LITTLE BEAR'S-SON

N a certain Tzardom of the thirtieth realm, across three times nine lands, beyond the sea-ocean, there once lived an old peasant with his wife. They were honest and industrious, though they did not swim in cheese and butter. Indeed, they were very poor and moreover had no children, which was a great grief to them. In scanty seasons the peasant eked out his living by hunting wolves and bears, whose skins he marketed to buy bread.

N a certain Tzardom of the thirtieth realm, across three times nine lands, beyond the sea-ocean, there once lived an old peasant with his wife. They were honest and industrious, though they did not swim in cheese and butter. Indeed, they were very poor and moreover had no children, which was a great grief to them. In scanty seasons the peasant eked out his living by hunting wolves and bears, whose skins he marketed to buy bread.

One day he tracked a bear to its den and having killed it, he found there to his astonishment a little boy three years old, naked and sturdy, whom the bear had stolen and had been rearing like a cub. The peasant took the little boy home, called in the priest, had him baptized Ivashko Medvedko, which is to say "Little Ivan, Bear's-Son," and began to bring him up as his own.

The lad grew not by years, but by hours, as fast as if someone were dragging him upstairs, until when he was fifteen he was of a man's height and stronger than anyone in the whole countryside. He did not realize his own strength, so that before long, as he played with the other lads of the village, accidents began to happen. When he would seize a playmate by the hand it was a piece of luck if he did not pull the hand off, and arms and even heads were separated from their bodies when he was made angry.

This naturally produced much trouble, and finally his neighbors came to the old peasant and said: "Thou art our neighbor and our countryman and we have no quarrel with thee. But as for thy 'bear's-son,' he should be thrust forth from the village. We do not choose longer to have our little children maimed by his antics."

The old man was sad and sorry, for he loved the lad and knew that he was of a good heart and meant no mischief. Little Bear's-Son noticed his downcast looks and asked: "Why art thou so sad, little grandfather? Who has taken away thy happiness?"

"Ah, little grandson," said the old man, sighing heavily, "thou hast been my only comfort. Now our neighbors have determined to expel thee from the village, and what wilt thou do, and how wilt thou live?"

"Well, little grandfather," answered he, "this is truly a great misfortune, but it cannot be helped. Go thou, I pray, and buy me an iron club of twenty-five poods weight. Let me remain here but three weeks longer, to exercise and develop my body, and then I shall leave thee to make mine own way in the white world, to show myself and to be seen." The old man went and bought the heavy iron club, loaded it in a cart and brought it home, and with it Little Bear's-Son began each day to exercise.

Now near by was a green meadow on which stood three fir-trees; the first was fifteen reaches around, the second twenty, and the third twenty-five. When the first week was ended he went to the meadow, seized the first fir-tree and putting forth all his strength, pulled it over. He went home and exercised with his iron club a second week, and at the end of that time he went to the meadow, seized the second fir-tree, bent it down to the ground and broke it into two pieces. He went home and exercised with his iron club yet a third week, and going to the meadow, he seized the third fir-tree and with a single jerk tore it up by the roots. So mighty was his strength that the earth shook, the forest moaned, the sea-ocean began to boil and the fir-tree was reduced to powder. "Now," said Little Bear's-Son, "I am so strong that I fear not even a witch," and bidding farewell, with tears, to the old man and the old woman, he thrust his iron club into his girdle and went whither his eyes looked.

Whether he wandered a long way or a short way, he came at length to a river three versts wide. On its bank knelt a giant, as tall as a birch sapling, and as thick as a hayrick, with his mouth stretched wide in the water, catching fish with his mustache. When he caught one, he kindled a fire on his tongue, roasted and swallowed it.

"Health to thee, giant," said Little Bear's-Son. "Who art thou?"

"Health to thee," answered the other. "My name is Usynia.[1] Whither goest thou?"

"Whither my eyes look," replied Little Bear's-Son. "Wilt thou come with me? It is merrier with companionship. Thou art of a goodly size and shouldst be a man of strength."

"As for that," said the giant, "my strength is nothing. For a really strong man, they say thou must go to him who is named Ivashko Medvedko."

"That is my name," said Little Bear's-Son.

"Then will I go with thee right willingly," said the other, and he left off his fishing and they journeyed on together.

They traveled for a day, when they came to a valley in which a giant four yards tall was at work. He was carrying earth thither, a whole hill at a time, and mending the roads with it.

"Health to thee," said Little Bear's-Son. "What art thou called?"

"Health to thee," replied the giant. "My name is Gorynia.[2] Whither doth God lead you?"

"Whither our eyes look," said Little Bear's-Son. "Thou art a strong man, I see. But why dost thou toil so hard?"

"Because I am dull," answered the other. "There is no war and the Tzardom is at peace; so, having nothing to do, I amuse myself. But as for strength, I have little enough compared with a certain youth named Ivashko Medvedko."

"I am he," said Little Bear's-Son.

"Then take me with you," said the giant, "and I will be thy younger brother." And he left his road-making and journeyed on with the others.

They traveled for two days, when they passed through a forest of oak-trees, and in it they perceived a third giant as tall as a barn, at work making all the oaks of the same height. If one was too tall, he drove it further into the earth with a blow of his fist, and if too short, he pulled it up to the proper level.

"Health to thee!" said Little Bear's-Son. "Thou art indeed a mighty man. What is thy name?"

"Health to thee!" responded the giant. "My name is Dubynia.[3] But my strength is as naught compared with that of a certain Ivashko Medvedko that I have heard tell of."

"I am that one," said Little Bear's-Son. "Wilt thou go with us and be our comrade?"

"That I will," answered the giant. "Whither doth your path lead?"

"Whither our eyes look," said Little Bear's-Son, and the third giant left his work in the oak-forest and went with them.

They traveled, all four together, for three days, when they came to a wilderness full of all kinds of game, and Little Bear's-Son said: "Of what profit is it for us to wander further through the white world? Let us build a house here and dwell in ease and comfort."

The three giants agreed. All immediately set to work clearing the stubble and preparing the timbers and before nightfall the dwelling was completed. It was built of the hugest trees and was big enough to shelter comfortably forty ordinary men. When it was finished they made a hunt and killed and snared beasts and fowl to fill their larder.

The next morning Little Bear's-Son said: "Each day three of us must hunt so that we lack not food, while the fourth stays at home to guard our house and to cook for the rest. Let us cast lots, therefore, to see who shall stay at home to-day." They cast lots and it fell to Usynia, he of the huge mustache, to remain, and the other three went away to hunt.

When they had departed Usynia took flesh and fowl and prepared a fit meal for his comrades when they should return, and boiled and baked and roasted whatever pleased his soul. When all was ready he washed his head, and sitting down under the window, began to comb his curly locks with a comb.

Suddenly it thundered, the wind began to moan, the earth began to shake and the wild, thick, silent forest bent down to the ground. Usynia grew faint and giddy and everything seemed to turn green. As he looked out of the window, he saw the earth begin to rise, and from under it lifted a huge stone, and from beneath the stone came a Baba-Yaga, riding in a great iron mortar, driving with the pestle and sweeping away her trail behind her with a kitchen broom.

Usynia was badly frightened but he opened the door, and when the old witch came in, wished her good health and gave her a bench to sit on.

"Canst thou not see, thou great lump," snarled the Baba-Yaga, "that I am hungry? Give me to eat!"

Usynia took a roast duck from the oven and some bread and salt, and set them before her. She ate all greedily and demanded more. He brought another piece of meat, but it was so small that she flew into a rage. "Is this how thou servest me?" she cried, and seizing him with her bony arms, she dragged him from side to side of the room, bumped his head on the floor, beat him almost to death with her iron pestle and threw him under the table. Then she cut a strip of skin from his back, snatched everything out of the oven and ate it, bones and all, and drove away in her mortar.

When the bruised giant came to his senses, he tied his handkerchief about his head and sat groaning till his comrades returned.

Seeing, they asked: "Art thou in pain, that thou hast bound up thy head? And where is our supper?"

"Ah, little brothers," he replied, "I have been able neither to boil nor to roast for you. The oven is new and the smoke poured out into the room till it gave me a headache." So Little Bear's-Son and his two comrades prepared their meals themselves.

The next day Gorynia remained at home. He roasted and fried to his heart's content, and when all was done, he washed his head and began to comb his hair, when all at once it lightened, hail began to fall and the trees of the dense, sleepy forest bent over to the ground. He grew faint and giddy and everything seemed to turn green. Then he saw the earth stir, the stone lift, and from beneath it the Baba-Yaga came riding in her mortar, driving with the pestle and sweeping away her trail with her kitchen broom.

Gorynia was too frightened to hide himself, and the old witch came in without knocking. "Health to thee, grandmother!" said the giant, and bade her sit down.

"Dost thou not see that I am hungry and thirsty?" she snapped. "Fetch me food!"

He set a piece of venison and a cup of kwas before her.

She ate and drank and asked for more, and he brought her another piece of meat. This, however, being smaller than the first, did not please her fancy. "Is it thus thou servest me?" she shrieked, and gripping him by the hair with her skinny hands, she dragged him from corner to corner, beat his head against the walls and belabored him with her iron pestle till his senses left him. Then she cut a strip of flesh from his back, threw him under the bench, ate all that he had cooked and drove away.

When the others returned from their hunting, they found Gorynia sitting with his head bandaged and groaning louder than had Usynia the day before. "Alas, little brothers!" he said, when they questioned him, "the wood was damp and would not burn, and from trying to bake and roast for you, my head aches as if it would burst!" So the three cooked their own supper and went to bed.

The next day Dubynia was left at home, while the others hunted, and to him the same thing happened also. The Baba-Yaga appeared, beat him black and blue with her pestle, cut a strip of flesh

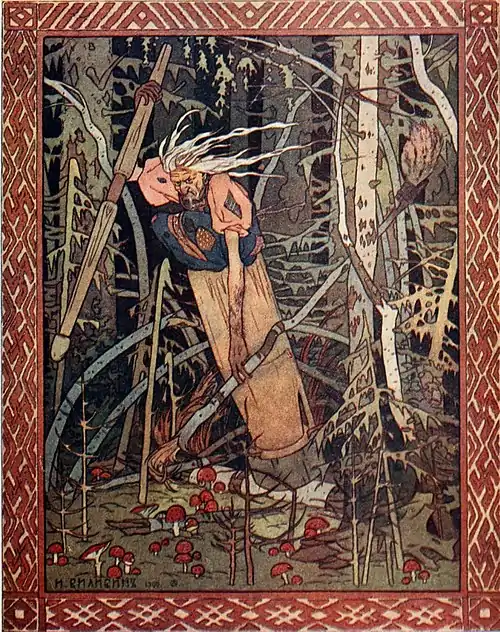

THE BABA-YAGA CAME RIDING IN HER MORTAR, DRIVING WITH THE PESTLE AND SWEEPING AWAY HER TRAIL WITH THE KITCHEN BROOM.

On the fourth day it came the turn of Little Bear's-Son to stay. He put the house to rights, boiled, baked and roasted, and when all was prepared, washed his head, sat down under the window and began to comb his hair. Suddenly rain began to fall, the forest complained and bowed down and everything turned green before his eyes; then the earth parted, the great stone tilted, and out from the hole came the Baba-Yaga, riding in her mortar, driving with her pestle and sweeping out her path behind her with the kitchen broom.

Little Bcar's-Son was not frightened, however, nor was he made giddy. He fetched his iron club of twenty-five poods, stood it ready in a corner and opened the door. "Health to thee, grandmother!" he said.

She hobbled in and sat down, grinding all her teeth and smiling. "Fool!" she said. "Why dost thou not offer me something to eat and drink? Canst thou not see that I am famished?"

"The food that I have cooked," he replied, "is for my comrades, not for thee!"

The old witch snatched up her pestle and sprang upon him, thinking to treat him as she had the others, but he seized her by her gray locks, grasped his iron club, and began to beat her till even her witch's body suffered tortures and she howled for mercy. He stayed not his hand, however, till she was half dead. Then he threw her into a cupboard and locked the door.

Presently the three giants returned, expecting, each one of them, to find Little Bear's-Son well beaten and their supper gone. But he welcomed them, bade them sit down and brought from the oven foods of all sorts, deliciously cooked and in plenty. The giants ate and drank their fill, each one saying to himself: "Surely the Baba-Yaga did not come to our brother to-day!"

When the supper was ended, Little Bear's-Son heated the bath for his comrades and all went to bathe. Now, because the witch had cut the strips of flesh from their backs, each of the three giants tried to stand always with his face toward Little Bear's-Son, lest he see the scar. So at length he asked: "Brothers, why do ye stand thus facing me, like men who fear to show their shoulders?" They turned themselves about then, and he asked: "Why are the scars upon your backs?"

Then Usynia said: "The day I stayed at home the smoke of the fire blinded my eyes, so that I touched the stove and the hot iron seared me." Gorynia said: "When I remained, the wood was damp, and in filling the stove with dry, a fagot dropped from my shoulder and tore my flesh." And Dubynia said: "When I was left behind, the gas from the oven made me giddy, so that I slipped and fell upon thy iron club."

Then Little Bear's-Son laughed, and opening the cupboard door, dragged from thence the Baba-Yaga. "Here, my brothers," he said, "are the smoke, the dampness, and the gas."

Now the old witch was cunning, and she pretended to be still senseless from her beating. She opened one eye a little, however, and seeing her chance, suddenly leaped into her mortar, whirled through the doorway, and in another moment had disappeared beneath the huge stone.

The three giants, angered to find their secret discovered, were still more furious to see the Baba-Yaga outwit them. They ran to the stone and put forth all their strength to turn it, but were unable. Then Little Bear's-Son went to the stone, lifted it and hurled it a verst away. Beneath it was a great dark hole, like the burrow of an enormous fox.

"Brothers," said Little Bear's-Son, "the witch is in this abyss. She is now our mortal enemy and if we do not kill her, she will drive us, one by one, out of the white world. Which of us shall follow her?"

The three giants, however, had tasted the Baba-Yaga's power and had no relish for attacking her under the ground. Dubynia hid behind Gorynia and Gorynia slunk behind Usynia and Usynia looked up at the blue sky as if he had not heard. "Well," said Little Bear's-Son, "it seems that I must be the one to go." He bade them, then, cut into strips the hides of the beasts they had trapped and killed, and to twist the strips into a long rope. He planted a great post in the ground, tied one end of the rope to this and threw the other end into the dark hole. "Now, little brothers," he said, "remain here and watch, one of you at a time. If ye see the rope quiver and shake, lay hold of it straightway and hoist me out."

Little Bear's-Son put food in his pouch, bade the giants farewell and grasping the hide-rope, lowered himself into the yawning abyss. Whether it was a long way or a short way, the rope held and was sufficient and at length he reached the bottom. There he found a trodden path which led him through a long underground passage, till finally he emerged into another world—the world that lies under the earth. He found there a sun and moon, tall trees and wide rivers and green meadows like those of the upper world, but there were no human beings to be seen, nothing but great birds flying in flocks.

He wandered a day, and two, and three, and on the fourth day he came, in a forest, to a wretched little hut standing on fowls' legs and turning round and round without ceasing. About it was a garden and in the garden was a beautiful damsel plucking flowers.

He greeted her and she said: "Health to thee, good youth, but what dost thou here? This is the house of a Baba-Yaga, who if thou remainest will surely devour thee!"

"It is she I seek," he answered.

"Thou art a brave man," the damsel said. "But the witch is a hundred times more powerful here, where she is surrounded by her enchantments, than in the upper-world. She is now asleep but presently she will wake and ride away. Hide thou in the forest till she is gone and I will show thee a way by which, perchance, thou mayest overcome her. Only promise truly that if thou dost succeed, thou wilt take me back with thee to the white world whence she carried me away."

Little Bear's-Son gave the maiden this promise, and concealed himself in the forest, and after a while he felt the ground rumble and saw the trees shiver and bow down, and out of the hut came the Baba-Yaga, riding away in her great iron mortar, driving with the pestle and sweeping out her trail behind her with her kitchen broom. When she was out of sight, he hastened to the hut and the damsel, taking him into the cellar, showed him two great casks full of water, one on the right side and the other on the left.

"Drink," she bade him, "from the right cask, as much as thou canst hold."

He stooped down and took a long drink, when she asked: "How strong art thou now?"

"I am so strong," he answered, "that with one finger I could lift and carry away this cask."

"Drink again," she commanded.

Again he drank. "Now," she asked, "how much strength is in thee?"

"I am so strong," he replied, "that if I chose, with one hand I could lift and turn about this whole hut!"

"Listen well," she said, "to what I tell thee. The cask from which thou hast drunk contains Strong Water. It is this which gives the Baba-Yaga her strength. The cask on the left holds Weak Water, and whoever drinks from it is made quickly powerless. As soon as the witch appears, seize tightly her pestle before she lays it down, and loose not thy grip as thou lovest thy life. She will try to shake thee off, but thou art now so strong that she will not be able to do so. Failing in this, she will hasten here to drink of the Strong Water. Change, therefore, now, the two casks and put each in the place of the other, so that she will be deceived and will drink of the Weak Water, and then thou mayst kill her. When thou drawest thy sword, however, strike but a single stroke. Her mortar, her pestle, and her broom, all her faithful servants, will cry out to thee to strike again, but if thou strikest a second stroke, she will instantly come to life again. Beware also to draw thy sword before she has drunk of the Weak Water, for until then it will be powerless against her spells."

Little Bear's-Son immediately changed the places of the two casks, putting the right one on the left hand and the Weak Water where the Strong Water had been. And soon, as he conversed with the lovely maiden in the garden, the trees began to sob and the timbers of the hut to creak, and the Baba-Yaga came riding home. Little Bear's-Son hid himself behind a hedge and the old witch stopped and leaped down from her mortar.

"Poo! poo!" she cried, smelling around her. "I smell a Russian smell! Who has visited here?"

"No one, grandmother," said the damsel. "How could one from the upper-world find his way here?"

"Well," said the Baba-Yaga, "I fear no one here save a Russian named Ivashko Medvedko, and he is so far away at this moment that it would take a he-crow a year to fly hither with one of his bones."

"Thou liest, old witch!" cried Little Bear's-Son, and with the words sprang out and seized hold of her iron pestle. The Baba-Yaga whistled and spat and howled with rage, but try as she might, she could not shake him off. She tore away in a whirlwind, over the tree-tops of the forest, striving to dash him down to pieces. She whirled him high over a broad river, trying to fling him down to drown, threatening him with all dreadful tortures. But Little Bear's-Son held on with all the strength he had gained from drinking the Strong Water, and she could not break his hold. She dragged him back and forth over the whole under-world in vain, till at length even she grew tired. Then back she flew to the hut and dropping her pestle, pounced down into the cellar and began to drink from the cask on the right hand.

Hardly, however, had the Baba-Yaga rushed from the cellar to attack Little Bear's-Son again, than she became all at once as weak as a blade of grass, and drawing his sword, with a single blow, he cut off her wicked old head.

Instantly the iron mortar and pestle and the kitchen broom cried out to him: "Strike again! Strike again!" But, remembering what the damsel had said, he answered: "A brave man's sword strikes not twice," and sheathed it.

Little Bear's-Son made a great fire in the forest and burned the witch's body to ashes. Then, taking the lovely maiden with him, he set out on his return to the upper-world.

For two days they journeyed, and on the second day rain began to fall, so that they took refuge under a tree. Near by Little Bear's-Son saw a great bird's-nest with fledglings in it, and pitying the young ones, which were being drenched, he hung his cloak above the nest to protect them. Presently the rain ceased and they went on till they reached the underground passage and followed it to the place where the hide-rope hung. Little Bear's-Son tied the damsel to its end and shook it, and one of the three giants, who was watching above, ran to fetch the other two and they began to pull up the rope.

When they saw the beauty of the maiden, however, the three giants were envious of their comrade and each wished her for his wife. So they agreed together and when they had hoisted Little Bear's-Son, in his turn, almost to the top, they cut the rope and let him fall and straightway began to quarrel over which of them should marry her.

Little Bear's-Son was terribly hurt by his fall, but so strong had he become that he was not killed. He lay on his back one day, he lay on his side two days and three, and then he managed to walk through the long passage into the under-world again. While he wandered there, wondering what he should do, there came flying one of the huge birds whose flocks he had seen, and alighting near him, it spoke to him with a human voice.

"Thou didst have pity on my fledglings, Ivashko Medvedko," it said, "and in return for this I will serve thee a service. Ask of me what thou wilt."

"If thou art able," replied Little Bear's-Son, "take me out into the white world."

"It is a hard service," said the bird, "but there is a way I know and I will carry thee. The journey, however, will take three months. Go now into the forest and snare much game and twist a wicker basket and fill it. Mount my back with this and whenever I turn my head as I fly, feed me."

Little Bear's-Son did as he was bidden. He made a great basket, filled it with game and mounted with it to the back of the huge bird, which at once rose into the air and flew away like a hurricane. It flew day after day, without stopping. As often as it turned its head, he fed it with some of the game from the basket, and when it had flown for three months and the basket was almost empty, it carried him out into the white world, set him down in a grassy meadow, bade him farewell and flew away.

Whether it was a long way or a short way, Little Bear's-Son came at length to his own Tzardom and to the forest wherein stood the house that he and the three giants had built. A little way within the forest he saw a green lawn and on it a lovely girl was tending cows. He drew near and found to his surprise that she was none other than the damsel he had rescued from the hut of the Baba-Yaga.

She greeted him with joy and told him all that had befallen her: how the giants had quarreled over her, how they had fought each day for an hour, but as no one of them was stronger than another, had not been able to decide and had made her tend their cattle till one should prevail. Then he kissed her on the mouth and said he: "Thou shalt wed no one of those faithless brothers of mine, but I will wed thee myself."

Little Bear's-Son sent her on before him, and coming to the hut where the three giants sat at the window drinking, pulled his cap over his face and in a humble tone asked for a drink of kwas.

"Be off with thee!" grunted Usynia, without turning his head.

"We want no beggars here!" snarled Gorynia.

"Kwas, forsooth!" shouted Dubynia. "Thou shalt have a taste of my club instead!"

Then Little Bear's-Son took off his cap and they recognized him. They turned pale with fright and making for the door, ran away as if the Tartars were after them, and were never seen in that Tzardom again. And Little Bear's-Son married the lovely damsel and they dwelt in that house all their lives in such peace and comfort that they wanted nothing they did not have and had nothing they did not want.