SHOWING OFF; OR, THE LOOKING-GLASS BOY

His parents had thoughtlessly christened him Hildebrand, a name which, as you see, is entirely unsuitable for school use. His friends called him Brandy, and that was bad enough, though it had a sort of pirate-smuggler sound, too. But the boys who did not like him called him Hilda, and this was indeed hard to bear. In vain he told them that his name was James as well. It was not true, and they would not have believed it if it had been.

He had not many friends, because he was not a very nice boy. He was not very brave, except when he was in a rage, which is a poor sort of courage, anyhow; and when the boys used to call him 'Cowardy custard' and other unpleasing names, he used to try to show off to them, and make them admire him by telling them stories of the wild boars he had killed, and the Red Indians he had fought, and of how he had been down Niagara in an open boat, and been shipwrecked on the high seas. They were not bad stories, and the boys would not have minded listening to them, but Hildebrand wanted to have his stories not only listened to, but believed, which is quite another pair of shoes.

He had one friend who always liked his stories, and believed them almost all. This was his little sister. But he was simply horrid to her. He never would lend her any of his toys, and he called her 'Kiddie,' which she hated, instead of Ethel, which happened to be her name.

All this is rather dull, and exactly like many boys of your acquaintance, no doubt. But what happened to Hildebrand does not, fortunately or unfortunately, happen to everybody; I dare say it has never happened to you. It began on the day when Hildebrand was making a catapult, and Billson Minor came up to him in the playground and said:

'Much use it'll be to you when you've made it. You can't hit a haystack a yard off!'

'Can't I?' said Hildebrand. 'You just see! I hit a swallow on the wing last summer, and when we had a house in Thibet I shot a llama dead with one bullet. He was twenty-five feet long.'

Billson laughed, and asked a boy who was passing if he'd ever been out llama-shooting, and, if so, what his bag was. The other boy said:

'Oh, I see—little Hilda gassing again!'

Billson said:

'Gassing! Lying I call it!'

'Liar yourself!' said Hildebrand, who was now so angry that his fingers trembled too much for him to e able to go on splicing the catapult.

'Oh, run away and play,' said Billson wearily. 'Go home to nurse, Hilda darling, and tell her to put your hair in curl-papers!'

Then Hildebrand's rage turned into a sort of courage, and he hit out at Billson, who, of course, hit back, and there was a fight. The other boy held their coats and saw fair; and Hildebrand was badly beaten, because Billson was older and bigger and a better fighter, so he went home, crying with fury and pain. He went up into his own bedroom and bolted the door, and wildly wished that he was a Red Indian, and that taking scalps was not forbidden in Clapham. Billson's, he reflected gloomily, would have been a sandy-coloured scalp, and a nice beginning to a scalp-album.

Presently he stopped crying, and let his little sister in. She had been crying, too, outside the door, ever since he came home and pushed past her on the stairs. She pitied his bruised face, and said it was a shame of Billson Minor to hit a boy littler than he was.

'I'm not so very little,' said Hildebrand; 'and you know how brave I am. Why, it was only last week that I was the chief of the mighty tribe of Moccasins, who waged war against Bill Billson, the Vulture-faced Redskin'

He told the story to its gory end, and Ethel liked it very much, and hoped it wasn't wrong to make up such things. She couldn't quite believe it all.

Then she went down, and Hildebrand had to wash his face for dinner; and when he looked at the boy in the looking-glass and saw the black eye Billson Minor had given him, and the cut lip from the same giver, he clenched his fist and said:

'I wish I could make things true by saying them. Wouldn't I bung up old Billson's peepers, that's all?'

'Well, you can if you like,' said the boy in the glass, whom Hildebrand had thought was his own reflection.

'What?' said he, with his mouth open. He was horribly startled.

'You can if you like,' said the looking-glass boy again. 'I'll give you your wish. Will you have it?'

'Is this a fairy-tale?' asked Hildebrand cautiously.

'Yes,' said the boy.

Hildebrand had never expected to be allowed to take part in a fairy-tale, and at first he could hardly believe in such luck.

'Do you mean to say,' he said, 'that if I say I found a pot of gold in the garden yesterday I did find a pot of gold?'

'No; you'll find it to-morrow. The thing works backwards, you see, like all looking-glass things. You know your "Alice," I suppose? There's only one condition: you won't be able to see yourself in the looking-glass any more!'

'Who wants to,' said Hildebrand.

'And things you say to yourself don't count.'

'There's always Ethel,' said Ethel's brother.

'You accept, then?' said the boy in the glass.

'Rather!'

'Right.' And with that the looking-glass boy vanished, and Hildebrand was left staring at the mirror, which now reflected only the wash-hand-stand and the chest of drawers, and part of the picture of Lord Roberts pinned against the wall. You have no idea how odd and unpleasant it is to look at a glass and see everything reflected as usual, except yourself, though you are right in front of it. Hildebrand felt as if he must have vanished as well as the looking-glass boy. But he was reassured when he looked down at his hands. They were still there, and still extremely dirty. The second bell had rung, and he washed them hastily and went down.

'How untidy your hair is!' said his mother; 'and oh, Hildebrand, what a disagreeable expression, dear! and look at your eye! You've been fighting again.'

'I couldn't help it,' said our hero sulkily; 'he called names. Anyway, I gave him an awful licking. He's worse than I am. Potatoes, please.'

Next day Hildebrand had forgotten the words he had said at dinner. And when Billson asked him if one licking was enough, and whether he, Billson, was a liar or not, Hildebrand said: 'You can lick me and make me anything you like, but you are all the same, just as much as me,' and he began to cry.

And Billson called him schoolgirl and slapped his face—because Billson knew nothing of the promise of the looking-glass boy, that whatever Hildebrand said had happened should happen.

It was a dreadful fight, and when it was over Hildebrand could hardly walk home. He was much more hurt than he had been the day before. But Billson Minor had to be carried home. Only he was all right again next day, and Hildebrand wasn't, so he did not get much out of this affair, except glory, and the comfort of knowing that Billson and the other boys would now be jolly careful how they called him anything but Pilkings, which was his father's and his mother's name, and therefore his as well.

He had to stay in bed the next day, and his father punished him for fighting, so he consoled himself by telling Ethel how he had found a pot of gold in the cellar the day before, after digging in the hard earth for hours, till his hands were all bleeding, and how he had hidden it under his bed.

'Do let me see, Hildy dear,' she said, trying hard to believe him.

But he said, 'No, not till to-morrow.'

Next day he was well enough to go to school, but he thought he would just take some candle-ends and have a look at the cellar, and see if it was really likely that there was any gold there. It did not seem probable, but he thought he would try, and he did. It was terribly hard work, for he had no tools but a spade he had had at the seaside, and when that broke, as it did almost at once, he had to go on with a piece of hoop-iron and the foot of an old bedstead. He went on till long past dinner-time, and his hands were torn and bleeding, his back felt broken in two, and his head was spinning with hunger and tiredness. At last, just as the tea-bell rang, he reached his hand down deep into the hole he had made, and felt something cold and round. He held his candle down. It was a pot, tied over with brown paper, like pickled onions. When he got it out he took off the paper. The pot was filled to the brim with gold coins. Hildebrand blew out his candle and went up. The cook stopped him at the top of the cellar stairs.

'What's that you got there, Master Hildy? Pickles, I lay my boots,' she said.

'It's not,' said he.

'Let me look,' said she.

'Let me alone,' said Hildebrand.

'Not me,' said the cook.

She had her hand on the brown paper.

Hildebrand had heard how treasure-trove has to be given up to Government, and he did not trust the cook.

'You'd better not,' he said quickly; 'it's not what you think it is.'

'What is it, then?'

'It's—it's snakes!,' said Hildebrand desperately—'snakes out of the wine-cellar.'

The cook went into hysterics, and Hildebrand was punished twice, once for staying away from school without leave, and once for frightening the servants with silly stories. But in the confusion brought about by the cook's screams he managed to hide the pot of gold in the bottom of the boot cupboard, among the old gaiters and goloshes, and when peace was restored and he was sent to bed in disgrace he took the pot with him. He lay long awake thinking of the model engine he would buy for himself, also of the bay pony, the collections of coins, birds' eggs, and postage-stamps, the fishing-rods, the guns, revolvers, and bows and arrows, the sweets and cakes and nuts, he would get all for himself. He never thought of so much as a pennyworth of toffee for Ethel, or a silver thimble for his mother, or a twopenny cigar for Mr. Pilkings.

The first thing in the morning he jumped up and felt under the bed for the pot of gold. His hand touched something that was not the pot. He screamed, and drew his hand back as quickly as though he had burned it; but what he had touched was not hot: it was cold, and thin, and alive. It was a snake. And there was another on his bed, and another on the dressing-table, and half a dozen more were gliding about inquisitively on the floor.

Hildebrand gathered his clothes together—a snake tumbled out of his shirt as he lifted it and made one bound for the door. He dressed on the landing, and went to school without breakfast. I am glad to be able to tell you that he did say to Sarah the housemaid:

'For goodness' sake don't go into my bedroom—it's running alive with snakes!'

She did not believe him, of course; and, indeed, when she went up the snakes were safe back in the pot. She did not see this, because she was not the kind of girl who sweeps under things every day. That night Hildebrand secretly slept in the box-room, on a pile of newspapers, with a rag-bag and a hearthrug over him.

Next day he said to Sarah:

'Did you go into my room yesterday?'

'Of course,' said she.

'Did you take the snakes away?'

'Go along with your snakes!' she said.

So he understood that she had not seen any, and very cautiously he looked into his room, and finding it snakeless, crept in, hoping that the snakes had changed back into gold. But they had not snakes and gold and pot had all vanished. Then he thought he would be very careful. He said to Ethel:

'I had twenty golden sovereigns in my pocket yesterday.'

This was Saturday. Next day was Sunday, and all day long he jingled the twenty golden sovereigns he had found that morning in his knickerbocker pocket. But they were not there on Monday. And then he saw that though he could make things happen, he could not make them last. So he told Ethel he had had seven jam-tarts. He meant to eat them as soon as he got them. But the next day when they came he had a headache and did not want to eat them. He might have given them to Ethel, but he didn't, and next day they had disappeared.

It was very annoying to Hildebrand to know that he had this wonderful power, yet he could not get any good out of it. He tried to consult his father about it, but Mr. Pilkings said he had no time for romances, and he advised Hildebrand to learn his lessons and stick to the truth. But this was just what Hildebrand could not do, even after the awful occasion when his schoolfellows began to tease him again, and, to command their respect, he related how he had met a bear in the lane by the church and fought it single-handed, and been carried off more dead than alive. Next day, of course, he had to fight the bear, which was very brown and clawy and toothy and fierce, and though the more-dead-than-alive feeling had gone by next day, it was not a pleasant experience. But even that was better than the time when they laughed at a very bad construe of his—the form was in Cæsar—and he told them how he had once translated the inscription on an Egyptian Pyramid. He had no peace for weeks after that, because he had forgotten to say how long it took him. Every time he was alone he was wafted away to Egypt and set down at that Pyramid. But he could not find the inscription, and if he had found it he could not have translated it. So, in self-defence, he spent most of his waking-time with Ethel. But every night the Pyramid had its own way, and it was not till he had cut an inscription himself on the Pyramid with the broken blade of his pocket-knife, and translated it into English, that he was allowed any rest at all. The inscription was Ich bin ein Ganz, and you can translate it for yourself.

But that did him good in one way; it made him fonder of Ethel. Being so much with her, he began to see what a jolly little girl she really was. When she had measles—Hildebrand had had them, or it, last Christmas, so he was allowed to see his sister—he was very sorry, and really wished to do something for her. Mr. Pilkings brought her some hothouse grapes one day, and she liked them so much that they were very soon gone. Then Hildebrand, who had been very careful since the Pyramid occasion to say nothing but the truth, said:

'Ethel, some grapes and pineapples came for you yesterday.'

Ethel knew it wasn't true, but she liked the idea, and said:

'Anything else ?'

'Oh yes!' said her brother—'a wax doll and a china tea-set with pink roses on it, and books and games,' and he went on to name everything he thought she would like.

And, of course, next day the things came in a great packing-case. No one ever knew who sent them, but Mr. and Mrs. Pilkings thought it was Ethel's godfather in India. And, curiously enough, these things did not vanish away, but were eaten and enjoyed and played with as long as they lasted. Ethel has one of the dolls still, though now she is quite grown up.

Now Hildebrand began to feel sorry to see how ill and worried his mother looked; she was tired out with nursing Ethel, so he said to Sarah:

'Mother was quite well yesterday.'

Sarah answered:

'Much you know about it; your poor ma's wore to a shadow.'

But next day mother was quite well, and this lasted, too. Then he wanted to do something for his father, and as he had heard Mr. Pilkings complain of his business being very bad, Hildebrand said to Ethel:

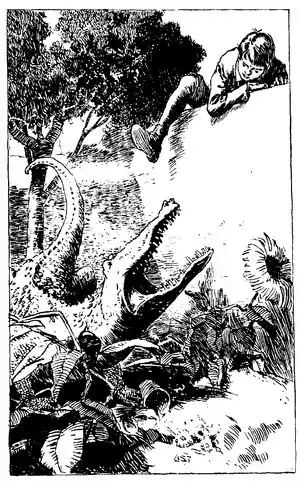

'The alligator very nearly had him.'—Page 195.

And next day Mr. Pilkings came home and kissed Mrs. Pilkings in the hall under the very eyes of Sarah and the boot-boy, and said:

'My dear, our fortune's made!'

The family did not have any nicer things to eat or wear than before, so Hildebrand gained nothing by this, unless you count the pleasure he had in seeing his father always jolly and cheerful and his mother well, and not worried any more. Hildebrand did count this, and it counted for a good deal.

But though Hildebrand was now a much happier as well as a more agreeable boy, he could not quite help telling a startling story now and then. As, for instance, when he informed the butcher's boy that there was an alligator in the back-garden. The butcher's boy did not go into the garden—indeed, he had no business there, though that would have been no reason if he had wanted to go—but next day, when Hildebrand, having forgotten all about the matter, went out in the dusk to look for a fives ball he had lost, the alligator very nearly had him.

And when he related that adventure of the lost balloon, he had to go through with it next day, and it made him dizzy for months only to think of it.

But the worst thing of all was when Ethel was well, and he was allowed to go back to school. Somehow the fellows were much jollier with him than they used to be. Even Billson Minor was quite polite, and asked him how the kid was.

'She's all right,' said Hildebrand.

'When my kiddie sister had measles,' Billson said, 'her eyes got bad afterwards; she could hardly see.'

'Oh,' said Hildebrand promptly, 'my sister's been much worse than that; she couldn't see at all.'

When Hildebrand went home next day he found his mother pale and in tears. The doctor had just been to see Ethel's eyes—and Ethel was blind.

Then Hildebrand went up to his own room. He had done this—his own little sister who was so fond of him. And she was such a jolly little thing, and he had made her blind, just for a silly bit of show-off to Billson Minor; and he knew that the things he had said about Ethel before had come true, and had not vanished like the things he said about himself, and he felt that this, too, would last, and Ethel would go on being blind always. So he lay face down on his bed and cried, and was sorry, and wished with all his heart that he had been a good boy, and had never looked in the glass, and wished to bung up the eyes of Billson Minor, who, after all, was not such a bad sort of chap.

When he had cried till he could not cry any more he got up, and went to the looking-glass to see if his eyes were red, which is always interesting. He never could remember that he couldn't see himself in the glass now. Then suddenly he knew what to do. He ran down into the street, and said to the first person he met:

'I say, I saw the looking-glass boy yesterday, and he let me off things coming true, and Ethel was all right again.'

It was a policeman, and the constable boxed his ears, and promised to run him in next time he had any of his cheek. But Hildebrand went home calmer, and he read 'The Jungle Book' aloud to Ethel all the evening.

Next morning he ran to his looking-glass, and it was strange and wonderful to him to see his own reflection again after all these weeks of a blank mirror, and of parting his hair as well as he could just by feeling. But it wasn't his own reflection, of course: it was the looking-glass boy.

'I say, you look very different to what you did that day,' said Hildebrand slowly.

'So do you,' said the boy.

That other day, which was weeks ago, the looking-glass boy had been swollen and scowling and angry, with a black eye and a cut lip, and revengeful looks and spiteful words. Now he looked pale and a little thinner, but his eyes were only anxious, and his mouth was kind. It was just the same ugly shape as ever, but it looked different. And Hildebrand was as like the boy in the glass as one pin is like another pin.

'I say,' said Hildebrand suddenly and earnestly, 'let me off; I don't want it any more, thank you. And oh, do—do make my sister all right again.'

'Very well,' said the boy in the looking-glass; 'I'll let you off for six months. If you haven't learned to speak the truth by then—well, you'll see. Good-bye.'

He held out his hand, and Hildebrand eagerly reached out to shake it. He had forgotten the looking-glass, and it smashed against his fist, and cracked all over. He never saw the boy again, and he did not want to.

When he went down Ethel's eyes were all right again, and the doctor thought it was his doing, and was as proud as a King and as pleased as Punch. Hildebrand could only express his own gladness by giving Ethel every toy he had that he thought she would like, and he was so kind to her that she cried with pleasure.

Before the six months were up Hildebrand was as truthful a boy as anyone need wish to meet. He made little slips now and then, just at first, about his escape from the mad bull, for instance, and about the press-gang.

His stories did not come true next day any more, but he had to dream them, which was nearly as bad. So he cured himself, and did his lessons, and tried to stick to the truth; and when he told romances he let people know what he was playing at. Now he is grown up he dreams his stories first, and writes them afterwards; for he writes books, and also he writes for the newspapers. When you do these things you may tell as many stories as you like, and you need not be at all afraid that any of them will come true.

This work is in the public domain in the United States because it was published before January 1, 1927.

The author died in 1924, so this work is also in the public domain in countries and areas where the copyright term is the author's life plus 95 years or less. This work may also be in the public domain in countries and areas with longer native copyright terms that apply the rule of the shorter term to foreign works.