SCOTT'S LAST EXPEDITION

CHAPTER I

THROUGH STORMY SEAS

The Final Preparations in New Zealand

The first three weeks of November have gone with such a rush that I have neglected my diary and can only patch it up from memory.

The dates seem unimportant, but throughout the period the officers and men of the ship have been unremittingly busy.

On arrival the ship was cleared of all the shore party, stores, including huts, sledges, &c. Within five days she was in dock. Bowers attacked the ship's stores, surveyed, relisted, and restowed them, saving very much space by unstowing numerous cases and stowing the contents in the lazarette. Meanwhile our good friend Miller attacked the leak and traced it to the stern. We found the false stem split, and in one case a hole bored for a long-stem through-bolt which was much too large for the bolt. Miller made the excellent job in overcoming this difficulty which I expected, and since the ship has been afloat and loaded the leak is found to be enormously reduced. The ship still leaks, but the amount of water entering is little more than one would expect in an old wooden vessel.

The stream which was visible and audible inside the stern has been entirely stopped. Without steam the leak can now be kept under with the hand pump by two daily efforts of a quarter of an hour to twenty minutes. As the ship was, and in her present heavily laden condition, it would certainly have taken three to four hours each day.

Before the ship left dock, Bowers and Wyatt were at work again in the shed with a party of stevedores, sorting and relisting the shore party stores. Everything seems to have gone without a hitch. The various gifts and purchases made in New Zealand were collected—butter, cheese, bacon, hams, some preserved meats, tongues.

Meanwhile the huts were erected on the waste ground beyond the harbour works. Everything was overhauled, sorted, and marked afresh to prevent difficulty in the South. Davies, our excellent carpenter, Forde, Abbott, and Keohane were employed in this work. The large green tent was put up and proper supports made for it.

When the ship came out of dock she presented a scene of great industry. Officers and men of the ship, with a party of stevedores, were busy storing the holds. Miller's men were building horse stalls, caulking the decks, re-securing the deck-houses, putting in bolts and various small fittings. The engine-room staff and Anderson's people on the engines; scientists were stowing their laboratories; the cook refitting his galley, and so forth—not a single spot but had its band of workers.

| Neale. | McCarthy. | ||||||||||||

| Stoker McDonald. |

Seaman McDonald. |

Horton. | Brissenden. | Parsons. | McKenzie. | Heald. | Balson. | ||||||

| Burton. | McGillon. | Anton. | Clissold. | Mather. | Davies. | ||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Skelton. | McLeod. | Bailey. | Forde. | Leese. | |||||||||

THE CREW OF THE ‘TERRA NOVA’

The men’s space, such as it is, therefore, extends from the fore hatch to the stem on the main deck.

Under the forecastle are stalls for fifteen ponies, the maximum the space would hold; the narrow irregular space in front is packed tight with fodder.

Immediately behind the forecastle bulkhead is the small booby hatch, the only entrance to the men’s mess deck in bad weather. Next comes the foremast, and between that and the fore hatch the galley and winch; on the port side of the fore hatch are stalls for four ponies — a very stout wooden structure.

Abaft the fore hatch is the ice-house. We managed to get 3 tons of ice, 162 carcases of mutton, and three carcases of beef, besides some boxes of sweetbreads and kidneys, into this space. The carcases are stowed in tiers with wooden battens between the tiers — it looks a triumph of orderly stowage, and I have great hope that it will ensure fresh mutton throughout our winter. On either side of the main hatch and close up to the ice-house are two out of our three motor sledges; the third rests across the break of the poop in a space formerly occupied by a winch.

In front of the break of the poop is a stack of petrol cases; a further stack surmounted with bales of fodder stands between the main hatch and the mainmast, and cases of petrol, paraffin, and alcohol, arranged along either gangway.

We have managed to get 405 tons of coal in bunkers and main hold, 25 tons in a space left in the fore hold, and a little over 30 tons on the upper deck.

The sacks containing this last, added to the goods already mentioned, make a really heavy deck cargo, and one is naturally anxious concerning it; but everything that can be done by lashing and securing has been done.

The appearance of confusion on deck is completed by our thirty-three dogs1 chained to stanchions and bolts on the ice-house and on the main hatch between the motor sledges.

With all these stores on board the ship still stood two inches above her load mark. The tanks are filled with compressed forage, except one, which contains 12 tons of fresh water — enough, we hope, to take us to the ice.

Forage.— I originally ordered 30 tons of compressed oaten hay from Melbourne. Oates has gradually persuaded us that this is insufficient, and our pony food weight has gone up to 45 tons, besides 3 or 4 tons for immediate use. The extra consists of 5 tons of hay, 5 or 6 tons of oil-cake, 4 or 5 tons of bran, and some crushed oats. We are not taking any corn.

We have managed to wedge in all the dog biscuits, the total weight being about 5 tons; Meares is reluctant to feed the dogs on seal, but I think we ought to do so during the winter.

We stayed with the Kinseys at their house ‘Te Han’ at Clifton. The house stands at the edge of the cliff, 400 feet above the sea, and looks far over the Christchurch plains and the long northern beach which limits it; close beneath one is the harbour bar and winding estuary of the two small rivers, the Avon and Waimakariri. Far away beyond the plains are the mountains, ever changing their aspect, and yet farther in over this northern sweep of sea can be seen in clear weather the beautiful snow-capped peaks of the Kaikouras. The scene is wholly enchanting, and such a view from some sheltered sunny corner in a garden which blazes with masses of red and golden flowers tends to feelings of inexpressible satisfaction with all things. At night we slept in this garden under peaceful clear skies; by day I was off to my office in Christchurch, then perhaps to the ship or the Island, and so home by the mountain road over the Port Hills. It is a pleasant time to remember in spite of interruptions — and it gave time for many necessary consultations with Kinsey. His interest in the expedition is wonderful, and such interest on the part of a thoroughly shrewd business man is an asset of which I have taken full advantage. Kinsey will act as my agent in Christchurch during my absence; I have given him an ordinary power of attorney, and I think have left him in possession of all facts. His kindness to us was beyond words.

The Voyage out

Saturday, November 26.—We advertised our start at 3 p.m., and at three minutes to that hour the Terra Nova pushed off from the jetty. A great mass of people assembled. K. and I lunched with a party in the New Zealand Company's ship Ruapehu. Mr. Kinsey, Ainsley, the Arthur and George Rhodes, Sir George Clifford, &c.2 K. and I went out in the ship, but left her inside the heads after passing the Cambrian, the only Naval ship present. We came home in the Harbour Tug; two other tugs followed the ship out and innumerable small boats. Ponting busy with cinematograph. We walked over the hills to Sumner. Saw the Terra Nova, a little dot to the S.E.

Monday, November 28.—Caught 8 o'clock express to Port Chalmers, Kinsey saw us off. Wilson joined train. Rhodes met us Timaru. Telegram to say Terra Nova had arrived Sunday night. Arrived Port Chalmers at 4.30. Found all well.

Tuesday, November 29.—Saw Fenwick re Central News agreement—to town. Thanked Glendenning for handsome gift, 130 grey jerseys. To Town Hall to see Mayor. Found all well on board.

We left the wharf at 2.30—bright sunshine—very gay scene. If anything more craft following us than at Lyttelton—Mrs. Wilson, Mrs. Evans, and K. left at Heads and back in Harbour Tug. Other tugs followed farther with Volunteer Reserve Gunboat—all left about 4.30. Pennell 'swung' the ship for compass adjustment, then 'away.'

Evening—Loom of land and Cape Saunders Light blinking.

Wednesday, November 30.—Noon 110 miles. Light breeze from northward all day, freshening towards nightfall and turning to N.W. Bright sunshine. Ship pitching with south-westerly swell. All in good spirits except one or two sick.

We are away, sliding easily and smoothly through the water, but burning coal—8 tons in 24 hours reported 8 p.m.

Thursday, December 1.—The month opens well on the whole. During the night the wind increased; we worked up to 8, to 9, and to 9·5 knots. Stiff wind from N.W. and confused sea. Awoke to much motion.

The ship a queer and not altogether cheerful sight under the circumstances.

Below one knows all space is packed as tight as human skill can devise—and on deck! Under the forecastle fifteen ponies close side by side, seven one side, eight the other, heads together and groom between—swaying, swaying continually to the plunging, irregular motion.

One takes a look through a hole in the bulkhead and sees a row of heads with sad, patient eyes come swinging up together from the starboard side, whilst those on the port swing back; then up come the port heads, whilst the starboard recede. It seems a terrible ordeal for these poor beasts to stand this day after day for weeks together, and indeed though they continue to feed well the strain quickly drags down their weight and condition; but nevertheless the trial cannot be gauged from human standards. There are horses which never lie down, and all horses can sleep standing; anatomically they possess a ligament in each leg which takes their weight without strain. Even our poor animals will get rest and sleep in spite of the violent motion. Some 4 or 5 tons of fodder and the ever watchful Anton take up the remainder of the forecastle space. Anton is suffering badly from sea-sickness, but last night he smoked a cigar. He smoked a little, then had an interval of evacuation, and back to his cigar whilst he rubbed his stomach and remarked to Oates 'No good'—gallant little Anton!

There are four ponies outside the forecastle and to leeward of the fore hatch, and on the whole, perhaps, with shielding tarpaulins, they have a rather better time than their comrades. Just behind the ice-house and on either side of the main hatch are two enormous packing-cases containing motor sledges, each 16 × 5 × 4; mounted as they are several inches above the deck they take a formidable amount of space. A third sledge stands across the break of the poop in the space hitherto occupied by the after winch. All these cases are covered with stout tarpaulin and lashed with heavy chain and rope lashings, so that they may be absolutely secure.

The petrol for these sledges is contained in tins and

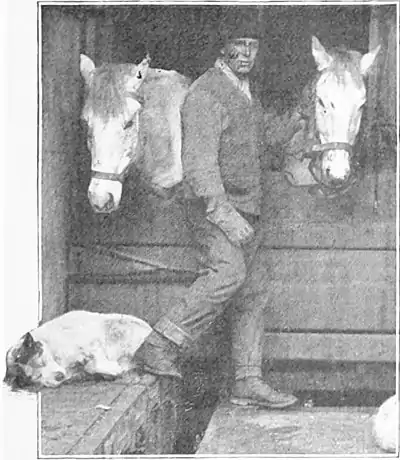

CAPTAIN OATES AND PONIES ON THE 'TERRA NOVA' drums protected in stout wooden packing-cases which are ranged across the deck immediately in front of the poop and abreast the motor sledges. The quantity is 2½ tons and the space occupied considerable.

Round and about these packing-cases, stretching from the galley forward to the wheel aft, the deck is stacked with coal bags forming our deck cargo of coal, now rapidly diminishing.

We left Port Chalmers with 462 tons of coal on board, rather a greater quantity than I had hoped for, and yet the load mark was 3 inches above the water. The ship was over 2 feet by the stern, but this will soon be remedied.

Upon the coal sacks, upon and between the motor sledges and upon the ice-house are grouped the dogs, thirty-three in all. They must perforce be chained up and they are given what shelter is afforded on deck, but their position is not enviable. The seas continually break on the weather bulwarks and scatter clouds of heavy spray over the backs of all who must venture into the waist of the ship. The dogs sit with their tails to this invading water, their coats wet and dripping. It is a pathetic attitude, deeply significant of cold and misery; occasionally some poor beast emits a long pathetic whine. The group forms a picture of wretched dejection; such a life is truly hard for these poor creatures.

We manage somehow to find a seat for everyone at our cabin table, although the wardroom contains twenty-four officers. There are generally one or two on watch, which eases matters, but it is a squash. Our meals are simple enough, but it is really remarkable to see the manner in which our two stewards, Hooper and Neald, provide for all requirements—washing up, tidying cabin, and making themselves generally useful in the cheerfullest manner.

With such a large number of hands on board, allowing nine seamen in each watch, the ship is easily worked, and Meares and Oates have their appointed assistants to help them in custody of dogs and ponies, but on such a night as the last with the prospect of dirty weather, the 'after guard' of volunteers is awake and exhibiting its delightful enthusiasm in the cause of safety and comfort—some are ready to lend a hand if there is difficulty with ponies and dogs, others in shortening or trimming sails, and others again in keeping the bunkers filled with the deck coal.

I think Priestley is the most seriously incapacitated by sea-sickness—others who might be as bad have had some experience of the ship and her movement. Ponting cannot face meals but sticks to his work; on the way to Port Chalmers I am told that he posed several groups before the cinematograph, though obliged repeatedly to retire to the ship's side. Yesterday he was developing plates with the developing dish in one hand and an ordinary basin in the other!

We have run 190 miles to-day: a good start, but inconvenient in one respect—we have been making for Campbell Island, but early this morning it became evident that our rapid progress would bring us to the Island in the middle of the night, instead of to-morrow, as I had anticipated. The delay of waiting for daylight would Page:Scott's Last Expedition, Volume 1.djvu/51 Page:Scott's Last Expedition, Volume 1.djvu/53 prevent themselves being washed overboard, and with coal bags and loose cases washing about, there was every risk of such hold being torn away.

'No sooner was some semblance of order restored than some exceptionally heavy wave would tear away the lashing and the work had to be done all over again.'

The night wore on, the sea and wind ever rising, and the ship ever plunging more distractedly; we shortened sail to main topsail and staysail, stopped engines and hove to, but to little purpose. Tales of ponies down came frequently from forward, where Oates and Atkinson laboured through the entire night. Worse was to follow, much worse—a report from the engine-room that the pumps had choked and the water risen over the gratings.

From this moment, about 4 a.m., the engine-room became the centre of interest. The water gained in spite of every effort. Lashly, to his neck in rushing water, stuck gamely to the work of clearing suctions. For a time, with donkey engine and bilge pump sucking, it looked as though the water would be got under; but the hope was short-lived: five minutes of pumping invariably led to the same result—a general choking of the pumps.

The outlook appeared grim. The amount of water which was being made, with the ship so roughly handled, was most uncertain. We knew that normally the ship was not making much water, but we also knew that a considerable part of the water washing over the upper deck must be finding its way below; the decks were leaking in streams. The ship was very deeply laden; Page:Scott's Last Expedition, Volume 1.djvu/55 Page:Scott's Last Expedition, Volume 1.djvu/57 Page:Scott's Last Expedition, Volume 1.djvu/58 Page:Scott's Last Expedition, Volume 1.djvu/59 Page:Scott's Last Expedition, Volume 1.djvu/60 especially those under the forecastle. We had thought the ponies on the port side to be pretty safe, but two of them seem tome to be groggy, and I doubt if they could stand more heavy weather without a spell of rest. I pray there may be no more gales. We should be nearing the limits of the westerlies, but one cannot be sure for at least two days. There is still a swell from the S.W., though it is not nearly so heavy as yesterday, but I devoutly wish it would vanish altogether. So much depends on fine weather. December ought to be a fine month in the Ross Sea; it always has been, and just now conditions point to fine weather. Well, we must be prepared for anything, but I'm anxious, anxious about these animals of ours.

The dogs have quite recovered since the fine weather—they are quite in good form again.

Our deck cargo is getting reduced; all the coal is off the upper deck and the petrol is re-stored in better fashion; as far as that is concerned we should not mind another blow. Campbell and Bowers have been untiring in getting things straight on deck.

The idea of making our station Cape Crozier has again come on the tapis. There would be many advantages: the ease of getting there at an early date, the fact that none of the autumn or summer parties could be cut off, the fact that the main Barrier could be reached without crossing crevasses and that the track to the Pole would be due south from the first:—the mild condition and absence of blizzards at the penguin rookery, the opportunity of studying the Emperor penguin incubation, and the new interest of the geology of Terror, besides minor facilities, such as the getting of ice, stones for shelters, &c. The disadvantages mainly consist in the possible difficulty of landing stores—a swell would make things very unpleasant, and might possibly prevent the landing of the horses and motors. Then again it would be certain that some distance of bare rock would have to be traversed before a good snow surface was reached from the hut, and possibly a climb of 300 or 400 feet would intervene. Again, it might be difficult to handle the ship whilst stores were being landed, owing to current, bergs, and floe ice. It remains to be seen, but the prospect is certainly alluring. At a pinch we could land the ponies in McMurdo Sound and let them walk round.

The sun is shining brightly this afternoon, everything is drying, and I think the swell continues to subside.

Tuesday, December 6.—Lat. 59° 7′. Long. 177° 51′ E. Made good S. 17 E. 153; 457′ to Circle. The promise of yesterday has been fulfilled, the swell has continued to subside, and this afternoon we go so steadily that we have much comfort. I am truly thankful mainly for the sake of the ponies; poor things, they look thin and scraggy enough, but generally brighter and fitter. There is no doubt the forecastle is a bad place for them, but in any case some must have gone there. The four midship ponies, which were expected to be subject to the worst conditions, have had a much better time than their fellows. A few ponies have swollen legs, but all are feeding well. The wind failed in the morning watch and later a faint breeze came from the eastward; the barometer has been Page:Scott's Last Expedition, Volume 1.djvu/63 Page:Scott's Last Expedition, Volume 1.djvu/65 Page:Scott's Last Expedition, Volume 1.djvu/66 Page:Scott's Last Expedition, Volume 1.djvu/67 Page:Scott's Last Expedition, Volume 1.djvu/68 Page:Scott's Last Expedition, Volume 1.djvu/69 Page:Scott's Last Expedition, Volume 1.djvu/71 Page:Scott's Last Expedition, Volume 1.djvu/72 Page:Scott's Last Expedition, Volume 1.djvu/74 Page:Scott's Last Expedition, Volume 1.djvu/75 Wilson shot a number of Antarctic petrel and snowy petrel. Nelson got some crustaceans and other beasts with a vertical tow net, and got a water sample and temperatures at 400 metres. The water was warmer at that depth. About 1.30 we proceeded at first through fairly easy pack, then in amongst very heavy old floes grouped about a big berg; we shot out of this and made a detour, getting easier going; but though the floes were less formidable as we proceeded south, the pack grew thicker. I noticed large floes of comparatively thin ice very sodden and easily split; these are similar to some we went through in the Discovery, but tougher by a month.

At three we stopped and shot four crab-eater seals; to-night we had the livers for dinner—they were excellent.

To-night we are in very close pack—it is doubtful if it is worth pushing on, but an arch of clear sky which has shown to the southward all day makes me think that there must be clearer water in that direction; perhaps only some 20 miles away—but 20 miles is much under present conditions. As I came below to bed at 11 p.m. Bruce was slogging away, making fair progress, but now and again brought up altogether. I noticed the ice was becoming much smoother and thinner, with occasional signs of pressure, between which the ice was very thin.

'We had been very carefully into all the evidence of former voyages to pick the best meridian to go south on, and I thought and still think that the evidence points to the 178 W. as the best. We entered the pack more or less on this meridian, and have been rewarded by encountering worse conditions than any ship has had before—worse, in fact, than I imagined would have been possible on any other meridian of those from which we could have chosen.

'To understand the difficulty of the position you must appreciate what the pack is and how little is known of its movements.

'The pack in this part of the world consists (1) of the ice which has formed over the sea on the fringe of the Antarctic continent during the last winter; (2) of very heavy old ice floes which have broken out of bays and inlets during the previous summer, but have not had time to get north before the winter set in; (3) of comparatively heavy ice formed over the Ross Sea early in the last winter; and (4) of comparatively thin ice which has formed over parts of the Ross Sea in middle or towards the end of the last winter.

'Undoubtedly throughout the winter all ice-sheets move and twist, tear apart and press up into ridges, and thousands of bergs charge through these sheets, raising hummocks and lines of pressure and mixing things up; then of course where such rents are made in the winter the sea freezes again, forming a newer and thinner sheet.

'With the coming of summer the northern edge of the sheet decays and the heavy ocean swell penetrates it, gradually breaking it into smaller and smaller fragments. Then the whole body moves to the north and the swell of the Ross Sea attacks the southern edge of the pack.

'This makes it clear why at the northern and southern limits the pieces or ice-floes are comparatively small, whilst in the middle the floes may be two or three miles across; and why the pack may and does consist of various natures of ice-floes in extraordinary confusion.

'Further it will be understood why the belt grows narrower and the floes thinner and smaller as the summer advances.

'We know that where thick pack may be found early in January, open water and a clear sea may be found in February, and broadly that the later the date the easier the chance of getting through.

'A ship going through the pack must either break through the floes, push them aside, or go round them, observing that she cannot push floes which are more than 200 or 300 yards across.

'Whether a ship can get through or not depends on the thickness and nature of the ice, the size of the floes and the closeness with which they arc packed together, as well as on her own power.

'The situation of the main bodies of pack and the closeness with which the floes are packed depend almost entirely on the prevailing winds. One cannot tell what winds have prevailed before one's arrival; therefore one cannot know much about the situation or density.

'Within limits the density is changing from day to day and even from hour to hour; such changes depend on the wind, but it may not necessarily be a local wind, so that at times they seem almost mysterious. One sees the floes pressing closely against one another at a given time, and an hour or two afterwards a gap of a foot or more may be seen between each.

'When the floes are pressed together it is difficult and sometimes impossible to force a way through, but when there is release of pressure the sum of many little gaps allows one to take a zigzag path.'