ORDER I. ANOURA.

(Frogs and Toads.)

In the adult or perfect condition, the form of these animals differs much from that common to the Amphibia, the body being short, broad, and flattened horizontally, and destitute of every vestige of a tail. There are four limbs, well developed, and furnished with toes, five on each foot, but the thumb of the fore foot is a mere tubercle; the posterior limbs are longer than the others, and are formed for leaping. The ribs are totally wanting; the vertebræ or joints of the spine are few and soldered together. The tympanum or drum of the ear is exposed.

In the tadpole condition, the form is fish-like, the body being lengthened, compressed, and terminating in a long thin tail; there are no limbs, these being developed in the process of metamorphosis; the water is the medium which the animal in this its infancy inhabits, in which it swims with ease, by the lateral undulation of its oar-like tail. Respiration is performed by gills or branchiæ alone, which project on each side of the neck in the form of little tufts. As the period of the change approaches, these are gradually withdrawn into the chest, and the animal becomes an air-breathing Frog or Toad, more or less terrestrial in its habits.

The eggs are enveloped in a clear and tenacious jelly, and are laid either in long strings, or in large masses; they are fertilized externally, in the process of deposition, which always takes place in the water.

The head of these animals is very large, but the cavity of the skull is very small; and yet the brain is scarcely sufficient to fill it. The gape is enormous.

The Anoura are distributed over the whole habitable globe; but they abound most in America, while Africa presents us with very few. These facts are sufficiently explained by the abundance of water in the one continent, and by the scarcity of it in the other. The Order contains four Families, Ranadæ, Hyladæ, Bufonidæ, and Pipadæ.

Family I. Ranadæ.

(Frogs.)

The Frogs proper are distinguished from the Toads by having small teeth in the upper jaw; most of the species have also teeth in the palate, or rather pointed processes forming a part of the bones to which they are attached, as in the case of certain fishes. From the Tree-frogs they are distinguished by having the toes ending in blunt points, scarcely or not at all dilated, and by terrestrial and aquatic habits. They have always four toes on each anterior foot, and five on the posterior, which are commonly united by a broad swimming membrane, like those of web-footed birds. At the base of the first finger of the hand, there is generally a prominence, more or less obvious, which proves, on dissection, to be the rudiment of a thumb, and at the outer edge of the ankle of the hind foot there is for the most part a tubercle, which in some genera is expanded into a large oval disk with free edges; this tubercle is analogous to one of the little bones of the human ankle, and is not, as has been supposed, the rudiment of a sixth toe.

The motions of the Frogs are lively, and the muscular power displayed by them very great, particularly in swimming and leaping. “The muscles of the abdomen,” as Mr. Broderip observes, “are more developed than in the other reptiles, offering, in this particular, some analogy to the abdominal structure of the Mammifers. But it is in the disposition of the muscles of the thigh and legs, in the Frogs and other Anourous Batrachians, that the greatest singularity is manifested. These, whether taken conjointly or singly, present the greatest analogy with the muscular arrangement of the same parts in man. We find the rounded, elongated, conical thigh, the knee extending itself in the same direction with the thigh-bone, and a well-fashioned calf to the leg. It is impossible to watch the horizontal motions of a frog in the water, as it is impelled by these muscles and its webbed feet, without being struck by the complete resemblance in this portion of its frame to human conformation, and the almost perfect identity of the movements of its lower extremities with those of a man making the same efforts in the same situation. By the aid of these well-developed lower limbs, and the prodigious power of their muscular and bony levers, a Frog can raise itself in the air to twenty times its own height, and traverse, at a single bound, a space more than fifty times the length of its own body.”

The food of the Frogs in the tadpole condition consists of decaying vegetable matter, though they do not refuse to prey upon animal substances also. In the adult state they feed on insects, slugs, &c., in the taking of which the tongue is principally employed. This organ, which is soft and fleshy, and covered with a glutinous secretion, is fixed to the inner part of the front of the jaw, so that when at rest its tip points backwards towards the throat. When the Frog takes its prey, the tongue, observes Mr. Martin, “becomes considerably elongated, and turns on the pivot of its anterior fixture, being reversed in such a manner that the surface which was undermost when the tongue was lying in a state of repose in the mouth, is now the uppermost, the original position being regained, when it turns on its pivot back again into the mouth. The rapidity with which the Frog or Toad launches this organ at insects or slugs is extraordinary, insomuch that the eye can scarcely follow the movement; never is the aim missed; the prey touched by the tongue adheres firmly, the viscid saliva being very tenacious, and is instantaneously carried to the back of the mouth and swallowed.

“We have often presented slugs on bits of straw or stick to Toads, and watched with surprise the sudden disappearing of the prey, which seemed to vanish from the stick as if by magic.”[1]

The Frogs are endued with considerable powers of voice; their efforts, it is true, are not very musical; a hoarse guttural croaking is the sound with which we are most familiar, but some foreign species utter various other discordant noises, such as shrieks long-protracted, and intolerably shrill and piercing, whistlings, snorings as of a person in oppressed slumber, or the deep bellowings of a bull.

In temperate countries they become torpid during winter, retiring on the approach of cold weather into the mud at the bottom of ponds, where multitudes huddle together in numerous assemblages. The mild air of spring awakens them from their death-like sleep, when they separate, emerge from their retreat, and soon make the shores of our waters vocal, if not musical, with the pertinacity of their sexual call.

Genus Rana. (Linn.)

The skin in this, the typical genus, is smooth; the hinder legs are very long, muscular, and formed for leaping; the toes of the hind feet are connected by a web; there are teeth on the upper jaw, and on the palate; the gape is very wide; the tongue, broad, soft, notched at the extremity, is folded back, the anterior portion lying ordinarily on the posterior; the eyes are brilliant and prominent, and elevated above the forehead.

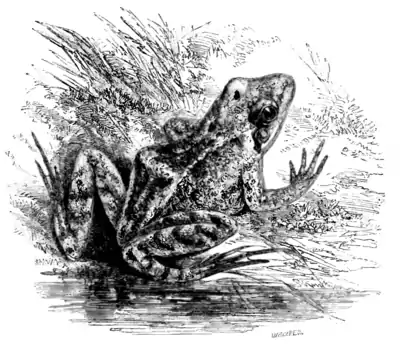

The Common Frog (Rana temporaria, Linn.) is familiar to every child. Every rivulet and river, every lake, pond, and pool, every stagnant or running ditch by the road-side, and even the little collections of rain-water that lie in the gravel-pits of the common, are pretty sure to be tenanted by this vigorous and graceful swimmer, or by its black and wriggling tadpoles. When full grown the Frog is rather more than two inches and a half in length; it varies much in colour and markings, but is commonly of a yellowish brown, sometimes greenish or reddish, irregularly spotted with dark brown patches,

FROG.

which on the limbs take the form of transverse bands: there is generally an oblong patch of brown behind each eye, and a pale line down each side: the under parts are yellowish white.

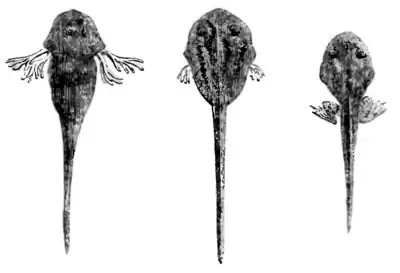

Early in spring the Frog deposits its eggs at the bottom of water; these resemble black dots distributed at equal distances throughout a large mass of transparent jelly. After a while the mass rises to the surface. In about a month after the deposition, in this country, but much sooner in warmer climates, the little Tadpoles are hatched. They appear to consist of an enormous head and a long, thin, vertically flattened tail; from the hinder part of the head, on each side, are seen to project two minute tufts, divided into branched leaflets. These are the branchiæ or gills, by means of which oxygen is separated from the water for the renewal of the vital power of the blood. These tufts rapidly enlarge, and soon attain their greatest development, in which state they form, as Mr. Bell assures us, one of the most charming objects for microscopic observation which can be conceived, and to view which a very high power is not necessary nor even desirable. The current of the blood poured in regular pulsations at each contraction of the heart, passes up each stem or main branch of the branchiæ, and a distinct stream is given off to each leaf; it is propelled to the extremity, and

TADPOLES.

then returns down the opposite sides in the most regular manner, and the parts are so transparent that every globule of blood is distinctly and beautifully visible.[2]

The branchial tufts now begin to diminish, while the Tadpole increases in bulk, until at length the limbs bud forth and assume their form and toes, the hinder pair being developed first. The tail is now gradually absorbed, the absorption commencing at the tip and proceeding towards the base until the last trace has disappeared. The gills are by this time so much reduced as to be withdrawn beneath the skin, and are no more visible; the eyes and mouth are fully formed; the colour has changed to an olive-green, spotted with yellow on the under parts; and, in short, the animal is no longer a Tadpole, but a little Frog.

The respiration is now carried on by means of large cellular lungs; but the action of breathing is not performed as in most other Vertebrata, by alternate contraction and dilatation of the chest, for the Frog has no ribs, by the depression of which to enlarge the thoracic cavity,—but by the actual swallowing of the air, the element being forced down the windpipe into the lungs, by an action perfectly similar to that by which food is forced down the gullet into the stomach.

But there is another agent employed in the respiration of these animals beside the lungs, namely, the whole surface of the skin. Numerous and careful experiments have proved that the blood is purified, and the vital functions go on for a considerable time, after all access of air to the lungs has been cut off, and even (by an experiment, the wicked cruelty of which we cannot mention without reprobation) after the lungs had been totally cut out. It is necessary, however, that the skin should be maintained continually moist; for if it become dry, its action ceases, and death is the speedy result. “But,” remarks Professor Bell, “as the frog is frequently exposed to a dry atmosphere, it is essential that there should be some provision made for a constant supply of moisture to the skin. This is effected by a secretion of fluid from the surface itself. The extent of the skin is, however, so great that the whole internal moisture of the animal would speedily be exhausted, unless a reservoir were provided for an extraordinary demand; and I now proceed to shew what this reservoir is, and by what means it is replenished. Every one knows that when a Frog is hastily seized, or even quickly pursued, it voids a considerable quantity of water, which is generally but erroneously, supposed to be the urine. This water is limpid and pure, containing no traces of the usual component elements of the urinary secretion. It is contained in a sac, which has also been mistakenly believed to be the urinary bladder. This is the reservoir to which I have alluded. When, therefore, the frog is happily placed in a damp atmosphere, or in the water, the skin absorbs a quantity of water, which there is every reason to believe is secreted into the bladder just mentioned, where it is kept in store until the dryness of the skin requires a supply for the purpose of respiration, when it is again taken up, and restored to the surface, by which it had been first absorbed.”[3]

The Frog is capable of being tamed, and of discerning those who treat it kindly. If kept in a garden, it proves a very useful inhabitant, by its services in devouring noxious insects, and particularly the small species of slug which is so destructive to vegetation. The number of these which a single Frog will devour is truly surprising.

Family II. Hyladæ.

(Tree-frogs.)

This is the most numerous in species of all the Families of the Amphibia, and the one which deviates most in its manners from the rest. The Tree-frogs reside habitually among the foliage of trees, among which they hop and leap almost with the agility of the birds that tenant the groves conjointly with them. They are able to cling to the leaves on which they alight, with exact precision, and to walk on them in all positions, and even on their under surfaces, without falling off, just as a fly alights on the ceiling of a room, and rests or crawls there. The smoothness of the leaves, or other surfaces on which they rest, offers no impediment to the security of their position, for they do not derive their power from the inequalities of the surface. “The monkey grasps with its paws the perch on which it rests; the bird with its claws; the snake twines itself around the branch; the iguana uses its long toes and hooked nails; the chameleon holds the bough tight between its vice-like toes; but the foot of the Tree-frog acts differently from the foot of these animals: it is not a grasping organ, nor is it furnished with claws for clinging; but it is provided with suckers, analogous to those we have noticed in the foot of the Gecko.”[4] Each toe, both of the fore and hind feet, is dilated at the tip into a circular pallette or pad, varying in size in different genera: these little cushions are, it is true, moistened with a glutinous fluid, as is the whole surface of the body; but we believe that this viscidity is not, as has been supposed, the agent by which the animal so powerfully adheres against gravity; but that the pallettes act as suckers, being sustained in their position by the pressure of the atmosphere, a vacuum being produced beneath them, or removed at the creature’s will.

The colours of the Tree-frogs are various, and are often brilliant and beautiful; like many other Reptiles they have the faculty of changing their hues to an extent that often affords them protection, by rendering them difficult to be discerned. They are very numerous in the damp woods of tropical America, residing habitually by day in the concealment afforded by the huge Bromeliaceæ or Wildpines, and other parasitical plants that grow in tufts on the trunks and branches of great trees, the sheathing bases of whose leaves not only afford them umbrageous bowers in which to dwell, but also form reservoirs in which the rain-water collects, and thus provide the moisture without which they would soon expire. The under-surface of the bodies of these arboreal Frogs is very different from that of the terrestrial species; the skin, instead of being smooth, is covered with granular glands pierced by numerous pores, through which the dew or rain spread on the surface of the leaves is rapidly absorbed into the system, and reserved to supply the moisture needful for cutaneous respiration, as already explained. In the night, they are active and vociferous, and the woods in the tropics then resound with the various sounds emitted by these creatures. Some utter a pleasing chirp, or clear whistle, like the voice of a bird; others produce a ringing shriek, so loud and piercing as to be almost unbearable, while yet others supply the bass of this nocturnal concert, groaning and snoring in great variety of deep, hollow, guttural sounds. These noises reiterated with incessant pertinacity, through the livelong night, mingled with the shrill crinking of locusts and Cicadæ, quite banish sleep from a stranger’s eyes; but habit, as in other things, soon familiarises the ear to these discordant noises, and they cease to be perceived. These cries are uttered only by the males; which are furnished beneath the throat with a dilatable skin, capable of being inflated into a tense globose bladder, during the emission of the sound.

The prey of the Hyladæ consists of insects and similar small creatures, which are taken by the instantaneous projection of the tongue. Their upper jaw is furnished with teeth like that of the Frogs, but the manner in which they are arranged differs in different genera. The form of the tongue also varies; in some it is forked, in others it is heart-shaped, and in others it is long and ribbon-like. The toes are for the most part webbed, but in several genera they are free, and in one they are fringed with a free membrane on each side; in one genus the first toe is opposible to the others, thus forming a sort of hand.

The early history of the Tree-frogs does not differ materially from that of their humbler terrestrial brethren. The eggs are laid in the water, in which the Tadpoles spend their existence; and in temperate climates the perfect animals resort to the same element to spend the winter in a torpid insensibility.

The sixty-four species which MM. Duméril and Bibron enumerate as belonging to this Family are thus distributed:—one is found in southern Europe; five are peculiar to Africa; eight to Asia; ten to Australasia and the Indian Archipelago; and thirty-seven to America. Of three species, the native locality is unrecorded.

Genus Hyla. (Laur.)

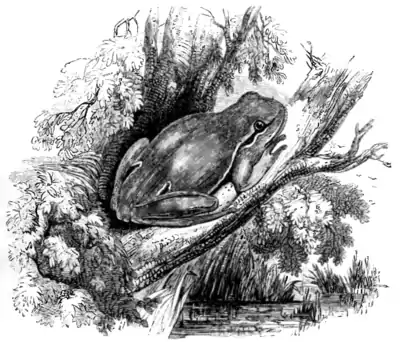

The extreme elegance and beauty of the European Tree-frog (Hyla viridis, Laur.) have made it a general favourite wherever known. It is small and of slender proportions; the upper parts are of a delicate green, the inferior parts white; on each side of the body runs down a stripe of yellow bordered with violet or purple, extending along the limbs. It is spread over the whole of southern Europe, extending also into North Africa, but is not a native of Great Britain. During winter it remains torpid at the bottom of ponds, but through the balmy months of summer this beautiful little creature resides in trees, principally resorting to the higher branches, where it leaps to and fro, or lurks among the foliage in search of insects. These it captures with much dexterity, stealing softly towards a vagrant fly or beetle, as a cat does upon a mouse, its green hue rendering its approach among the quivering leaves undistinguishable, till, being arrived at a proper nearness, it suddenly launches and retracts its tongue with a lightning stroke, and the unsuspecting insect vanishes within its mouth.

TREE-FROG.

The croak of the Tree-frog is very loud and hoarse, so as to be heard at a great distance. The commencement of this note is the signal for all to join that are within hearing, and a chorus is formed that is said to resemble the baying of a pack of hounds. During the emission of the sound the skin of the throat is inflated so as to form a sphere nearly as large as the head.

Some interesting observations on the respiration of these animals are recorded by Dr. Townson. He kept his Tree-frogs in a window, and appropriated to their use a bowl of water, in which they lived. They soon grew quite tame; and to two that he kept a considerable length of time, and were particular favourites, he gave the names of Damon and Musidora. In the hot weather, whenever they descended to the floor, they soon became lank and emaciated. In the evening they seldom failed to go into the water, unless the weather was cold and damp; in which case they would sometimes remain out for a couple of days. When they were out of the water, if a few drops were thrown upon the board, they always applied their bodies as close to it as they could; and from this absorption through the skin, though they were flaccid before, they soon again appeared plump. A Tree-frog that had not been in water during the night was weighed, and then immersed: after it had remained about half an hour in the bowl it came out, and was found to have absorbed nearly half its own weight of water. From other experiments on Tree-frogs, it was discovered that they frequently absorbed, by the under-surface only of their bodies, nearly their whole weight of water. These animals will even absorb moisture from wetted blotting-paper. Sometimes, with considerable force, they eject water from their bodies, to the quantity of a fourth part or more of their own weight.

Both Frogs and Toads will frequently suffer their natural food to remain before them untouched, yet if it make the smallest motion, they instantly seize it. A knowledge of this circumstance enabled Dr. Townson to feed his favourite Tree-frog, Musidora, through the winter. Before the flies, which were her usual food, had disappeared in autumn, he collected for her a great quantity, as winter provision. When he laid any of them before her, she took no notice of them; but the moment he moved them with his breath, she sprung upon and ate them. Once when flies were scarce, the Doctor cut some flesh of a tortoise into small pieces, and moved these by the same means. She seized them, but the instant afterwards rejected them from her tongue. After he had obtained her confidence, she ate from his fingers dead as well as living flies. Frogs will leap at a moving shadow of any small object; and both Frogs and Toads will soon become sufficiently familiar to sit on the hand, and be carried from one side of the room to the other in order to catch flies as they settle on the wall. At Gottingen, Dr. Townson made them his guards for keeping these troublesome creatures from his dessert of fruit, and they acquitted themselves to his satisfaction. He has even seen the small Tree-frogs eat humble bees, but this was never done without some contest. The Frogs were in general obliged to reject them, being incommoded by their stings and hairy roughness; but in each attempt the bee was farther covered with viscid matter from the Frog’s tongue, and, when sufficiently covered with this, it was easily swallowed.[5]

Family III. Bufonidæ.

(Toads.)

The Toads are totally without teeth, both in the jaws and in the palate; the body is thick and swollen, and the skin is set with warts or tubercles; behind each eye is a glandular protuberance, studded with pores, from which a milky secretion exudes; the head is large and flat on the top; the hinder limbs are not much longer than the fore, and consequently their powers of leaping are but small. They habitually crawl, and when they jump, it is with little agility, and only to a short distance. In the tadpole state they inhabit the water, and resemble the members of the preceding Families; but after their metamorphosis, they are much less dependent on the presence of that element, rather affecting dry situations. They are for the most part nocturnal in their habits, crawling about in the twilight and darkness in search of insects and slugs, but retiring during the day into holes in the earth, beneath stones, roots of trees, and other obscure retreats.

Some of the foreign Toads are marked by curious peculiarities of structure. One genus has the back armed with a long dorsal shield; another has the muzzle set with beards: some have only four toes on the hind foot; others have on the same foot two large oblong tubercles in addition to the five normal toes.

Geographically the Toads are said to be thus distributed:—Europe possesses four species, which are not, however, peculiar to it; Asia nine; Africa two; Australia one; and America seventeen; and there are four or five whose locality is unrecorded. This enumeration, however, must be greatly under the mark; as many species have been lately added to those previously known.

Genus Bufo. (Laur.)

The characters by which the true Toads are distinguished are thus enumerated by Professor Bell. Body inflated, skin warty, parotids (or glands behind the eyes) porous, hind feet of moderate length, toes not webbed, jaws without teeth, nose rounded.

Eighteen species of this genus are recorded, of which the best known is the Common Toad (Bufo vulgaris, Laur.), which is spread over Europe, Asia, and North Africa, being found from Great Britain to Japan. It is nearly three inches and a half in length, of an unpleasing form and aspect; the body puffed and swollen, covered with warts, which are larger on the upper parts, smaller, but more numerous beneath. The colours are commonly a dull lurid blackish hue above, with the warts brown; and a dirty yellowish white beneath.

The Toad is not poisonous in the sense in which the Viper is; but the popular prejudice is not wholly without foundation, which attributes “sweltered venom” to this animal. On the back and sides are situated many glands in the skin, which secrete a fetid and acrid matter. This substance exudes from the glands on pressure, "in the form of a thick yellowish fluid, which, on evaporation, yields a transparent residue, very acrid, and acting on the tongue like extract of aconite. It is neither acid nor alkaline; and since a chicken inoculated with it, received no injury, it does not appear to be noxious when absorbed, and carried into the circulation![6]"

TOAD.

The prey of the Toad is the same as that of the Frog,—insects of all kinds, slugs and earthworms; and hence it is a useful inhabitant of a garden, in which it may be often kept with more facility than the Frog, from its indifference to water, which is needful to the comfort of the Frog. It takes its food in the same manner, but refuses that which is not alive, and even in actual motion. It is sluggish in its motions, neither leaping nor running, its pace being a kind of crawl. On being alarmed, it stops, swells its body, and on its being handled, a portion of the acrid secretion exudes from the glands, and a quantity of pure water, alluded to in our account of the Frog, is suddenly discharged from the internal reservoir.

Like the other Amphibia, the Toad casts its skin at uncertain periods, after which its colours are much brighter than before. The outer skin divides in a line, extending down the middle of the back and of the belly, and is gradually pushed down in folds towards each side, until it is detached, when it is pushed by the two hands into the mouth in a ball, and swallowed at a single gulp. The hands are used in the same manner, to push into the mouth earthworms, which in their writhing, twist about the animal’s muzzle and head.

The Toad is more easily tamed than the Frog: Professor Bell mentions a very large one which would sit on one of his hands, and eat from the other; and Pennant in his “British Zoology” has immortalized a pet Toad of one of his correspondents in a narrative, which is interesting in another respect also, as shewing the great longevity of this Reptile.

“Concerning the Toad,” writes Mr. Arscott, “that lived so many years with us, and was so great a favourite, the greatest curiosity was its becoming so remarkably tame. It had frequented some steps before our hall door, some years before my acquaintance commenced with it, and had been admired by my father for its size (being the largest I ever met with), who constantly paid it a visit every evening. I knew it myself upwards of thirty years; and, by constantly feeding it, brought it to be so tame, that it always came to the candle and looked up, as if expecting to be taken up and brought upon the table, where I always fed it upon insects of all sorts. It was fondest of flesh-maggots, which I kept in bran: it would follow them, and when within a proper distance, would fix its eyes, and remain motionless for near a quarter of a minute, as if preparing for the stroke, which was an instantaneous throwing of its tongue at a great distance upon the insect, which stuck to the tip by a glutinous matter. The motion is quicker than the eye can follow. I cannot say how long my father had been acquainted with the Toad before I knew it; but when I was first acquainted with it, he used to mention it as ‘the old Toad I have known for so many years.’ I can answer for thirty-six years.” The end of this Toad was somewhat tragical. A tame Raven seeing it at the mouth of its hole, pulled it out, and before help could come, destroyed one of its eyes, and so injured it, that, though it survived a year, it never enjoyed itself again, nor could take its prey with the same precision as before. Up to that accident it had seemed to be in perfect health.

Family IV. Pipadæ.

In this Family, which consists of a single genus confined to South America, the tongue is entirely wanting. The body is flattened and very broad; the head also is large, flat, and somewhat triangular; the tympanum is concealed, the toes are divided into star-like points.

Genus Pipa. (Laur.)

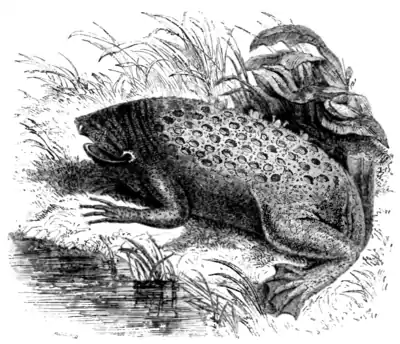

The large triangular head in this singularly uncouth reptile, bears a distant resemblance to that of a hog, having the muzzle prolonged into a sort of tube in which the nostrils terminate; the eyes are minute and situated on the upper surface of the head, near the margin; the eyelids are merely rudimentary, incapable of covering the eyes. There is no tongue, nor any teeth either in the jaws or palate, nor any external trace of the great parotid glands, so conspicuous behind the eyes of our common Toad. The gape of the mouth is very wide, the upper jaw is furnished with a little barbule, which depends on each side, and a cutaneous appendage, somewhat like a little ear, is affixed to the angle of the mouth. The fore feet are furnished with four toes each, which are long and slender, and divided at their tips into four distinct points, each of which, when examined with a microscope, is found to be obscurely divided almost in a similar manner. The hind limbs are short and stout, the feet large with five toes, united by broad membranes. The skin differs from that of the Amphibia generally, being covered with minute hard granules, among which are scattered small conical tubercles of a horny substance. The male has an enormous larynx, which takes the form of a triangular bony box, within which are two moveable bones, which can close the divisions of the

PIPA.

windpipe, and thus influence the intonation of the voice.

Two species of this singular reptile are known, of which we shall adduce only the Surinam Toad (Pipa Surinamensis, Daud.). This is much larger than our Toad, growing to six or eight inches in length; it is of a dark brown colour, covered with reddish tubercles. It has a granulated back, with three longitudinal ranges of larger granules. It inhabits cellars and obscure corners of houses in Guiana, and other parts of South America, where, notwithstanding its repulsive aspect, its flesh is eaten with relish by the negroes.

The continuation of the species in this Reptile is attended with phenomena no less extraordinary than its figure. The female presents at certain times the strange spectacle of a great number of young ones in various stages of development, lodged in or proceeding from cells dispersed over the upper surface of her body. It was at one period supposed that the eggs were produced in these cells, and not deposited in the usual manner; but it is now known that the female deposits her spawn at the edge of some stagnant pool, where the male, collecting it with great care, places it on the broad and flat back of his mate. The presence of the ova is believed to produce a sort of suppuration, whereby a number of pits or circular cells are formed in the substance of the skin; these are about half an inch in depth and a quarter of an inch in diameter. Each of these having received an egg, closes over it, and thus the skin resembles the closed cells of a honey-comb. The cells are formed only in the substance of the skin, which is thickened for the purpose, and do not penetrate to the muscles beneath. The true skin is indeed separated from the muscles by large reservoirs of fluid.

The female Pipa, having received her burden, retires into the water; and in due time the enclosed eggs are hatched, and the young tadpoles pass their stage of existence within the cells, from which they do not emerge until they have passed their metamorphosis, and assumed the form of the adult animal, though very small. This takes place in about eighty-two days from the time when the eggs were first placed on the back of the mother. Those cells which occupy the middle part of the back are first evacuated, doubtless because they were first occupied. The mother, relieved of her charge, now resorts to the land, where, it is reported, she frees herself from her honey-combed skin by rubbing her body against a stone.

- ↑ “Pict. Mus. ii.” 126.

- ↑ “British Reptiles” 96.

- ↑ “British Reptiles,” 79.

- ↑ “Popular History of Reptiles,” 303.

- ↑ “Bingley’s Animal Biography,” iii. 162.

- ↑ Dr. Davy, quoted in "British Reptiles," 113.