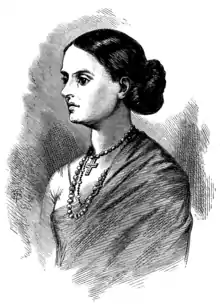

ANNA LIBERATA DE SOUZA (Ayah),

THE NARRATOR.

THE NARRATOR'S NARRATIVE.

MY grandfather's family were of the Lingaet caste, and lived in Calicut; but they went and settled near Goa at the time the English were there. It was there my grandfather became a Christian. He and his wife, and all the family, became Christians at once, and when his father heard it he was very angry, and turned them all out of the house. There were very few Christians in those days. Now you see Christians everywhere, but then we were very proud to see one anywhere. My grandfather was Havildar[1] in the English army; and when the English fought against Tippo Sahib my grandmother followed him all through the war. She was a very tall, fine, handsome woman, and very strong; wherever the regiment marched she went, on, on, on, on, on ('great deal hard work that old woman done'). Plenty stories my granny used to tell about Tippo and how Tippo was killed, and about Wellesley Sahib, and Monro Sahib, and Malcolm Sahib, and Elphinstone Sahib.[2] Plenty things had that old woman heard and seen. Ah, he was a good man, Elphinstone Sahib! My granny used often to tell us how he would go down and say to the soldiers, 'Baba,[3] Baba, fight well. Win the battles, and each man shall have his cap full of money; and after the war is over I'll send every one of you to his own home.' (And he did do it.) Then we children 'plenty proud' when we heard what Elphinstone Sahib had said. In those days the soldiers were not low-caste people like they are now. Many very high caste men, and come from very far, from Goa, and Calicut, and Malabar, to join the English.

My father was a tent lascar,[4] and when the war was over my grandfather had won five medals for all the good he had done, and my father had three; and my father was given charge of the Kirkee stores.[5] My grandmother and mother, and all the family, were in those woods behind Poona at time of the battle at Kirkee.[6]I've often heard my father say how full the river was after the battle—baggage and bundles floating down, and men trying to swim across—and horses and all such a bustle. Many people got good things on that day. My father got a large chattee, and two good ponies that were in the river, and he took them home to camp; but when he got there the guard took them away. So all his trouble did him no good.

We were poor people, but living was cheap, and we had 'plenty comfort.'

In those days house rent did not cost more than half a rupee[7]a month, and you could build a very comfortable house for a hundred rupees. Not such good houses as people now live in, but well enough for people like us. Then a whole family could live as comfortably on six or seven rupees a month as they can now on thirty. Grain, now a rupee a pound, was then two annas a pound. Common sugar, then one anna a pound, is now worth four annas a pound. Oil which then sold for six pice a bottle now costs four annas. Four annas' worth of salt, chillies, tamarinds, onions, and garlic, would then last a family a whole month, now the same money would not buy a week's supply. Such dungeree[8] as you now pay half rupee a yard for, you could then buy from twenty to forty yards of for the rupee. You could not get such good calico then as now, but the dungeree did very well. Beef then was a pice a pound, and the vegetables cost a pie a day. For half a rupee you could fill the house with wood. Water also was much cheaper. You could then get a man to bring you two large skins full, morning and evening, for a pie, now he would not do it under half a rupee or more. If the children came crying for fruit, a pie would get them as many guavas as they liked in the bazaar. Now you'd have to pay that for each guava. This shows how much more money people need now than they did then.[9]

The English fixed the rupee to the value of sixteen annas; in those days there were some big annas and some little ones, and you could sometimes get twenty-two annas for a rupee.

I had seven brothers and one sister. Things were very different in those days to what they are now. There were no schools then to send the children to, it was only the great people who could read and write. If a man was known to be able to write he was 'plenty proud,' and hundreds and hundreds of people would come to him to write their letters. Now you find a pen and ink in every house! I don't know what good all this reading and writing does. My grandfather couldn't write, and my father couldn't write, and they did very well; but all's changed now.

My father used to be out all day at his work, and my mother often went to do coolie-work,[10] and she had to take my father his dinner (my mother did plenty work in the world); and when my granny was strong enough she used sometimes to go into the bazaar, if we wanted money, and grind rice for the shopkeepers, and they gave her half a rupee for her day's work, and used to let her have the bran and chaff besides. But afterwards she got too old to do that, and besides there were so many of us children. So she used to stay at home and look after us while my mother was at work. 'Plenty bother' 'tis to look after a lot of children. No sooner my granny's back turned than we all ran out in the sun, and played with the dust and stones on the road.

Then my granny would call out to us, 'Come here, children, out of the sun, and I'll tell you a story. Come in, you'll all get headaches.' So she used to get us together (there were nine of us, and great little fidgets, like all children) into the house; and there she'd sit on the floor, and tell us one of the stories I tell you. But then she used to make them last much longer, the different people telling their own stories from the beginning as often as possible; so that by the time she'd got to the end she had told the beginning over five or six times. And so she went on, talk, talk, talk, Mera Bap reh![11] Such a long time she'd go on for, till all the children got quite tired and fell asleep. Now there are plenty of schools to which to send the children, but there were no schools when I was a young girl; and the old women, who could do nothing else, used to tell them stories to keep them out of mischief.

We used sometimes to ask my grandmother, 'Are those stories you tell us really true?' Were there ever such people in the world?' She generally answered, 'I don't know, but may be there are somewhere.' I don't believe there are any of those people living; I dare say, however, they did once live; but my granny believed more in those things than we do now. She was a Christian, she worshipped God and believed in our Saviour, but still she would always respect the Hindoo temples. If she saw a red stone, or an image of Gunputti or any of the other Hindoo gods, she would kneel down and say her prayers there, for she used to say, 'May be there's something in it.'

About all things she would tell us pretty stories—about men, and animals, and trees, and flowers, and stars. There was nothing she did not know some tale about. On the bright cold-weather nights, when you can see more stars than at any other time of the year, we used to like to watch the sky, and she would show us the Hen and Chickens,[12] and the Key,[13] and the Scorpion, and the Snake, and the Three Thieves climbing up to rob the Ranee's silver bedstead, with their mother (that twinkling star far away) watching for her sons' return. Pit-a-pat, pit-a-pat, you can see how her heart beats, for she is always frightened, thinking, 'Perhaps they will be caught and hanged!'

Then she would show us the Cross,[14] that reminds us of our Saviour's, and the great pathway of light[15] on which He went up to heaven. It is what you call the Milky Way. My granny usen't to call it that; she used to say that when our Lord returned up to heaven that was the way He went, and that ever since it has shone in memory of His ascension, so beautiful and bright.

She always said a star with a smoky tail (comet) meant war, and she never saw a falling star without saying, 'There's a great man died;' but the fixed stars she used to think were all really good people, burning like bright lamps before God.

As to the moon, my granny used to say she is most useful to debtors who can't pay their debts. Thus—A man who borrows money he knows he cannot pay takes the full moon for witness and surety. Then, if any man so silly as to lend him money, and go and ask him for it, he can say, 'The moon's my surety, go catch hold of the moon!' Now, you see, no man can do that; and what's more, when the moon's once full, it grows every night less and less, and at last goes out altogether.

All the Cobras in my grandmother's stories were seven-headed. This puzzled us children, and we would say to her, 'Granny, are there any seven-headed Cobras now? For all the Cobras we see that the conjurors bring round have only one head each.' To which she used to answer, 'No, of course there are no seven-headed Cobras now. That world is gone, but you see each Cobra has a hood of skin, that is the remains of another head.' Then we would say, 'Although none of those old seven-headed Cobras are alive now, may be there are some of their children living somewhere.' But at this my granny used to get vexed, and say, 'Nonsense, you are silly little chatterboxes, get along with you.' And, though we often looked for the seven-headed Cobras, we never could find any of them.

My old granny lived till she was nearly a hundred: when she got very old she rather lost her memory, and often made mistakes in the stories she told us, telling a bit of one story and then joining on to it a bit of some other; for we children bothered her too much about them, and sometimes she used to get very tired of talking, and when we asked her for a story, would answer, 'You must ask your mother about it, she can tell you.'

Ah! those were happy days, and we had plenty ways to amuse ourselves. I was very fond of pets: when I was seven years old I had a little dog that followed me everywhere, and played all sorts of pretty tricks, and I and my youngest brother used to take the little sparrows out of their nests on the roof of our house, and tame them. These little birds got so fond of me they would always fly after me; as I was sweeping the floor one would perch on my head, and two or three on my shoulders, and the rest came fluttering after. But my poor father and mother used to shake their heads at me when they saw this, and say, 'Ah! naughty girl, to take the little birds out of their nests; that stealing will bring you no good.' All my family were very fond of music. You know that Rosie (my daughter) sings very nicely and plays upon the guitar, and my son-in-law plays on the pianoforte and the fiddle (we've got two fiddles in our house now), but Mera Bap reh! how well my grandfather sang! Sometimes of an evening he would drink a little toddy,[16] and be quite cheerful, and sing away; and all we children liked to hear him. I was very fond of singing. I had a good voice when I was young, and my father used to be so fond of making me sing, and I often sang to him that Calicut song about the ships sailing on the sea[17] and the little wife watching for her husband to come back, and plenty more that I forget now; and my father and brothers would be so pleased at my singing, and laugh and say, 'That girl can do anything.' But now my voice is gone, and I didn't care to sing any more since my son died, and my heart been so sad.

In those days there were much fewer houses in Poona than there are now, and many more wandering gipsies, and such like. They were very troublesome, doing nothing but begging and stealing, but people gave them all they wanted, as it was believed that to incur their ill-will was very dangerous. It was not safe even to speak harshly of them. I remember one day, when I was quite a little girl, running along by my mother's side, when she was on her way to the bazaar, we happened to pass the huts of some of these people; and I said to her, 'See, mother, what nasty, dirty people those are; they live in such ugly little houses, and they look as if they never combed their hair nor washed.' When I said this my mother turned round quite sharply and boxed my ears, saying, 'Because God has given you a comfortable home and good parents, is that any reason for you to laugh at others who are poorer and less happy?'—'I meant no harm,' I said, and when we got home I told my father what my mother had done, and he said to her, 'Why did you slap the child?' She answered, 'If you want to know, ask your daughter why I punished her. You will then be able to judge whether I was right or not.' So I told my father what I had said about the gipsies, and when I told him, instead of pitying me, he also boxed my ears very hard. So that was all I got for telling tales against my mother!

But they both did it, fearing if I spoke evil of the gipsies and were not instantly punished some dreadful evil would befall me.

It was after my granny that I was named 'Anna Liberata.' She died after my father, and when I was eleven years old. Her eyes were quite bright, her hair black, and her teeth good to the last. If I'd been older then, I should have been able to remember more of her stories. Such a number as she used to tell! I'm afraid my sister would not be able to remember any of them. She has had much trouble; that puts those sort of things out of people's heads; besides, she is a goose. She is younger than I am, although you would think her so much older, for her hair turned grey when she was very young, while mine is quite black still. She is almost bald too, now. as she pulled out her hair because it was grey. I always said to her, 'Don't do so; for you can't make yourself any younger, and it is better when you are getting old to look old. Then people will do whatever you ask them! But however old you may be, if you look young, they'll say to you, "You are young enough and strong enough to do your own work yourself."'

My mother used to tell us stories too; but not so many as my granny. A few years ago there might be found several old people who knew those sort of stories; but now children go to school, and nobody thinks of remembering or telling them—they'll soon be all forgotten. It is true there are books with some stories something like these, but they always put them down wrong. Sometimes, when I cannot remember a bit of a story, I ask some one about it; then they say, 'There is a story of that name in my book. I don't know it, but I'll read.' Then they read it to me, but it is all wrong, so that I get quite cross, and make them shut up the book. For in the books they cut the stories quite short, and leave out the prettiest part, and they jumble up the beginning of one story with the end of another—so that it is altogether wrong.

When I was young, old people used to be very fond of telling these stories; but instead of that, it seems to me that now the old people are fond of nothing but making money.

Then I was married. I was twelve years old then. Our native people have a very happy life till we marry. The girls live with their father and mother, and brothers and sisters, and have got nothing to do but amuse themselves, and got father and mother to take care of them; but after they're married they go to live at their husband's house, and the husband's mother and sisters are often very unkind to them.

You English people can't understand that sort of thing. When an Englishman marries, he goes to a new house, and his wife is the mistress of it; but our native people are very different. If the father is dead, the mother and unmarried sisters live in the son's house, and rule it; his wife is nothing in the house. And the mother and sisters say to the son's wife, 'This is not your house—you've not always lived in it;—you cannot be mistress here.' And if the wife complains to her husband, and he speaks about it, they say, 'Very well, if you are such an unnatural son you'd better turn your mother and sisters out of doors; but while we live here, we'll rule the house.' So there is always plenty fighting. It's not unkind of the mother and sisters—it's custom.

My husband was a servant in Government House—that was when Lord Clare was Governor here. When I was twenty years old, my husband died of a bad fever, and left me with two children—the boy and the girl, Rosie.

I had no money to keep them with, so I said, 'I'll go to service,' and my mother-in-law said, 'How can you go with two children, and so young, and knowing nothing?' But I said, 'I can learn, and I'll go;' and a kind lady took me into her service. When I went to my first place, I hardly knew a word of English (though I knew our Calicut language, and Portuguese, and Hindostani, and Mahratti well enough) and I could not hold a needle. I was so stupid, like a Coolie-woman;[18] but my mistress was very kind to me, and I soon learnt; she did not mind the trouble of teaching me. I often think, 'Where find such good Christian people in these days?' To take a poor, stupid woman and her two children into the house—for I had them both with me, Rosie and the boy. I was a sharp girl in those days; I did my mistress's work and I looked after the children too. I never left them to any one else. If she wanted me for a long time, I used to bring the children into the room and set them down on the floor, so as to have them under my own eye whilst I did her work. My mistress was very fond of Rosie, and used to teach her to work and read. After some time my mistress went home, and since then I've been in eight places. One lady with whom I stayed wished to take me to England with her when she went home (at that time the children neither little or big), and she offered to give me Rs. 5000 and warm clothes if I would go with her; but I wouldn't go. I a silly girl then, and afraid of going from the children and on the sea; I think—'May be I shall make plenty money, but what good if all the little fishes eat my bones? I shall not rest with my old Father and Mother if I go'—so I told her I could not do it.

My brother-in-law was valet at that time to Napier Sahib,[19] up in Sind. All the people and servants were very fond of that Sahib. My brother-in-law was with him for ten years; and he wanted me to go up there to get place as ayah, and said, 'You quick, sharp girl, and know English very well; you easily get good place and make plenty money.' But I such a foolish woman I would not go. I write and tell him, 'No, I can't come, for Sind such a long way off, and I cannot leave the children.' I 'plenty proud' then. I give up all for the children. But now what good? I know your language—What use? To blow the fire? I only a miserable woman, fit to go to cook-room and cook the dinner. So go down in the world, a poor woman: (not much good to have plenty in head, and empty pocket!) but if I 'd been a man I might now be a Fouzdar.[20]

I was at Kolapore[21] at the time of the mutiny, and we had to run away in the middle of the night; but I've told you before all about that. Then seven years ago my mother died (she was ninety when she died), and we came back to live at Poona.

Not long afterwards my daughter was married there, and I was so happy and pleased I gave a feast then to three hundred people, and we had music and dancing, and my son, he so proud, he dancing from morning to night, and running here and there arranging everything; and on that day, I said, 'Throw the doors open, and any beggar, any poor person come here, give them what they like to eat, for whoever comes shall have enough, since there's no more work for me in the world.' So, thinking I should be able to leave service, and give up work, I spent all the money I had left. That was not very much, for in sending my son to school I'd spent a great deal. He was such a beauty boy—tall, straight, handsome—and so clever. They used to say he looked more like my brother than my son, and he said to me, 'Mammy, you've worked for us all your life, now I'm grown up I'll get a clerk's place and work for you. You shall work no more, but live in my house.' But last year he was drowned in the river. That was my great sad. Since then I couldn't lift up my head. I can't remember things now as I used to do, and all is muddled in my head, six and seven. It makes me sad sometimes to hear you laughing and talking so happy with your father and mother and all your family, when I think of my father, and mother, and brothers, and husband, and son, all dead and gone! No more happy home like that for me. What should I care to live for? I would come to England with you, for I know you would be good to me and bury me when I die, but I cannot go so far from Rosie. My one eye put out, my other eye left. I could not lose it too. If it were not for Rosie and her children I should like to travel about and see the world. There are four places I have always wished to see—Calcutta, Madras, England, and Jerusalem (my poor mother always wished to see Jerusalem too—that her great hope), but I shall not see them now. Many ladies wanted to take me to England with them, and if I had gone I should have saved plenty money, but now it is too late to think of that. Besides, it would not be much use. What's the good of my saving money? Can I take it away with me when I die? My father and grandfather did not do so, and they had enough to live on till they died. I have enough for what I want, and I've plenty poor relations. They all come to me asking for money, and I give it them. I thank our Saviour there are enough good Christians here to give me a slice of bread and cup of water when I can't work for it. I do not fear to come to want.[22]

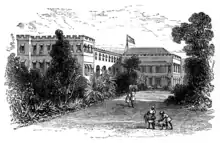

Government House,

Parell, Bombay, 1866.

GOVERNMENT HOUSE.

- ↑ Sergeant of native troops.

- ↑ The Duke of Wellington, Sir Thomas Monro, Sir John Malcolm, and Mr. Mountstuart Elphinstone.

- ↑ My children.

- ↑ Tent-pitcher.

- ↑ The Field Arsenal at Kirkee (near Poona).

- ↑ The battle which decided the fate of the Deccan, and led to the downfall of Bajee Row, Peishwa, and extinction of Mahratta rule. Fought 13th November 1817. (See Note A.)

- ↑ The following shows the Narrator's calculation of currency:—

1 Pie = ⅛ of an English penny.

3 Pie = 1 Pice.

4 Pice = 1 Anna.

16 Annas = 1 Rupee = 2 shillings. - ↑ A coarse cotton cloth.

- ↑ See Note B.

- ↑ Such work as is done by the Coolie caste: chiefly fetching and carrying heavy loads.

- ↑ O, my Father!

- ↑ The Pleiades.

- ↑ The Great Bear.

- ↑ The Southern Cross.

- ↑ The Milky Way. This is an ancient Christian legend.

- ↑ An intoxicating drink, made from the juice of the palm-tree.

- ↑ See Note C.

- ↑ A low caste; hewers of wood and drawers of water.

- ↑ Sir Charles Napier.

- ↑ Chief Constable.

- ↑ Capital of the Kolapore State, in the Southern Mahratta country.

- ↑ Anna Liberata de Souza died at Government House, Gunish Khind, near Poona, after a short illness, on 14th August 1887.