CHAPTER VI.

In which Professor Higginson Begins to Taste the Sweets of Fame

When Professor Higginson reached the door of his lodgings the Ormeston day had begun.

The house was one of a row of eighteenth-century buildings, dignified and a trifle decayed, representing in the geology of the town the strata of its first mercantile fortunes. It was here that the first division between the rich and poor of industrial Ormeston had begun to show itself four generations ago, and these roomy, half-deserted houses were the first fruits of that economic change.

But Professor Higginson was not thinking of all that as he came up to the well-remembered door (which in the despair of the past nights he had sometimes thought he would never see again). He was thinking of how he looked with his horribly crushed and dirty shirt front, his ruined collar, and his bedraggled evening clothes upon that bright morning. In this reflection he was aided by the fixed stares of the young serving-maids who were cleaning the doorsteps and the unrestrained remarks of youths who passed him in their delivery of milk. The first with their eyes, the second more plainly with their lips, expressed the opinion that he was no longer of an age for wanton pleasures, and he was annoyed and flustered to hear himself compared to animals of a salacious kind, notably the goat.

It was not to be wondered at that, being what he was, a man who had never had to think or act in his life. Professor Higginson's one desire was to put his familiar door between himself and such tormentors.

He rang the bell furiously and knocked more furiously still. An errand-boy, a plumber's apprentice upon his way to work, and a road scavenger joined a milkman, and watched him at this exercise in a little group. It was a group which threatened to become larger, for Ormeston is an early town. Professor Higginson, forgetting that Mrs. Randle, his landlady, might not be up at such an hour, gave another furious assault upon the knocker, suddenly remembered his latch key, brought it out, and was nervously feeling for the keyhole amid jeers upon his aim, when the door was suddenly opened and the considerable figure of Mrs. Randle appeared in the passage.

For one moment she looked as people are said to look at ghosts that return from Hell, then with a shriek that startled the echoes of the whole street, she fell heavily against the Professor's unexpecting form, nearly bringing it down the steps.

Mr. Higginson was guilty of a nervous movement of repulsion. A little more and he would have succeeded in shaking off the excellent but very weighty woman who had thus greeted his return, but even as he did so he heard the odious comments of the Ormeston chivalry, notably the milkman, who told him not to treat his wife like a savage. The plumber also called it cruel. It was therefore with some excuse that the great Psychologist thrust the lady of the house within and slammed the door behind him with his heel.

Mrs. Randle was partially recovered, but still woefully shaken. He got past her brutally enough, pushed into the ground floor room in the front of the house, and sat down. He felt the exhaustion of his walk and the irritation of the scene which had just passed to be too much for him. Mrs. Randle, with a large affection, stood at the table before him, leaning heavily upon it with her fists, and saying, "Oh, sir!" consecutively several times, until her emotion was sufficiently calm to permit of rational speech. Then she asked him where he had been.

"It 's the talk of the whole town, sir! Oh! and me too! Never, I never thought to see you again!" at which point in her interrogation Mrs. Randle broke suddenly into a flood of tears, punctuated by sobs as explosive as they were sincere.

She sat down the better to enjoy this relief, and even as she had risen to its climax, and the Professor was being moved to louder and louder objurgation, the bell rang and the hammer knocked in a way that was not to be denied. The unfortunate man caught what glimpse he could from the window, and was horrified to see two officers of the law supported by a crowd grown to respectable dimensions, the foremost members of which were giving accurate information upon all that had happened.

The Philosopher summoned the manhood to open the door and to face his accusers. They were not so startled as Mrs. Randle, who now came up with red and tearful face and somewhat out of breath (but her weeping largely overlain with indignation) to protest against the violation of her house.

The first of the policemen had hardly begun his formal questioning of Professor Higginson, when the second, looking a little closer, recognised his prey. That subtle air which no civilian can hope to possess, and by which, like the savages of Central Africa, the British police convey thought without words or message, acted at once upon the second man, and he adopted a manner of the utmost respect. To prove his zeal he dispersed the crowd of loungers, saluted, and told the Professor that it was his duty to ask him formally certain questions; whereat his colleague—he that had first recognised the great man—added with equal humility that as Mr. Higginson had been lost, and the University moving the police in the matter, it was only their duty to ask what they should do, and what light Mr. Higginson could throw on the affair. There was a report of fighting. To this Mrs. Randle interposed, without a trace of logic, "Fighting yourself!"

The Professor was very glad to answer any questions that might be put to him, and very much relieved when he found that these were no more than what the police required to trace the misadventure of so prominent a citizen: at whose hand he had suffered, or what adventure had befallen him; was it murder—but they saw it was not that; whether the reward which had been offered should be withdrawn, and what clues the Professor could furnish.

Mr. Higginson looked blankly at these men, then his eyes lit with anger. He was upon the very point of pouring out the whole story of his woes, when with that cold wind upon the heart which the condemned feel when they awake to reality upon the morning of execution, he remembered the cheque and was suddenly silent.

"You 'd better leave me!" he muttered. "You 'd better leave me, officer!"

"We were instructed, sir," began the senior man more respectfully than ever—then Professor Higginson bolted to refuge.

"Well, I will see you in a minute; I must put myself right. I am all"

"We quite understand, sir," said the policemen, taking their stations in the ground floor room, and drawing chairs as with the intention of sitting down and awaiting his pleasure.

"I will see you when I can. Mrs. Randle, please bring me some hot water."

And with these words the poor man dashed upstairs to his bedroom upon the first floor.

There are ways of defeating a woman's will when she has passed the age of forty, and these are described in books which deal either with an imaginary world of fiction or with a remote and unattainable past. No living man has dealt with the art, nor can wizards show you an example of it.

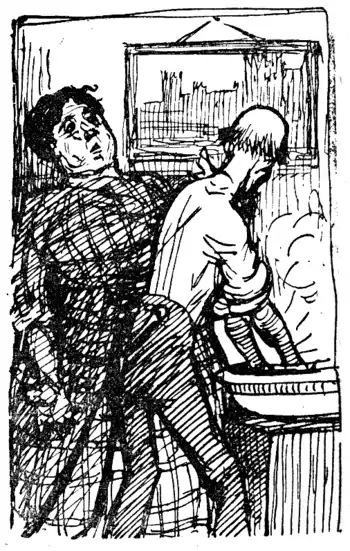

Therefore, when Mrs. Randle returned with the hot water, it was Mrs. Randle that won.

The Professor poked his head through the door and reached out for the can. Mrs. Randle broke his centre, marched for the wash-hand stand, poured out the grateful liquid, tempered it with cold, motherly tested its temperature with her large red hand, and the while opened fire with a rattle of questions, particularly begging him not to tell her anything until he was quite rested. Of course, there were the police (she said), and she would have to tell her own tale, too, and oh, dear, if he only knew what it had been those days! With the Mayor himself, and what not! At each stage in her operations she was careful to threaten a fit of crying.

Professor Higginson's tactics were infantile. They were those of his sex. He took off his evening coat and waistcoat preparatory to washing. Upon minor occasions in the past, mere affairs of outposts, Mrs. Randle had taken cover before this manœuvre; to-day the occasion was decisive, and she stood firm.

"and the Principal of the University too, sir! And his dear young lady! And, oh! when they put that news in the paper, which wasn't true, thanks be to God"

Here, as Mrs. Randle approached tears again, the desperate philosopher threw his braces from his shoulders, plunged his face and hands into the water, and fondly hoped that when he lifted it again the enemy would have fled. But Mrs. Randle was a widow, and the first sound he heard as the water ran out of his ears was the continuing string of lamentations and questionings.

"Where 's the towel?" he asked abruptly.

"Where it 's been since last Monday, sir," said Mrs. Randle. "Since that last Blessed Monday when we thought to lose you for ever! I never thought to change it! I never thought to see you back all of a heap like this!"

"Last Monday?" hesitated Mr. Higginson genuinely enough. His calendar had got a little muddled. "What 's to-day?" he said it easily. Then he saw a look on her face.

To-day the occasion was decisive and she stood firm.

There is a rank in society in which to forget the day of the week has a very definite connotation—it means … it means something wrong with the Brain. Like a flash an avenue of salvation was suggested to the hunted man by Mrs. Randle's look. He could lose those few days! They could disappear from his life—utterly—and with them that accursed business of the Green Overcoat and the fatal cheque-book it had hidden in its man-destroying folds!

In the very few seconds which creative work will take under the influence of hope and terror, the scheme began to elaborate itself in the narrow mind of the poor, persecuted don. He flopped down upon a chair, paused suddenly in the vigorous rubbing of his face with the towel, passed his hand over the baldness of his forehead, and muttered vacantly—

"Where am I?"

"You 're here, sir! Oh, you 're here!" said good, kind Mrs. Randle in an agonised tone, positively going down upon her knees (no easy thing when religion has departed with youth) and laying one hand upon his knee.

The Professor laid his left hand upon hers, passed his right hand again over his face, and gasped in a thin voice—

"Where 's here?"

"In Quebec Street in your own room, sir! Oh, sir, don't you know me? I 'm Martha Randle?"

The Professor looked down at her with weary but forgiving eyes.

"I do now," he said; "it comes back to me now."

"Oh, Lord!" said Martha Randle, "I 'll send the girl for the chemist!" and she was gone.

Women may be stronger than we men, my brothers, but we are more cunning; and when she had gone the Professor, dropping the mask and dressing with extreme alacrity, made himself possible in morning clothes. His plan had developed still further in the few minutes it took him to go downstairs, and as he entered the room where the policemen awaited him, he was his own master and theirs.

They rose at his entrance. He courteously bade them be seated again, and not allowing them to get any advantage of the first word, told them the plain truth in a few simple and cultivated sentences, such as could not but carry conviction to any insufficiently salaried official.

"I think it well, officer," he said, addressing the senior of the two men, "to tell you the truth here privately. I will, of course, put the whole thing later before the proper authorities."

The policemen looked grave and acquiescent.

"The fact is," replied Professor Higginson rapidly, "I had been working very hard at my Address—which you may have heard of."

The two men looked at once as though they had.

"It was for the Bergson Society," he explained courteously, and the older policeman nodded as though he were a member himself.

"Well," went on Professor Higginson in the tone of a man who must out with it at last, "the fact is, there followed—there followed, I am sorry to say, there followed something like a stroke—at any rate, bad nervous trouble. … I have suffered—apparently for some days—from a complete loss of memory."

And having put the matter plainly and simply in such a fashion, Professor Higginson was silent.

"We quite understand, sir," said the senior of the two policemen gravely, sympathetically and respectfully. "There shan't be a word from us, sir, except of course"

"No," said Professor Higginson firmly, "I am determined to do my duty in this matter; those whom it is proper to tell"

At this moment Mrs. Randle, accompanied by a half-dressed servant, herself in an untied bonnet and somewhat out of breath, was heard at the open door with the reluctant and sleepy chemist, who was her medical adviser.

"And he was that bad he thought I was his poor old mother, who 's been dead these twenty years!" went Mrs. Randle's voice outside.

But a moment afterwards, as she came into the inner room, she saw the Professor seated and clothed and in his right mind. He rejected her exuberance.

"Now, Mrs. Randle," he said rather sharply, and forgetting for a moment the natural nervous weakness to be expected of one who had suffered Such Things, "I have told the officers here and I desire you to know it as well."

He glanced at the chemist, rapidly decided that the more people knew his tale the better, and said with intentional flattery—

"I thank you, sir, for coming; you are a medical man."

Then he continued, turning to the policemen again—

"You understand? There is unfortunately very little to say. My last recollection is of leaving Sir John Perkin's house—he was giving a party on—on … wait a moment … it was Monday. I remember having a sort of shock just after getting out of his gate, and then I do not remember anything more until I was approaching this house. It will be Tuesday to-day?"

"No, sir," said the policeman, with grave reverence for one so learned, so distinguished, and at the same time so unique in misfortune. It reminded him of the wonderful things in the Sunday papers, and he believed. "No, sir; to-day is Thursday."

"Thursday?" said the Professor, affecting bewilderment with considerable skill. "Thursday?" he repeated, turning to the chemist, who said solemnly—

"Thursday, sir!"

"Oh, poor dear!" immediately howled Mrs. Randle.

"Be quiet," shouted Professor Higginson very rudely. "If it is Thursday," he continued to the others, dropping his voice again, "this is a more serious thing than I had imagined. Why, three whole days … and yet, wait" (and here he extended one hand and covered his eyes with the other) "I seem to have an impression of … cold meat … a room … voices … no, it is gone."

The younger policeman pulled out a notebook and an extremely insufficient pencil, which was at once short, thick, and bald-headed.

"Lost any valuables, sir?" he began.

The Professor slapped his pockets, and then suddenly remembered that he had changed his clothes.

"No," he mused. "No, not to my knowledge. I had my watch" (he began to tick off on his fingers) "and a few shillings change …" But for the life of him he couldn't decide whether to lose valuables or not. On the whole he decided not to.

"No," (after careful thought), "no, I lost nothing. My boots were very damp as I took them off, if that is any clue."

The younger policeman was rapidly putting it all down in the official shorthand. Habit compelled him to make the outline, "The Prisoner persistently denied" He scratched it out and put, "The Professor told us that he had not" Then came the second question—

"In what part of the town, sir, might it be that you knew yourself again, sir, so to speak?"

"I have told you, close by here," said Professor Higginson.

"Yes, but coming which way like?"

Here was a magnificent opening! He had never thought of that. He considered what was the most central quarter of the town, what least suggested a suburb. He remembered a dirty old mid-Victorian church, now the cathedral, in the heart of the city, and he said—

"St. Anne's, it was close to St. Anne's."

Then he remembered—most luckily—that there were witnesses to his having come up the street from exactly the opposite quarter, and he added—

"At least that 's where I began to remember a little; but I wandered about, I didn't remember the street for a good hour, and even when I came here I was still troubled … Mrs. Randle will tell you"

"Oh," began Mrs. Randle, "Lord knows, he gave a cry that loud on seeing me" but the policeman did not want to hear this.

He put this third question—

"About what time might this be?"

"About," said the Professor, speaking slowly but thinking at his fastest, "about … about three hours ago. It was still dark. It was getting light. I remember going through the streets, getting a little clearer from time to time as to what I was doing and where I was."

The manœuvre was not without wisdom. Had he made the time shorter there would have been inquiries, and they might have lit upon the three men in the shelter, and that detestable Green Overcoat might have come in once more to ruin his life. As it was, whoever the middle-aged person in battered evening clothes may have been who had entered the shelter on that morning, it could not be he. The policeman strapped the elastic over his note-book again.

"That 'll do, sir," he said kindly.

Mrs. Randle was swift to find a couple of glasses of beer, which beverage the uncertain hours of their profession permit the constabulary to consume at any period whatsoever of the day or night, and what I may call "The Great Higginson Lost Memory Case" started on its travels round the world.

During the remainder of that day—the Thursday—Professor Higginson was prodigal enough of his experience. It was a great thing for a Professor of Subliminal Psychology to have come in direct touch in this way with one of the most interesting of psychical phenomena. Everyone he met in the next hours had a question to ask, and every question did Professor Higginson meet with a strange facility; but, alas! with renewed and more complex untruth. Had he any recollections? Yes … Yes. Were there faces? Yes, there were faces. Drawn faces. He could say more (he hinted), for the thing was still sacred to him.

One cross-questioned a little too closely about the sense of Time. Had he an idea of its flight during that singular vision? Yes. Yes … In a way. He remembered a conversation—a long one—and a flight: a flight through space.

What! a flight through space?

He told the story with much fuller details that very morning about noon to his most intimate personal friend, the editor of the second paper in Ormeston.

He told it again at the club at lunch to a small audience with the zest of a man who is describing a duel of his. He told it to a larger audience over coffee after lunch. He went back to arrange matters at the University, and to say that he could take up his work the next morning.

It was to the Dean (who was also a Professor of Chemistry), to the Vice-Principal, and to the Chaplain that he had to unbosom himself on this official occasion. All were curious, and by the time they had cheered him, the desperate man's relation had grown to be one of the most exact and beautiful little pieces of modern psychical experience conceivable. All the functionings of the subconscious man in the absence of a co-ordinating consciousness were falling into place, and the World that is beyond this World had been visited by the least likely of the sons of men.

As one detail suggested another, the necessity for a coherent account bred what mere experience could never have done.

Now and then in these conversations Professor Higginson thought he heard a note of doubt in some inquirer's voice. It spurred him to new confirmations, new lies.

For his mathematical colleague he swore to the fourth dimension; for his historical one, to a conspectus of time. "Little windows into the past," he called it, the horrid man!

Then—then in a moment of whirl he did the fatal thing. It was a Research man called Garden who goaded him.

Garden had said—

"What were the faces? What were the voices? How did they differ from dreams?"

Professor Higginson felt the spur point.

"Garden," he said, facing that materialist with a marvellously solemn look, "Garden … How do you know reality? I saw … I heard." He shuddered, successfully. "Garden," he went on abruptly, "have you ever loved one—who died?"

"Bless you, yes!" answered Garden cheerfully.

"Garden!" continued the Philosopher in a deep but shaken voice, "I too have lost where I loved—and" (he almost whispered the rest) "and we held communion during that brief time."

"What!" said Garden. He stared at the tall, lanky Professor of Psychology. He didn't believe, not a word. But it was the first time he had come across that sort of lunacy, and it shocked him. "What! The Dead?"

Mr. Higginson nodded twice with fixed lips and far-away eyes.

"There is proof," he said, and was gone.

****

Garden stared after him, then he shrugged his shoulders, muttered, "Mad as a hatter!" and turned to go his way. It was about five o'clock.

****

Among other things which the Devil had done in that period with which this story deals was the planting in Ormeston of a certain servant of his, by name George Babcock.

George Babcock had come to Ormeston after a curious and ill-explained, a short and a decisive episode in his life. He had begun as a young theorist, who had startled Europe from the foreign University where he was studying by a thesis now forgotten abroad, but one the memory of which still lingered in England, for a paper had boomed it.

It had been a scornful and triumphant refutation of the Hypnotists of Nancy.

A certain servant of his, by name George Babcock.

George Babcock had rolled the Nancy school over and over, and for a good five years the young English writer, with his perfect command of German, had been the prophet of common sense. "Hypnotism," as that school called their charlatanry, was done for, a series of clumsy frauds, a thing of illusions, special apparatus and lies.

Unfortunately for civilisation, the superstitions of the Hypnotists, as we know, prevailed, and European science has grown ashamed since that day of its earlier and manlier standpoint. It has learnt to talk of auto-suggestion. It has fallen so low as to be interested in Lourdes.

Long before 1890 George Babcock's book was ruined abroad. But George Babcock was a man with a knowledge of the road, and while his reputation, dead upon the Continent, was at its height in England, he suddenly appeared, no longer as a theorist, but as a practising doctor in London. He had borrowed the money for the splash on the strength of that English reputation, which he retained, and for ten years he was a Big Man. It was said that he had saved a great deal of money. He certainly made it. Then there came—no one knows what. The professionals who were most deeply in the know hinted at a quarrel with Great Ladies upon the secrets of his trade—and theirs.

At any rate, for another three years after the little episode, George Babcock's name took a new and inferior position in the Daily Press. It appeared in the lists of City dinners, at meetings, at the head of middle-class "leagues" and "movements" that failed. When it was included in the list of a country-house party that party would not be of quite the first flight, and, what was terribly significant to those few who can look with judgment and pity on the modern world, articles signed by the poor fellow began to appear in too great a quantity in the magazines. He even published three books. It was very sad.

Then came the incorporation of the University of Ormeston, or, as people preferred to call it from those early days, the Guelph University, after the name of a patron, and the Prime Minister's private secretary had been sent to suggest, as the head of the Medical School, the name of George Babcock.

He was neither a knight nor a baronet, but Ormeston did not notice that. The old glamour of his name lingered in that prosperous town. A married cousin of the Mayor of that year, whose wife dined out in London, reported his political power. The merchants and the rest in the newly-formed Senate of the University timidly approached the Great Man, and the Great Man jumped at it.

He had now for five years been conducting his classes at the absurdly low salary of £900 a year.

George Babcock remained after all his escapades and alarms—such as they may have been—a man of energy and of singular organising power, an Atheist of course, and one possessed both of clear mental vision and a sort of bodily determination that would not fail him until his body failed. His face and his shoulders were square, his jaw too was strong, the looseness of his thick mouth was what one would expect from what was known about him by those who knew. His eyes were fairly steady, occasionally sly; his brows and forehead handsomely clean; his hair thick and strongly grey.

This was the figure Garden saw coming up the street towards him as Professor Higginson shambled off, already a distant figure, nearing the gates of the College (for it was in the street without that the Philosopher had met the Research man and made that fatal move).

To say that Garden was glad to meet Babcock would be to put it too strongly; no one was ever glad to meet Babcock. But to say that he was indifferent to the chance of blabbing would not be true; no one is indifferent to the chance of blabbing.

"I say, Babcock," he said, checking the advancing figure with his raised hand, "old Higginson 's gone mad."

Babcock smiled uglily.

"Yes, he has," said Garden, "saying all sorts of things about that little trouble he had. Saw ghosts!"

"They all do," said Babcock grimly.

"Oh, yes, I know," answered Garden, eager for the importance of his tale, "but he 's got it all pat! Says he can prove it!"

Garden nodded mysteriously.

"He gave me some details, you know," went on Garden most irresponsibly; then he pulled himself up. He wanted to have something important to say, but he was a nervous man in handling those tarradiddles which are the bulk of interesting conversation.

Babcock looked sceptical.

"What sort of details?" he sneered.

"Oh, I 'm not allowed to tell you," said Garden uneasily, "but it was very striking, really it was."

Then suddenly he broke away. He felt he might be led on, and he didn't want to make a fool of himself. He rather wished he hadn't spoken. Babcock let him go, and as Garden disappeared in his turn the Doctor paced more slowly. He was not disturbed, but he was interested.

Everyone in the University had heard of Higginson's Spiritual Experience, everyone was already talking of it; that wasn't the odd part. The odd part (he mused) was a man like Garden taking it seriously. …

The more Mr. Babcock thought of it the more favourably a certain possibility presented itself.

He made his way towards the telephone-room at the Porter's Lodge, asked them to call up a number in London, and waited patiently until he obtained it.

He took the full six minutes, and it will interest those who reverence our ancient constitution to know that the person to whom George Babcock was talking was a peer—one of those few peers who live at the end of a wire, and not only a peer but the owner of many things.

The man at the other end of the wire was the owner of railway shares innumerable, for the moment of stores of wheat (for he was gambling in that), but in particular of many newspapers, chief of which a sheet which had thrust back into their corners all older, milder things, and had come to possess the mind of England. This premier newspaper was called The Howl; nor did the writer of that letter own The Howl only, but altogether some eighty other rags; nor in this country only was he feared, though he was more feared in this country than in any other.

It was his boast that he could make and unmake men, and every politician in turn had blacked his boots, and he had made judges, and had at times decided upon peace and war. A powerful man; known to his gutter (before he bought his peerage) as Mr. Cake; a flabby man—and vulgar? Oh! my word!

This man at the other end of the wire knew much, too much, about George Babcock, and George Babcock knew that he knew it. From time to time George Babcock, sickening at the recollection of such knowledge privy only to him and to his lordship, was moved to services which, had he been a free man, he would not have undertaken. He was about to perform such a service now.

He told the story briefly to that telephone receiver. He insisted on the value of it. The man at the other end of the wire was very modern. He had a list of the expresses before him. He told George Babcock to expect a letter that would come up by the six o'clock and reach Ormeston at 8.5. George Babcock would get his instructions by that train. At 8.5, therefore, George Babcock, bound to service and not over-willing, was on the platform, took the packet from the guard, feed him, opened it, and read.

The letter was not type-written. It was a familiar letter, and it was signed of course by a single uninitialed name, for was not its author a peer?

****

Meanwhile, the unfortunate Professor of Psychology was wandering within the College buildings from room to room, from friend to friend, and spreading everywhere as he went a long and tortuous train of falsehood and of doom.

Just before dinner, sitting with the Vice-Principal's wife in her drawing-room, he added one very beautiful little point which had previously escaped him—how during what must have been the middle of his curious trance he had heard the most heavenly singing—he who could not tell one note from another on ordinary days! The Chaplain had already used him before ten o'clock as a proof of the immortality of the soul in his notes for next Sunday's sermon, and a local doctor had been particularly interested to hear, as they met just before dinner, that though he may have had food and drink during that long period, the only thing he could remember was cold meat, and that only as something seen, not as something consumed.

"What kind of cold meat?" the doctor had said; but Professor Higginson, whose brain was not of the poet's type, had only answered, "Oh, just cold meat."

Thus by the evening of that Thursday was the dread process of publicity begun.

That night, while all slept, in the two Ormeston newspaper offices, shut up in their little dog kennels, the leader writers were scribbling away at top speed, dealing with Subliminal Consciousness and the Functions Unco-ordinated by Self-cognisant Co-ordination, the one from the Conservative, the other from the Liberal standpoint.

Even the Socialist weekly paper which went to press on Friday was compelled to have a note upon the subject; but knowing that it must bring in some reference to the nationalisation of the means of production and the Parsonic Fraud, it basely said that Professor Higginson was, like every other supporter of the Bourgeois State, a so-called Christian, in which slander, as I need hardly inform the reader, there was not a word of truth.

And so, having dined well with his Vice-Principal and had his fill, Professor Higginson set out by night to seek his lodgings.