THE BOX-STALL

BY MARY HEATON VORSE

MRS. HUMMER stood in the soft dusk, at the remote doorway of the big room, and looked back at the appalling young scarecrow before her.

She swayed slightly from one foot to another, like an elephant at tether, Richard thought. He could not take his eyes from her. He knew he had no business to stare in this glassy, fixed sort of a way at old Hummer. Why old Hummer was the most familiar thing in the world. He could not remember when she had not been their housekeeper. Her sitting-room had always been his refuge from wrath. Yet this big, kindly woman seemed as improbable and as far removed from usual experience as finding a kindly cow gazing at one from one's bedroom door—cows and women being equally absent from German prison camps. How strange in turn he seemed to her he had measured by the tears that sprang to her eyes at sight of him.

So for a moment they stared at each other, not as though across a room, but as if trying to peer at each other over the intolerable cruelties of the past four years since he had run down the steps waving to them and shouting out a gay, "Well, Good-by, Hummer!"—bound for a trip down the Rhine before he went to Cambridge.

Hummer broke the silence with: "You'll have everything you need now for dressing, Mr. Ricky. You'll find your bath ready for you." She switched on the light from the door and hurried away, leaving him staring after her.

Ricky! He had forgotten all about that name. His mother's letters had always begun "My darling Boy," his father's with "Dear Richard." The last time he had ever seen it written was in a letter, ever so long ago, from his cousin Dorothy.

"I have been trying for the last hour," she wrote, "to put down 'Dear Ricky'! but Ricky means out of door, and Surrey lanes, and getting into mischief, and all that part of you that can't be shut up in a German prison camp. They can't have shut up Ricky!"

They had not shut him up. Ricky was as dead as Richard's mother. The news of her death had come to him two years before, not with the clean, deep stab of grief, but as something still farther shutting him off from the life's reality, a window gone through which to look on the world, a thickening of the darkness around him. The news had come when he himself was ill, and when the horror of each individual discomfort of life crowded between him and the realization of grief.

Now, slowly, like a black and bitter tide, a numbing sense of loss invaded him. There came to his mind the words of a letter of his mother, written not long before her death. "It's the eternal silence of this house that's killing me, when I think that we used to scold you for the noise you used to make!" This silence that was killing him, too. A stealthy grief wrapped itself about him. It was not his mother for whom he was grieving—not as one ought to; what he wanted was to be Ricky again. He wanted that, and that was the only thing he did want in life for the moment.

He walked to the glass which was let into the huge wardrobe, a piece of furniture taking up half the wall space, places for hanging on one side, drawers for every conceivable kind of clothes on the other, as solid and resourceful as the Bank of England, presupposing substance of its possessors.

It mirrored forth relentlessly Ricky's scarecrow figure. He looked at himself curiously, as at some distasteful stranger. His trousers were tight and short, showing his thin, bony ankles. His shoes were dejected things, dilapidated, sordidly jovial in expression. A long overcoat flapped about him, opening on a woolen sweater. He was unshaven, and his long hair was brushed straight back from his high forehead.

For a moment he looked at himself with surprised disgust. He had not known he was as bad as all that.

He dressed himself slowly and carefully, his body grateful to the comfortable, clean garments. It was as though he was shedding the degradations of the past four years with the clothes which he rolled up into a compact little bundle.

When he went down-stairs he found a young girl waiting in the drawing-room. A cloud of dusky hair was drawn back from her pure white brow, and done in a heavy coil above her white young neck. Her eyes were deep and gray and rimmed about with long dark lashes. She had a lovely deep color, a fine, full mouth and wide-cut nostrils. She was very young, and yet had the dignity which comes from responsibility and work. To Richard, she seemed as lovely as an angel and as remote. She sprang to her feet as he came in.

"Ricky!" she cried, holding out her hands.

He looked at her with polite inquiry, searching among his memories for the answer to her.

"Why, Ricky!" she said, a tremor in her voice. Don't you know me? I haven't changed so much as that, have I? I'm Dorothy!"

He tried to be cordial. "Dorothy!" he cried. He took her hands. "I didn't know—I hadn't thought—"

Then came to him a memory of a strapping tomboy, running with the dogs down Surrey lanes, long, thin legs covering the earth like a pair of callipers. And here she was, beautiful, a woman whom men would turn their heads to look at anywhere. Her beauty put him off. He was choked almost as with the coldness of disappointment.

"I recognized you," she reproached him, smiling.

"Why, you see, I haven't grown beautiful or let down my skirts," he countered. He stopped. He knew he should have said more. He had a sick sense of failing her. This was Dorothy, he told himself, the sharer of his boyhood, his faithful vassal in those old days. The current of friendship between them had never failed-until now. He was conscious that he had been writing always, to a long-legged girl whose nose was too big for her thin face, whose loosely curling hair was always falling in disorder around her eyes, a little girl who was always finding some pretext for breaking into a run. Never had he been writing to a beautiful, grave young woman.

A silence had fallen between them. She was scrutinizing him, trying to familiarize herself with him. And as he had stared at Hummer in that remote and vague way, so he stared at Dorothy.

"We have waited so for you, Ricky," she said. "I've been perched on your door-step, a fixture, ever since we got word that you were coming. We thought you'd come sooner."

"I was in Berlin ten days," he said. He stopped again. There was no way he could have told her about those ten days in Berlin. "One had," he explained, lamely, "to get used to being out in the world again, after where-we'd been, you know. I was afraid of crossing the street at first. I'd forgotten wheels and horses and things like that."

He stopped again. He felt his face flush painfully. Every now and then there would sweep over him a composite memory of those four years, which brought with it a feeling of degradation. He walked up and down the room, agitated and nervous.

"When did you learn for the first time that you were going to get away?" she prompted.

"The newspapers first. There were talks of serious riots at Hamburg."

"Newspapers?" she wondered. "I thought you weren't allowed them."

"We got them, thirty marks apiece. Six of us in each stall, five stalls to a paper. We paid fifty pfennigs apiece and each stall would read the paper for an hour—we had a reader."

"How do you mean," she asked, "six to a stall?"

He stared at her with a little impatience. "That's how we lived," he explained, "six of us, just like animals, you know—six of us to a box-stall."

He hated to have to tell about it. Memories of those degrading propinquities of life crowded about him, and yet that was all that he had to tell. Already that life was so remote, and had so little relation to reality, that it was as though it were plunging back one's mind into memories of the nightmare of delirium. She was waiting for him to go on. Her face lifted up, and there was on it an expression of eagerness which was almost as of innocent greed. Suddenly he realized that there was no place in her to which he could communicate his experiences, nor to any one who had gone on living in the world. The heroism and despairs of that place. Its monstrous loves and hates. The anguished waiting. The terrible patience of men-that fidelity to trivial occupation with which they fought to keep their sanity and self-respect.

"Go on and tell me about it, Ricky," she urged, "if you feel like it, I mean."

How can you tell people about fighting for self-respect and for sanity? That's what life had resolved itself into. Forever all the life's mean details gnawing at the foundations of your self-respect—dirt and inaction and brutality and promiscuity of life. All the enemies of dignity massed together to assail the frail spirit of man-and she asked him to tell her about it!

"What happened to Bonfield," she prompted him. "You used to write about Bonfield."

"Bonfield died," said Ricky.

"I'm sorry," she cried.

"I was glad when Bonfield died!" Ricky explained in a matter-of-fact voice. "It was a great relief. He'd gotten to be an awful nuisance."

"Why, Ricky!" she cried, shocked.

This irritated him. She wanted to know about it. Now she could have it, so he threw at her, but in a tone of level matter-of-factness.

"You get to hate them so when you live with them like that. Everything about them—the way they undress and the noises they make and the way they clean their teeth—that you plan how you could kill them, and the only reason you don't kill them is that you'd get caught, and you know that they're planning all the time how they'd like to kill you. I hadn't spoken to Bonfield for six months before he was taken sick; then I had to take care of him, and I tell you it was a relief when he died."

He knew that he was alienating her, covering himself with an armor of strangeness.

He turned the subject abruptly. "I told you we learned about the revolution first by the papers. Trouble in Hamburg, trouble in Bremen; then they said the revolution had been put down and next we saw the sailors swarming on the trains, inside and out, waving red flags." His thin face flushed again. "We couldn't believe it. We thought the troops in Berlin would arrest them. They had signs, 'Brothers, don't shoot!' " He stopped abruptly. "It seems already as if it never could have happened-those four years."

"Oh, Ricky," she cried, "it's so wonderful to have you back at last!"

For a moment they were together. In a moment they had bridged the distance that separated them, then life went flat again. He tried to keep the current of precious sympathy, but he couldn't, and she after a moment rose abruptly.

"I'll see you soon. I'll see you a great deal," she promised him, and hurried away. Ricky stared after her, wondering if he had only fancied that tears stood in her eyes.

The days passed by filled up with visits from eager, compassionate relatives. At the end of the day Ricky felt as though he had been wrung dry. How eager they were for stories of horrors! How full of energy they seemed! So to refresh himself he would go to Dorothy's, and once there would find no words, so for a while they would sit together miserably trying to grope toward each other, but not knowing how. He had learned in prison one thing, and that was how to isolate himself from his fellows through sheer force of pride. And now out of prison his habit of isolation had followed him. He walked through life, the shadowy walls of remoteness around him. It followed him to Dorothy's. It was always with him.

This troubled him, but there was something else that troubled him more and he had no name for it. It was a vague discomfort, like the knowledge that one was going to be ill, the fore-warnings of pain. He wouldn't recognize its meaning. It was like shutting out a sullen day by keeping the shade down. Suddenly one day his father snapped it out, and it was as though Ricky were blinded with a stab of light.

"I suppose," his father remarked, "you have been considering what you want to do!"

Now he knew what had disturbed him as he walked around the seething London streets, where everybody was hurrying so, as though to keep an appointment with opportunity itself. Where everybody seemed to have some object in life; yes, and aims and desires and friends and memories, and he alone had none.

To do something in the world you need preparation, and he had had four years' preparation living in a box-stall. There flashed before his mind his five companions. Dungley, who had been fat, who would have been prattling eternally about his stomach-ache, but that he was afraid of Richard, who had learned to throw at him, with a terrible young arrogance that had menace in it, "Shut up and give us a rest!" This was the sort of thing that he knew—how to make a sick man stop whimpering, or a garrulous one afraid to speak to him. So he answered his father:

"I haven't any plans. There isn't anything that I know about."

"When you were at Ruhleben didn't you plan for the future?" pursued his father. He was a big man, heavy, ponderous, who had never had the knack of drawing Ricky out. He puffed now as though dragging a heavy load.

"I only planned about getting out. I'm no good," he burst out. "I haven't learned anything!"

"Don't be morbid, my boy," said his father, ponderously.

Ricky didn't reply. He wanted to scream at his father, who stood there so complacent.

"Morbid? Morbid? Of course I'm morbid! Life's morbid! You live in a box-stall for four years and think and think about the fellows out there being shot—dying, fellows like you-and you penned up with a lot of prisoners until your thoughts drip blood. Life's been normal, hasn't it? Life's been calm!" If he could only make any one understand even for a minute. Then that desire passed like a warm tide of life, and the stale annoyance of Ruhleben enveloped him. The walls of the box-stall rose about him and shut him off.

He met his father's words with dutiful convention and went out into the hot, anonymous crowds of the streets with a vague hope that some of his adventurous imaginings of Ruhleben might come true.

Girls and women—how much he had thought about them at Ruhleben! There had been times that queer thoughts had beaten against the walls of his brain like dark birds, days when in the background of his mind were strange imageries—grotesque, unspeakable—as though in him lived the spirit of the men who had invented the carvings on the temples of India. He could not bear to have his spirit so invaded. It was as though by living like brutes, old and forgotten brutishness came stealthily forth. All the hot imaginings of antiquity pressed around him.

He had taken then to studying German grammar, to studying anything. "Keeping his mind occupied" was no mere phrase with Ricky; it was the necessity imposed on him by sanity. So in this endeavor all the thoughts of Europe surged through his mind. He read-he read-and always there was the recurring speculation about women.

Now here he was out on London streets and England's women pouring past him. He hadn't remembered them as so lovely. It was an ever-recurring surprise to him. There were a great many women in uniform. Why, what with the conductresses, half the women of England seemed in uniform. How smart they were and brisk, and how informed with purpose-and how remote from Ricky.

He could hardly talk to Hummer—he had failed miserably with Dorothy—and these handsome, ruddy, purposeful girls—the box-stall cut him off from even casual speech with them.

Ricky walked down Piccadilly past the Circus, moving without volition, as though borne on the bosom of the crowd. He got to Charing Cross and stood for a while watching all the wilful youth of the Empire flow past him. The air seemed filled with their laughter. All the sons of England went streaming past London's gray and ancient magnificence. It was darker than Ricky remembered it, and more splendid. It hadn't shrunk as some things did. Rather, it had grown. Now all the youth of the English peoples was loosed in a boiling torrent down London streets, and its grave imperial splendors formed only an unnoticed back-drop against which life was played. Australians with their brims tucked up, young, keen-faced d'Artagnans coursing down the streets, chasing amusement; New-Zealanders in their wide hats with their ribbon; Canadians, Scotchmen, and the regiments of England—you read them on their shoulders—Yorkshire, Lancashire; New South Wales, South Africa, American troops, American sailors—they swarmed everywhere. "Eating up the place" was their own term for it.

Ricky seemed to himself to be an atom removed by centuries of emptiness from the experience of this hot, gay youth that flooded and surged, and boiled through the streets.

There was still in the air a hint of the madness of armistice. One felt everything went, that the old restraints were down. You could see it in the way that the girls talked to the men and the men joked them back, and the casual acquaintances they formed in the twilights. Evidently it was the custom. The girls came flooding out from the munitions up the Strand, up Charing Cross, up Piccadilly, out for a good time.

What an England! With what insolence of youth they enjoyed themselves, as though they said to the venerable stones of the city:

"Others like us helped to build you, and we have defended you, We have come from the ends of the earth to do it. Look at us—the youth of England, of the colonies, of Canada, and of America. And so, while we remain, your streets and your pleasures belong to us."

So they streamed past Ricky like scarlet banners. They streamed past him as though keeping time to the music of drum-beats. How powerful it was, and how careless, this youth that had faced death for four years, this youth that had been snatched from death and now ran in a riot of life down London streets.

He drifted along in the crowd, feeling useless and empty. They swanked past him—groups of Scotchmen, swinging their skirts above their bare knees; Americans, solid, and walking with direction; now a New Zealand boy, searching in the crowd for a girl to speak to. Suddenly three young girls going abreast barred Ricky's way, laughing.

"Where are you off to?" one said.

"What will you give us to let you pass?" said another.

"Name and address?" asked a third, politely. Ricky couldn't make them out. They were nicely dressed, neatly booted, and wore pert little hats, and had faces that were at the same time bold and innocent and young. He stood before them namelessly embarrassed. He would have given his soul for a natural gesture. Who were they? To him it was mystery. The spectacle of the munition girls enjoying themselves was since his day. This very episode plumbed a gulf between his experience and the world he now was called to live in.

"Are you a deaf mute, dearie?" asked the prettiest one, who wore a little velvet Tam over one ear.

"Shrapnel took his tongue at Mons," another announced. They laughed immoderately, one of them doubling herself up in the abandon of her mirth. They were indecorous and shameless, and yet their gaiety had no vice in it. He stood there. Words wouldn't come to him. There were none. He snatched at them, tried to drag them out of the well of his embarrassment. What fun it would have been to run off with these youngsters. Who cared who they were?

"'E's a deef mute," said one.

"'E's a dead mute," said the other.

"'E's a dead un. Good-by, dead un!" they called, and sped down the street, trailing out cruel laughter behind them that stung Ricky like the lash of a whip. He could have cried with anger. The little scene, so unexpected and so meaningless, had plunged itself deep into some citadel of his self-respect. He drifted into an archway and stood there, feeling that now the barrier between him and the fierce, pulsing life before him was complete.

The bitter waters of defeat had now gotten as high as Ricky's heart. There came to him a certainty that he would always be like this, that he would always be a shadow at the feast of life, that he would never be able to take hold again of work or love or adventure. There was no one in all the world to whom he wanted to speak. There was nothing in all the world he wanted to do. He only wanted one single thing again, and that was to be able to turn back the hand of time four years and be back with his mother.

He wanted to see his mother. He didn't want her alive again now, because if he met her now, perhaps it would be the same as it was with his father and Hummer—and with Dorothy. But he wanted to go back. He wanted to be Ricky instead of this nameless shadow.

He drifted up Piccadilly again, turned down St. James's Street and along Pall Mall. It was quieter there. Rows of silent clubs looked down upon one, and as he walked along a feeling of revolt came over him.

"Why should I go on?" he asked himself. He had had no part in any of this—no part in the work, no part in the victory. Why should he fit himself now at this late day for a life from which he had been so completely divorced?

"Why should I go on?" he asked himself. He stopped in front of the door of one of the dark and solemnly august buildings, and then heard his own voice saying again, "Why should I go on?" He walked along, quickening his steps angrily at the thought that he had been betrayed into speaking aloud the barren miseries of his heart.

"There is no reason for going on"—he answered himself. There was not in all the world a person who needed him or who could even possibly need him. Service—all the rest of England knew it, those rioting girls and boys in uniform, his contemporaries now marching down the streets the victorious owners of England. And Ricky, who had only the cold walls of his lonely pride—and no memory of any service ever—turned his face resolutely away from this world in which he had no part or parcel. As though sucked down on some dark river of doubt and desolation, he found himself by the Thames.

He had no plan. He did not need despair to well up in a sudden flood to carry him over the brink. He could go now and look at death and think about it and get up to-morrow, or say to himself:

"My appointment with death is for half past seven to-night." That didn't matter, either. The whole business wasn't emotional enough. It was just that he definitely didn't care for this complicated business of living, and there didn't seem any sense or use in it. He had lived with just one idea in his mind so long—it was to get out. And now he carried the invisible walls of his prison about him. He was tired of them.

He walked over a bridge and stood looking at the dark water and at the lights reflected in it. And presently a soldier stopped near him. They looked at each other with suspicious eyes, like wary animals. Ricky felt the other was an intruder. He had come here to be familiar with the kind face of death. The English soldiers owned England. They might leave him by himself now. The soldier moved slowly toward him. He seemed about Ricky's age, and as he passed under the light Ricky saw that across his temple and down the side of his face was a crimson scar. He was evidently waiting to be spoken to. He seemed humble and embarrassed. There was about him something of an animal begging mutely to be taken notice of.

"It's quiet by the Thames," Ricky threw to him. If the boy would neither go away or speak, he could say something himself.

"Yes," he answered, with an oddly eager inflection. He hesitated, then he said: "You're lucky to be discharged so quick. I wish I was."

"What would you do?" asked Ricky.

"I'd get away from London, first off. Lots of the lads like it. I was in hospital a good while. I'd like to get away."

"Why?" Ricky wondered to himself. Perhaps this boy roamed London streets unable to speak to people or to take part in the great festival which was forever there in progress. "When you got away, what would you do?" Ricky asked.

"I don't rightly know. The older men—it's easy for them—but when you haven't a trade—" He spoke with difficulty. "What are you doing with yourself, now that you're through?" he asked.

"I've been in prison four years," Ricky blurted out.

"Were you so?" There was an inflection of pity in the other boy's voice. There was silence between them.

"I used to be quite mad to get to London," the boy volunteered, "and now I'm here I want to get on, but I don't know where to." His voice was puzzled. He was searching, in some blind way, for sympathy and understanding. "This takin' hold again worries a chap," he explained, in his helpless voice. "You won't know yourself what you're doing, will you?"

"No," said Ricky. "Four years in prison doesn't give you a trade."

"Nor four years at war. It's easier for the older ones," he repeated. "I had a pal-he was an aviator—and when he came home he blew his brains out. Do you know what worried him? He couldn't get up mornings, so he saw he was going to be a burden to his family and thought he'd rather 'go West.' " He looked down into the dark water. "Sounds dotty," he said, "but a chap can understand—" He let his voice trail off. And then suddenly Ricky understood, too. This other boy had come to him for sympathy and for help. In his halting fashion he was pleading with Ricky to help him back on his feet again. He came to him asking for the key to the door of normal existence.

"How did you take hold of life again? You're in civilian clothes. What did you do? How did you get at it? How do chaps like us get back in again?" was what he was asking. For the people who had gone on living in the real world couldn't help him. They didn't know about it. They talked about going to work with intolerable briskness, and about what you wanted to do, as if it was as simple as ordering a meal from a bill of fare. And this boy understood about it. He had been separated from life and come out on that dark bridge, perhaps, as Ricky had come. They looked at each other.

"What do you think about that chap, the aviator?"

"He was a fool," said Ricky, promptly. "He should have waited."

"Would it have done any good?"

"Why, of course," said Ricky. He was proud that conviction sounded in his voice. He had acted. He had come up to an emergency. "It's getting on," said Ricky. "Let's have a bite. Shall we?"

The other followed Ricky with dog-like obedience, frankly glad to let someone else lead him. They walked along, finding comfort together, two atoms lost in the world's immensity. They talked with diffidence, forever skirting the subject that was next their hearts, which was how to take hold now of that terrible and perplexing thing called Life.

They said good-by to each other after dinner and Ricky went away comforted. He knew that he wasn't an outcast in the world, and that the world was full of boys perplexed like himself, and he felt that he had the answer as to what to do. The answer was that one must go on. Time helped one. He had told the boy that and the boy believed him.

Then, walking on London streets, he had a strange vision of the world. It appeared to him like a great shining globe spinning about, and it had a hard, transparent surface, and within this surface were all those people who were part of life, all those people who had their place in life's complex affairs; while on the outside, swarming over the hard, shining surface, unable to get in, were the boys whom war had disinherited, the maimed ones and those who were sick. There was a great company of them, young and old-men whose place in the world had been wiped out while they fought, men who came home to find their families had become strangers. There were blind men and the mutilated, and there was this army of boys like the one with whom he had talked, to whom war had given no trade, and there were boys whose only knowledge of life was a box-stall. And all of these swarmed over the shining surface of the globe, trying and trying to get in-back to those within.

It was a great discovery. His heart suddenly went out to all those lonely ones. He wanted to cry out to them: "Wait! You'll find your way in. You're not alone."

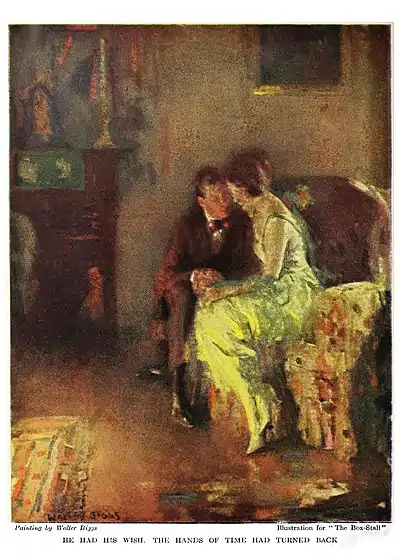

Hope bloomed green in Ricky's heart as he walked along. Then Dorothy came into his mind as though she had entered a room where he was. It was the first time that he had thought of her without feeling how intolerably he was separated from her. He imagined himself going to her, being able at last to talk instead of shouting at her over great distances, as he had before. He felt as if he must find her now, as though the clue which led one back to life was in her hand. He had told the boy time helped. He wanted her to reassure him. He wanted her to know. He hurried to her house, filled with dread that she might not be home, because he had to see her. He had to tell her his discovery. He had to ask her for this clue to life which it seemed to him she held in her hand, and he felt he couldn't wait, and that life somehow would have failed him again if she were not home. But life did not fail him. He found Dorothy in the drawing-room. She was dressed for the evening and her arms gleamed like silver. There was a little shining fillet of silver in her hair and dress of young green, and as she came toward him her very loveliness made her formidable and remote as when he had first seen her.

He found himself saying, tonelessly: "You are going out. I mustn't keep you."

"I'm not going for ever so long," she answered. "I won't go at all, Ricky, if you will stay. I'm so awfully glad to have you come."

This work is in the public domain in the United States because it was published before January 1, 1927.

The author died in 1966, so this work is also in the public domain in countries and areas where the copyright term is the author's life plus 50 years or less. This work may also be in the public domain in countries and areas with longer native copyright terms that apply the rule of the shorter term to foreign works.