POPULAR MISCELLANY.

713

so good in all respects as Portland cement. Another kind of slag—the Thomas, or "basic slag," produced in making steel—is remarkable for its richness in phosphoric acid, and is coming into use as a fertilizing material. The demand for it in Germany already exceeds the whole available production of the country, and it is imported from Great Britain and Austria.

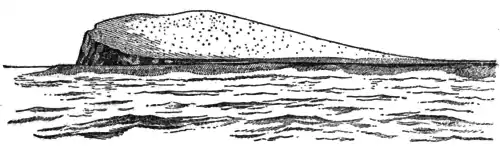

The Formation of a New Island.—An interesting account of the newly emerged volcanic island of the Tonga group is given by Mr. J. J. Lister in the Proceedings of the Royal Geographical Society for March. It has received the name of Falcon Island, and was formed by an eruption in 1885. It was visited during its formation by some natives of the group, who say that the center of action was wholly on one side of the present island; showing that in all probability the wind played an important part in determining its position. The uncovered portion lies approximately northwest of the supposed center. It consists of two parts: a conical mound at its southern end, about one hundred and fifty-three feet high, and a flat extending to the northward, which is from ten to twelve feet above high water. There is a considerable shoal area north of the flat, but at the base of the higher portion the water deepens rapidly. The soil of the island consists of a fine-grained, dark-gray material arranged in strata. The strata are marked by difference in color and the varying thickness of the salts which have crystallized on them. The soil below the surface was found still hot; the temperature at a depth of seven feet being 100° Fahr., while at the surface it was only 74°. With the exception of two young cocoanut-trees, which seemed not very hardy, there was no vegetation but a few bunches of grass; and a moth and small sand-piper constituted the animal population. The island will probably have disappeared in a few years, unless another eruption occurs, as the waves are rapidly wearing the shore line away.

Falcon Island.

The Unselfishness of Doctors.—Dr. Robert G. Eccles, in a lecture on the Evolution of Medical Science, delivered before the Brooklyn Ethical Association, pays a just tribute to the unselfishness of the medical profession. Medicine, he says, "in all ages has attracted into its ranks the most self-sacrificing members of society. As a science, it was born in altruism. To this day it offers the greatest opportunities of any department of life for the practice of the most ennobling graces of character. These constitute a primary cause of its evolution. . . . Medical men stand alone in the earth among all others, striving with their whole might to extinguish their own business. They preach temperance, virtue, and cleanliness, knowing well that, when the people come to follow their advice, their occupation, like Othello's, will be gone. They establish Boards of Health, to arrest the spread of disease, while well aware that such sanitary measures steal money from their purses. How well they succeed is shown by official statistics. . . . Nobody ever fails to send for a physician in typhus fever. Only six persons in a million die of this disease. Many more used to die when no effort toward its suppression was made. Whooping-cough seldom frightens patients, and neighborly old ladies of both sexes give advice. As a consequence, 428 in a million die of this disease. Measles, being a little more serious, needs the doctor oftener, and only 341 in a million die. Scarlet fever is still more alarming, so that medical advice is more in demand, and 222 in a million die of it. Diphtheria frightens