MARSHALL, John, chief justice of the United States: b. Germantown (now Midland), Fauquier County, Va.. 24 Sept. 1755; d. Philadelphia, 6 July 1835. He was the eldest son of Col. Thomas Marshall of Westmoreland County, Va., a distinguished officer in the French War and in the War of Independence, and of Mary Keith, a member of the well-known Randolph family. Thomas Marshall removed from Westmoreland County to Fauquier soon after his marriage; this community was sparsely settled and the educational advantages which he could give his children were meagre, consequently he became their earhest teacher and succeeded in imbuing them with his own love of literature and of history. For two years John Marshall had, as tutor, James Thompson of Scotland and he was sent for one year to the academy of the Messrs. Campbell of Westmoreland County, where James Monroe was also a pupil. He had no college training except a few lectures on law and natural philosophy at William and Mary in 1779. He was always fond of field sports and excelling in running, leaping and quoit throwing. He loved the free natural life of the country, and his long tramps through the woods around his fathers home, Oak Hill, together with his athletic exercises gave him great strength and agility. At 18 he began the study of law, but soon left his studies to enter the Revolutionary army. He was active in endeavoring to enlist men for the service and helped to form and drill a company of volunteers. As a member of his father's regiment he took part in the battle of Great Bridge where he displayed signal valor. In 1776 he became a lieutenant in the 11th Virginia, and the next year was made captain. He served in Virginia, New Jersey, Pennsylvania and New York, always displaying great courage and valor and a cheerful acceptance of hardships and privations. This experience was of untold value to Marshall, it broadened his views and quickened his insight in governmental questions. As he says, he entered the army a Virginian and left it an American. In 1780 during a period of military inactivity he attended a course of law lectures at William and Mary and in 1781, after leaving the army, was granted a license and began the practice of law in Fauquier County. The next year he was elected to the Virginia assembly, and shortly afterward wss made a member of the executive council. He served his State as legislator during eight sessions. In 1784, although he had then removed his residence to Richmond, he was again elected delegate from Fauquier County, and in 1787 served as member from the county of Henrico. When the city of Richmond was granted a representative in the legislature Marshall had the honor of this office which he held from 1788 to 1791. He was also a member of the Federal Convention which met in 1788 to discuss the ratification of the Constitution of the United States, and it was largely due to his convincing arguments that ratification was carried, as the question was hotly debated and the anti-Constitution party had able and detemined representatives. For several years he held no public office and devoted himself entirely to his extensive law practice, but in 1795 was again elected to the legislature. During this session he defended the unpopular “Jay Treaty” with England, and by his overwhelming arguments completely refuted the theory of his opponents that the executive has no power to negotiate a commercial treaty. Marshall's attitude during his service as legislator toward all questions concerning Federal power demonstrated his increasing belief that a strong central government is necessary to real efficiency. In 1783 he had married Mary Ambler, daughter of Jacqueline Ambler, treasurer of the State, and soon after his marriage made his permanent home in Richmond. The honors bestowed on him testify to the esteem in which he was held by the State and by the nation. He refused the Attorney-Generalship and the Ministry to France, but in 1789 accepted the office of Special Envoy to France with Charles Cotesworth Pinckney and Elbridge Gerry. This mission related to the indignities which the French had offered the American navy and attempted to adjust the commercial relations between the two countries. It failed on account of the arrogant attitude of France, but “Marshall's dignified correspondence added greatly to the prestige of America,” and on his return he was welcomed with many evidences of approbation from his grateful countrymen. Yielding to the earnest solicitation of Washington he became a candidate for Congress and was elected a member of that body in 1798. In Congress he was the leader of the Administration party and the greatest debater in the House on all constitutional matters. In one of his most noted speeches he defended the action of President Adams in the case of Jonathan Robbins and proved conclusively that this case was a question of executive and not of judicial cognizance. In 1800 he was made Secretary of State, and in 1801 appointed chief justice of the United States, which office he held until his death in 1835. In 1829 he, like ex-Presidents Madison and James Monroe, was a member of the Virginia convention which met to alter the State constitution, and by his wisdom and moderation did much to prevent radical changes and to thwart the attempts of politicians against the independence of the judiciary. In 1831 his health, hitherto unusually vigorous, began to fail; he underwent a severe surgical operation in Philadelphia and was seemingly restored, but the death of his wife was a great shock and a return of the disease in 1835 proved fatal. He died in Philadelphia, whither he had gone for medical relief, and was buried by the side of his wife in the New-Burying-Ground, now Shockhoe Hill Cemetery, Richmond. The sorrow over the country was deep and widespread; even his bitterest enemies mourned for the kindly, upright man.

Though somewhat ungainly, Marshall was always dignified in appearance; his tall, loosely-jointed figure gave an impression of freedom, while his finely shaped head and strong, penetrating eyes bespoke intelligence and power. Directness and simplicity were his dominant characteristics. He was free from any display of pomp, air of office or studied effect. His unfailing good humor, his benignity, his respect for women, his devotion to wife and family and his well-known reverence for religion made him loved and admired even by those who heartily disliked his political opinions. As chief justice for more than 30 years be rendered numerous decisions which were of prime importance to a nation in process of formation. The faculty which made Marshall invaluable as a jurist was his power of going directly to the core of any matter. No subtleties, no outside issue confused him, his analysis was unerring, his logic incontrovertible; he cared nothing for the graces of rhetoric and made no appeal to the emotions; his power lay in his deep conviction and in his illuminating and progressive argument. At a period when the powers of the Constitution were ill-defined, when our government was experimental, Marshall's decisions in constitutional and international cases were invaluable factors in forming a well-organized Federal government. “He made the Constitution live, he imparted to it the breath of immortality, and its vigorous life at the present hour is due mainly to the wise interpretation he gave to its provisions during his long term of office.” Marshall was the author of numerous reports and papers, of a history of the colonies and of a ‘Life of Washington,’ a book of small literary merit, but containing a mass of valuable authentic information. Consult Cooley, ‘Constitutional History of the United States’ (1889); Margruder, ‘John Marshall’ (1885); Thayer, ‘John Marshall’ (in ‘Beacon Biographies’ series, 1901); Beveridge, A. J., ‘Life of John Marshall’ (1916).

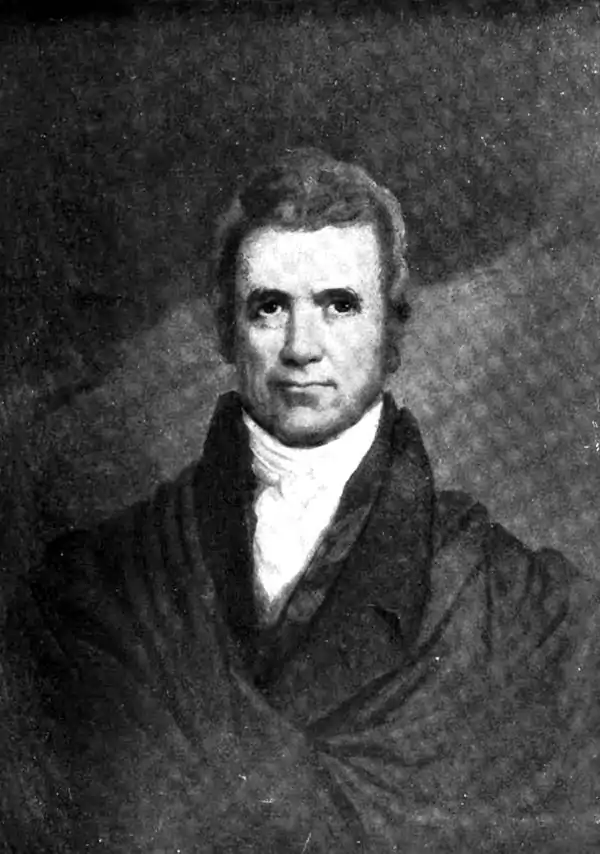

JOHN MARSHALL

Chief Justice United States Supreme Court