THE MASTER-MAID

ONCE upon a time there was a king who had many sons. I do not exactly know how many there were, but the youngest of them could not stay quietly at home, and was determined to go out into the world and try his luck, and after a long time the King was forced to give him leave to go. When he had travelled about for several days, he came to a giant’s house, and hired himself to the giant as a servant. In the morning the giant had to go out to pasture his goats, and as he was leaving the house he told the King’s son that he must clean out the stable. ‘And after you have done that,’ he said, ‘you need not do any more work to-day, for you have come to a kind master, and that you shall find. But what I set you to do must be done both well and thoroughly, and you must on no account go into any of the rooms which lead out of the room in which you slept last night. If you do, I will take your life.’

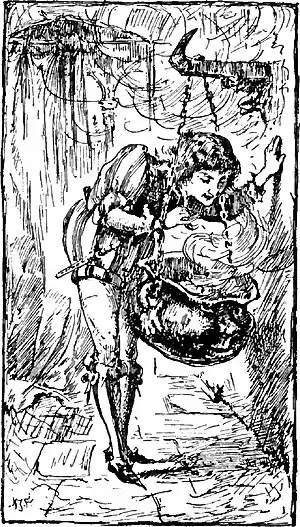

‘Well to be sure, he is an easy master!’ said the Prince to himself as he walked up and down the room humming and singing, for he thought there would be plenty of time left to clean out the stable; ‘but it would be amusing to steal a glance into his other rooms as well,’ thought the Prince, ‘for there must be something that he is afraid of my seeing, as I am not allowed to enter them.’ So he went into the first room. A cauldron was hanging from the walls; it was boiling, but the Prince could see no fire under it. ‘I wonder what is inside it,’ he thought, and dipped a lock of his hair in, and the hair became just as if it were all made of copper. ‘That’s a nice kind of soup. If anyone were to taste that his throat would be gilded,’ said the youth, and then he went into the next chamber. There, too, a cauldron was hanging from the wall, bubbling and boiling, but there was no fire under this either. ‘I will just try what this is like too,’ said the Prince, thrusting another lock of his hair into it, and it came out silvered over. ‘Such costly soup is not to be had in my father’s palace,’ said the Prince; ‘but everything depends on how it tastes,’ and then he went into the third room.  There, too, a cauldron was hanging from the wall, boiling, exactly the same as in the two other rooms, and the Prince took pleasure in trying this also, so he dipped a lock of hair in, and it came out so brightly gilded that it shone again. ‘Some talk about going from bad to worse,’ said the Prince; ‘but this is better and better. If he boils gold here, what can he boil in there?’ He was determined to see, and went through the door into the fourth room. No cauldron was to be seen there, but on a bench someone was seated who was like a king’s daughter, but, whosoever she was, she was so beautiful that never in the Prince’s life had he seen her equal.

There, too, a cauldron was hanging from the wall, boiling, exactly the same as in the two other rooms, and the Prince took pleasure in trying this also, so he dipped a lock of hair in, and it came out so brightly gilded that it shone again. ‘Some talk about going from bad to worse,’ said the Prince; ‘but this is better and better. If he boils gold here, what can he boil in there?’ He was determined to see, and went through the door into the fourth room. No cauldron was to be seen there, but on a bench someone was seated who was like a king’s daughter, but, whosoever she was, she was so beautiful that never in the Prince’s life had he seen her equal.

‘Oh! in heaven’s name what are you doing here?’ said she who sat upon the bench.

‘I took the place of servant here yesterday,’ said the Prince.

‘May you soon have a better place, if you have come to serve here!’ said she.

‘Oh! but I think I have got a kind master,’ said the Prince. ‘He has not given me hard work to do to-day. When I have cleaned out the stable I shall be done.’

‘Yes, but how will you be able to do that?’ she asked again. ‘If you clean it out as other people do, ten pitchforksful will come in for every one you throw out. But I will teach you how to do it: you must turn your pitchfork upside down, and work with the handle, and then all will fly out of its own accord.’

‘Yes, I will attend to that,’ said the Prince, and stayed sitting where he was the whole day, for it was soon settled between them that they would marry each other, he and the King’s daughter; so the first day of his service with the giant did not seem long to him. But when evening was drawing near she said that it would now be better for him to clean out the stable before the giant came home. When he got there he had a fancy to try if what she had said were true, so he began to work in the same way that he had seen the stable-boys doing in his father’s stables, but he soon saw that he must give up that, for when he had worked a very short time he had scarcely room left to stand. So he did what the Princess had taught him, turned the pitchfork round, and worked with the handle, and in the twinkling of an eye the stable was as clean as if it had been scoured. When he had done that, he went back again into the room in which the giant had given him leave to stay, and there he walked backwards and forwards on the floor, and began to hum and to sing.

Then came the giant home with the goats. ‘Have you cleaned the stable?’ asked the giant.

‘Yes, now it is clean and sweet, master,’ said the King’s son.

‘I shall see about that,’ said the giant, and went round to the stable, but it was just as the Prince had said.

‘You have certainly been talking to my Master-maid, for you never got that out of your own head,’ said the giant.

‘Master-maid! What kind of a thing is that, master?’ said the Prince, making himself look as stupid as an ass; ‘I should like to see that.’

‘Well, you will see her quite soon enough,’ said the giant.

On the second morning the giant had again to go out with his goats, so he told the Prince that on that day he was to fetch home his horse, which was out on the mountain-side, and when he had done that he might rest himself for the remainder of the day, ‘for you have come to a kind master, and that you shall find,’ said the giant once more. ‘But do not go into any of the rooms that I spoke of yesterday, or I will wring your head off,’ said he, and then went away with his flock of goats.

‘Yes, indeed, you are a kind master,’ said the Prince; ‘but I will go in and talk to the Master-maid again; perhaps before long she may like better to be mine than yours.’

So he went to her. Then she asked him what he had to do that day.

‘Oh! not very dangerous work, I fancy,’ said the King’s son. ‘I have only to go up the mountain-side after his horse.’

‘Well, how do you mean to set about it?’ asked the Mastermaid.

‘Oh! there is no great art in riding a horse home,’ said the King’s son. ‘I think I must have ridden friskier horses before now.’

‘Yes, but it is not so easy a thing as you think to ride the horse home,’ said the Master-maid; ‘but I will teach you what to do. When you go near it, fire will burst out of its nostrils like flames from a pine torch: but be very careful, and take the bridle which is hanging by the door there, and fling the bit straight into its jaws, and then it will become so tame that you will be able to do what you like with it.’ He said he would bear this in mind, and then he again sat in there the whole day by the Master-maid, and they chatted and talked of one thing and another, but the first thing and the last now was, how happy and delightful it would be if they could but marry each other, and get safely away from the giant; and the Prince would have forgotten both the mountain-side and the horse if the Master-maid had not reminded him of them as evening drew near, and said that now it would be better if he went to fetch the horse before the giant came. So he did this, and took the bridle which was hanging on a crook, and strode up the mountain-side, and it was not long before he met with the horse, and fire and red flames streamed forth out of its nostrils. But the youth carefully watched his opportunity, and just as it was rushing at him with open jaws he threw the bit straight into its mouth, and the horse stood as quiet as a young lamb, and there was no difficulty at all in getting it home to the stable. Then the Prince went back into his room again, and began to hum and to sing.

Towards evening the giant came home. ‘Have you fetched the horse back from the mountain-side?’ he asked.

‘That I have, master; it was an amusing horse to ride, but I rode him straight home, and put him in the stable too,’ said the Prince.

‘I will see about that,’ said the giant, and went out to the stable, but the horse was standing there just as the Prince had said. ‘You have certainly been talking with my Master-maid, for you never got that out of your own head,’ said the giant again.

‘Yesterday, master, you talked about this Master-maid, and today you are talking about her; ah! heaven bless you, master, why will you not show me the thing? for it would be a real pleasure to me to see it,’ said the Prince, who again pretended to be silly and stupid.

‘Oh! you will see her quite soon enough,’ said the giant.

On the morning of the third day the giant again had to go into the wood with the goats. ‘To-day you must go underground and fetch my taxes,’ he said to the Prince. ‘When you have done this, you may rest for the remainder of the day, for you shall see what an easy master you have come to,’ and then he went away.

‘Well, however easy a master you may be, you set me very hard work to do,’ thought the Prince; ‘but I will see if I cannot find your Master-maid; you say she is yours, but for all that she may be able to tell me what to do now,’ and he went to her. So, when the Master-maid asked him what the giant had set him to do that day, he told her that he was to go underground and get the taxes.

‘And how will you set about that?’ said the Master-maid.

‘Oh! you must tell me how to do it,’ said the Prince, ‘for I have never yet been underground, and even if I knew the way I do not know how much I am to demand.’

‘Oh! yes, I will soon tell you that; you must go to the rock there under the mountain-ridge, and take the club that is there, and knock on the rocky wall,’ said the Master-maid. ‘Then someone will come out who will sparkle with fire: you shall tell him your errand, and when he asks you how much you want to have you are to say: “As much as I can carry.”’

‘Yes, I will keep that in mind,’ said he, and then he sat there with the Master-maid the whole day, until night drew near, and he would gladly have stayed there till now if the Master-maid had not reminded him that it was time to be off to fetch the taxes before the giant came.

So he set out on his way, and did exactly what the Master-maid had told him. He went to the rocky wall, and took the club, and knocked on it. Then came one so full of sparks that they flew both out of his eyes and his nose. ‘What do you want?’ said he.

‘I was to come here for the giant, and demand the tax for him,’ said the King’s son.

‘How much are you to have then?’ said the other.

‘I ask for no more than I am able to carry with me,’ said the Prince.

‘It is well for you that you have not asked for a horse-load,’ said he who had come out of the rock. ‘But now come in with me.’

This the Prince did, and what a quantity of gold and silver he saw! It was lying inside the mountain like heaps of stones in a waste place, and he got a load that was as large as he was able to carry, and with that he went his way. So in the evening, when the giant came home with the goats, the Prince went into the chamber and hummed and sang again as he had done on the other two evenings.

‘Have you been for the tax?’ said the giant.

‘Yes, that I have, master,’ said the Prince.

‘Where have you put it then?’ said the giant again.

‘The bag of gold is standing there on the bench,’ said the Prince.

‘I will see about that,’ said the giant, and went away to the bench, but the bag was standing there, and it was so full that gold and silver dropped out when the giant untied the string.

‘You have certainly been talking with my Master-maid!’ said the giant, ‘and if you have I will wring your neck.’

‘Master-maid?’ said the Prince; ‘yesterday my master talked about this Master-maid, and to-day he is talking about her again, and the first day of all it was talk of the same kind. I do wish I could see the thing myself,’ said he.

‘Yes, yes, wait till to-morrow,’ said the giant, ‘and then I myself will take you to her.’

‘Ah! master, I thank you—but you are only mocking me,’ said the King’s son.

Next day the giant took him to the Master-maid. ‘Now you shall kill him, and boil him in the great big cauldron you know of, and when you have got the broth ready give me a call,’ said the giant; then he lay down on the bench to sleep, and almost immediately began to snore so that it sounded like thunder among the hills.

So the Master-maid took a knife, and cut the Prince’s little fingers, and dropped three drops of blood upon a wooden stool; then she took all the old rags, and shoe-soles, and all the rubbish she could lay hands on, and put them in the cauldron; and then she filled a chest with gold dust, and a lump of salt, and a water-flask which was hanging by the door, and she also took with her a golden apple, and two gold chickens; and then she and the Prince went away with all the speed they could, and when they had gone a little way they came to the sea, and then they sailed, but where they got the ship from I have never been able to learn.

Now, when the giant had slept a good long time, he began to stretch himself on the bench on which he was lying. ‘Will it soon boil?’ said he.

‘It is just beginning,’ said the first drop of blood on the stool.

So the giant lay down to sleep again, and slept for a long, long time. Then he began to move about a little again. ‘Will it soon be ready now?’ said he, but he did not look up this time any more than he had done the first time, for he was still half asleep.

‘Half done!’ said the second drop of blood, and the giant believed it was the Master-maid again, and turned himself on the bench, and lay down to sleep once more. When he had slept again for many hours, he began to move and stretch himself. ‘Is it not done yet?’ said he.

‘It is quite ready,’ said the third drop of blood. Then the giant began to sit up, and rub his eyes, but he could not see who it was who had spoken to him, so he asked for the Master-maid, and called her. But there was no one to give him an answer.

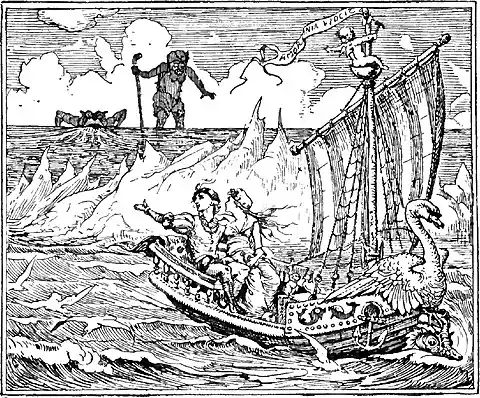

‘Ah! well, she has just stolen out for a little,’ thought the giant, and he took a spoon, and went off to the cauldron to have a taste; but there was nothing in it but shoe-soles, and rags, and such trumpery as that, and all was boiled up together, so that he could not tell whether it was porridge or milk pottage. When he saw this, he understood what had happened, and fell into such a rage that he hardly knew what he was doing. Away he went after the prince and the Master-maid, so fast that the wind whistled behind him, and it was not long before he came to the water, but he could not get over it. ‘Well, well, I will soon find a cure for that: I have only to call my river-sucker,’ said the giant, and he did call him. So his river-sucker came and lay down, and drank one, two, three draughts, and with that the water in the sea fell so low that the giant saw the Master-maid and the Prince out on the sea in their ship. ‘Now you must throw out the lump of salt,’ said the Mastermaid, and the Prince did so, and it grew up into such a great high mountain right across the sea that the giant could not come over it, and the river-sucker could not drink any more water. ‘Well, well, I will soon find a cure for that,’ said the giant, so he called to his hill-borer to come and bore through the mountain so that the river-sucker might be able to drink up the water again. But just as the hole was made, and the river-sucker was beginning to drink, the Master-maid told the Prince to throw one or two drops out of the flask, and when he did this the sea instantly became full of water again, and before the river-sucker could take one drink they reached the land and were in safety. So they determined to go home to the Prince’s father, but the Prince would on no account permit the Master-maid to walk there, for he thought that it was unbecoming either for her or for him to go on foot.

‘Wait here the least little bit of time, while I go home for the seven horses which stand in my father’s stable,’ said he; ‘it is not far off, and I shall not be long away, but I will not let my betrothed bride go on foot to the palace.’

‘Oh! no, do not go, for if you go home to the King’s palace you will forget me, I foresee that.’

‘How could I forget you? We have suffered so much evil together, and love each other so much,’ said the Prince; and he insisted on going home for the coach with the seven horses, and she was to wait for him there, by the sea-shore. So at last the Master-maid had to yield, for he was so absolutely determined to do it. ‘But when you get there you must not even give yourself time to greet anyone, but go straight into the stable, and take the horses, and put them in the coach, and drive back as quickly as you can. For they will all come round about you; but you must behave just as if you did not see them, and on no account must you taste anything, for if you do it will cause great misery both to you and to me,’ said she; and this he promised.

But when he got home to the King’s palace one of his brothers was just going to be married, and the bride and all her kith and kin had come to the palace; so they all thronged round him, and questioned him about this and that, and wanted him to go in with them; but he behaved as if he did not see them, and went straight to the stable, and got out the horses and began to harness them. When they saw that they could not by any means prevail on him to go in with them, they came out to him with meat and drink, and the best of everything that they had prepared for the wedding; but the Prince refused to touch anything, and would do nothing but put the horses in as quickly as he could. At last, however, the bride’s sister rolled an apple across the yard to him, and said: ‘As you won't eat anything else, you may like to take a bite of that, for you must be both hungry and thirsty after your long journey.’ And he took up the apple and bit a piece out of it. But no sooner had he got the piece of apple in his mouth than he forgot the Master-maid and that he was to go back in the coach to fetch her.

‘I think I must be mad! what do I want with this coach and horses?’ said he; and then he put the horses back into the stable, and went into the King’s palace, and there it was settled that he should marry the bride’s sister, who had rolled the apple to him.

The Master-maid sat by the sea-shore for a long, long time, waiting for the Prince, but no Prince came. So she went away, and when she had walked a short distance she came to a little hut which stood all alone in a small wood, hard by the King’s palace. She entered it and asked if she might be allowed to stay there. The hut belonged to an old crone, who was also an ill-tempered and malicious troll. At first she would not let the Master-maid remain with her; but at last, after a long time, by means of good words and good payment, she obtained leave. But the hut was as dirty and black inside as a pigstye, so the Master-maid said that she would smarten it up a little, that it might look a little more like what other people’s houses looked inside. The old crone did not like this either. She scowled, and was very cross, but the Mastermaid did not trouble herself about that. She took out her chest of gold, and flung a handful of it or so into the fire, and the gold boiled up and poured out over the whole of the hut, until every part of it both inside and out was gilded. But when the gold began to bubble up the old hag grew so terrified that she fled away as if the Evil One himself were pursuing her, and she did not remember to stoop down as she went through the doorway, and so she split her head and died. Next morning the sheriff came travelling by there. He was greatly astonished when he saw the gold hut shining and glittering there in the copse, and he was still more astonished when he went in and caught sight of the beautiful young maiden who was sitting there; he fell in love with her at once, and straightway on the spot he begged her, both prettily and kindly, to marry him.

‘Well, but have you a great deal of money?’ said the Mastermaid.

‘Oh! yes; so far as that is concerned, I am not ill off,’ said the sheriff. So now he had to go home to get the money, and in the evening he came back, bringing with him a bag with two bushels in it, which he set down on the bench. Well, as he had such a fine lot of money, the Master-maid said she would have him, so they sat down to talk.

But scarcely had they sat down together before the Master-maid wanted to jump up again. ‘I have forgotten to see to the fire,’ she said.

‘Why should you jump up to do that?’ said the sheriff; ‘I will do that!’ So he jumped up, and went to the chimney in one bound.

‘Just tell me when you have got hold of the shovel,’ said the Master-maid.

‘Well, I have hold of it now,’ said the sheriff.

‘Then may you hold the shovel, and the shovel you, and pour red-hot coals over you, till day dawns,’ said the Master-maid. ‘So the sheriff had to stand there the whole night and pour red-hot coals over himself, and, no matter how much he cried and begged and entreated, the red-hot coals did not grow the colder for that. When the day began to dawn, and he had power to throw down the shovel, he did not stay long where he was, but ran away as fast as he possibly could; and everyone who met him stared and looked after him, for he was flying as if he were mad, and he could not have looked worse if he had been both flayed and tanned, and everyone wondered where he had been, but for very shame he would tell nothing.

The next day the attorney came riding by the place where the Master-maid dwelt. He saw how brightly the hut shone and gleamed through the wood, and he too went into it to see who lived there, and when he entered and saw the beautiful young maiden he fell even more in love with her than the sheriff had done, and began to woo her at once. So the Master-maid asked him, as she had asked the sheriff, if he had a great deal of money, and the attorney said he was not ill off for that, and would at once go home to get it; and at night he came with a great big sack of money—this time it was a four-bushel sack—and set it on the bench by the Master-maid. So she promised to have him, and he sat down on the bench by her to arrange about it, but suddenly she said that she had forgotten to lock the door of the porch that night, and must do it.

‘Why should you do that?’ said the attorney; ‘sit still, I will do it.’

So he was on his feet in a moment, and out in the porch.

‘Tell me when you have got hold of the door-latch,’ said the Master-maid.

‘I have hold of it now,’ cried the attorney.

‘Then may you hold the door, and the door you, and may you go between wall and wall till day dawns.’

What a dance the attorney had that night! He had never had such a waltz before, and he never wished to have such a dance again. Sometimes he was in front of the door, and sometimes the door was in front of him, and it went from one side of the porch to the other, till the attorney was well-nigh beaten to death. At first he began to abuse the Master-maid, and then to beg and pray, but the door did not care for anything but keeping him where he was till break of day.

As soon as the door let go its hold of him, off went the attorney. He forgot who ought to be paid off for what he had suffered, he forgot both his sack of money and his wooing, for he was so afraid lest the house-door should come dancing after him. Everyone who met him stared and looked after him, for he was flying like a madman, and he could not have looked worse if a herd of rams had been butting at him all night long.

On the third day the bailiff came by, and he too saw the gold house in the little wood, and he too felt that he must go and see who lived there; and when he caught sight of the Master-maid he became so much in love with her that he wooed her almost before he greeted her.

The Master-maid answered him as she had answered the other two, that if he had a great deal of money she would have him. ‘So far as that is concerned, I am not ill off,’ said the bailiff; so he was at once told to go home and fetch it, and this he did. At night he came back, and he had a still larger sack of money with him than the attorney had brought; it must have been at least six bushels, and he set it down on the bench. So it was settled that he was to have the Master-maid. But hardly had they sat down together before she said that she had forgotten to bring in the calf, and must go out to put it in the byre.

‘No, indeed, you shall not do that,’ said the bailiff; ‘I am the one to do that.’ And, big and fat as he was, he went out as briskly as a boy,

‘Tell me when you have got hold of the calf’s tail,’ said the Master-maid.

‘I have hold of it now,’ cried the bailiff.

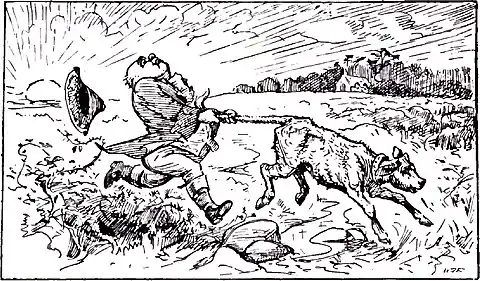

‘Then may you hold the calf’s tail, and the calf’s tail hold you, and may you go round the world together till day dawns!’ said the Master-maid. So the bailiff had to bestir himself, for the calf went over rough and smooth, over hill and dale, and, the more the bailiff cried and screamed, the faster the calf went. When daylight began to appear, the bailiff was half dead; and so glad was he to leave loose of the calf’s tail that he forgot the sack of money and all else.

He walked now slowly—more slowly than the sheriff and the attorney had done, but, the slower he went, the more time had everyone to stare and look at him; and they used it too, and no one can imagine how tired out and ragged he looked after his dance with the calf.

On the following day the wedding was to take place in the King’s palace, and the elder brother was to drive to church with his bride, and the brother who had been with the giant with her sister. But when they had seated themselves in the coach and were about to drive off from the palace one of the trace-pins broke, and, though they made one, two, and three to put in its place, that did not help them, for each broke in turn, no matter what kind of wood they used to make them of. This went on for a long time, and they could not get away from the palace, so they were all in great trouble. Then the sheriff said (for he too had been bidden to the wedding at Court): ‘Yonder away in the thicket dwells a maiden, and if you can but get her to lend you the handle of the shovel that she uses to make up her fire I know very well that it will hold fast.’ So they sent off a messenger to the thicket, and begged so prettily that they might have the loan of her shovel-handle of which the sheriff had spoken that they were not refused; so now they had a trace-pin which would not snap in two.

But all at once, just as they were starting, the bottom of the coach fell in pieces. They made a new bottom as fast as they could, but, no matter how they nailed it together, or what kind of wood they used, no sooner had they got the new bottom into the coach and were about to drive off than it broke again, so that they were still worse off than when they had broken the trace-pin. Then the attorney said, for he too was at the wedding in the palace: ‘Away there in the thicket dwells a maiden, and if you could but get her to lend you one-half of her porch-door I am certain that it will hold together.’ So they again sent a messenger to the thicket, and begged so prettily for the loan of the gilded porch-door of which the attorney had told them that they got it at once. They were just setting out again, but now the horses were not able to draw the coach. They had six horses already, and now they put in eight, and then ten, and then twelve, but the more they put in, and the more the coachman whipped them, the less good it did; and the coach never stirred from the spot. It was already beginning to be late in the day, and to church they must and would go, so everyone who was in the palace was in a state of great distress. Then the bailiff spoke up and said: ‘Out there in the gilded cottage in the thicket dwells a girl, and if you could but get her to lend you her calf I know it could draw the coach, even if it were as heavy as a mountain.’ They all thought that it was ridiculous to be drawn to church by a calf, but there was nothing else for it but to send a messenger once more, and beg as prettily as they could, on behalf of the King, that she would let them have the loan of the calf that the bailiff had told them about. The Master-maid let them have it immediately—this time also she would not say ‘no.’

Then they harnessed the calf to see if the coach would move; and away it went, over rough and smooth, over stock and stone, so that they could scarcely breathe, and sometimes they were on the ground, and sometimes up in the air; and when they came to the church the coach began to go round and round like a spinning-wheel, and it was with the utmost difficulty and danger that they were able to get out of the coach and into the church. And when they went back again the coach went quicker still, so that most of them did not know how they got back to the palace at all.

When they had seated themselves at the table the Prince who had been in service with the giant said that he thought they ought to have invited the maiden who had lent them the shovel-handle, and the porch-deor, and the calf up to the palace, ‘for,’ said he, ‘if we had not got these three things, we should never have got away from the palace.’

The King also thought that this was both just and proper, so he sent five of his best men down to the gilded hut, to greet the maiden courteously from the King, and to beg her to be so good as to come up to the palace to dinner at mid-day.

‘Greet the King, and tell him that, if he is too good to come to me, I am too good to come to him,’ replied the Master-maid.

So the King had to go himself, and the Master-maid went with him immediately, and, as the King believed that she was more than she appeared to be, he seated her in the place of honour by the youngest bridegroom. When they had sat at table for a short time, the Master-maid took out the cock, and the hen, and the golden apple which she had brought away with her from the giant’s house, and set them on the table in front of her, and instantly the cock and the hen began to fight with each other for the golden apple.

‘Oh! look how those two there are fighting for the golden apple,’ said the King’s son.

‘Yes, and so did we two fight to get out that time when we were in the mountain,’ said the Master-maid.

So the Prince knew her again, and you may imagine how delighted he was. He ordered the troll-witch who had rolled the apple to him to be torn in pieces between four-and-twenty horses, so that not a bit of her was left, and then for the first time they began really to keep the wedding, and, weary as they were, the sheriff, the attorney, and the bailiff kept it up too.[1]

- ↑ Asbjornsen and Möe.