ACROSS THE ATLANTIC BY WIRELESS

BY FRANCIS ARNOLD COLLINS

The first regular wireless message is sent out as the steamer slowly backs from her pier. It is timed just five minutes after sailing. The sharp crack of the sending apparatus is usually drowned by the roar of the whistle calling for a clear passage in midstream. All transatlantic steamers send to the wireless station at Sea Gate, while the coastwise steamers call up the station on top of one of the skyscrapers on lower Broadway. This is merely a formal message, but no wireless log would be complete without it. This first message is known as the “T R,” no one seems to know just why. The wireless station replies as briefly as possible, and the wireless operator shuts off.

|

|

BOY AMATEURS WITH WIRELESS OUTFITS. BOYS FREQUENTLY CATCH WIRELESS MESSAGES FROM OCEAN LINERS. | |

Business soon picks up. Before the passengers are through waving farewells, some one has usually remembered a forgotten errand ashore, or decided to send a wireless (aërogram is the word), and visitors begin to look up the wireless station. It is usually a detached house on the uppermost or sun deck, just large enough for the mysterious-looking apparatus and a bunk or two. Before the voyage is over, most of the passengers will have become very familiar with the station, for it is, after all, about the most interesting place aboard. If no messages are filed for sending, the operator picks up the shore station and clicks off the name of his ship, as, for instance, “Atlantas. Nil here” (meaning “nothing here”).

Should the operator have any messages to file, he will add the number, for example: “Atlantas 3.”

The receiving station picks this up and replies quickly. If it has no messages to send, it will reply, “O K. Nil here.”

Should there be any messages to deliver, it will reply, “O K G.” (Go ahead.)

All the way down the harbor, the great ship is in constant communication, sending and receiving belated questions and answers. The passengers, who have been calling their farewells from the ship’s side as the waters widen, are merely continuing their conversations with the shores now rapidly slipping past. Your message, meanwhile, will be delivered almost anywhere in the United States within an hour, and in near-by cities in much less time.

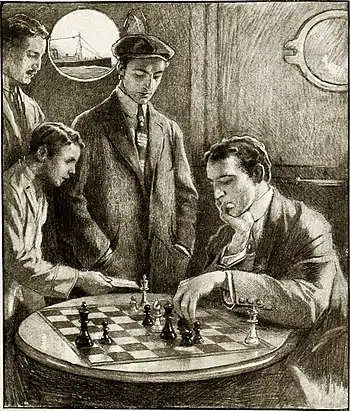

The wireless service is the last detail needed to give one the impression that the steamer is a great floating hotel. A steward comes to your room to deliver an aërogram written ashore a few minutes before, as any messenger-boy would look you up at home. If you are walking on deck, or lounging in the social-room or library, you are “paged” exactly as in a hotel. Meanwhile a bulletin, posted at the head of the main companionway or in the smoking-rooms, announces the latest weather forecast, the land station, and the various ships then in wireless communication. A little later, the daily newspaper will be published. A novel diversion of a transatlantic crossing, nowadays, is a game of chess or checkers played between passengers on two steamers hundreds of miles apart. The squares of the boards are numbered and the moves announced by simply telegraphing these numbers, when each move is made.

A CHESS GAME BY WIRELESS.

The other player may be hundreds of miles away. Each, by a wireless message, communicates his move to the other.

One of a thousand advantages of having the wireless apparatus aboard is the control it gives the captain if his ship should chance to ground down the harbor. The ship’s owners know all about the trouble almost immediately, and assistance can be rushed from the nearest point within a few minutes. There is the case, for instance, of the great liner with a thousand passengers which sailed from New York one Election Day, and stuck her nose in the mud just inside Sandy Hook. Late at night, a tug filled with newspaper men ran down the bay and came alongside. To their surprise they found the passengers in high good humor, lining the decks and shouting the latest election returns, which were being announced meanwhile in the cabin exactly as on any newspaper bulletin board.

The ship keeps its wireless connection with land through the Sea Gate station for several hours, even after the point has been left far astern. If the vessel is bound down the coast, a formal report will be sent to the Ambrose light-ship, and later to the Scotland lightship. The transatlantic liner keeps her instrument carefully attuned to the tall masts at Sea Gate until she has left them about ninety miles behind. About this time she will add “Good-by” to one of her messages, and turn to the next wireless station on her course, at Sagaponack, Long Island. Throughout the long run along the shore of North America, she will let go one wireless grasp only when another is within easy reach.

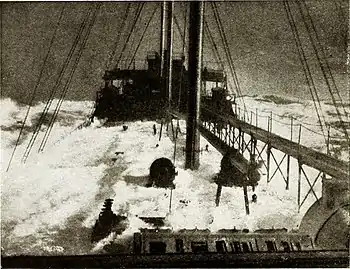

LOOKING DOWN FROM THE WIRELESS ROOM ON A FREIGHTER’S DECK DURING A HEAVY SEA.

Out here on the Atlantic, far out of sight of land, the wireless station becomes much more interesting than it is on shore or alongside the dock. At sea, this invisible link with the land is always more or less in one’s mind. The door of the wireless booth seems to lead to a bridge which spans the ocean. The wireless room has all the fascination of a newspaper bulletin board, for all the news must reach one through this channel.

It is considered a great privilege to “listen in” during an Atlantic crossing. There are very few hours, indeed, when a visitor to the wireless house, or cabin, would not be seriously in the way. If a corner of the cabin be found for you, however, and the receiving apparatus clasped to your ears, you will be amazed to find how busy the apparatus is kept. The air above New York harbor is as crowded with wireless messages as are the waters with ships. You are, besides, in easy range of many commercial stations and hundreds of amateurs. Long after the shores have disappeared from view, the buzz of wireless talk continues. There are hundreds of amateur wireless stations along the Atlantic seaboard listening to ships’ messages. It is comforting to know that if, by an accident, the powerful shore stations should fail to catch our messages, an army of alert boys are on guard.

Some four hours after your ship has passed out of Sandy Hook, or after a ninety-mile run, the operator bids the Sea Gate station good-by, and begins to feel ahead for the next station at Sagaponack, or even the one at Siasconset, on Nantucket Island. If your ear is Sensitive enough, you have probably heard her call sometime before. For a few minutes all sending and receiving is stopped while the ship throws out her name, over and over again. Soon the wireless man catches the Nantucket’s reply, and explains that he could recognize the operator’s sending among a thousand.

Then he plunges into the work of sending and receiving messages. It was the Nantucket station, he will explain to you, that first picked up the C Q D call of the ill-fated Republic, and, by its promptness, gave the rescue steamers the news in time to save all on board. The first call of a station is always listened to with a thrill of expectation.

An incessant chatter of shore talk reaches every ship, but your boat, you will find, has no time for idle gossip. But let a faint call flash from the Atlantic, and every nerve is strained to catch it. From now on, you will be constantly picking up news from the incoming steamers, and their messages are certain to be interesting. When a steamer is far out on the Atlantic and out of direct communication with the stations near New York, it is cheaper to relay messages from one steamer to another than to send to the far northern stations, and have them cable New York. In other words, the steamers scattered along the ocean lanes are used as stepping-stones to communicate with New York and Europe.

About this time you may look for news from the steamers on “the banks,” as the region along the eastern shore of Newfoundland is called. Such news is of the greatest importance, and must be carried instantly to the captain, who makes his plans accordingly. The incoming steamer reports the weather, the presence of fogs or icebergs, and their exact location. News of this kind takes precedence over everything else, and the apparatus is tuned to catch these reports, whether it gets the regular messages or not.

Your wireless operator seems to be on the friendliest possible terms with all the wireless stations. The men are constantly changing about between the ships and the shore stations. To this group of operators the world seems small indeed. The men may not meet for years, and yet, in stations thousands of miles apart, their friendship is kept alive by almost constant conversation.

When Siasconset is dropped astern, the apparatus is attuned to the lonely station at [[Cape Sable, on the bleak shores of Nova Scotia|]]. The steamer has been plowing steadily ahead for two days over the trackless ocean, but is still in almost instant communication with its last port. The wireless man will probably find time for a friendly word or two to cheer up the lonely watchers in these northern stations. The operator on one of our crossings explained that on his westward trip, a few days before, this station had been silent for as much as half an hour. There had been a slight accident to the machinery, and, in this isolated position, the wireless man must make his own repairs. Our operator understood perfectly, but he found time to ask his friend if the fishing were good, and received instantly an indignant reply.

RECEIVING A WIRELESS MESSAGE ON DECK.

After Cape Sable, the ship continues its shore messages through the wireless station at Sable Island. Our ship is far north now, and the wireless stations are well up toward the verge of the snows. If you have sailed out of New York on a hot summer’s day, it will be difficult to picture to yourself the man who is now talking to you, perhaps wrapped in heavy winter clothing, looking out on a field of ice. It is not uncommon to receive messages from the tropics and from the stations not. very far below the arctic circle at the same moment. If the operator wishes to do so, he can tune his instrument now to pick up the series of wireless stations scattered along the Labrador coast. These stations are not used by the transatlantic steamers, but work only with the vessels, sealing expeditions, etc., plying in these waters.

The good ship is now nearing the eastern-most point of North America, and at Cape Race picks up the last land station. Once more a batch of messages is received and despatched. Cape Race is not a post to be coveted. It is one of the most isolated in the world, and throughout the greater part of the year perhaps the coldest. Operators stationed here have gone blind from the glare of the sun upon unbroken icefields. In leisure hours they have some compensation in hunting wild northern game. “Yet, through the long winters, they have snatches of the news only a few minutes later than the newspaper offices in London or New York. An operator stationed here once broke the monotony of his life by chatting, with the wireless men on the ships, about the base-ball games, which were reported to him inning by inning.

Ever since the steamer left New York, the editors of her daily newspaper have been receiving the latest news and publishing it in their daily editions, exactly as in any well-equipped newspaper ashore. This news is sent out regularly from a station at Cape Cod. The news of the world, including the latest stock-exchange quotations, is boiled down to 500 words, and is sent broadcast out across the Atlantic at exactly ten o'clock every night. It is thrown out for about 1800 miles in all directions, so that any vessel between America and the middle of the ocean may catch it. When the despatch is completed, there is a pause of fifteen minutes, when it is repeated over the same enormous area, and the repetitions continue steadily until 12:30. The ships suit their own convenience, picking up the news, at any time between these hours, when they are not engaged with other messages.

When the calls from the Cape Race station grow faint and are finally cut off, our steamer ends its direct service to shore. We are now more than one third of the way across the Atlantic. Nevertheless, the ship is very rarely completely out of touch with the shore throughout the crossing. The ocean lanes are so peopled with great ships that a message can be relayed from ship to ship to the land station in an incredibly short time.

And for some hundreds of miles farther, as we go across the Atlantic—to the very middle of the ocean—the news service still follows our ship. Regularly every night at 10:30, the operator tunes his instrument to the Cape Cod station and writes down the latest news at the dictation of the operator, now more than a thousand miles away.

Half-way across the Atlantic, before the Cape Cod messages have died away, our operator catches his first wireless from Europe, flung out to welcome him from the powerful station at Poldhu, on the Cornwall coast. There is scarcely a moment on the broad Atlantic when we cannot listen to one or the other of these stations. Poldhu sends out news and the stock reports, just 500 words of it, exactly as does Cape Cod, beginning every morning at two, and repeating the messages at regular intervals until three. And so the wireless newspaper you pick up at your breakfast in any region of the Atlantic, is quite as up-to-date as the one you read at home.

Even in the middle of the ocean, there is very little rest for the wireless operators. There is scarcely an hour when our ship is not in communication with one or more vessels. On a single crossing, aboard one of the great liners, there are usually from 500 to 600 wireless messages transmitted and received. When a ship is. picked up, a notice is posted in the companionway, smoking-room, and elsewhere, announcing that messages may be sent to such a vessel up to an hour, easily calculated, when she will be out of range.

The first direct landward messages are sent to the station at Crookhaven, on the Irish coast. Land will not be sighted for many hours, but the passengers are at once busied with preparations for going ashore. There are scores of messages filed for both sides of the Atlantic, announcing a safe arrival—for under the protecting arms of the wireless one feels himself almost ashore greetings are exchanged, invitations extended, and the details of land journeys arranged.

When Crookhaven is dropped, the Liverpool steamer next. picks up the wireless station of Rosslare at Queenstown, and Seaforth at Liverpool. For the other steamers there are the Lizard, Bolt Head, Niton, and Cherbourg, passing in rapid succession. But the thrill of the ancient sea-cry of “Land ho!” has been anticipated a thousand miles offshore.

A SAMPLE LOG OF A WESTWARD VOYAGE

| Sept. | 28 | —In communication with Liverpool all day. |

| Sept. | 29 | —In communication with Crookhaven all day. |

| Sept. | 29 | —12:40 a.m., signaled Scheveningen Haven, 315 miles. |

| Sept. | 29 | —1:50 a.m., signaled Pola, Austria, 930 miles. |

| Sept. | 29 | —9: 20 p.m., signaled Scheveningen Haven, 600 miles. |

| Sept. | 30 | —12: 20 a.m., signaled St. Marie-de-la-Mer, 920 miles. |

| Sept. | 30 | —1: 11 a.m., signaled Seaforth, Liverpool, 400 miles. |

| Sept. | 30 | —2:40 a.m., signaled Scheveningen Haven, 705 miles. |

| Sept. | 30 | —10:39 p.m., signaled Seaforth, Liverpool, 800 miles. Sent messages. |

| Oct. | 1 | —3:20 a.m., signaled Seaforth, Liverpool, 890 miles. |

| Oct. | 1 | —9:30 p.m., signaled S.S. Camevonia, 1000 miles, |

| Oct. | 2 | —1:40 a.m., signaled Cape Race, 900 miles. Sent messages. |

| Oct. | 2 | —2 a.m., signaled Seaforth, Liverpool, 1250 miles. |

| Oct. | 2 | —7:45 p.m., signaled Cape Race, 550 miles. Sent messages. |

| Oct. | 3 | —In communication with Cape Race all day. |

| Oct. | 3 | —11:59 p.m., in communication with S.S. Kaiser Wilhelm II, eastbound, and remained in touch until 8:50 p.m. on Oct. 5, making over 1000 miles ahead and astern. Kaiser says, “We cannot get out of your range.” |

| Oct. | 4 | —In communication with Cape Race and Sable Island all day |

| Oct. | 5 | —In communication with Sable Island and Cape Sable all day. |

| Oct. | 6 | —In communication with Cape Sable, Siasconset, Sagaponack, Cape May, Sea Gate, all day. |

| Oct. | 7 | —In communication with Sea Gate. Docked 8 a.m. |

On October 2 the Cedric was in communication with both Cape Race and Seaforth together; the signals from both stations were very good, the total distance covered from Cape Race to Seaforth being 2190 miles.