CHAPTER XI

THE LOVE-NIGHT

It was quite dark in the brougham. Sylvia released her lover’s hands and reached down to the floor of the carriage. Templar heard a click and suddenly experienced the descending-lift sensation.

“It’s all right, I tell you,” said Sylvia, her hands on his arms; “we’re just going down.”

They were. Very slowly and gently, as if it were the most natural thing in the world, the whole of the inside of the motor began to sink through the floor.

It was an ingenious arrangement, as Templar perceived later. Once in the garage, the pressure of a spring released the catch of a trap-door, which fell down at the side of what appeared to be a motor pit. Then the floor of this pit rose to meet the underside of the brougham. Another lever controlled and removed two steel rods which supported the carriage in place, and a third lever, worked from within the brougham, started the little lift on its way. They went down into darkness, and stopped with a jerk.

“Open the door,” said Sylvia, “or shall I? Can you feel the handle? Now get out.”

He got out, onto a smooth floor, and her hands came fluttering to him through the dark. They stood together outside the motor brougham.

“Stand well back,” she said, and something moved in the darkness. It was the inside of the brougham returning to its natural place in the garage above. They heard it come into position with a soft click.

“Now,” she said, “it’s all safe, and we can turn on the light. Let me.”

Her touch on the electric switch brought the light round them. He looked up at the gleam of the steel shaft that stood up from floor to ceiling of the narrow passage in which he found himself.

“How beautifully simple,” he said. “So that was how you vanished the night that I saw you home? That’s a confession, Sandra—I tried to find out where you lived long before I met you on the river.”

“Yes,” she said. “Forrester told me. I was horribly frightened at the time. Come, let’s get out of this place. It always seems to me like a crypt. I believe it’s haunted.”

It was rather like a crypt; its roof, except for the square space in which the lift worked, was of old, dark brick, with grey-green stone groining and pillars.

“What is it?” he asked, as they went. Both experienced the need to assure themselves that the solid earth still went round in the orthodox way, the need which comes to us all after great crises of life—which makes us shrink at first from vital explanations and enlightenments and talk about the weather or the Government—anything trivial rather than about that which has thrilled our souls to the very centres of life.

“It’s an underground passage.”

“Well, yes,” said he, and they laughed.

“There used to be a monastery here—it’s part of it. The old Duke of Pentland found it when he made our house. He was always fond of underground, you know—and he kept it. He made our house, too—mind your head.”

They passed through a low arch into a kitchen, a quite ordinary kitchen; then up a flight of stairs and into the room of middle Victorian souvenirs, she turning up the lights as she went.

“There!” she said, dropping her wraps and looking at him, “now we’re at home—this is where I live. It’s The House With No Address.”

“I see,” he said. And did, in a measure.

“It’s a wonderful place, isn’t it? I’ll show you all over it.”

“Presently,” he said, “you ought to rest now. Can’t I ring for some wine?”

“There’s some in the cabinet,” she said, and laughed. “I hope this isn’t a dream.”

“It’s very like one,” he said, and got the wine. Tall Venice glasses were beside it in the cabinet—and food on fine china covered with fine damask.

“We’ll have supper presently,” she said, taking the glass from his hand. “You, too—we’ll drink each other’s healths.”

But he was, after all, too conventional a lover to do otherwise than drink from her glass, ostentatiously turning it so that his lips should rest where hers had been.

Then they stood an instant looking at each other.

“How quiet it is here,” he said.

“Yes,” said she.

Then there was silence again.

“Come,” he said briskly, “you must sit down and rest; and let me sit beside you and hold your hand and look at you and get used to the dream. Tell me things. Tell me all about this wonderful house, and how you found it.”

She, too, still wanted the relief of words that did not touch the truth that lay between them—the truth that had divided and did now unite.

“It was Uncle Mosenthal,” she said, and told him of their coming to town.

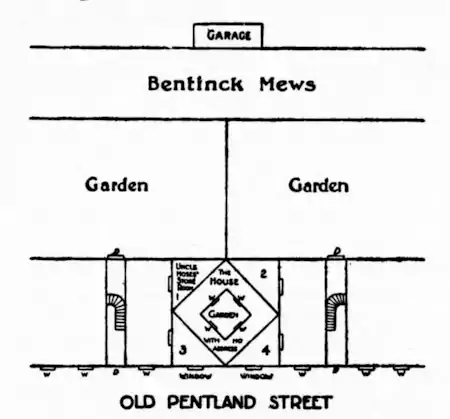

“His grandfather bought the house a long time ago. He owns the whole of this block. It was that old Duke of Pentland who built ours. He sort of dug out the insides of two of these houses and made our house in the middle, diamond shape, you know—so that nothing shows from the outside. All the windows open into the garden in the middle.

“I don’t understand in the least,” he said.

“It is difficult: I’ll draw it for you, if you’ve got a bit of paper and a pencil.”

She reached for the papier-mâché blotting-book and, his chin on her shoulder as he looked on, drew on a letter from his pocket something like this:

“I see—but surely people must know of this place—the men who mend the roofs and put up telephone wires. . . ?”

“The telephone men don’t notice the shapes of roofs, I suppose; and he has all the repairs done by workmen from his place in the country—brings them up by motor and takes them back every night—the gardener, too—and the woman who does our housework. She’s deaf and dumb and very stupid, but she works all right. Oh, it’s a wonderful scheme! No one but Uncle Mosenthal could have invented it.”

“He must be a wonderful man.”

“He is. He is frightfully nice, and he’s in all sorts of things. He half owns the Theatre—and all sorts of companies and things. He calls himself a house-agent. . . but I know the King has sent for him—for some secret reason or other, and he had to start for Germany last night. He’s a wonderful person—and kind! The world’s full of people he’s been kind to. That deaf and dumb woman, he saved her life in a fire—his own self.”

“And your chauffeur—how did you square him?”

“Oh, he was one of the village boys I used to know at home, and he went into a motor works, and when Uncle Moses had invented the lift and motor scheme, I thought of him. He made the motor. And he put in the electric light. He is much too fond of me to give away our secret. . . .”

“But I don’t understand how it is that a full account of all this isn’t in the illustrated papers every week. The Hydraulic Power people must be interested in that lift.”

“It isn’t the Hydraulic: It’s the American elevator. There’s a tank on the roof of the house the garage is under, and.——”

“I see.”

“In the wicked Lord Pentland’s time there was just a trap door under the stable and a ladder down. They kept straw there to hide the trap door. It has been such fun. And I always feel so safe here. You see, Uncle Moses is next door—I’ve only got to press that button if anything went wrong—he’d be here in half a minute.”

“But he’s in Germany. . . ?”

“Ah! but when he’s at home!”

“The rooms in the houses next door must be a funny shape.”

“Oh, he has the cornery bits boarded off. . . calls them store-rooms. That makes it look all right, and of course all the storerooms have windows on the street.—And—oh!”

He had caught her in his arms—almost roughly.

“Why are we wasting our time like this?” he said, holding her. “You could have told me all this when the others were here. Where are they? When will they come in?”

“It’s all right,” she said soothingly; “they’re at The Wood House. Uncle Moses sends his motor down with us sometimes after the performance. At first I thought I’d give up The Wood House altogether—and then I couldn’t bear to, after all. But I haven’t cared to go since. . . . But it’s good for them, and I insist on their going.”

“When will they get back?”

“Oh—in two or three days.”

“Do you mean,” he said slowly, “that there’s no one else in this house but you. . . but us? That there won’t be?”

“No,” she said, “not anyone else. It’s home, dear—only you and me.”

Through her thin bodice he could feel the sweet warmth of her body. Her breast heaved quietly against his breast. She put up her arms to his neck and drew his lips to hers. They stood so, till it seemed to him that the beating of his heart was so loud that she must hear it, even through the self-righteous tick of the carriage-clock on the mantel-piece.

They were alone—they were alone in that quiet house, safe shut in—no one else anywhere, in any of the rooms. They were betrothed lovers; in a few days—tomorrow if he chose—they would be man and wife. And her arms were round his neck, their faces touched, and against his breast her breast rose and fell.

“Sandra,” he said hoarsely, “Sandra, Sandra.”

“My love,” she answered. “Oh, my love! I have prayed God to give you back to me—and now He has. I didn’t think He would. I didn’t really believe in prayer. Oh! my love—I believe in it now.”

He kissed her lips, her forehead, undid the clasp of her arms about his neck and kissed her hands.

“Dear—dear, dear one,” he said, “this is our magic palace. We aren’t man and woman: you’re an enchanted princess, and I’m your slave.”

“You’re my prince,” she said, and drew up his hands to lie under her chin.

Templar took some credit to himself for being able to say, in quite a natural and hearty manner:

“Princess, your prince is at death’s-door. He has had nothing to eat since breakfast.”

You know the pretty moan of pity for your sufferings—remorse for her neglected hostess duties—resolution to ease your pangs instantly, at whatever cost to herself or the world, with which the woman who loves you receives your announcement that you are hungry? If you do not know it, you have never been whole-heartedly loved by a woman.

She flew to a drawer for napery, flew to the cabinet for food.

“There—the spoons and things are in that big inlaid box on the sofa-table. Yes, the bread here. There are some chocolates over there—in that silver box—yes. Let’s have the lily in the middle of the table. Isn’t it wonderful for us to have a table with a lily in the middle of it? We’ve always eaten out-of-doors before, sitting with our feet in wet ditches, like tramps!”

The emotion that had shaken him to the soul, had just touched hers with the tips of light fingers, almost unfelt, wholly unrealised. And it was that touch that changed her mood from desperate clinging tenderness to a wild childlike gaiety.

“The big armchair for you—that’s where the master of the house sits. The little Eugénie one for me, so that I can be a humble mouse and catch all the crumbs. Very well—one glass is enough. What a good thing we haven’t got a butler. He wouldn’t approve. When we engage our butler we’ll make it a condition that he shall always let us drink out of the same glass.”

The worst of saying you are hungry when you are not—or of telling any other lie, for that matter—is that you have to live up to it. Sandra heaped chicken on his plate—like all women, Sandra adored chicken—and it was not the chicken’s fault if it tasted to him like sawdust. But there was a satisfaction in waiting on her; and the gentle intimacy of the meal eaten together helped him in more ways than one.

They cleared the table, and the carriage clock announced with some asperity that it was one o’clock.

“Ought I to go?” he made himself say.

She opened reproachful eyes.

“Oh, no,” she said, “unless you’re frightfully tired. Do you want to go?”

His eyes answered her.

“Then don’t. Indeed, you mustn’t go. There are so many things to say.”

She curled herself in the corner of the sofa and held out a hand to him. He took it, and leaned back in the sofa’s other corner, their locked hands at long arm’s-length between them.

“You saw it in the papers?” he said.

“No—it was a letter. I’ll show it to you.”

She drew it warm from her bosom.

“How could you carry it there?” he said, without meaning to.

“It was the only safe place,” she said simply. “And it’s not from him, you know. It’s from a woman.!’

Written on cheap, dull, black-edged paper, the letter said:

13 Andover Terrace,

Stoke Newington.

“Madam,—I regret to inform you of the death of Mr. Saccage, who has lodged with me for some years. He was taken ill about ten days ago—double pneumonia—and from the first the doctor said ‘No hope.’ He suffered a great deal, but mostly in his mind. When delirious he talked constantly of you and seemed a prey to regret the way he had treated you. He exacted a promise from me to write and tell you he died repenting his sins and begging your forgiveness. Again and again he said: “And I hope she will marry at once—why should she delay an hour? I have stood in her way too long.” Of course it is none of my business, but he said over and over he would not lie quiet in his grave till you were happy and married to the gentleman of your choice. Excuse me mixing myself up in your affairs, but it is not my choice, and I am sure his words when unconscious would have touched any heart. He desired me to send you a packet of letters which I will send registered as soon as I can find them. Your photo is to be buried on his heart. He said he always loved you, though treating you so harsh on account of his jealousy and you being so cold to him. I do not pretend to understand what it is all about, but no doubt you will know.—Yours obediently, Martha Clitheroe.”

They read it together, their hands still locked on the sofa between them.

“I must be rather horrid,” she said, leaning across to rub her cheek against his shoulder, “because when I read it I couldn’t feel a bit sorry for him. I do now. Perhaps he really was fond of me.”

“I daresay he was,” said Templar grimly,; rose, and put the letter on the table. Then he sat down again in his corner. Sandra had already returned to hers.

“I suppose it’s almost as bad as murder to wish that somebody was dead. Do you know I’ve prayed he might die. That night I went home and prayed. . . and now he’s dead.. . . It isn’t really wicked, is it? Not really. You don’t know how horrible he was that night.”

She had drawn her hand from his and was twisting it with its fellow, on her knee.

“What night?” he asked, remote in his corner.

“The night after—after I’d lost you—oh, I forget—you don’t know. We haven’t told each other anything, really. I don’t want to talk about it.”

“Do you mean you’ve seen him again? Spoken to him? Allowed him to speak to you?” His face had changed—darkened; his features seemed thickened and swollen.

“I—I couldn’t help it. He would have come to the house and made a row. It was very late that night. There was a letter from him. I went out and met him. . .”

“You went out and met that man? Alone?”

“I took my little revolver—I’d gone to bed, after I came home from seeing you. I was tired, ill. . . I don’t know. And I told the others to go to bed and leave some supper for me. And it was awfully late when I went down to get it. Wasn’t it horrid of me to be hungry. But I was. And there was his letter—I had to go out and meet him!”

“Were you dressed?”

“Of course I was dressed. Why are you like this? What is it?”

“I hate to think of your being alone with that man. Go on.”

“I told him to stand where he was, and if he came near me I’d shoot him. Once he moved, and I nearly did. And I wished I could—and nobody know it. I don’t wonder you hate me. I am horrible. And then I prayed he might die.”

“Go on.”

“That’s all.”

“You haven’t told me what he wanted—what he said.”

“Oh!—horrible things. I can’t tell you.”

“You shall tell me.” He caught her wrists and held them.

“Don’t,” she said: “you frighten me.”

“Tell me, then,” he repeated, and his grasp of her wrists hurt.

“About our being married—him and me. . . and wanting. . .”

“Did he want you to go and live with him?”

“I don’t know. No. He. . . don’t make me tell you,” she said.

“Go on,” he said inexorably.

“He said if I married you he’d not interfere if I paid him.”

“Is that all?”

“Yes.” Pause. “Nearly all.”

“Go on.”

“Or that if you didn’t care about marrying me we could live together without.”

“Damn!” said he.

“Why did you make me tell you?” she said. “Yes, I’ll tell you everything. You’re hurting me—let go.”

“Go on.”

“And he threatened me and said things about actresses and dancers being all horrid about love and things. That was when I wanted to shoot him. Only they’d have found his body, and known. Yes—now you hate me. It serves me right for speaking the truth.”

“What did you say to him?”

“I told him to do what he chose, and that I wasn’t afraid of him. But I was.”

“Did he touch you?”

“I should have killed him if he had.”

“And then?”

“Then I came home—and then I worked as hard as I could—and prayed. And then he was dead. He’s dead now. And yet you go on like this. And now you don’t love me any more—I wish I was dead. I wish I’d never seen you.”

“It’s a good thing for him he’s dead,” said Templar savagely. “If I’d been there when he dared to speak to you like that, he wouldn’t have had much chance of speaking like it again.”

“Don’t let’s think of him any more,” she said. “Don’t. I can’t bear it. Don’t look like that. You frighten me. Don’t. I can’t bear it. I can’t bear any more. I’ve borne so much. You don’t really love me. You don’t know what I’ve done and suffered for you. You never will know. Ah!——”

She sprang up wildly. And he, as wildly, caught her in his arms.

“Don’t I love you?—don’t I? Don’t you understand that I can’t bear to think of his coming within a yard of you? Don’t you know what jealousy means? Don’t you know it drives me mad? How would you like me to meet another woman alone at night, in a shrubbery—a woman I was married to?”

“I should know you didn’t want to. I should trust you,” she said.

“You don’t know how I love you,” he said: “it’s like a fire in my heart to think of him. Oh, I tell you, it’s a good thing for him that he’s dead.”

“Don’t,” she said faintly, “oh, don’t! I have been brave. I can’t be brave any more. Forget him. Promise me you’ll never talk of him again to me. I shall go mad if you do. I know I shall. Promise.”

“I’ll promise anything you like,” he cried, and his anger transfused itself into passion. “You’re mine, mine, mine! Are you afraid of me now? Are you?”

“No,” she breathed, in a caress.

“You ought to be,” he said, and let her go. She did not understand him. He walked to the window and stood looking out on the dark pit at the bottom of which was, she had told him, the garden.

She followed, and laid her head against his arm.

“Ah, don’t,” she said. “We’ve been so miserable. Can’t we be happy now that we’ve got each other?”

“I ought to go,” he said dully.

“No!” she said, “no. How can I ever let you go again?” She turned her face to his, and her eyes implored.

“There!” he said hastily, and kissed her, answering her appeal.

“It’s not all right? You’re still angry?”

“No—no—I’m not angry—I’m—I’m tired.”

“Lie down,” she said; “lie down on the sofa, go to sleep. I’ll sit and hold your hand. I’m not tired.”

“We’ll sit down,” he said, “and talk of pleasant things.”

“Two,” said the carriage clock, more in sorrow than in anger.

They took, as before, the opposite ends of the sofa. But in five minutes his arm was round her neck, and she was smiling at him with lovely, innocent eyes—alluring, intolerable. He turned her face so that he could not see it.

“Why,” she said, resisting, “how pale you are—and how bright your eyes are!”

“The better to see you with,” he quoted.

“What is it—what is it? Aren’t you happy?”

“Happy?” he echoed. “There—let’s be quiet and rest.”

Her arm went round his neck, and she rested there. And so they sat, in a silence electric with his passion. In her, only a faint, not-understood longing troubled the joy of that silence—the longing to do everything for him, to be everything to him, to give him everything he wanted, to make him happy. This longing, in the breast of a woman who loves is as tinder to the spark of man’s desire—and thus are kindled the great fires that burn down cities, and lay waste happy fields.

And so they sat—he thrilled with the fierceness of the fight within him, and she clinging, yielding, and yet ignorant that there was any fight in him, any demand on her. The natural sweet tenderness of her embrace touched presently the spring of tenderness in him; his arm clasped her less closely, more kindly, and when at last she fell asleep in his arms he held her lightly, securely, fondly, cherishing her in her slumber as one holds and cherishes a sleeping child. Toward morning he, too, slept.

There are for all of us some moments that stand out forever, pure gold against the dull dust-colour of life. For him the moment of all such moments was that in which he woke to the chatter of the sparrows in the grey of the London dawn and found her in his arms.

He would not move even to lay his lips to her face—lest he should awaken her; he sat still as sleep, while the light brightened and deepened in the strange room, repainting the colours of curtain and carpet that dawn had made ash-coloured and at last, washing away with a flood of pure light the last shadows in the corners.

“Six,” said the carriage clock cheerfully, as one who bears no malice. And she smiled and woke, and smiled again.

That they could not pass the day together was a grief that they shared, as they shared their breakfast—as they meant, from now onward, to share all things.

He had promised his uncle to go round quite early. It was not an attractive prospect, but it had to be faced.

“You’ll send a wire for me to Denny at The Wood House, won’t you; he must come up at once and get me that new head modelled.”

It was delightfully domestic—to be there alone with her, to have her pour the tea, and charge him with commissions. This was how it was always to be.

“I shall go down to The Wood House to-morrow—yes, I can get the charwoman or someone to stay here if you really think I oughtn’t to be alone. But you’ll come and see me tonight. I’ll arrange with Forrester. . .”

“No,” he said, “I can’t do that. But I’ll come to Wood House to-morrow—no, not to-morrow, hang it, I can’t—Sunday, if I may. I’ll come down on Sunday afternoon.”

She found his hat, in the corner where he had thrown it, fetched him a clothes brush. He carried the tea-tray for her into the kitchen; folded the table cloth and put it away.

It was to be always like this.

“Forrester comes at eight,” she said. “Come and see the garden.”

It was a queer dark garden, in whose black mould ivy grew, and ferns, and spiky irises. There was a fountain in the middle, with a flagged pathway round it—bay trees in tubs, pink geraniums in stone vases.

“But they soon die,” she said. “We have to keep getting fresh ones. I expect there’s a Lorenzo head in each of the pots really, and that kills the flowers. They look just like it, don’t they?”

In the passage under the lift she whistled through a speaking-tube to Forrester above, giving him his orders.

“The lift’s coming now,” she said. “Goodbye! Good-bye!—till Sunday.”

There was a respectfully resentful something in Forrester’s manner as he adjusted the steel bars of the motor brougham, which forced Templar to say, quite without meaning to:

“Your mistress and I are engaged to be married.” He found it comforting to add: “She wishes to see you as soon as possible, to arrange for some woman to come and sleep in the house to-night. It is not right that she should be alone here.”

“No, sir,” said Forrester, “it isn’t.”