XV

APPLE-BLOSSOMS AND WHITE MUSLIN

COCO, the snow-white cockatoo, on his perch high up in the roof dormer overlooking the court, is having the time of his life. To see and hear the better, he wobbles back and forth to the end of his wooden peg, steadying himself by his black beak, and then, straightening up, unfurls his yellow celery top of a crest and, with a quick toss of his head, shrieks out his delight.

He wants to know what it is all about, and I don’t blame him. No such hurrying and scurrying has been seen in the court-yard below since the morning the players came down from Paris and turned the sixteenth-century quadrangle into a stage-setting for an old-time comedy: new gravel is being raked and sifted over the open space; men on step-ladders are trimming up the vines and setting out plants on top of the kiosks; others are giving last touches to the tulip-beds and the fresh sod along the borders, while two women are scrubbing the chairs and tables under the arbors.

As for the Inn’s inhabitants, everybody seems to have lost their wits: Pierre has gone entirely mad. When butter, or eggs, or milk, or a pint of sherry—or something he needs, or thinks he needs—is wanted, he does not wait until his under-chef can bring it from the storage-cave where they are kept—he rushes out himself, grabbing up a basket, or pitcher, or cup as he goes, and comes back on the double-quick to begin again his stirring, chopping, and basting—the roasting-spit turning merrily all the while.

Leà is even more restless. Her activities, however, are confined to clattering along the upstairs corridors, her arms full of freshly ironed clothes—skirts and things—and to the banging of chamber doors—one especially, behind which sits an old fishwoman, yellow as a dried mackerel and as stiff, helping a young girl dress.

The only one who seems to have kept his head is Lemois. His nervousness is none the less in evidence, but he gets rid of his pent-up steam in a different way. He lets the others hustle, while he stands still just inside the gate giving orders to hurrying market boys with baskets of fish; signing receipts for cases filled with poultry and early vegetables just in by the morning train from Caen; or firing instructions to his gardeners and workmen—self-contained as a ball governor on a horizontal engine and seemingly as inert, yet an index of both pressure and speed.

All this time Coco keeps up his hullabaloo, nobody paying the slightest attention. Suddenly there comes an answering cry and the cockatoo snaps his beak tight with a click and listens intently, his head on one side. It is the shriek of a siren—a long-drawn, agonizing wail that strikes the bird dumb with envy. Nearer it comes—nearer—now at the turn of the street; now just outside the gate, and in whirls Herbert’s motor, the painter beside him.

“Ah!—Lemois—the top of the morning to you and yours!” Louis’ stentorian voice rings out. “Never saw a better one come out of the skies. Out with you, Herbert. Are we the first to arrive? Here, give me that basket of grapes and box of bonbons. A magnificent run, Lemois. Left Paris at five o’clock, while the milk was going its rounds; spun through Lisieux before they were wide awake; struck the coast, and since then nothing but apple-bloom—one great pink-and-white bedquilt up hill and down dale. Glorious! I want a whole tree, full of blossoms, remember—just as I wrote you—none of your mean little chopped-off twigs, but a cart-load of branches. Let me have that old apple-tree out in the lot in front—the apples were never any good, and Mignon may as well have the blossoms as those thieving boys. Did you send word to the school children? Yes, of course you did. Oh, I tell you, Herbert, we are going to have a bully time—Paul and Virginia are not in it. Hello! Leà, you up there, you blessed old carved root of a virgin!—where’s the adorable Mignon?”

“Good-morning, Monsieur Louis—and you too, Monsieur Herbert,” came her voice in reply from the rail of the gallery above our heads. “Mignon is inside,” and she pointed to the closed door behind her. “Gaston’s mother is helping her. Madame la marquise will be here any minute, and so will Monsieur Le Blanc and everybody from Buezval. Oh!—you should see my child! You wouldn’t know her in the pretty clothes madame has sent.”

And now while Herbert is digging out from under the motor seats various packages tied with white ribbons, including the drawing he made of Leà, now richly framed, and which with the aid of the old woman he carried up the crooked stairway and deposited at a certain door, I will tell you what all this excitement is about.

Madame la marquise has had her way. Not an instantaneous and complete victory. There had been parleyings, of course, after that eventful night some months before when she had outgeneralled and then defied Lemois, and concessions had been made, both sides yielding a little; but before we separated for our homes we felt sure that the old man either had or would surrender.

“Well, let it be as you will,” he had said with a sigh; “but not now. In the spring when the apple-blossoms are in bloom—and then perhaps you may come back.”

To me, however, who had stayed on for a few days, he had, late one afternoon, poured out his whole heart. The twilight had begun to settle in the Marmouset, and the last glow of the western sky creeping through the stained-glass windows was falling upon the old Spanish leather and gold crowned saints and figures, warming them into rich harmonies, when I had stolen inside the wonderful room to take one of my last looks—an old habit of mine in a place I love. There I found him hunched up in Herbert’s chair at one corner of the fireplace, his head on his hand.

“Well, you have won your fight,” he had said in a low, measured voice, speaking into the bare chimney, his fingers still supporting his forehead. “You will take my child from me and leave me alone.”

“But she will be much happier,” I now ventured.

“Perhaps so—I cannot tell. I have seen many a bright sunrise end in a storm. But none of you have understood me. You thought it was money, and what the man could bring her, and that I objected because the boy was poor and a fisherman. What am I but a man of the people?—what is she but a peasant?—and her mother and grandmother before her. Who are we that we should try to rise above our station, making ourselves a laughing-stock? Had he been a land-owner with a thousand head of cattle it would have been the same with me. Nothing will be as it was any more. I am an old man and she is all the child I have. When she was eight years old she would come into this very room and nestle close in my lap, and I would talk to her by the hour—she and I alone, the fire lighting up the dark. And so it was when she grew up. It is only of late that she has shut herself away from me. I deserve it maybe—she must marry somebody, and I would not have it otherwise—but why must it be now? I do not blame madame la marquise. She is an enthusiastic woman whose heart often runs away with her head; but she is honest and sincere. She had only the child’s happiness in view, and she will be a mother to them both as long as she lives, as she is to many others I know.”

He had paused for a moment, I standing still beside him, and had then gone on, the words coming slowly, like the dropping of water:

“You remember Monsieur Herbert’s story, do you not, of the old mould-maker who lost his daughter, and who died in his chair, his clay masks grinning down at him from the skylight above? Well, I am he. Just as they grinned at the old mould-maker, his daughter gone, so in my loneliness will my figures grin at me.”

This had been in late October.

What the dull winter had been to him I never knew, but he had not gone back on his word, and now that the apple-blossoms were in bloom, and the orchards a blaze of glory, the wedding day, just as he had promised, had arrived!

No wonder, then, Coco is screaming at the top of his voice; no wonder the court-yard is swept by a whirlwind of flying feet; no wonder the upstairs chamber door, with Leà as guardian angel, is opened and shut every few minutes, hiding the girl behind it; and no wonder that Herbert’s impatient car, every spoke in its wheels trembling with excitement, is puffing with eagerness to make the run to the old apple-tree in the outer lot, and so on to the church, loaded to its extra tires with a carpet of blossoms for Mignon’s pretty feet.

No wonder, either, that before Herbert’s car, with Louis in charge of the blossom raid, had cleared the back gate, there had puffed in another motor—two this time—Le Blanc in one, with his friend, The Architect, beside him, the seats packed full of children, their faces scrubbed to a phenomenal cleanliness, their hair skewered with gay ribbons, all their best clothes on their backs; madame la marquise and Marc in the other, an old weather-beaten fisherman—an uncle of Gaston’s, too lame to walk—beside her, and bundled up on the back seat two lean withered fishwomen in black bombazine and close-fitting white caps—a cousin and an aunt of the groom—the first time any one of the three had ever stepped foot in a car.

As madame and her strange crew entered the court, I turned instinctively to Lemois, wondering how he would deport himself when the crucial moment arrived—and a car-load of relatives certainly seemed to express that fatality—but he was equal to the occasion.

“Ah, madame!” he said in his courtliest manner, his hand over his heart, “who else in the wide world would have thought of so kindly an act? These poor people will bless you to their dying day. And it is delightful to see you again, Monsieur Marc. You have, I know, come to help madame in her good works. As I have so often told her, she is”

“And why should I not give them pleasure, you dear Lemois? See how happy they are. And this is not half of them! No, don’t get out, mère Francine—you are all to keep on to the church and get into your seats before the village people crowd it full; and you, Auguste”—this to her chauffeur—“are to go back to Buezval for the others—they are all waiting.” Here she espied Herbert on a ladder tacking some blossoms over the doorway. “Ah!—monsieur, aren’t you very happy it has turned out so well? I caught only a glimpse of you as you dashed past a few minutes ago or I should have held you up and made you bring the balance of the old fishwomen. They are all crazy to come. Ah! but you needn’t to have come down. It is so good to see you again,” and she shook his hand heartily. “But what a morning for a wedding! Did you notice as you came along the shore road the little puff clouds skipping out to sea for very joy and hear the birds splitting their throats in song? Even my own head is getting turned with all this billing and cooing, and I warn all of you right here”—and she swept her glance over the men gathered about her, her eyes twinkling in merriment—“that you must be very careful to keep out of my way or the first thing you know one of you will be whisked off to the altar and married before you know it. And now I am going upstairs to see how my little bride gets on, if Monsieur Marc will be good enough to carry my heavy wraps inside.”

She turned, stopped for an instant attracted by something she saw through the archway of the court, and burst into a peal of ringing laughter.

“Oh!—come here quick, every one of you, and see what’s driving in! It’s Monsieur Brierley in the dearest of donkey carts. Where did you get that absurd little beast?”

“Whoa! Victor Hugo!” shouted Brierley, springing from the cart (both together wouldn’t have covered the space occupied by an upright piano). “I found him last fall, my dear madame la marquise, in a stable in Caen, kicking out the partitions, and brought him home to my Abandoned Farm by the Marsh to add a touch of hilarity to my surroundings. He wakes me every morning with his hind feet against the door of his stable and is a most engaging and delightful companion. Hello! Lemois, and—you here, Herbert! Shake!—awful glad to see you. Where’s Louis?—gone for blossoms?—just like him. I tried to get here earlier, to help you all, but Victor Hugo is peculiar and considerably set in his ways, and if I had tried to overpersuade him he might still be a mile down the road with his feet anchored in the mud.

“Take a look inside my cart, will you, Herbert? My contribution to start the young couple housekeeping”—and he pulled off a covering of clean straw—“six dozen eggs, a pair of mallards—shot them yesterday, and about the last of them this season, and no business to shoot even these—a basket of potatoes, a dozen of pear jam—in family jars—and a small keg of apple-jack—the two last, the sweet and the strong, to be eaten and drank together to keep peace in the house. No, don’t take Hugo out of the shafts, Lemois, and don’t say anything about its being meal-time, not loud enough for him to hear. When the fun is over I’m going to drive him down to madame’s garage and pack the housekeeping stuff away in Mignon’s cupboard.”

Long before noon the court-yard, as well as the archway and the kiosks and arbors, had begun to fill up, the news of the extraordinary proceedings having brought everybody ahead of time. There was the mayor, wearing his tricolor sash and insignia of office, and with him his stout, double-chinned wife in black silk and white gloves—bareheaded, except for a gold ornament that looked like a bunch of twisted hair-pins; there were the apothecary and the notary and the man who sold pottery, not forgetting the bustling, outspoken fat doctor who had sewed up Gaston’s head the time madame’s villa went sliddering toward the sea—or tried to—as well as all the great and small folk of the village who claimed the least little bit of acquaintance with any one connected with the function from Lemois down.

Why the distinguished Madame la Marquise de la Caux—to say nothing of Lemois and the equally distinguished sculptors, painters, and authors, some of whom were well known to them by reputation—should make all this fuss about a simple little serving-maid who had brought them their coffee—a waif, really, picked from between the cobbles—one like a dozen others the village over, except for her beauty—was a question no one of them had been able to answer. Was it a whim of the great lady?—for it was well known she had made the match—or was there something else behind it all? (a mystery, by the way, which they are still trying to solve; disinterested kindness being the most incomprehensible thing in the world to some people). The notary was particularly outspoken in his opinion. He even criticised the great woman herself from behind his hand to the apothecary, whose upper room he occupied. “Been much better if these people of high degree had stayed at home and let the two young people enjoy themselves in their own way. Great mistake mixing the classes.” But, then, the notary is the mouth-piece of the revolutionary party in the village and hates the aristocracy as a singed cat does the fire.

Soon there came a shout from the gallery over our heads, and we all looked up. Leà, her wrinkled face aglow with that same inner light, the rays struggling through her rusty skin, craned her head over the rail. Then came Mignon, madame close behind, pushing her veil aside so we could all see her face—the girl blushing scarlet, but too happy to do more than laugh and bow and make little dumb nods with her head, hiding her face as best she could behind Leà’s angular shoulders.

“Yes, we are all ready, and are coming down the back stairs, and will meet you at the gate,” cried madame when she had released the girl—“and it’s time to start.”

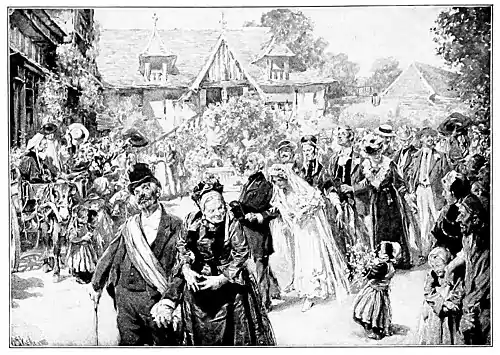

Mignon’s passage along the corridor, followed by madame and Leà and Gaston’s old mother, roused a murmur of welcome which swelled into an outburst of joyous enthusiasm as her feet touched the level of the court, and continued until she had joined Gaston and the others already formed in line for the march to the church.

And a wonderful procession it was!

First, of course, came the mayor—his worthy spouse on his left. “The State before the Church,” madame la marquise remarked with a sly twinkle, “and quite as it should be,” rabid anti-clerical as she was.

Close behind stepped Lemois in a frock-coat buttoned to his chin, his grave, thoughtful face framed in a high collar and black cravat—like an old diplomat at a court function—Mignon on his arm: Such a pretty, shrinking, timid Mignon, her lashes lifting and settling as if afraid to raise her eyes lest some one should find a chink through which they could peep into her heart.

Next came Louis escorting dear old Leà!

There was a picture for you! Had she been a duchess the rollicking young painter could not have treated her with more deference, bearing himself aloft, his chest out, handing her over the low “thank-ye-marm” at the street corner—the old woman, straight as her bent shoulders would allow, calm, self-contained, but near bursting with a joy that would drown her in tears if she gave way but an instant—and all with a quiet dignity that somehow, when you looked at her, sent a lump to your throat.

And then madame and Gaston!—she stepping free and alive, her little feet darting in and out below her rich, short gown, her eyes dancing; he swinging along beside her with that quick, alert step of the young who have always stretched their muscles to the utmost, his sun-burnt skin twice as dark from the mad rush of blood through his veins; abashed at the great honor thrust upon him, and yet with that certain poise and independence common to men who have fought and won and can fight and win again.

And last—amused, glad to lend a hand, enjoying it all to the full—Herbert, and Gaston’s poor old broken-down-with-hard-work mother—stiff, formal, scared out of her seven wits—trying to smile as she ambled along, her mouth dry, her knees shaking—the rest of us bringing up the rear—Brierley, Le Blanc, The Architect, Marc, and I walking together.

But the greatest sight was at the church—it was but a short step,—the mayor, as he reached it, bowing right and left to the throng, the sacristan pushing his way through the

First, of course, came the mayor—his worthy spouse on his lef

It was high noon now—the warm spring sun in both their faces—Mignon on Gaston’s arm. And a fine and wholesome pair they made—good to look upon, and all as it should and would oftener be if meddlesome cooks could keep their fingers out of the social broth: she in her pretty white muslin frock and veil, her head up, her eyes shining clear—she didn’t care now who saw; Gaston in his country-cut clothes (his muscles would stretch them into lines of beauty before the week was out), his new straw hat with its gay ribbon half shading his fine, strong young face; his eyes drinking in everything about him—too supremely happy to do more than walk and breathe and look.

Everything was ready for them at the Marmouset. Lemois had not been a willing ally, but having once sworn allegiance he had gone over heart and soul. The young people and their friends—as well as his own—including the exalted lady and her band of conspirators, should want for nothing at his hands.

Louis and Leà, as well as madame la marquise, were already inside the Marmouset when the bride and groom arrived. More apple-blossoms here—banks and festoons of them; the deep, winter-smoked fireplace stuffed full; loops, bunches, and spirals hanging from the rafters, the table a mass of ivory and pink, the white cloth with its dishes and viands shining through.

Mignon’s lip quivered as she passed the threshold, and all her old-time shyness returned. This was not her place! How could she sit down and be waited upon—she who had served all her life? But madame would have none of it.

“To-morrow, my child, you can do as you choose; to-day you do as I choose. You are not Mignon—you are the dear sweet bride whom we all want to honor. Besides, love has made you a princess, or Monsieur Herbert would not insist on your sitting in his own chair, which has only held the nobility and persons of high degree, and which he has wreathed in blossoms. And you will sit at the head of the table too, with Gaston right next to you.”

As grown-ups often devote themselves to amusing children—playing blind-man’s-buff, puss-in-the-corner, and Santa Claus—so did Herbert and Louis, Le Blanc, Brierley, The Architect, madame, and the others lay themselves out to entertain these simple people. Leà and Mignon, knowing the ways of gentle-folk, soon forgot their shyness, as did Gaston, and entered into the spirit of the frolic without question—but the stiff old mother, and the lame uncle, and the aunts and cousins were sore distressed, refusing more than a mouthful of food, their furtive glances wandering over the queer figures and quaint objects of the Marmouset—more marvellous than anything their eyes had ever rested on. One by one, with this and that excuse, they stole away and stood outside, their wondering eyes taking in the now quiet and satisfied Coco and the appointments of the court-yard.

Soon only our own party and Leà and the bride and groom were left, Lemois still the gracious host; madame pitching the key of the merriment, Louis joining in—on his feet one minute, proposing the health of the newly married couple; his glass filled from the contents of the rare punch-bowl entwined with blossoms, which madame had given the coterie the autumn before; paying profound and florid compliments the while to madame la marquise; the next, poking fun at Herbert and Le Blanc; having a glass of wine with Lemois and another with Gaston, who stood up while he drank in his effort to play the double rôle of servant and guest, and finally, shouting out that as this was to be the last time any one would ever get a decent cup of coffee at the Inn, owing to the cutting off in the prime of life of the high priestess of the roaster—once known as the adorable Mademoiselle Mignon—that Madame Gaston Duprè should take Lemois’ place at the small table. “And may I have the distinguished pleasure, madame”—at which the bride blushed scarlet, and meekly did as she was bid, everybody clapping their hands, including Lemois.

And it was in truth a pretty sight, one never to be forgotten: Gaston devouring her with his eyes, and the fresh young girl spreading out her white muslin frock as she settled into the chair which Louis had drawn up for her, moving closer the silver coffee-pot with her small white hands—and they were really very small and very pretty—dropping the sugar she had cracked herself into each cup—“One for you, is it, madame?”—and “Monsieur Herbert, did you say two?”—and all with a gentle, unconscious grace and girlish modesty that won our hearts anew.

The snort and chug of Le Blanc’s car, pushed close to the door, broke up the picture and scattered the party. Le Blanc would drive the bridal pair home himself—Gaston’s mother and her relations having already been whisked away in madame’s motor, with Marc beside the chauffeur to see them safely stowed inside their respective cabins.

But it was when the bride stepped into the car at the gate—or rather before she stepped into it—that the real choke came in our throats. Lemois had followed her out, standing apart, while Leà hugged and kissed her and the others had shaken her hands and said their say; Louis standing ready to throw Brierley’s two big hunting-boots after the couple instead of the time-honored slipper; Herbert holding the blossoms and the others huge handfuls of rice burglarized openly from Pierre’s kitchen.

All this time Mignon had said nothing to Lemois, nor had she looked his way. Then at last she turned, gazing wistfully at him, but he made no move. Only when her slipper touched the foot-board did he stir, coming slowly forward and looking into her eyes.

“You have been a good girl, Mignon,” he said calmly.

She thanked him shyly and waited. Suddenly he bent down, took her cheeks between his hands, kissed her tenderly on the forehead, and with bowed head walked back into the Marmouset alone.

END