This work is in the public domain in the United States because it was published before January 1, 1927.

The author died in 1934, so this work is also in the public domain in countries and areas where the copyright term is the author's life plus 80 years or less. This work may also be in the public domain in countries and areas with longer native copyright terms that apply the rule of the shorter term to foreign works.

THE

BIRD WATCHER IN THE SHETLANDS

WITH SOME NOTES ON SEALS—AND DIGRESSIONS

All rights reserved

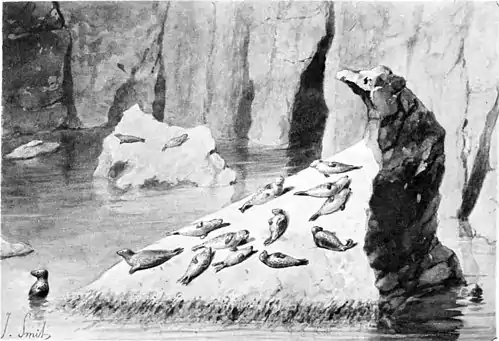

A Seal's Dormitory.

THE

BIRD WATCHER

IN THE SHETLANDS

WITH SOME NOTES ON SEALS,

—AND DIGRESSIONS

BY

WITH 10 ILLUSTRATIONS

BY

J. SMIT

LONDON: J. M. DENT & CO.

NEW YORK: E. P. DUTTON & CO.

1905

PREFACE

IN the spring of 1900 I paid my first visit to the Shetlands, and most of what I then saw is embodied in my work Bird Watching. Two years afterwards I went there again, arriving somewhat later, and it is the notes made by me during this second stay which fill the greater number of these pages. They are my journal, written from day to day, amidst the birds with whom I lived without another companion, nor did I look upon them as more than the rough material out of which I might, some day, make a book. When it came to making one, however, it struck me more and more forcibly that I was taking elaborate pains to stereotype and artificialise what was, at any rate, as it stood, an unforced utterance and natural growth. I found, in fact, that I could make it worse, but not better, so I resolved not to make it worse. Except for a few peckings, therefore, and minor interpolations—mostly having to do with the working out of ideas jotted down in the rough—I send it to press with this very negative sort of recommendation, and with only the hope added that what interested me so much will interest others also, even through the veil of my writing. Besides birds, I was lucky enough this time to have seals to watch, and I watched them hour after hour and day after day. I believe I know them better now, than I do anybody, or than anybody does me; but that is not to say much, for, as the true Russian proverb has it, "Another man's soul is darkness." But I have them in my heart for ever, and I would take them out of the Zoological Society's basins, and throw them back into the sea, if I could.

I have no doubt that these pages contain some errors of observation or inference which I am not yet aware of—but those who only glance at them may sometimes be inclined to correct me, where, later, I correct myself. It is best, I think, to let one's mistakes stand recorded against one, for mistakes have their interest, and often emphasize some truth. Honesty, too, would suffer in their suppression—and besides, if one has got in some idea or reflection that pleases one, or a piece of descriptive writing that does not seem amiss, how tiresome to have to scratch it out, merely because it is founded on a wrong apprehension!—the spire to come tumbling just for the want of a base! For these reasons, therefore—especially the last, when it applies—I have not suppressed my errors, even where I happen to know them. There they stand, if only to encourage others who may be labouring in the same field as myself—which makes one more high-minded motive.

For my digressions, etc.—for which I have been taken to task—I hope this fresh crop of them will make it apparent that they are a part of my method, or, rather, a part of myself. I have still a temperament I find—and it gives me a good deal of trouble—but as soon as I have become a nonentity, I will follow the advice given me, and write like one. I would say more if I could, but I must not promise what it is not in my power to perform.

EDMUND SELOUS