9, and was bowled by Lumpy both times.

And here the name drops out of Lillywhite until 1801, when John was thirty-six and established in London in business. Thenceforward it occurs many times in important matches, until his last match in 1817. To these games I come later, merely remarking here that Nyren's new club was the Homerton Club, then the most famous next to the M.C.C. About 1812 it moved from Homerton to the new Lord's ground, amalgamating with the St. John's Wood Club, and afterwards with the M.C.C. itself.

John Nyren married in 1791, the year of Richard Nyren's departure from Hambledon. His bride, Miss Nyren writes, was 'Cleopha Copp, a wealthy girl not quite seventeen, of German parentage, highly educated, and wonderfully energetic. Three days after the birth of her first child, at Portsea, she got up and went downstairs to interpret for some French priests who had emigrated from France owing to the Revolution there being no one else who could speak to them in French. Her mother, Mrs. Copp, was a pioneer of work in the East End of London; she took a large house at West Ham at her own expense, and gave fifty young French female refugees employment in lace making, chiefly tambour work; employing a Jesuit priest to give them instruction two or three times a week.'

Until 1796 John Nyren, whose wife had provided him with a competency, lived at Portsea; in that year he moved to Bromley, in Middlesex; later to Battersea; then to Chelsea, where he had a house in Cheyne Walk; and finally to Bromley again, where he died.

Before introducing the more personal part of Miss Nyren's memoir of her grandfather, I think it would be well to dispose of John Nyren's record as a cricketer, a topic of which too little is known. I have been carefully through Lillywhite, with the result that I find Nyren in thirty matches, of the most noteworthy of which I append particulars. No doubt he played also much in minor contests. This is the first that Lillywhite gives in Nyren's London period:

| On Aram's New Ground, on June 30, 1801. For Montpelier v. Homerton. | ||||

| John Nyren b Walpole | 36 | b | Warren | 10 |

Others follow:— | ||||

| At Lord's, July 23 and 24, 1801. For Homerton v. M.C.C. | ||||

| John Nyren b Turner | 0 | c | Martin | 49 |

On Aram's New Ground, on July 6, 1802. For Montpelier Club v. Homerton. | ||||

| John Nyren b Fulljames | 66 | st | Vigne | 4 |

| (Nyren also bowled White, Esq.) | ||||

At Lord's, on August 25, 1802. For England v. Surrey. | ||||

| John Nyren b T. Walker | 0 | c | H. Walker | 30 |

At Lord's, September 13, 14, 15, and 16, 1802. For Twenty-two of Middlesex v. Twenty-two of Surrey. | ||||

| J. Nyren st Caesar | 11 | c | Lawrell | 2 |

| (Nyren also caught three and stumped two). | ||||

At Lord's, June 6, 7, 8, 9, and 10, 1803. For Twenty-two of Middlesex v. Twenty-two of Surrey. | ||||

| J. Nyren b Collins | 10 | c | T. Howard | 1 |

| (Nyren also caught out six.) | ||||

At lord's, May 28, 29, and 30, 1804. For Homerton (with Beldham) v. M.C.C. | ||||

| John Nyren st Leicester | 6 | b | Cumberland | 44 |

| (Beldham made 13 and 48, and Homerton won. Nyren had the pluck to catch Lord Frederick Beauclerk, who made 87.) | ||||

At Homerton, June 8 and 9, 1804. For Homerton (with Beldham) v. M.C.C. | ||||

| J. Nyren b Beauclerk | 23 | st | Smith | 40 |

At Lord's, July 16, 17, and 18, 1804. For Homerton (with Lord F. Beauclerk) v. Middlesex. | ||||

| J. Nyren b Beeston | 31 | b | Beeston | 32 |

At Richmond Green, August 21 and 22, 1805. For Homerton (with Beldham) v. Richmond (with Lord F. Beauclerk). | ||||

| J. Nyren c Long | 49 | runout | 4 | |

At Lord's, June 23, 1806. For Homerton (with Beldham and Lambert) v. M.C.C. | ||||

| J. Nyren c Smith | 0 | c | Lennox | 29 |

| (The M.C.C. won by 27. Lambert made 75 and 17, Beldhara 32 and 40. Nyren again caught Lord Frederick Beauclerk, after he had made 49. | ||||

At Lord's, June 25, 26, and 27, 1807. For Homerton v. M.C.C. | ||||

| J. Nyren c Leicester | 13 | absent | 0 | |

| (Nyren bowled three and caught one.) | ||||

At Lord's, June 6 and 7, 1808. For Homerton (with Small, Lambert, Hammond, and Bennett) v. M.C.C. (with Beldham, Robinson, and Walker). | ||||

| J. Nyren c Bligh | 1 | absent | 0 | |

| (The M.C.C. won. Lord Frederick Beauclerk for M.C.C. made 100 and 51. Nyren caught two.) | ||||

At Woodford Wells, in Essex, July 14, 15, and 16, 1808—thirteen a side. For Homerton (with T. Mellish, Lambert, Hammond, and Walker) v. Essex (with Lord F. Beauclerk, Aislabie, Burrell, Pontifex, and Beldham). | ||||

| J. Nyren b Beauclerk | 24 | c | Beldham | 10 |

| (Nyren caught four.) | ||||

Too soon we come to Nyren's last important match, when he was in his fifty-third year. I regret to say that he did not trouble the scorers. He played for Lord Frederick Beauclerk' s side against Mr. William Ward's side, at Lord's, June 18, 19, and 20, 1817. Thumwood bowled him. For Mr. Ward (to whom Nyren dedicated his book) Lambert made 78 and 30, and Beldham 4 and 43. Lord Frederick made 28 and 37, and Mr. Osbaldeston 10 and 39 not out. Lord Frederick won by six wickets.

To the score of this match Mr. Haygarth appends an account of Nyren: 'He was an enthusiastic admirer of the "Noble Game" ("his chivalry was cricket"), and about 1833, published the "[Young] Cricketer's Guide [Tutor]", a book which contains an account of the once far-famed Hambledon Club, in Hampshire, when it was in its prime and able to contend against All England. Had not this book (which, however, is sadly wanting in dates, especially as to the formation and dissolution of the club, etc.) appeared, but little would now be known of those famous villagers.

'Nyren was left-handed, both as a batsman and field, and played in a few of the great matches at Lord's after leaving his native village, being for several seasons a member of the Homerton Club. Considering, however, that he continued the game till he was past sixty, his name will but seldom be found in these pages. It does not appear at all from 1788 to 1801, or from 1808 up to the present match. He was a very fine field at point or middle wicket, was 6ft. high, being big-boned, and of large proportions.'

Among the very few persons now living that remember John Nyren is Canon Benham, who as a boy once met him. Canon Benham tells me that a story illustrating Nyren's judgement in the field used to be told, in which that player calculated so accurately the fall of a ball hit high over his head that, instead of running backwards to it in the ordinary way, keeping his eye on it all the time, he ran forwards and then turned at the right moment and caught it. Canon Benham also recalls a great story of a Hambledon match at Southsea. When the time came for Hambledon's second innings, six runs only were wanted. The first ball, therefore, the batsman—whose name, I regret, is lost—hit clean out of the ground into the sea, and the match was won. Canon Benham can remember the striker's tones as he corroborated the incident: 'Yes, I sent hurr to say.'

I now resume Miss Nyren's narrative: 'My grandfather was enthusiastic about cricket and all that concerned it to the last day of his life, but only as a pastime and recreation, not as an occupation, as writers of the day would make out. I will quote en passant a passage written by his eldest son, Henry. "My father, John Nyren, was known to the cricketers of his time at the Marylebone Club as 'young Hambledon'. He was a constant player of that manly game, and excelled in all its points, generally carrying out his bat, often keeping the bat two whole days, and once three. [This would be, I assume, in minor matches.] When fielding, by the quickness of his smart, deep-set eyes, he would catch out at the point; this was his favourite feat, and his fingers carried the marks of it to his grave. With some batters one might as soon catch a cannon-ball."

'My grandfather could use his left hand as dexterously as his right. He was a good musician, and a clever performer on the violin, an intimate friend of Vincent Novello's, and a constant attendant at the celebrated "Sunday Evenings" at his house. There he met Charles Lamb, Leigh Hunt, Cowden Clarke, Malibran, and other celebrities. He often took with him his youngest son, John William Nyren, my father, then a lad, who in later years often told me and my sisters how he enjoyed listening to the witty conversation and the good music which always formed part of the entertainment.'

That Nyren loved music is very clear to the reader of The Cricketers of My Time. He says, it will be remembered, of Lear and Sueter's glees at the 'Bat and Ball', on Broad-Halfpenny:—

I have been there, and still would go;

'Twas like a little heaven below.

It is interesting to note that Charles Lamb uses the same quotation from Dr. Watts in his account of the musical evenings at Novello's.

Both Leigh Hunt and Cowden Clarke, as we shall see, have written of their friend; but I cannot find any reference to him in the writings of Charles Lamb. I wish I could, for Lamb, although he would have cared even less for cricket than for music, would have been one of the first to detect the excellences of Nyren' s book, especially such passages as the robustly lyrical praise of ale, and the simple yet almost Homeric testimony to the virtues of the old players and celebration of their unflinching independence.

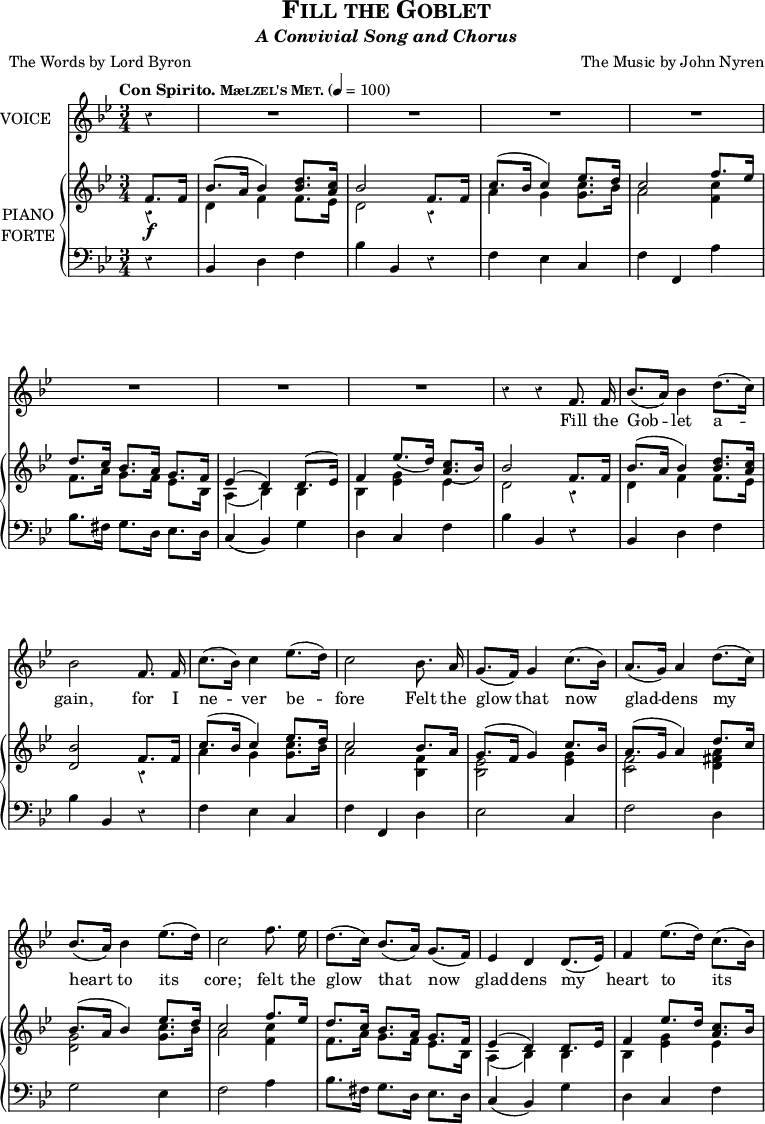

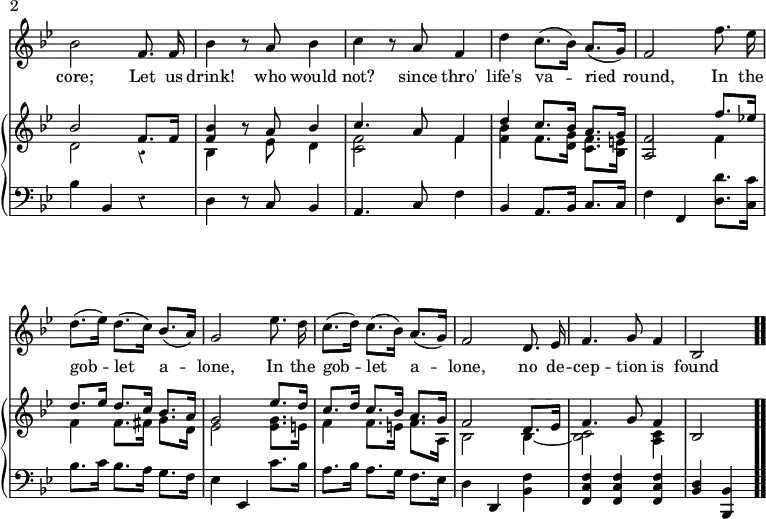

Miss Nyren continues: ' My grandfather was very fond of all children, and much beloved by all Vincent Novello's family: they called him "Papa Nyren". One of the daughters, the late Mary Sabilla Novello, wrote as recently as 1903, that she well remembered him when she was very young, as being "very kind and indulgent to little children, always ready to join heartily in all their merriments". We still have heaps of music inscribed to him by Vincent Novello, with all kinds of playful and affectionate words. It was my grandfather who first remarked the beauty of Clara Novello's voice, and advised her father to have it carefully trained. He composed three pieces of music which Novello published, two of which were "Ave Verum" and the accompaniment to Byron's spirited song "Fill the Goblet again"; I do not know what the third was.' I give a reproduction of the drinking song from Miss Nyren's copy.

3

![\version "2.18.2"

#(set-global-staff-size 17)

\header { tagline = ##f }

\layout { indent = #0 }

\new Score { <<

\new Staff \relative f'' { \key bes \major \time 3/4 \partial 4 \override Score.TimeSignature #'stencil = ##f \override Score.Rest.style = #'classical \override Score.BarNumber #'break-visibility = #'#(#f #f #f) \mark \markup \bold "CHORUS." \autoBeamOff

f8.^\f ees16 | d8.[( ees16)] d8.[( c16)] bes8.[( a16)] |

g2 ees'8. d16 | c8.[( d16)] c8.[( bes16)] a8.[( g16)] |

f2 d8. ees16 | f4. g8 f4 bes,2 r4 | R2.*3 r4 r }

\addlyrics { In the gob -- let a -- lone, In the gob -- let a -- lone, No de -- cep -- tion is found. }

\new Staff \relative bes' { \key bes \major \clef alto \autoBeamOff

bes8.^\f a16 | bes8.[( a16)] bes8.[( fis16)] g8.[( d16)] |

ees2 g8. e16 | f4 f8.[( e16)] f8.[( g16)] | bes,2 bes8. bes16 |

c4. c8 c4 | bes2 r4 | R2.*3 r4 r }

\addlyrics { In the gob -- let a -- lone, In the gob -- let a -- lone, No de -- cep -- tion is found. }

\new Staff \relative f' { \clef tenor \key bes \major \autoBeamOff

f8.^\f f16 | f4 f8.[( d16)] d8.[( f16)] | bes,2 c8. g16 |

c8.[( bes16)] c4 c8.[( a16)] | bes2 f8. bes16 | bes4. bes8 a4 |

bes2 r4 | R2.*3 r4 r }

\addlyrics { In the gob -- let a -- lone, In the gob -- let a -- lone, No de -- cep -- tion is found. }

\new Staff \relative d' { \clef bass \key bes \major \autoBeamOff

d8.^\f c16 | bes8.[( c16)] bes8.[( a16)] g8.[( f16)] |

ees2 c'8. bes16 | a8.[( bes16)] a8.[( g16)] f8.( ees16)] |

d2 bes8. bes16 | f4. f8 f4 | bes2 r4 | R2.*3 r4 r }

\addlyrics { In the gob -- let a -- lone, In the gob -- let a -- lone, No de -- cep -- tion is found. }

\new PianoStaff <<

\new Staff <<

\new Voice \relative f'' { \key bes \major \stemUp

<f bes,>8. <ees a,>16 |

<d bes>8. <ees a,>16 <d bes>8. c16 bes8. a16 |

g2 ees'8. d16 | c8. d16 c8. bes16 a8. g16 | f2 d8. ees!16 |

f4.^( g8 <f c>4) | bes2 f8.\f g16 | a8. bes16 c8. d16 ees8. f16

g4^( f) d8.^( ees16) | f4 ees8.^( d16) <c a>8.^( bes16) | bes2 }

\new Voice \relative f' { \stemDown

f4 | f f8. fis16 g8. d16 | ees2 <ees g>8. e16 |

f4 f8. e16 f8. a,16 | bes2 bes4 _~ | <bes c>2 a4 |

bes2 f'8._\markup \italic "Sym." g16 |

a8. bes16 c8. d16 ees8. f16 | g,8. a16 bes4 bes |

<bes f> <bes g> ees, | d2 } >>

\new Staff \relative d' { \clef bass \key bes \major

<d d,>8. <c c,>16 | bes8._\markup \small "8vi" c16 bes8. a16 g8. f16 |

ees4 ees, c''8. bes16 | a8. bes16 a8. g16 f8. ees16 |

d4 d, <bes' f'> | << { f' f f d } \\ { <c f,> q q bes } >>

<bes bes,> <d d,>8. <ees ees,>16 |

f8._\markup \small "8vi" g16 a8. bes16 c8. d16 |

<ees ees,>4( <d d,>) <g, g,> | <d d,> <c c,> <f f,> |

<f bes,>_\markup \small \center-column { "Turn to" "Second Verse" } <bes, bes,> \bar ".." } >>

>> }](../../I/53ebb55ea205100a30808e9c84529524.png.webp)

![#(set-global-staff-size 17)

\header { tagline = ##f }

\layout { indent = #0 }

\new Score { <<

\new Staff \relative f' { \key bes \major \time 3/4 \partial 4 \autoBeamOff \mark \markup { \small \caps "Second Verse" } \override Score.Rest.style = #'classical \override Score.BarNumber #'break-visibility = #'#(#f #f #f)

f8. f16 | bes8.[( a16)] bes4 d8.[( c16)] | bes2 f8. f16 |

c'8.[( bes16)] c4 ees8.[( d16)] | c2 bes8.[( a16)] |

g8.[( f16)] g4 c8.[( bes16)] | %end line 1

a8.[( g16)] a4 d8.[( c16)] | bes8.[( a16)] bes4 ees8.[( d16)] |

c2 f8.[( ees16)] | d8.[( c16)] bes8.[( a16)] g8.[( f16)] |

ees4 d d8.[( ees16)] | %end line 2

f4 ees'8.[( d16)] c8.[( bes16)] | bes2 f8. f16 | bes4 r8 a bes4 |

c4 r8 a f4 | d' c8.[( bes16)] a8.[( g16)] | f2 f'8.[( ees16)] |%l3

d8.[( ees16)] d8.[( c16)] bes8.[( a16)] | g2 ees'8.[( d16)] |

c8.[( d16)] c8.[( bes16)] a8.[( g16)] | f2 d8. ees16 |

f4. g8 f4 | bes,2 }

\addlyrics { In the days of our youth, when the heart's in its spring, And dreams that af -- fec -- tion can ne -- ver take wing, And dreams that af -- fec -- tion can ne -- ver take wing; I had friends, who has not? But what tongue will a -- ver That friends ro -- sy wine, That friends, ro -- sy wine, are so faith -- ful as thou }

\new PianoStaff <<

\new Staff <<

\new Voice \relative f' { \key bes \major \stemUp

f8.\p f16 | bes8.^( a16 bes4) <d bes>8. <c a>16 |

<bes d,>2 f8. f16 | c'8.^( bes16 c4) ees8. d16 | c2 bes8. a16 |

g8.^( f16 g4) c8. bes16 | %end line 1

a8.^( g16 a4) d8. c16 | bes8.^( a16 bes4) ees8. d16 |

c2 f8. ees16 | d8. c16 bes8. a16 g8. f16 |

ees4^( d) d8. ees16 | %end line 2

f4 ees'8. d16 <c a>8. bes16 | bes2 \bar ".." f8. f16 |

<bes f>4 r8 a bes4 | c4. a8 f4 | d' c8. bes16 a8. g16 |

<f a,>2 f'8. ees!16 | %line 3

d8. ees16 d8. c16 bes8. a16 | g2 ees'8. d16 |

c8. d16 c8. bes16 a8. g16 | f2 d8. ees16 | f4. g8 f4 | bes,2

}

\new Voice \relative d' { \stemDown

r4 | d f f8. ees16 | s2 r4 | a g <g c>8. bes16 | a2 <f bes,>4 |

<ees bes>2 <ees g>4 | %end line 1

<f c>2 <a fis d>4 | <g d>2 <g c>8. bes16 | a2 <c f,>4 |

f,8. a16 g8. f16 ees8. bes16 | a4_( bes) bes | %end line 2

bes <ees g> ees | d2 r4 | bes s8 ees d4 | <f c>2 f4 |

<f bes> f8. <d g>16 <c f>8. <bes e>16 | s2 f'4 | %end line 3

f f8. fis16 g8. d16 | ees2 <ees g>8. e16 | f4 f8. e16 f8. a,16

bes2 bes4 _~ | <bes c>2 <a c>4 | s2

}

>>

\new Staff \relative b, { \clef bass \key bes \major

r4 | bes d f | bes bes, r | f' ees c | f f, d' | ees2 c4 | %line1

f2 d4 | g2 ees4 | f2 a4 | bes8. fis16 g8. d16 ees8. d16 |

c4( bes) g' | %end line 2

d4 c f | bes bes, r | d r8 c bes4 | a4. c8 f4 |

bes, a8. bes16 c8. c16 | f4 f, <d' d'>8. <c c'>16 | %end line 3

bes'8. c16 bes8. a16 g8. f16 | ees4 ees, c''8. bes16 |

a8. bes16 a8. g16 f8. ees16 | d4 d, <bes' f'> |

<f' c f,> q q | <d bes> <bes bes,> \bar ".."

}

>>

>> }](../../I/d9a734a80f9c731ef7c4555c1577b275.png.webp)

5

![\version "2.18.2"

#(set-global-staff-size 17)

\header { tagline = ##f }

\layout { indent = #0 }

\new Score { <<

\new Staff \relative f'' { \key bes \major \time 3/4 \partial 4 \override Score.TimeSignature #'stencil = ##f \override Score.Rest.style = #'classical \override Score.BarNumber #'break-visibility = #'#(#f #f #f) \mark \markup \bold "CHORUS." \autoBeamOff

f8.[(^\f ees16)] | d8.[( ees16)] d8.[( c16)] bes8.[( a16)] |

g2 ees'8.[( d16)] | c8.[( d16)] c8.[( bes16)] a8.[( g16)] |

f2 d8. ees16 | f4. g8 f4 bes,2 r4 | R2.*3 r4 r }

\addlyrics { That friends, ro -- sy wine, That friends, ro -- sy wine, are as faith -- ful as thou. }

\new Staff \relative bes' { \key bes \major \clef alto \autoBeamOff

bes8.[(^\f a16)] | bes8.[( a16)] bes8.[( fis16)] g8.[( d16)] |

ees2 g8.[( e16)] | f4 f8.[( e16)] f8.[( g16)] | bes,2 bes8. bes16 |

c4. c8 c4 | bes2 r4 | R2.*3 r4 r }

\addlyrics { That friends, ro -- sy wine, That friends, ro -- sy wine, are as faith -- ful as thou. }

\new Staff \relative f' { \clef tenor \key bes \major \autoBeamOff

f8.[(^\f f16)] | f4 f8.[( d16)] d8.[( f16)] | bes,2 c8.[( g16)] |

c8.[( bes16)] c4 c8.[( a16)] | bes2 f8. bes16 | bes4. bes8 a4 |

bes2 r4 | R2.*3 r4 r }

\addlyrics { That friends, ro -- sy wine, That friends, ro -- sy wine, are as faith -- ful as thou. }

\new Staff \relative d' { \clef bass \key bes \major \autoBeamOff

d8.[(^\f c16)] | bes8.[( c16)] bes8.[( a16)] g8.[( f16)] |

ees2 c'8.[( bes16)] | a8.[( bes16)] a8.[( g16)] f8.( ees16)] |

d2 bes8. bes16 | f4. f8 f4 | bes2 r4 | R2.*3 r4 r }

\addlyrics { That friends, ro -- sy wine, That friends, ro -- sy wine, are as faith -- ful as thou. }

\new PianoStaff <<

\new Staff <<

\new Voice \relative f'' { \key bes \major \stemUp

<f bes,>8. <ees a,>16 |

<d bes>8. <ees a,>16 <d bes>8. c16 bes8. a16 |

g2 ees'8. d16 | c8. d16 c8. bes16 a8. g16 | f2 d8. ees!16 |

f4.^( g8 <f c>4) | bes2 f8.\f g16 | a8. bes16 c8. d16 ees8. f16

g4^( f) d8.^( ees16) | f4 ees8.^( d16) <c a>8.^( bes16) | bes2 }

\new Voice \relative f' { \stemDown

f4 | f f8. fis16 g8. d16 | ees2 <ees g>8. e16 |

f4 f8. e16 f8. a,16 | bes2 bes4 _~ | <bes c>2 a4 |

bes2 f'8._\markup \italic "Sym." g16 |

a8. bes16 c8. d16 ees8. f16 | g,8. a16 bes4 bes |

<bes f> <bes g> ees, | d2 } >>

\new Staff \relative d' { \clef bass \key bes \major

<d d,>8. <c c,>16 | bes8._\markup \small "8vi" c16 bes8. a16 g8. f16 |

ees4 ees, c''8. bes16 | a8. bes16 a8. g16 f8. ees16 |

d4 d, <bes' f'> | << { f' f f d } \\ { <c f,> q q bes } >>

<bes bes,> <d d,>8. <ees ees,>16 |

f8._\markup \small "8vi" g16 a8. bes16 c8. d16 |

<ees ees,>4( <d d,>) <g, g,> | <d d,> <c c,> <f f,> |

<f bes,>_\markup \small \center-column { "Turn to" "Third Verse" } <bes, bes,> \bar ".." } >>

>> }](../../I/6a58dfe16c042001739b17a6c928edf6.png.webp)

![#(set-global-staff-size 17)

\header { tagline = ##f }

\layout { indent = #0 }

\new Score { <<

\new Staff \relative f' { \key bes \major \time 3/4 \partial 4 \autoBeamOff \mark \markup { \small \caps "Third Verse" } \override Score.Rest.style = #'classical \override Score.BarNumber #'break-visibility = #'#(#f #f #f)

f8. f16 | bes8.[( a16)] bes4 d8.[( c16)] | bes2 f8. f16 |

c'8.[( bes16)] c4 ees8.[( d16)] | c2 bes8.[( a16)] |

g8.[( f16)] g4 c8.[( bes16)] | %end line 1

a8.[( g16)] a4 d8.[( c16)] | bes8.[( a16)] bes4 ees8.[( d16)] |

c2 f8.[( ees16)] | d8.[( c16)] bes8.[( a16)] g8.[( f16)] |

ees4 d d8.[( ees16)] | %end line 2

f4 ees'8.[( d16)] c8.[( bes16)] | bes2 f8. f16 | bes4 r8 a bes4 |

c4 r8 a f4 | d' c8.[( bes16)] a8.[( g16)] | f2 f'8.[( ees16)] |%l3

d8.[( ees16)] d8.[( c16)] bes8.[( a16)] | g2 ees'8.[( d16)] |

c8.[( d16)] c8.[( bes16)] a8.[( g16)] | f2 d8. ees16 |

f4. g8 f4 | bes,2 }

\addlyrics { When the sea -- son of youth and its jol -- li -- ty's past, For re -- fuge we fly to the gob -- let at last; For re -- fuge we fly to the gob -- let at last. Then we find, who do not? in the flow of the soul, That truth, as of yore, That truth as of yore, is con -- fined to the bowl. }

\new PianoStaff <<

\new Staff <<

\new Voice \relative f' { \key bes \major \stemUp

f8.\p f16 | bes8.^( a16 bes4) <d bes>8. <c a>16 |

<bes d,>2 f8. f16 | c'8.^( bes16 c4) ees8. d16 | c2 bes8. a16 |

g8.^( f16 g4) c8. bes16 | %end line 1

a8.^( g16 a4) d8. c16 | bes8.^( a16 bes4) ees8. d16 |

c2 f8. ees16 | d8. c16 bes8. a16 g8. f16 |

ees4^( d) d8. ees16 | %end line 2

f4 ees'8. d16 <c a>8. bes16 | bes2 \bar ".." f8. f16 |

<bes f>4 r8 a bes4 | c4. a8 f4 | d' c8. bes16 a8. g16 |

<f a,>2 f'8. ees!16 | %line 3

d8. ees16 d8. c16 bes8. a16 | g2 ees'8. d16 |

c8. d16 c8. bes16 a8. g16 | f2 d8. ees16 | f4. g8 f4 | bes,2

}

\new Voice \relative d' { \stemDown

r4 | d f f8. ees16 | s2 r4 | a g <g c>8. bes16 | a2 <f bes,>4 |

<ees bes>2 <ees g>4 | %end line 1

<f c>2 <a fis d>4 | <g d>2 <g c>8. bes16 | a2 <c f,>4 |

f,8. a16 g8. f16 ees8. bes16 | a4_( bes) bes | %end line 2

bes <ees g> ees | d2 r4 | bes s8 ees d4 | <f c>2 f4 |

<f bes> f8. <d g>16 <c f>8. <bes e>16 | s2 f'4 | %end line 3

f f8. fis16 g8. d16 | ees2 <ees g>8. e16 | f4 f8. e16 f8. a,16

bes2 bes4 _~ | <bes c>2 <a c>4 | s2

}

>>

\new Staff \relative b, { \clef bass \key bes \major

r4 | bes d f | bes bes, r | f' ees c | f f, d' | ees2 c4 | %line1

f2 d4 | g2 ees4 | f2 a4 | bes8. fis16 g8. d16 ees8. d16 |

c4( bes) g' | %end line 2

d4 c f | bes bes, r | d r8 c bes4 | a4. c8 f4 |

bes, a8. bes16 c8. c16 | f4 f, <d' d'>8. <c c'>16 | %end line 3

bes'8. c16 bes8. a16 g8. f16 | ees4 ees, c''8. bes16 |

a8. bes16 a8. g16 f8. ees16 | d4 d, <bes' f'> |

<f' c f,> q q | <d bes> <bes bes,> \bar ".."

}

>>

>> }](../../I/2dbeec21cf6472e58a455e126b1ae719.png.webp)

7

![\version "2.18.2"

#(set-global-staff-size 17)

\header { tagline = ##f }

\layout { indent = #0 }

\new Score { <<

\new Staff \relative f'' { \key bes \major \time 3/4 \partial 4 \override Score.TimeSignature #'stencil = ##f \override Score.Rest.style = #'classical \override Score.BarNumber #'break-visibility = #'#(#f #f #f) \mark \markup \bold "CHORUS." \autoBeamOff

f8.[(^\f ees16)] | d8.[( ees16)] d8.[( c16)] bes8.[( a16)] |

g2 ees'8.[( d16)] | c8.[( d16)] c8.[( bes16)] a8.[( g16)] |

f2 d8. ees16 | f4. g8 f4 bes,2 r4 | R2.*3 r4 r }

\addlyrics { That truth, as of yore, That truth, as of yore, is con -- fined to the bowl. }

\new Staff \relative bes' { \key bes \major \clef alto \autoBeamOff

bes8.[(^\f a16)] | bes8.[( a16)] bes8.[( fis16)] g8.[( d16)] |

ees2 g8. e16 | f4 f8.[( e16)] f8.[( g16)] | bes,2 bes8. bes16 |

c4. c8 c4 | bes2 r4 | R2.*3 r4 r }

\addlyrics { That truth, as of yore, That truth, as of yore, is con -- fined to the bowl. }

\new Staff \relative f' { \clef tenor \key bes \major \autoBeamOff

f8.^\f f16 | f4 f8.[( d16)] d8.[( f16)] | bes,2 c8.[( g16)] |

c8.[( bes16)] c4 c8.[( a16)] | bes2 f8. bes16 | bes4. bes8 a4 |

bes2 r4 | R2.*3 r4 r }

\addlyrics { That truth, as of yore, That truth, as of yore, is con -- fined to the bowl. }

\new Staff \relative d' { \clef bass \key bes \major \autoBeamOff

d8.[(^\f c16)] | bes8.[( c16)] bes8.[( a16)] g8.[( f16)] |

ees2 c'8.[( bes16)] | a8.[( bes16)] a8.[( g16)] f8.( ees16)] |

d2 bes8. bes16 | f4. f8 f4 | bes2 r4 | R2.*3 r4 r }

\addlyrics { That truth, as of yore, That truth, as of yore, is con -- fined to the bowl. }

\new PianoStaff <<

\new Staff <<

\new Voice \relative f'' { \key bes \major \stemUp

<f bes,>8. <ees a,>16 |

<d bes>8. <ees a,>16 <d bes>8. c16 bes8. a16 |

g2 ees'8. d16 | c8. d16 c8. bes16 a8. g16 | f2 d8. ees!16 |

f4.^( g8 <f c>4) | bes2 f8.\f g16 | a8. bes16 c8. d16 ees8. f16

g4^( f) d8.^( ees16) | f4 ees8.^( d16) <c a>8.^( bes16) | bes2 }

\new Voice \relative f' { \stemDown

f4 | f f8. fis16 g8. d16 | ees2 <ees g>8. e16 |

f4 f8. e16 f8. a,16 | bes2 bes4 _~ | <bes c>2 a4 |

bes2 f'8._\markup \italic "Sym." g16 |

a8. bes16 c8. d16 ees8. f16 | g,8. a16 bes4 bes |

<bes f> <bes g> ees, | d2 } >>

\new Staff \relative d' { \clef bass \key bes \major

<d d,>8. <c c,>16 | bes8._\markup \small "8vi" c16 bes8. a16 g8. f16 |

ees4 ees, c''8. bes16 | a8. bes16 a8. g16 f8. ees16 |

d4 d, <bes' f'> | << { f' f f d } \\ { <c f,> q q bes } >>

<bes bes,> <d d,>8. <ees ees,>16 |

f8._\markup \small "8vi" g16 a8. bes16 c8. d16 |

<ees ees,>4( <d d,>) <g, g,> | <d d,> <c c,> <f f,> |

<f bes,> <bes, bes,> \bar ".." } >>

>> }

\markup { \column { \line { \caps "Fourth Verse." }

\line { Long life to the grape; and when summer is flown, }

\line { The age of our nectar shall gladden my own, }

\line { Let us drink! who would not? since through life's varied round }

\line { In the goblet alone no deception is found. } } }](../../I/7369dcbf25afaabbc6079120b3ffa0e7.png.webp)

Miss Nyren continues: 'He was himself a temperate man, though he wrote the music for this convivial song and a panegyric on "good strong ale". He was quite as enthusiastic about music as cricket, and in his old age much enjoyed reading over the score of Novello's masses and other music, saying he could imagine he heard the sound of each instrument.

'For thirteen years he was honorary conductor or choir master of the choir of St. Mary's, Moorfields, where Novello was organist, and five years after his death the choir sang, on June 26, 1 842, in memory of him his own "Ave Verum", with chorus. Vincent Novello was at the organ, and Miss Dolby and Miss Lucumbe and Gamballi were the solo singers.

'He was an exceptionally strong man, as the following anecdote will prove. My father well remembered going with his father to see some great boxing contest, where there was a great crowd, and John Nyren senior felt a hand in his coat pocket; he quickly caught it by the wrist and firmly held it, lifting the culprit, a boy, up by it for the crowd to see, and then let him go, thinking him sufficiently punished.

'In one of my grandfather's visits to Belgium an archery fête was in progress. He had never handled a bow, but on being asked to try his skill, did so, and his correct eye and steady hand enabled him to place the arrow exactly in the centre of the bull's-eye. He was asked to shoot again; but he courteously declined, simply saying: "I have shown you what I can do."' Simply; but shrewdly too, I guess.

'John Nyren was never a good man of business, being too kind in helping others to enrich himself. He was a calico printer on a large scale, but his premises were burnt down, and he lost a great deal of property. He and his wife were always ready to help those in trouble of any kind, and those who had the privilege of knowing them have told me how all their friends, and even acquaintances, when in sorrow or any difficulty, always went to consult "old Mr. and Mrs. Nyren", their sympathy and advice being much valued, especially by young people.

'Their family consisted of two sons and five daughters; two others died young. The eldest son, Henry, never married; the youngest son, John William, only did so some years after his father's death, and left three daughters—still living. His little son, the only grandson of John Nyren, who bore his name, died young, and was buried close to his grandfather. Three of John Nyren's daughters married, and have left many descendants, but none named Nyren. One of his daughters became Lady Abbess of the English convent at Bruges.

'My grandfather was very fond of all animals, but more especially dogs; he generally had one or two about him. He was once bitten by a mad one, but happily no bad results ensued, though it was reported he had died from the effects. It is a rather curious fact that the Duke of Richmond, who afterwards died from the bite of a tame fox, and who had a great dread of hydrophobia, while strolling about Lord's cricket ground several times asked my grandfather about this very unpleasant experience; asking many questions and taking much interest in all the details.

John Nyren was very partial to the little black Kentish cherry, and for many years one of his "noble playmates" sent him annually a hamper full of them, which he always received with boyish pleasure, at once opening it himself and enjoying the fruit with his family and any children who happened to be with him.

'There is no doubt John Nyren himself wrote the Young Cricketer's Tutor and Cricketers of My Time; Cowden Clarke only edited them. It was Cowden Clarke who suggested that he should write and print his cricketing recollections, and very much amused and astonished the old gentleman by the idea.'

Here Miss Nyren's manuscript ends, bringing us to controversial ground. Nyren's title-page describes Cowden Clarke as the editor, and Clarke's account of the making of the book is that it was 'compiled from unconnected scraps and reminiscences during conversations'. In other words, Clarke acted as a reasonably enfranchised stenographer. Mrs. Cowden Clarke, in My Long Life, says something of her husband's share in Nyren's book, referring to Nyren as 'a vigorous old friend who had been a famous cricketer in his youth and early manhood, and who, in his advanced age, used to come and communicate his cricketing expressions to Charles with chuckling pride and complacent reminiscence'. One thing is certain and that is that Clarke, who wrote much in the course of his life, never wrote half so well again as for Nyren; and this is an important piece of evidence in favour of his duties being chiefly the reproduction of the old cricketer's racy talk. I have seen, I think in the Tatler, Leigh Hunt's paper, an original description of a match by Cowden Clarke, which contains no suggestion of the spirit of the 'Tutor'. At the same time, I must confess that the little sketch of a cricket festivity from John Nyren's unaided hand, which I quote below, is also so unlike the 'Tutor' as to cause us to wish that Cowden Clarke had been reporting his friend then also. Neither man did such spirited work alone as when the two were together.

The best account of John Nyren is that which Cowden Clarke wrote for the second edition of their book, in 1840, after Nyren's death, beginning thus: 'Since the publication of the First Edition of this little work, the amiable Father of it has been gathered to the eternal society of all good men.' Cowden Clarke continues:—'My old friend was a "good Catholic"—"good," I mean, in the mercantile acceptation of the term—a "warm Catholic"; and "good" in the true sense of the word I declare he was; for a more single- and gentle-hearted, and yet thoroughly manly man I never knew; one more forbearing towards the failings of others, more unobtrusively steady in his own principles, more cheerfully pious; more free from cant and humbug of every description.

'He possessed an instinctive admiration of everything good and tasteful, both in nature and art. He was fond of flowers, and music, and pictures; and he rarely came to visit us without bringing with him a choice specimen of a blossom, or some other natural production; or a manuscript copy of an air which had given him pleasure. And so, hand in hand with these simple delights, he went on to the last, walking round his garden on the morning of his death.

'Mr. Nyren was a remarkably well-grown man, standing nearly 6ft., of large proportions throughout, big-boned, strong, and active. He had a bald, bullet head, a prominent forehead, small features, and little deeply-sunken eyes. His smile was as sincere as an infant's. If there were any deception in him, Nature herself was to blame in giving him those insignificant, shrouded eyes. They made no show of observation, but they were perfect ministers to their master. Not a thing, not a motion escaped them in a company, however numerous. Here was one secret of his eminence as a Cricketer. I never remember to have seen him play; but I have heard his batting, and fielding at the point, highly commended. He scarcely ever spoke of himself, and this modesty will be observed throughout his little Book. He had not a spark of envy; and, like all men of real talent, he always spoke in terms of honest admiration of the merits of others.'

Leigh Hunt wrote thus, when reviewing the Young Cricketer's Tutor ('Messrs. Clarke and Nyren's pleasant little relishing book'), in the London Journal for May 21, 1834: 'It is a pity the reader cannot have the pleasure of seeing Mr. Nyren, as we have had. His appearance and general manner are as eloquent a testimony to the merits of his game as any that he or his friend has put upon paper. He is still a sort of youth at seventy, hale and vigorous, and with a merry twinkle of his eye, in spite of an accident some years ago—a fall—that would have shattered most men of his age to pieces. A long innings to him in life still, and to all friends round the wicket.'

It was a few weeks after this review of Nyren's book that Leigh Hunt printed in the London Journal a letter from the old cricketer (not so old as he had been called, however), describing a cricket festival, which is notable chiefly for the masterly way in which he avoids describing the match itself. If ever a reader was disappointed, it is surely here! It is as though Paderewski stepped to the piano and—recited a poem; or Cinquevalli, with all his juggling implements about him, delivered a lecture. But the little article has such a pleasant naïvete that we must forgive the omissions.

To the Editor of the London Journal.

'Bromley, Middlesex,

'June 25 1834.

'My Dear Sir,

'The wise men of the East invited me to stand umpire at a cricket match, the married men against the bachelors. The day was highly interesting, and I cannot forbear giving you a short account of it. If you can take anything from the description I give you for your paper, do it any way you like; this will be only a rough sketch. I call these gentlemen 'the wise men of the East', as they will not suffer their names in print, and they live at the East End of London.

'When we arrived at the place of our destination I was both surprised and delighted at the beautiful scene which lay before me. Several elegant tents, gracefully decked out with flags and festoons of flowers, had been fitted up for the convenience of the ladies; and many of these, very many, were elegant and beautiful women. I am not seventy; and "the power of beauty I remember yet". I am only sixty-eight! Seats were placed beneath the wide-spreading oaks, so as to form groups in the shade. Beyond these were targets for ladies, who love archery, the cricket ground in front.

'The carriages poured in rapidly, and each party as they entered the ground was received with loud cheers by such of their friends as had arrived before them. At this time a band of music entered the ground, and I could perceive the ladies' feathers gracefully waving to the music, and quite ready for dancing. However, the band gave us that fine old tune "The Roast Beef of Old England".

'We entered a large booth, which accommodated all our party; a hundred and thirty sat down to the déjeuner. Our chairman was young, but old in experience. Many excellent speeches were made; and ever and anon the whole place rang with applause. After this the dancing commenced—quadrilles, gallopade, etc., etc. It was, without exception, the most splendid sight that I ever witnessed, and reminded one far more of the descriptions we read of fairyland than of any scene in real life. The dancing was kept up with great spirit, till the dew of heaven softly descended on the bosoms of our fair countrywomen.

'Not a single unfortunate occurrence happened to damp the pleasure of this delightful party. Had you been with us you would have sung "Oh, the Pleasures of the Plains", etc., etc. How is it that we have so few of these parties? Can any party in a house compare with it? God bless you and yours.

'John Nyren.

'P.S. The cricket match was well contested, the bachelors winning by three runs only.'[1]

Nyren's book (of which the present is the fourth modern reprint[2]) stands alone in English literature. It had no predecessor; it has had no successor. The only piece of writing that I can find worthy to place beside it is Hazlitt's description of Cavanagh, the fives player, which is full of gusto—the gusto that comes of admiration and love. There is no other way—one must keep to one's friends; the inter-county game and its players have grown too public, too commercial, for any wider treatment to be of real merit. But I doubt very much if any more really great literature will collect about the pitch. The fact that Tom Emmett was allowed to die, a year or so ago, without a single tribute worth the name being written is a very serious sign. There was a 'character', if the world ever saw one; but not one of his old friends or associates, not one of his old pupils at Rugby, seems to have thought it worth while to set down any celebration of him. That seems to me very unfortunate, and very significant. In the new bustle of county championships, too many matches, and journalistic exploitation, individuals are being lost.

John Nyren died at Bromley on June 28, 1837. He had been living for some time, with his son, in the old royal palace there. If the reader—the next time that he visits South Kensington Museum—will make a point of seeing the carved overmantel from Bromley Palace which is preserved there, he will have before him a very tangible memento of the old cricketing gentleman, for it was taken from Nyren's room when the house was pulled down.

- ↑ Leigh Hunt, whose attitude to his contributors and readers was always paternal, appends some notes, of which I quote one: '"The world!" The man of fashion means St. James's by it; the mere man of trade means the Exchange, and a good, prudent mistrust. But cricketers, and men of sense and imagination, who use all the eyes and faculties God has given them, mean His beautiful planet, gorgeous with sunset, lovely with green fields, magnificent with mountains—a great rolling energy, full of health, love, and hope, and fortitude, and endeavour. Compare this world with the others—no better than a billiard ball or a musty plum.'

- ↑ The others were Messrs. Sonnenschein's, Mr. Ashley-Cooper's and Mr. Whibley's. To Mr. Whibley, I believe, belongs the honour of discovering or re-discovering the literary merits of the work. It was his praise of it in the Scots or National Observer that first sent many readers to the original. E. V. L.