ORDER I. ACANTHOPTERYGII.

(Spiny-finned Fishes.)

The skeleton in this large and very natural Order is composed of bone; the first rays (counting from the head backward), of the dorsal fin, of the pectorals, and of the anal, and, generally the first ray of the ventrals are unjointed, inflexible, and spinous. When there is more than one dorsal, the anterior is entirely filled with spinous rays. In some cases, as in the common Sticklebacks, the spinous rays are unconnected by a common membrane, and form free spines. The ventrals are, for the most part beneath the pectorals, or even in advance of them. The body is clothed with scales formed of successive laminæ or layers of horn-like, unenamelled bone, which have their free hinder margin cut into teeth. The swimming-bladder is not furnished with an air-duct leading into the gullet.

Nearly two-thirds of the species belonging to the whole Class of Fishes are found in this Order, which are scattered over all parts of the world, both in fresh and salt waters. Many of them are distinguished for elegance of form and beauty of colour; nearly all are fit for food, and some, as the Mackerel family, including the Tunny, support important fisheries.

The form of the dorsal fin is subject to much variation in this Order. Nearly half of the species have it divided into two, a spinous and a flexible one; a large portion of the remainder have the division indicated by a depression in the margin, or a cleft more or less deep, though the membrane is continuous. In some cases, as already intimated, the first dorsal is represented by a few detached spines, either quite destitute of membrane, or each furnished with its own.

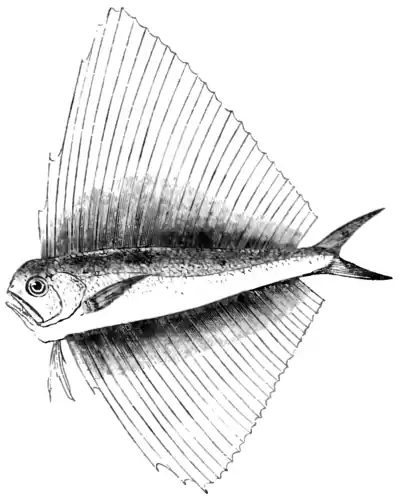

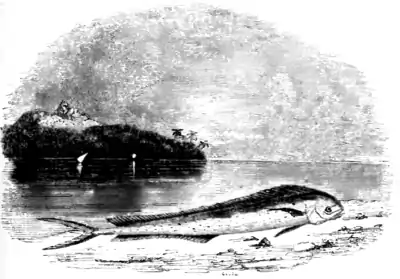

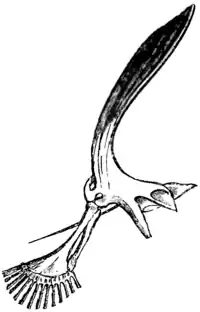

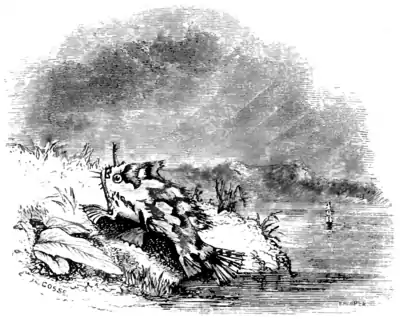

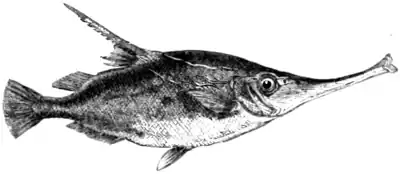

In some of the Gurnards one or more of the spinous rays are greatly prolonged beyond the membrane; in the Dory the membrane is prolonged between the spines into lengthened threads; in the Sword-fish, the Opah, and the Gemmeous Dragonet, the anterior portion is elevated like a sail; while in the singular genus Pteraclis, of the American seas, figured on the opposite page, both the dorsal and the anal are so immense as to give to the vertical outline of this fish somewhat the form of a butterfly with expanded wings. The Gurnards have the pectorals unusually developed, so that some foreign species can use them as organs of flight through the air. Examples of this, in a less degree, may be observed in our native species, which have these fins very large, and several long supplementary rays in front of them.

The following seventeen Families of Acanthopterygian Fishes are enumerated in the synopsis of the Prince of Canino, who gives the affixed number of species known (in 1831) to belong to each.

| SP. | ||

| 1 | Percadæ | 483 |

| 2 | Sphyrænadæ | 15 |

| 3 | Mullidæ | 42 |

| 4 | Trigladæ | 164 |

| 5 | Sciænadæ | 231 |

| 6 | Sparidæ | 158 |

| 7 | Mænadæ | 43 |

| 8 | Chætodontidæ | 157 |

| 9 | Scombridæ | 262 |

| 10 | Cepoladæ | 14 |

| 11 | Teuthididæ | 60 |

| 12 | Ophiocephalidæ | 40 |

| 13 | Mugilidæ | 52 |

| 14 | Gobiadæ | 173 |

| 15 | Lophiadæ | 40 |

| 16 | Labridæ | 283 |

| 17 | Fistulariadæ | 15 |

| Total 2232 | ||

Family I. Percadæ.

(Perches.)

A vast assemblage of species, amounting to about one-seventh of the whole Class, is seen by the preceding table to be comprised in this Family. They are, for the most part, marine fishes, though the typical genus, which gives a name to the Family, inhabits fresh waters. The form is generally long-oval; the body is covered with scales, the surface of which is more or less rough, and the free margins of which are notched like the teeth of a comb; the scales do not extend upon the fins; the gill-cover (operculum), and the gill-flap (preoperculum), are variously armed with spines, and cut into teeth at their margins. Both the upper and lower jaw are set with teeth, besides which, the bones of the palate and the vomer (or middle ridge of the roof of the mouth) are furnished with them, so that there are five rows of teeth above, and two below. In general, all the teeth are fine, and set in close array, so as to bear a remote resemblance, in appearance, to the pile of velvet. The branchiostegous rays, or the slender arched bones of the membrane that closes the great fissure of the gills beneath, vary in number from five to seven. The ventral fins are, in general, placed under the pectorals; the dorsal is either double or depressed in the middle.

So immense a Family cannot but comprise several varieties of form, which, while agreeing in the important characteristics that distinguish these Fishes from those of the other Families, differ considerably in subordinate points. Five leading types are seen to subsist, around which so many groups, called Sub-Families, are arranged. These we shall briefly notice.

The true Perches (Percina) have two distinct dorsal fins, with the membrane which connects the rays semi-transparent and nearly colourless. The pectorals and ventrals are obtuse, or somewhat rounded; the former contain each five soft rays; the latter are placed beneath the pectorals. The form of the body is oblong; the scales are comparatively large; the mouth is wide, and furnished with short and small teeth much crowded, without any larger pointed teeth, resembling canines, at the sides. The genus Lucioperca, as its name, signifying Pike-perch, expresses, has the structure of a Perch with the form and appearance, and even the ferocity of a Pike; while the Diploprion, of the coast of Java, and still more the Enoplosus of Australia, might readily be mistaken for a true Chætodon, having not only the short, high, compressed form of that genus, with its tall fins, but the small mouth, and delicate teeth, and even the characteristic colours and markings of Chætodon, the former being yellow, with a black vertical band through the eye, and another across the body, and the latter silvery white, with seven or eight vertical bands. Yet in each case the fins are destitute of scales, the gill-plates are spinous, and all the essential characters of true Perches, are exhibited.

The Serrans (Serranina), a very numerous sub-family, are distinguished by having the two dorsals united into a single fin, the place of the division being marked, however, by a depression more or less deep in the outline. They have for the most part a larger acute tooth on each side of the mouth, resembling the canines of Mammalia. Their colours are generally beautiful, and frequently arranged in bands and spots, extending upon the fin-membranes. They are all marine, and nearly all tropical, but some are found in the Mediterranean, and two species have been met with on the coast of Cornwall.

The third Sub-family, named Holocentrina, or the Mailed Perches, are still more beautiful than the preceding. They are usually of small size, but of great brilliancy of colouring, the prevailing hues being various shades of red, ranging from the richest crimson to a gorgeous orange or golden hue. They are all clothed with bony, generally toothed, scales, which in some of the genera form a close impenetrable coat of mail. Not a single British example of this group is known, they being almost confined to the tropical seas.

In the Jugular Perches (Percophina) the ventrals are placed beneath the throat, considerably in advance of the line of the pectorals. The head is pointed, and the lips generally thickened, as in the Wrasses (Labridæ); the body is remarkably lengthened. To this group belong some common British Fishes known as Weevers (Trachinus, Linn.), remarkable for the enormous length of the second dorsal and the anal, and for the formidable spines with which they are armed. These spines are the rays of the first dorsal, which are very sharp and strong, and a long lance-like spine on the gill-flap; wounds inflicted with which are believed to be poisoned. Whether this be so or not, it is certain that they speedily exhibit symptoms of strong inflammation, attended with acute pain, extending to a great distance from the part lacerated. The Weever appears to be perfectly aware of the power of its weapons; it buries itself in the mud or sand at the bottom, with its mouth, which opens upwards, exposed. As it thus lies in wait for any passing prey, it may often be touched by an unconscious assailant, when instantly the little warrior strikes forcibly with his pointed spears, upwards and to each side. Pennant says of the Little Weever, that he has seen it direct its blows with as much judgment as a fighting-cock.

The last Sub-Family, the Helotina, "constitute," says Cuvier, "a group formed, as it were, to make naturalists despair, by showing how Nature laughs at what we deem characteristic combinations;" the genera possessing mutual relations sufficient to forbid their separation, and bearing a great resemblance to the other members of the common Family; while the species exhibit in the subordinate characters, such as the number, form, position, and even presence of the teeth, much diversity. None, however, have more than six gill-arches; they have no scales on the head, muzzle, or jaws; the dorsal spines, when depressed, fall into a longitudinal groove on the back; and the air-bladder is always divided into two distinct sacs, connected by a narrow neck. These too are chiefly inhabitants of warm latitudes, some marine, and some fluviatile; they do not possess much attractiveness of appearance, their colour being, in general, silvery grey, marked with dusky longitudinal lines.

Genus Perca. (Linn.)

The distinctive characters of the Perches proper are two dorsal fins quite separated, of which the fore one possesses only spinous rays, the hinder only flexible or soft ones. The tongue is smooth; the mouth is armed with teeth, situated in both jaws, in front of the vomer or middle

ridge of the palate, and on the bones of the palate itself; the fore gill-flap (preoperculum) is notched below, and has its hind edge cut into small teeth like those of a saw; the gill-cover (operculum) is bony, and terminates in a flattened spiine pointing backwards. The gill-arches are seven. The scales are rough, hard, and detached with difficulty.

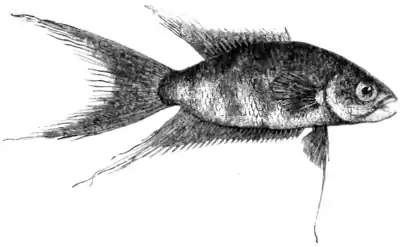

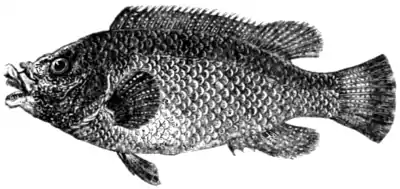

The Common Perch (Perca fluviatilis, Linn.) is well known, not only to the angler, but to almost every country child; for it inhabits most of our lakes and rivers, especially where the banks are steep, and is so bold as to bite at nearly any bait. Hence this is usually the first fish that rewards the infant angler’s enterprise.

It scarcely yields to any of our native Fishes in

beauty; its form is compact and powerful, and its colours attractive, especially when seen through the clear water in which it is playing. Its aspect, however, when drawn from the water, is determined and almost ferocious, particularly when the high and spinous dorsal-fin is stiffly erected.

The excellence of the Perch, as a table fish, is generally acknowledged; in this respect, perhaps, it is exceeded by none of our fluviatile species, with the exception of the Trout and the Salmon. Perch of five pounds are not uncommon, and they have been known to attain even double this weight. A Fish of large size needs good tackle as well as skill in the angler, for it is powerful in proportion to its size. When Perch run large, a minnow, roach, or gudgeon is a successful bait; but the more usual baits are worms and gentles; fresh-water shrimps are much used by those who fish for Perch in the docks of London, where these Fishes are both fine and plentiful. In still water, as that of lakes or ponds, the bait should be allowed to float in mid-water; in rivers, nearer the bottom. In March, the Perch deposits its spawn, after which it will afford good sport to the end of October; a cool day with a fresh breeze to ruffle the surface, being most propitious.

The readiness with which this beautiful fish is taken is partly due to its voracity, in which it almost equals the ravenous Pike; when hungry indeed, it will seize almost any object that is presented to it. A writer in the New Sporting Magazine, says that he has repeatedly taken a Perch with no other bait than a portion of the gills of one just captured, accidentally remaining on the hook, the line having been carelessly allowed to drop into the water while a fresh bait was being selected. "Red seems an attractive colour to them, and whether it presents itself in the blood of one of their former companions, or the hackle of a cock, is a matter of perfect indifference."[1]

There are plenty of very fine Perch all along the Thames, but the most favourite resorts for these fish, are the deeps near Twickenham, either above or below the lock at Teddington, and in some deep holes about halfway between the lock and Hampton Wick; Perch have been taken in these places frequently as large as four pounds' weight each.

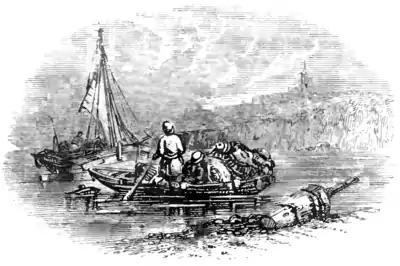

Very large Perch and Trout are taken in the rivers of Ireland, by a contrivance known as the pooka. It consists of a flat board, with a little mast and sail erected on it. Its use is to carry out the extremity of a long, stout line, to which are suspended at certain intervals, a great number of droppers, each armed with a baited hook. Corks are affixed to the principal line to keep it floating, and from a weather shore, any quantity of hooks can thus be floated over the water. The corks indicate to the fisher when a fish is on a dropper, and in a small punt he attends to remove the fish and rebait the hooks. Two hundred hooks are sometimes used on one pooka, which affords much amusement and a well-filled pannier.

This beautiful Fish appears to be common in the rivers and lakes throughout Ireland; in Scotland, however, it is rare, and in the waters that dissect, as it were, the northern portion of that kingdom, it is quite unknown. On the continent, it has a much more northern range; for large Perch, of five or six pounds in weight, are abundant in the lakes and rivers of Sweden, and afford good angling. The head of a Perch is said to be preserved in the church of Luehlah, in Lapland, which measures nearly twelve inches from the point of the nose to the end of the gill-cover, which, according to the proportion of parts in ordinary specimens, would give the enormous total length of four feet for this Fish. It is possible, however, that this may be the head of some other species.

Perch resort to pits, eddies, holes, the pillars of bridges, and mill-dams; they frequent the floors of staunches early in the morning, where they may be taken in great numbers at break of day, by means of a casting-net; in these places they work to meet the fresh water that oozes through.

The Perch has a tendency to ascend towards the springs of rivers, having a great repugnance to sea-water. It delights in clean swift streams with a gravelly bottom, not very deep; it is seldom found at a greater depth than a yard below the surface. It is tenacious of life, though perhaps less so than the Carp; it has been known to survive a journey of fifty miles, in the old days of travelling, when railways were unknown.

Like other "anglers' Fish," the Perch is not very often seen on the stalls of fishmongers in London. In Billingsgate market it is, however, sometimes exposed, especially on Fridays, as it is bought chiefly by Jews to form part of their Sabbath repast. We believe that this Fish is kept by the dealers in tanks, and that those which are not sold are frequently so little injured by exposure, as to be returned to the water, where they soon recover.

O'Gorman describes the Perch as fond of noise, and as even sensible to the charms of music. One of his sons assured him that he had once seen a vast shoal of Perch appear at the surface, attracted by the sound of the bag-pipes of a Scotch regiment, that happened to be passing over a neighbouring bridge, and that they remained until the sounds died away in the distance.[2]

The Perch is a bold and fearless fish, and not a little destructive: small fry of all kinds are greedily devoured by him; he roots up the spawn-beds to feed on the deposited ova; small Roach and Trout are destroyed by him in great numbers, and even Trout of considerable size are often driven from their feeding-places near shore by this beautiful but tyrannical spinous-finned fish.

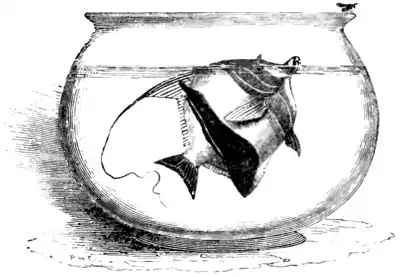

In the beautiful lake of Geneva the Perch is said to be subject to a singular accident. In the winter these fishes ordinarily remain at a considerable depth, where, from the superincumbent weight of so great a body of water, the air contained within the swim-bladder is much compressed. If now from any impulse a fish suddenly rises to the surface, the pressure being removed, the air forcibly expands, and not being able to find any outlet, the membranous bladder becomes greatly distended, sometimes to such a degree that it is forced out at the mouth of the fish, dragging the stomach, turned inside out, with it. In this sad condition, unable to sink, the poor fish floats a few days on the surface, dragging out a miserable existence, until death puts a period to its sufferings. If, however, the bladder be pierced when in this state, the contained air escapes, the viscera recover their proper position, and the fish is saved.[3]

The Perch spawns at the age of three years, when it is about six inches in length; the month of April is the season for this operation if the water be moderately shallow; but in deep water the spawning is later. In a Perch of two pounds the roe weighs seven or eight ounces, and contains, according to Harmers, 281,000 eggs, but according to Picot, nearly a million; the number varying according to the age of the fish. Large and old fishes contain more ova than the smaller ones, which is not surprising, since the individual eggs are of the same size in both; they are very minute, and have been compared to poppy seeds.[4]

The Perch, when seen alive in a clear stream, is, as we have said, a beautiful fish. Perhaps the elevation of its back may be thought to detract from its elegance of form, giving it a humped appearance. The back rises somewhat abruptly just behind the head, after which it tapers to the tail: the height of the body, independent of the fins, is about twice that of the width. The general hue of the upper parts is a rich olive, crossed by five or six dark brown bands, which become inconspicuous after death. The sides have a brassy tinge, with pearly and steel-blue reflections about the cheeks; the under parts are pure silvery white. The two dorsal fins, and the pectorals take nearly the same hues as the parts from which they respectively arise; but the caudal, the anal, and the ventrals have their rays of the most brilliant scarlet, especially the latter, and the membranes are tinged with the same hue. The iris of the eye is golden. The lateral line is distinct, running in a slightly arching line from the gill-flap to the tail-fin.

Mr. Yarrell mentions, as having been found in the waters of particular soils, specimens of the Perch almost entirely white; and others of an uniform slate-grey hue with a silvery appearance. The latter variety is obtained in the ponds of Ravenfield Park, in Yorkshire, and is found to retain its peculiarity of colour, when transferred from its native ponds to other waters.

Yet another variation of hue, associated with another curious peculiarity, is ascribed to the Perch of Malham, or Maum Tarn, in Yorkshire, by Hartley, the author of an account of some natural curiosities of that neighbourhood. Speaking of these fishes, he says, "There is certainly a very extraordinary phenomenon attending them, the cause of which I leave to naturalists to ascertain. After a certain age they become blind: a hard, thick, yellow film covers the whole surface of the eye, and renders the sight totally obscured. When this is the case, the fish generally are exceedingly black; and although, from the more extreme toughness and consistency of the membrane, it is evident that some have been much longer in this state than others, yet there appears no difference either in their flavour or condition. Perch of five pounds' weight and more have been taken. They are only to be caught with a net; and appear to feed at the "bottom, on Loach, Miller's Thumb, and testaceous mollusca."

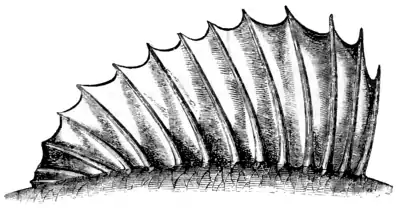

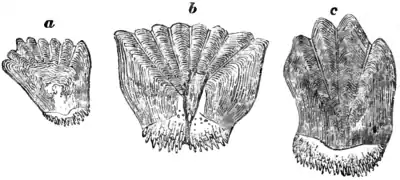

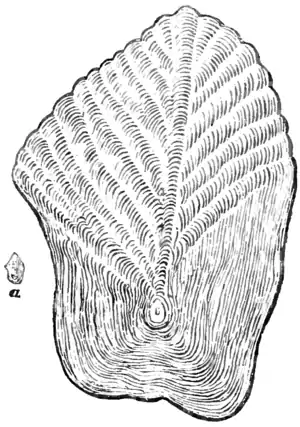

The scales of the Perch have their hinder, or free edge, set with fine crystalline points, arranged in successive rows, and overlapping. Their

front side is cut with a scolloped pattern, the extremities of undulations of the surface that radiate from a common point behind the centre. These undulations are separated by narrow furrows, across which, contrary to the ordinary rule, the close-set concentric lines that follow the sinuosities of the outline are not visible. Under the microscope they look as if they had been split in these radiating lines, after the whole number of layers had been completed, and that the fissures had then been filled with new transparent substance. The engraving above represents scales selected from different parts of the body of a Perch, and magnified. a is from the back; b is from the lateral line, and shows the tube for the passage of the lubricating mucus well developed; c is from the belly. The concentric lines, it should be observed, are much more delicate and close than could possibly be engraved without greatly enlarging the scale.

The nostril in the Perch has two external openings, surrounded by several orifices, through which issues a mucous secretion for the defence of the skin against the action of the water. "The distribution of the mucous orifices over the head," remarks Mr. Yarrell, "is one of those beautiful and advantageous provisions of Nature which are so often to be observed and admired. Whether the fish inhabits the stream or the lake, the current of the water in the one case, or progression through it in the other, carries this defensive secretion backwards, and spreads it over the whole surface of the body. In fishes with small scales, this defensive secretion is in proportion more abundant; and in those species which have the body elongated, as the Eels, the mucous orifices may be observed along the whole length of the lateral line."[5]

Family II. Sphyrænadæ.

(Sea-Pikes).

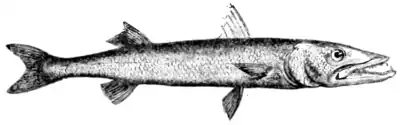

The fishes of this Family were placed by Linnæus among the Pikes, which they resemble in their lengthened form, in their strong and pointed teeth, and in the projection of their lower jaw. They are now, however, widely removed from that genus. Cuvier arranged them in the great Family of the Perches, with which they have many points in common; but the Prince of Canino forms them into a distinct Family.

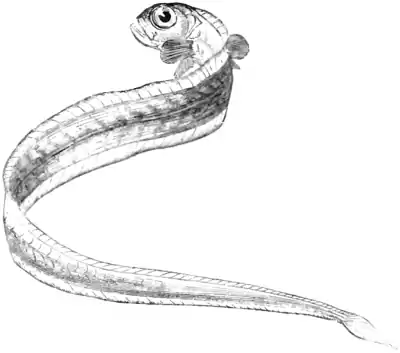

They have the ventral fins placed considerably behind the pectorals, and the bones of the pelvis are quite detached from the bones of the shoulders. The head is long, and the lower jaw projects beyond the upper, giving a ferocious aspect to the countenance, well borne out by the habits and powers of at least the principal genus. They have two dorsals, both placed far behind; the second is small, and in one of the genera

(Paralepis), fleshy. The Family is very limited, containing only about fifteen living species, inhabiting the Mediterranean and the warmer parts of the ocean. There are, however, thirteen fossil species assigned to it.

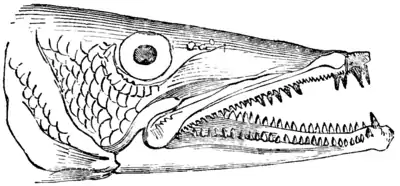

Genus Sphyræna.

The technical characters of this genus are, that the body is slender and much lengthened; the jaws are long and broad, but of little depth; the mouth is large, armed with strong teeth, some of which are larger and stouter than the others; the chin is advanced and pointed; the two dorsal fins are triangular in form, remote from each other, and dividing the whole length of the body into three equal parts; the ventrals are placed beneath the first dorsal.

The Barracoota of the West Indies (Sphyræna barracuda, Cuv.), is reckoned among the number of marine monsters greedy of human flesh. It is common in the seas that wash those lovely tropical islands, where it attains the length of ten or twelve feet, though it is more generally met with about half that size. The thickness is not in

proportion to the length. The mouth is wide, the lower jaw projects beyond the upper, and is armed with formidable teeth, with two larger pointed canines in front; the upper jaw has many large and strong teeth scattered among minute ones. The two dorsals are placed far apart, the first immediately above the ventrals, the second above the anal. The formula of the fin-rays is as follows: D. 5; 1—9; C. 19; P. 12; V. 1—5; A. 1—9. The tail is much forked. The upper parts are dark greyish brown, becoming paler on the sides, the belly white. It is covered with small thin scales.

This formidable and voracious fish is much dreaded in the seas which it inhabits. It not unfrequently attacks and devours men while bathing; Dutertre affirms that it is even more dangerous than the dreadful shark, inasmuch as noise and motion, so far from intimidating it, only excite it the rather to rush towards its victims. Notwithstanding this anthropophagous appetite, however, it is eaten with relish, and is publicly sold in the fish-markets. A graver objection to it is that it is occasionally poisonous, which the colonists believe is owing to its feeding on submerged "copper-banks," or else to its having eaten the deadly fruit of the Manchioneel-tree. If incautiously tasted under such circumstances, it is said to produce sickness, vomiting, and intolerable pain in the head, accompanied with loss of the hair and nails; and, in very bad cases, immediate death is the result. As a criterion of its wholesomeness, the teeth and liver are examined; if the former be white and the latter bitter, it is sound; but if the teeth be green and the liver sweetish, it cannot be eaten with impunity.

"What has been reported," observes M. Cuvier, "of the poisonous fishes of hot countries, and of that disease called siguatera, which they occasion in certain circumstances, is so curious and interesting, that I am justified in inserting the information collected by M. Plée on the Barracoota, which I have found in the papers of that unfortunate naturalist. Many persons, says he, fear to eat this fish because they have had frequent evidence of its causing disease, and sometimes death. This poisonous quality of the Barracoota belongs very certainly to a particular state of the individual, which appears to occur at different seasons of the year.

"I have consulted many persons with regard to the poison of the Barracoota; all have assured me that there is an infallible mode of determining whether it is, or is not, poisonous. For this end they have only to observe if, in cutting it up, there flows away a sort of white water, or rather a kind of thin matter, which is, in every case, a certain sign that the fish is in the diseased state of which I have spoken above. D. Arthur O'Neill, Marquis del Norte, has told me that he has seen experiments tried on dogs, and that all have confirmed the exactness of this criterion. The symptoms of poisoning by the Barracoota are, a general trembling, nausea, vomiting, and acute pains, particularly in the joints of the arms and the hands. Sometimes the symptoms succeed each other with such rapidity that it becomes extremely difficult to determine with precision the different periods of the disease.

"When death does not terminate the malady, which happily is the more ordinary case, the virus is sometimes seen to cause pathological phenomena altogether singular. The pains in the joints become stronger; the nails of the feet and hands gradually fall away; the hair also, which is of a nature analogous to the nails, ends by falling off. These phenomena have been observed in many individuals, sometimes continuing during a great number of years. A person has been mentioned to me, who suffered in this way more than twenty-five years.

"It is a remarkable fact that when the Barracoota has been salted, it never causes any accident. At St. Croix, for example, they are in the habit of eating it only the day after it has been salted. Does salt act as an antidote to the poison of this fish?

"I have not myself been a witness of any cases of poisoning by the Barracoota, and I have only recorded what I have been told by persons in other respects well instructed and worthy of credit."[6]

Family III. Mullidæ.

(Surmullets).

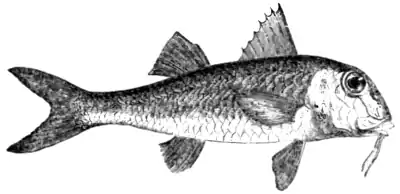

This also is a Family of limited extent, arranged by Cuvier with the Perches. Its distinctive characters are these:—the shape is somewhat oval, but the fore parts are thick in proportion to the hind; the head is large, somewhat compressed, higher than broad; the profile is abrupt, approaching to a vertical line; the eyes are placed near the summit, but look laterally; the mouth is small, armed with minute teeth; the lower jaw is furnished with two fleshy beards (cirri), which depend from its under side; the line of the back is arched, that of the belly nearly straight; the gill-cover and body are clothed with large scales, easily detached: there are two dorsal fins, widely separated; the caudal is forked.

About fifty species are included in this Family, contained in two genera, Mullus and Upeneus. The former of these, containing but two species, is found in the Mediterranean and in the British seas; the latter and more numerous one, little differing from it in appearance or structure, is distributed over the tropical parts of the ocean. They are nearly all coloured with different shades of red, often varied with yellow or pale stripes; their flesh is much esteemed.

Genus Mullus. (Linn.)

The European Surmullets are distinguished by having the characters already enumerated more strongly developed; the head is very abrupt, the profile nearly vertical, the gill-cover is smooth, and destitute of any spine; the teeth on the palate and in the lower jaw very minute.

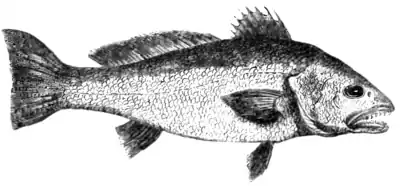

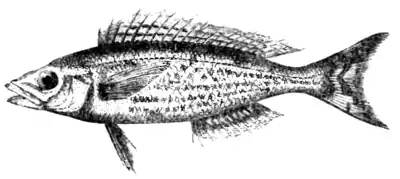

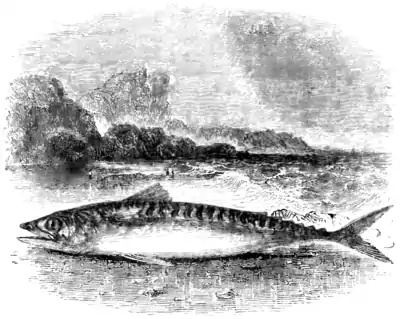

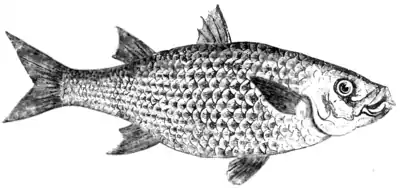

Of the two species which form this genus, both of which are marked in catalogues as British, one is as common as the other is rare. The former is

the Striped Surmullet (Mullus surmuletus, Linn.), and is found in our fish-markets throughout the year, though in greatest abundance during the summer months. It is commonly about ten inches or a foot in length, and is rarely known to exceed fourteen inches. Its form and general appearance will be recognised from the accompanying engraving, but it should be seen alive, or at least just dead, to convey a notion of its beauty, which depends on its evanescent hues. The ground-colour is a delicate pink, interrupted by three or four pale yellowish bands which run down the sides. The scales, however, which are very large, are removed with a slight degree of force; and wherever this occurs, there is a deposit of blood at the injured part below the outer skin; manifested by the colour becoming then of a purplish red, and hence we so commonly see this fish, especially after it has been handled, marbled with patches of purple and scarlet upon the delicate rose-colour of the ground.

The Surmullet is much esteemed for the table; the flesh is of agreeable flavour, and easy of digestion. It is customary to prepare it for cooking without drawing, like the Woodcock; the reason in both cases being that the food consists of soft molluscous or annellidous animals, of which little traces remain in the intestines. The Romans carried their admiration of this fish to a most extravagant pitch in the luxurious times of the Empire. The satirical poets, lashing the vices and follies of the age, have given us some particulars of this mania, only surpassed by the Tulip-madness which raged in Holland in the 17th century, when a sum equal to 425l. sterling, together with a carriage, horses, and harness, was given for a single bulb. One Calliodorus gave a sum of money equal to ten guineas for a Surmullet of four pounds' weight; one of six pounds was bought for 48l.; one still larger for 64l.; and three of equal size were purchased by the Emperor for the same entertainment at the enormous price of 243l. 10s. At length Tiberius attempted to restrain the extravagance by imposing a tax upon all provisions brought to market.

Messengers were sent at great expense to the most distant shores of the Mediterranean to procure these fishes, which, when brought home, were kept alive in vivaria or tanks of sea-water. By a refinement of luxury, the Mullets were even brought to table alive, that the guests might feast their eyes upon the changes of hue which flit over the bodies of these fishes in the agonies of death. "The fishes," says Cicero, "swim under the couches of the guests. A Mullet is not considered fresh unless it actually die before their eyes; they gaze upon it exposed to view in glass bowls, and watch the various tints that play over it one after another as it passes from life to death." The species selected for this inhuman exhibition appears to have been the smaller and more rare M. barbatus, which is destitute of yellow stripes, and does not exceed six inches in length. The name of the genus Mullus is said to have been given to these fishes from their hue resembling that of the Mulleus or scarlet sandal worn by the Roman Consuls and Emperors.

The curious organs called beards (cirri) that are attached to the chin in these and some other fishes are connected with the search after food. Mr. Yarrell has some interesting observations on this subject, which we shall here quote from his valuable volume on British Fishes. "These cirri are generally placed near the mouth, and they are mostly found in those fishes that are known to feed very near the bottom. On dissecting these appendages in the Mullet, the common Cod, and others, I found them to consist of an elongated and slender flexible cartilage, invested by numerous longitudinal muscular and nervous fibres, and covered by an extension of the common skin. The muscular apparatus is most apparent in the Mullet, the nervous portion most conspicuous in the Cod. These appendages are to them, I have no doubt, delicate organs of touch, by which all the species provided with them are enabled to ascertain, to a certain extent, the qualities of the various substances with which they are brought in contact; and are analogous in function to the beak, with its distribution of nerves, among certain wading and swimming birds, which probe for food beyond their sight; and may be considered another instance, among the many beautiful provisions of Nature, by which, in the case of fishes feeding at great depths, where light is deficient, compensation is made for consequent imperfect vision."[7]

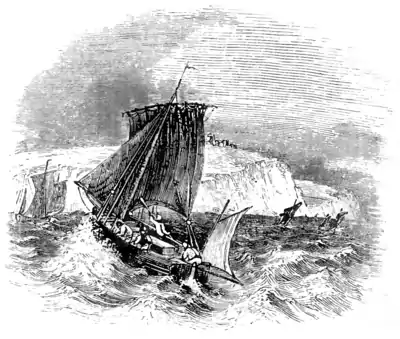

The Striped Surmullet is occasionally taken in great abundance: the eminent zoologist just cited mentions five thousand taken in one night in Weymouth Bay, in August, 1819; and ten thousand sent from Yarmouth to the London market in one week, in May 1831. Their presence, however, is precarious; sometimes they become quite rare, where a day or two before they were abundant; other spots at the same time becoming the favoured scenes of their resort. They are principally taken with the trawl-net, which drags along the bottom of the sea.

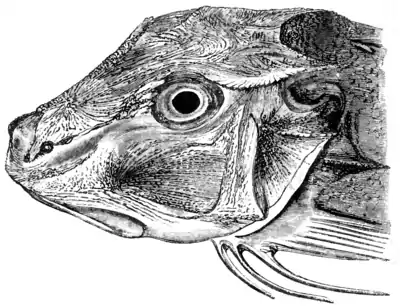

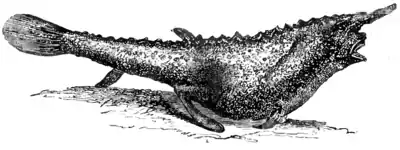

Family IV. Trigladæ.

(Gurnards.)

Cuvier formed these Fishes into the second Family of the Acanthopterygii in his system, giving to the group, however, thus constituted, no other appellation than the descriptive one of "Fishes with hard cheeks." In these words their most obvious character is indicated, the head and face being encased in a solid buckler of bone, or in hard plates soldered together. In general, the plates as well as the gill-covers, are more or less armed with projecting spines. The technical distinction between the Gurnards and the Perches, to which Family they are very closely allied, consists in the bone beneath the eyes (the sub-orbital bone)—which is greatly dilated, so as to cover the cheeks,—being jointed to the gill-cover. Those curious fishes of the Perch family, the Stargazers (Uranoscopus), have the head mailed and angled much in the same way as the Gurnards, and have their eyes directed even still more vertically; but, in that genus, the sub-orbital bone, though very broad, is united with the temporal bones, and not with the gill-cover.

The fins are well developed; especially the pectorals, which often assume gay colours, and dimensions so great, that, like the true Flying fishes of another Order (Exocœtus), these fishes are capable of projecting their bodies into the air, and of taking long leaps. Some genera have several finger-like rays, unconnected by membrane, in front of the pectorals; which probably serve them as organs of touch, endowed with a sensibility to impressions that are indispensable in the situations where they haunt, as bottom feeders.

About two hundred and sixty species are enumerated in the Family, of which just one tenth part are European.

To this Family belongs a genus of fishes containing many well-known inhabitants of our coasts and rivers, the Sticklebacks (Gasterosteus). We have seven species, all of them of small size, some of which are familiar to every truant schoolboy by their abundance, their pigmy dimensions, their armature of spines and plates, their vivacity and boldness, and the beautiful tints of green, crimson, and silver, with which they are frequently adorned.

These little fishes, however, present other claims to our attention; for they afford additional examples of an instinct which has been considered almost if not quite unknown in the Class to which they belong, that of nest-building. The habits of one of these species, which appears to be the commonest of the Three-spined Sticklebacks (G. trachurus) have been described by a careful observer in a little-known periodical, called "The Youth's Instructor;" and his account carries its own guarantee of correctness with it. "In a large dock for shipping on the Thames," observes this writer, "thousands of these fish were bred some years ago; and I have often amused myself for hours by observing them. While multitudes have been enjoying themselves near the shore in the warm sunshine, others have been busily engaged in making their nests, if a nest it may be called. It consisted of the very minutest pieces of straw, or sticks, the exact colour of the ground at the bottom of the water, on which it was laid: so that it was next to an impossibility for any one to discover the nest, unless he saw the fish at work, or observed the eggs. The nest is somewhat larger than a shilling, and has a top or cover, with a hole in the centre, about the size of a very small nut; in which are deposited the eggs, or spawn. This opening is frequently concealed by drawing small fragments over it; but this is not always the case. Many times have I taken up the nest, and thrown the eggs to the multitude around, which they instantly devoured with the greatest voracity. These eggs are about the size of poppy-seeds, and of a bright-yellow-colour; but I have at times seen them almost black, which I suppose is an indication that they are approaching to life. In making the nest, I observed that the fish used an uncommon degree of force when conveying the material to its destination. When the fish was about an inch from the nest, it suddenly darted at the spot, and left the tiny fragment in its place; after which it would be engaged for half a minute in adjusting it. The nest, when taken up, did not separate, but hung together, like a piece of wool.… The place chosen by these fishes for their nests is where the ground forms an inclined plane, and in about six inches of water.… I think they breed early in the month of August."

Another species of the same genus, the largest which is found on our shores, the Fifteen-spined Stickleback (G. spinachia), sometimes called the Sea-adder, is endowed with a similar instinct. The author of a communication to the Royal Institution of Cornwall, republished in the "Zoologist," thus records his observations:—"During the summers of 1842, and 1843, while searching for the naked mollusks of the county, I occasionally discovered portions of sea-weed and the common coralline hanging from the rocks in pear-shaped masses, variously intermingled with each other. On one occasion, having observed that the mass was very curiously bound together by a slender silken-looking thread, it was torn open, and the centre was found to be occupied by a mass of transparent amber-coloured ova, each being about the tenth of an inch in diameter. Though examined on the spot with a lens, nothing could be discovered to indicate their character. They were, however, kept in a basin, and daily supplied with sea-water, and eventually proved to be the young of some fish. The nest varies a great deal in size, but rarely exceeds six inches in length, or four inches in breadth. It is pear-shaped, and composed of sea-weed or the common coralline, as they hang suspended from the rock. They are brought together, without being detached from their places of growth, by a delicate, opaque, white thread. This thread is highly elastic, and very much resembles silk, both in appearance and texture; this is brought round the plants, and tightly binds them together, plant after plant, till the ova, which are deposited early, are completely hidden from view. This silk-like thread is passed in all directions through and around the mass, in a very complicated manner. At first, the thread is semi-fluid, but by exposure it solidifies; and hence contracts and binds the substances forming the nest so closely together, that it is able to withstand the violence of the sea, and may be thrown carelessly about without derangement. In the centre are deposited the ova, very similar to the masses of frog-spawn in ditches.…

"It is not necessary to enter into minute particulars of the development of the young, any further than to add that they were the subject of observation till they became excluded from the egg, and that they belonged to the Fifteen-spined Stickleback (Gasterosteus spinachia). Some of these nests are formed in pools, and are, consequently, always in water: others are frequently to be found between tide-marks, in situations where they hang dry for several hours in the day; but whether in the water or liable to hang dry, they are always carefully watched by the adult animal: on one occasion, I repeatedly visited one every day for three weeks, and invariably found it guarded. The old fish would examine it on all sides, and then retire for a short time, but soon returned to renew the examination. On several occasions I laid the eggs bare, by removing a portion of the nest; but when this was discovered, great exertions were instantly made to re-cover them. By the mouth of the fish the edges of the opening were again drawn together, and other portions torn from their attachments and brought over the orifice, till the ova were again hid from view: and as great force was sometimes necessary to effect this, the fish would thrust its snout into the nest as far as the eyes, and then jerk backwards till the object was effected. While thus engaged it would suffer itself to be taken in the hand, but repelled any attack made on the nest, and quitted not its post so long as I remained; and to those nests that were left dry between tide marks, the guardian fish always returned with the returning tide, nor did they quit the post to any great distance till again carried away by the receding tide."

It is right to observe that Mr. Couch, who in his "Illustrations of Instinct," quotes both of the above papers, suspects that the nest, in the latter case, was that of the Shanny (Blennius pholis), and that the Sticklebacks watched it with a very different motive from parental affection. We do not, however, concur in this gentleman's conclusions.

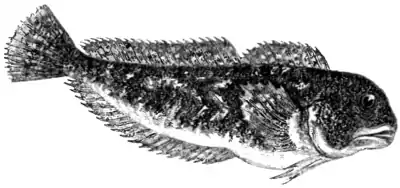

Genus Trigla. (Linn.)

The Gurnards have the head somewhat four-sided, more or less resembling the half of a pyramid divided vertically; hence the profile resembles that of the Surmullets. It is, as has been intimated, defended by long shields, those of the gill-cover and shoulder terminating in a spine or lancet. The body is lengthened, rounded above, with the belly flattened, tapering from the head backwards; clothed with small prickly scales, firmly embedded in the skin, very compactly arranged, and often accompanied by rows of spines placed along the lateral line. There are two dorsal fins, the first short but high, with spinous rays; the second long, with rays flexible at the tips. The pectorals are large, with strong rays, and with the membrane often coloured; there are three free rays before the base of each, covered with a fleshy skin, well supplied with nerves. The ventrals are also large, and situated immediately beneath the pectorals. The anal corresponds with the second dorsal. The caudal is slightly lunate, or hollowed at the extremity. Both of the jaws, and the front of the vomer, are furnished with minute, close-set teeth. The gill-opening is large, and the branchiostegous rays are seven.

The swimming-bladder in this genus is rather large, and presents considerable diversity of form. In general it is somewhat heart-shaped, more or less cleft in front, but in the Sapphirine Gurnard, presently to be described, it is triple, the principal sac giving off, on each side, an accessory sac, tapering off to a point behind, but united to, and opening into, the main chamber at the front part. The membranes of which this organ are composed are thick, dense, and leathery.

Notwithstanding this development of the air-vesicle, the Gurnards are ground-fishes. They chiefly haunt the vicinity of the bottom, where they feed on crabs, lobsters, and other crustacea; not, however, confining themselves to these, for they are very voracious.

The Grey Gurnard (Trigla gurnardus, Linn.) seems to affect the surface more than the other species of the genus. On the Atlantic shores of Scotland and Ireland it is not uncommon to see immense shoals of this Crooner, (as it is called on the former coast,) rippling the smooth water as they cut the surface, so as to be readily shot with a fowling piece.

The principal mode of taking Gurnards is by means of the trawl-net, a long conical net already described, dragged along the bottom after a boat under sail. But the Grey Gurnard is taken on the coast of Ireland, by the fleet-line, like the Mackerel. A writer in the "New Sporting Magazine," who well describes him as "all points and angles," his "huge horny bony head, armed at all points with barbs and thorns," his "tremendous dorsal fin, a natural chevaux de frise, for the hand of the incautious fisherman;" and, as to his habits, as "living perpetually on the surface, and being prodigiously gregarious and voracious beyond all example," says, "I have sailed through them in shoals to which the eye could see no limit, rolling lazily on the water, with the points of the fin projecting over the surface, and swallowing everything which came within view. In the summer months their sole food is the herring-fry; and I have often found them gorged with the miserable little fish to an extent which their size would seem to render absolutely impossible."

"In unhooking the Mackerel there is no difficulty. It is not so, however, with his friend and companion the Gurnard. He is a far more dangerous customer, even, than the Perch, the terror of the inexperienced river angler. The moment your hand touches him,—whisk! up fly the back fin, the thorns of the head, and the whole array of points and barbs with which he so liberally provides you; and it may be that your lacerated fingers will remind you for several days of the necessity for caution in every future attempt. The ordinary method of avoiding this inconvenience,—more serious than might perhaps be imagined, has somewhat of cruelty about it. It is to stun the fish by a hard knock against the deck or gunwale of the boat. The fins and thorns are thus erected before the fisher places his hand upon the fish; he sees the danger, and is enabled to keep clear of it. But the end may be attained as securely without recourse to this cruel expedient. Any one who has ever taken a Pike off the hook, will at once perceive the plan. Let the Gurnard be seized with the fingers between the eyes, just as the Pike, and the hand will be secured against all danger."[8]

The word Gurnard is supposed to be derived from the French gronder, to grumble; and to indicate the power, rare among fishes, but possessed by all the species of this genus, of emitting vocal sounds. The common Red Gurnard is termed the Cuckoo, from its uttering a double note like that of our well known woodland bird; another species is named the Piper; and the grey species just alluded to, derives its appellation of Crooner from the provincial word Croon, which signifies a hollow humming sound. The voice is generally heard the instant the fish is taken into the hand, or removed from the water, but the last named species is said to utter its "crooning" as it ploughs the surface with its cleft and prickly muzzle.

Like other bottom fishes, the Gurnards live a long time out of the water.

One of the most common as well as the largest of our species is the Sapphirine Gurnard (Trigla hirundo, Linn.), which owes both its common and its scientific appellation to its large pectorals, which resemble wings; and are on their inner or posterior surface of a fine deep blue colour, becoming scarlet near the last ray. All the other fins are tinged with scarlet, more or less distinctly; the caudal and the first dorsal brilliantly. The two dorsals are set in a groove, bounded by two rows of strong and sharp points pointing backwards; this furrow does not extend

beyond the range of the two fins either in front or behind. The bony armour which encases the head, carries several spines; the front part of the orbit of each eye is armed with three small ones; the crown plate ends in a strong broad one on each side; the gill-cover, and the fore-gill-cover each carry one, and there is another stout and strong one pointing backwards, affixed to the bone of the shoulder. Besides which, the whole surface of the head is roughened, like a rasp, with minute knobs running in various fantastic lines and curves.

The ground colour of the upper parts is a dull olive; that of the under parts silvery white, the whole tinged with pale red; this latter hue is also distributed about in irregular mottlings, especially along the sides, on the mouth and chin, and on the finger-like pectoral rays. The eyes are large, and golden-yellow. This species attains the length of two feet or more.

The scales are very minute, more or less

a, Natural size.

angular in their outline, free from prickles: the concentric lines (striæ) are fine, close-set and numerous, and are interrupted by lines of clear glassy substance, branching from a central one like the veins of a leaf; these lines correspond with indentations in the outline.

When alive in the water, the Gurnards are described as being very beautiful; the gay hues with which they are generally adorned possessing a glittering brilliancy heightened by the transparency of the element through which they are seen; more particularly in the rays of the sun, when every motion and every turn brings out some new play of colour or flash of radiance.

Family V. Sciænadæ.

(Maigres.)

The Maigres are an extensive Family, including, according to the Prince of Canino's estimate in 1831, two hundred and thirty one species; but now considered by the same Zoologist to contain but one hundred and sixty five. Of this large number, four only are found in the European seas, and two are British. The tropical parts of the Atlantic, including the West Indian Seas, are the great home of the Family; some are found in the Indian Ocean, but scarcely a single species in the Pacific.

In many respects the Maigres resemble the Perches; the operculum is armed with spines, and the pre-operculum is cut into notches like the teeth of a saw: they have strong teeth, but none in either the vomer or the palate, where the Perches are furnished with them; the muzzle is thickened and obtuse; the mouth comparatively small; the back much arched; the tail and caudal fin are frequently inclined upwards in a slight degree: and finally, there are in general a few scales on the basal part of the dorsal or dorsals, of which fins, as in the Percadæ, some genera have one much lengthened but continuous, others indented by a depression more or less deep, and others completely divided into two.

Some of the Maigres attain a great size, and some are adorned with rich colours and brilliant metallic reflections; but elegance of form is not, in general, one of their characteristics. Their flesh is highly esteemed for the table.

Genus Sciæna. (Linn.)

The head in this genus is large, and as it were inflated, supported by cavernous bones: there are two separated dorsal fins; the spines of the anal are weak and slender, and that fin is short; the operculum terminates in one or more spines, and the pre-operculum is serrated; but the notches are apt to be effaced by age. There is a single row of strong teeth in each jaw, and a narrow line of small ones in the upper; but none on the vomer or palate: there are seven gill-rays. The whole head is clothed with scales; the two strong bones of the ears are larger than in most other fishes; the chin is not furnished with cirri or beards; the air-bladder is often curiously fringed. The species inhabit the Mediterranean, Atlantic, and Indian seas.

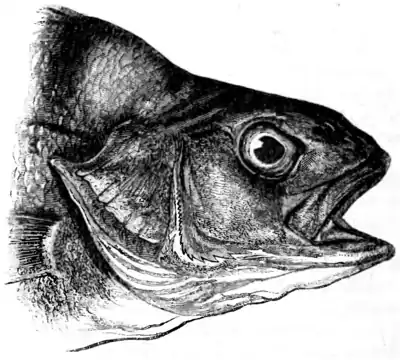

The waters that lave our own coasts occasionally produce specimens of a noble Sciæna which attains a length of six feet, and a bulk proportionate. It is the Maigre of the French (Sciæna aquila, Cuv. et Val.), but our fishermen call it the Stone Basse, and confound it with another fish of large size, which resembles it, one of the Percadæ.

Mr. Yarrell describes the colour of this rare fish when quite fresh, as a uniform greyish silver, slightly inclining to brown on the back, and lightest on the belly; but the whole body assuming a much darker tint, after it has been kept for a few days. The fins are reddish brown; the first dorsal, the pectorals, and the ventrals, brighter in hue than the others. The second dorsal is twice as long as the first; the caudal is, as it were, cut off with a straight vertical edge.

Many of the Sciænadæ have a similar power to that already mentioned as characterizing the Trigladæ, that of producing vocal sounds. The Maigre’s voice is compared to the purring of a cat, and it utters it not only in the air when removed from the water, but even when swimming considerably beneath the surface. When swimming in shoals, it is said the purring of the Maigre is audible from a depth of twenty fathoms.

The flesh of such specimens as have from time to time found their way to our markets has been considered good, though rather dry. In the Mediterranean, however, it has been very highly esteemed, from the earliest times, and bears the title of King's fish, from its reputed excellence. "It appears always to have been in great request with epicures; and as, on account of its large size, it was always sold in pieces, the fishermen of Rome were in the habit of presenting the head, which was considered the finest part, as a sort of tribute, to the three local magistrates who acted for the time as conservators of the city."

A curious story is told of the travels and adventures of a Maigre's head that was presented to the magistrates in the pontificate of Sextus X. The conservators offered it as an acceptable present to the Pope's nephew ; by whom it was sent to one of the Cardinals; the latter sent it as a propitiatory offering to a banker to whom he was deeply in debt; and the banker presented it to his mistress. The interest of the story rests chiefly on the ingenuity of a dinner-hunter, who contrives to trace the savoury dish through all its migrations, and succeeds at length in obtaining an invitation to partake of the dainty.

The two hard bones that are lodged in the sides of the head, commonly known as the ear-stones, have been supposed by the vulgar, and by the scientific in former times, to possess medicinal powers. They were called colic-stones; and their virtues as curative of this disorder were supposed to be exercised by being worn round the neck, usually mounted in gold. But then it was indispensable that they should have been received as a gift; the fact of payment having been made for them, would, it was pretended, deprive them of all their value. It is to be regretted that superstitions, equally groundless with this, are still common in this enlightened age, and in our own country; diseases being considered removable by the wearing of certain amulets or charms.

The Maigre, as a British fish, is a great rarity; the Mediterranean, especially its northern shore, is its chief resort. In its habits it is somewhat migratory; swimming in small shoals, which shift their quarters from one part of the coast to another, seldom remaining long in a place. The air-bladder is long, and tapers to a point behind; the free edge of the membrane, being cut into irregular fringes all along each side, gives it a singular appearance.

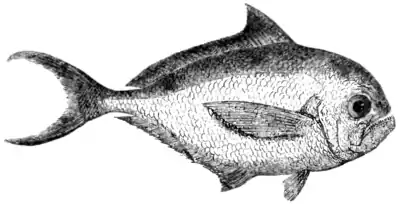

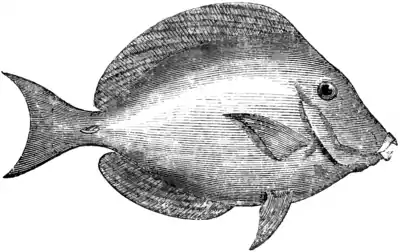

Family VI. Sparidæ.

(Sea-breams.)

In form these fishes somewhat resemble those of the preceding Family, presenting a high, rather oval, vertical outline, of greater depth than thickness. They have but one dorsal, which is never clothed with scales in any degree: the operculum is not spinous, nor is the pre-operculum notched: the muzzle is not thickened, nor are the bones of the skull cavernous; the mouth is not protrusile. In addition to these negative distinctions, it may be added that the jaws are furnished with round fiat grinding teeth, arranged like the stones of a pavement, and often with strong pointed canines in front; the pectoral fins are always pointed, and the caudal forked; characters which indicate the power of swift progression through the water.

The colours of the Marine Breams are generally elegant without being showy; silvery grey or pearly white, varied occasionally with gilded or brassy reflections, and flushed with iridescent hues of rose-red, pale blue, green, and yellow, may be considered as characteristic of the Family. The fins, however, are destitute of colour, or are tinged only with dusky-brown.

From the structure of their teeth, it might be inferred that these fishes were predatory, and that their food often presented itself in a form which required great crushing and grinding force. And this is indeed the case, crustacea and mollusca, but especially the latter, affording them the main part of their sustenance; both of these classes comprising animals encased in crusts or shells, often of stone-like hardness. The common Gilt-head (Chrysophrys aurata, Cuv.), for example, is able to crush and grind to powder, with its powerful millstone-like teeth, the thick stony shells of the genera Turbo, Buccinum, and Trochus, the Periwinkles, Whelks, and Tops, of our rocky shores.

The Family is extensive, comprising, according to the latest estimate, two hundred and forty species, of which number nearly one-tenth belong to the European coasts; the rest are distributed over the shores of both hemispheres, their prevalence increasing as we approach the tropics.

In the larger Families of animals it is desirable to have subdivisions of a rank higher than that of genera; and there are always found on examination variations of structure, each possessed by a certain number of genera in common, by the selection of which such sub-division may be effected. In treating of the Percadæ, we briefly enumerated the subordinate groups into which that immense Family is divided; we will now indicate those into which Cuvier has distributed the Sparidæ.

1. The Sparina have the jaws set with round flat teeth like paving-stones. Eighty species belong to this group, of which sixteen are European, and five are British.

2. The Denticina have all the teeth conical and pointed, and the front ones hooked. This is the most important division, as regards number, though not the most typical; as it includes one hundred and twenty species, mostly tropical. Four only of these are European, of which one is marked as British, the Four-toothed Sparus, or Toothed Gilthead (Dentex vulgaris, Cuv.) It must, however, be reckoned among the very rarest of native animals, its claim to be so regarded resting on the authority of a single specimen. It fortunately happened that this rarity fell into the hands of Mr. Donovan, from whose "History of British Fishes," we extract the following interesting note of its powers, habits, and uses.

"A more voracious fish is scarcely known; and when we consider its ferocious inclination, and the strength of its formidable canine teeth, we must be fully sensible of the great ability it possesses in attacking other fishes, even of superior size, with advantage. It is asserted, that when taken in the fishermen's nets, it will seize upon the other fishes taken with it, and mangle them dreadfully. Being a swift swimmer, it finds abundant prey, and soon attains to a considerable size. Willoughby observes, that small fishes of this species are rarely taken; and the same circumstance has been mentioned by later writers. During the winter it prefers deep waters; but in the spring, or about May, it quits this retreat, and approaches the entrance of great rivers, where it deposits its spawn between the crevices of stones and rocks.

"The fisheries for this kind of Sparus are carried on upon an extensive scale in the warmer parts of Europe. In the estuaries of Dalmatia and the Levant, the capture of this fish is an object of material consideration, both to the inhabitants generally as a wholesome and palatable food when fresh, and to the mercantile interest of those countries as an article of commerce. They prepare the fish, according to ancient custom, by cutting it in pieces, and packing it in barrels with vinegar and spices, in which state it will keep perfectly well for twelve months."

3. The Cantharina contain but a single genus, in which the teeth are numerous, minute, and conical, placed in several rows; those of the outer row larger and more curved than the others. Of this limited group, England possesses one species, the Black Sea-bream (Cantharus lineatus, Mont.), which is by no means uncommon.

4. The Obladina have the foremost range of teeth compressed, placed close together, and armed with a cutting edge, which is more or less notched. This group contains only fifteen species, several of which, found in the Mediterranean, are distinguished by the metallic lustre of their appearance, their sides presenting the likeness of silver and burnished steel, in which are imbedded longitudinal parallel bands of gold.

Genus Pagellus. (Cuv.)

The present Genus belongs to the first of the sub-families, mentioned above. It is characterized by the teeth in the front half of the jaws being numerous, close-set, slender, and pointed; those in the rear being rounded molars, disposed in two or three rows, those of the outer row the most powerful. There is but a single dorsal fin, which is lengthened, and composed of both spinous and flexible rays; the pectorals are pointed; the cheeks and gill-covers are covered with scales; the form is deeper than thick; the outline of both the belly and the back is rounded.

The species of the genus Pagellus are common in the Mediterranean, and on the shores of the Atlantic, as far north as Denmark, beyond which they appear to be unknown. Three are found on our own coasts, two of which are rare and accidental visitants, and one is a common fish.

The Common Sea-Bream (Pagellus centrodontus, Cuv.) is about a foot and a half long, six inches deep, and two and a half inches thick; its form is much compressed, its outline both above and below gracefully swelling. The eye is enormous, and this gives it a peculiar appearance; the wide iris is golden or silvery. The hue of the upper parts is reddish-grey, the sides and belly pearly, with faint blue stripes running longitudinally. The dorsal and anal fins are strong and spinous, and are lodged in a singular groove; they are brownish; the pectorals, ventrals, and caudal are pale red. There is a blackish spot at the commencement of the lateral line. The sides of

the head gleam in parts like frosted silver, or like the back of a looking-glass newly silvered.

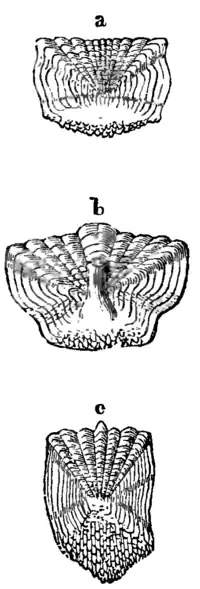

The scales (see the engraving on the following page) generally approach, more or less nearly, to a square form, slightly bulging at the sides; the front, or attached end, scalloped at the edge, and waved in a radiating manner: the hinder, or free end, marked with a number of minute flexible points lying one over the other, most numerous on the scales of the belly. Those of the lateral line have the mucus-tube short but wide. a, represents a scale from the back; b, one from the lateral line; c, one from the belly. The silvery pigment beneath the scales does not come off with the latter when these are detached, but remains adhering to the skin, and is with difficulty separated.

SCALES OF SEA-BREAM.

We can add our testimony to that of Mr. Yarrell, with respect to the excellency of this fish, when cooked as he prescribes.

The Sea-bream, or Gilt-head, as it is likewise called, is taken all around the shores of England, but is much more common in the British Channel than either on the east or west coast, and to the Scottish fishermen it is scarcely known. In the London market it is by no means uncommon, in the summer and autumn months. During the prevalence of frosty weather it retreats into deep water, where, as Mr. Yarrell informs us, on the authority of Mr. Couch, it deposits its spawn at the commencement of winter. The young fry, which go by the name of Chads, are about an inch in length in January; by the middle of summer they are five or six inches long, and attain half their full size, or about nine inches, by the end of their first year. The fry of half a year old congregate in immense numbers around the shores in summer, and are caught by anglers with the utmost ease in harbours and from the rocks, since they bite eagerly at any bait. Their food, both in the young and the adult state, comprises both animal and vegetable substances: Mr. Couch says, "They devour the green species of sea-weeds, which they bite from the rocks, and for bruising which their teeth are well suited, as are their long and capacious intestines for digesting it." The great strength of their jaws and teeth, however, bespeaks heavier labour assigned to these organs than that of bruising sea-weeds. Colonel Montagu found in the stomach of one, besides some small Sand-launce, the limbs of crabs, and fragments of shells. And in the stomach of one which we lately examined, there were found numbers of bivalve shells, all of one kind, a small grey Tellina, some of which were perfect, but most were broken, crushed, and ground down to a coarse powder by the action of the strong molars.

"In its general habits," says the excellent naturalist, to whom we owe so much of our knowledge of the fishes of the west of England, "the Sea-Bream might be considered a solitary fish; as when they most abound, the assemblage is formed commonly for no other purpose than the pursuit of food. Yet there are exceptions to this; and fishermen inform me of instances in which multitudes are seen congregated at the surface, moving slowly along as if engaged in some important expedition. This happens most frequently over rocky ground in deep water."[9]

Family VII. Mænadæ.

(Mendoles.)

With much in their form and characters that resemble the preceding Family of the Sparidæ, the Mænadæ differ from them in the extreme extensibility, and retractibility of the upper jaw, a peculiarity dependent on the length of the intermaxillary pedicels, which withdraw between the orbits of the eyes. They have teeth in the jaws, which are very fine and close set, resembling the pile of velvet; in general, the palate is toothless. The body is furnished with scales, some of which, very small and delicate, often, but not always, extend upon the dorsal fin; the ventrals are placed beneath the pectorals. Their air-bladder is large, simple, and rounded in front; commonly divided posteriorly into two long horns, which penetrate into the muscles of the tail, on each side of the internal spines of the anal fin.

The four genera which compose this Family, comprising, according to the Prince of Canino, sixty-one species, are thus distributed. Mæna is confined to the Mediterranean; Smaris inhabits the same sea, but less exclusively, a few species being found in the East and in the West Indies; Cæsio is confined to the Indian Ocean and its gulfs; and Gerres spreads itself over all the tropical seas. The Family is of little importance to man; the Common Mendole (Mæna vulgaris, Cuv.) of the Mediterranean, is considered so utterly worthless, that its name in Venice is a proverb of vileness, and has passed into the vocabulary of insult. A West Indian species of Gerres is remarkable for the rapidity with which it decomposes, the flesh becoming soft almost immediately after it is dead. Another species of this genus, however (Gerres rhombeus, Cuv.) is esteemed one of the best fishes in Jamaica, where it goes by the name of Stone Basse. This little fish is reported by Mr. Couch to visit the coast of Cornwall, arriving there in considerable numbers, accompanying pieces of floating timber covered with Barnacles. Hence it is probable that these shelled Cirripedes form the favourite food of the Gerres, though M. Cuvier says that he has never found in its stomach anything but the remains of very minute fishes. The species of the genus Smaris, which we shall select to illustrate the Family, are sufficiently esteemed to be the subjects of fisheries of some importance, on the European coasts of the Mediterranean.

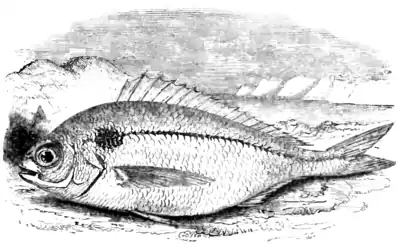

Genus Smaris (Cuv.).

The general form is that of a Herring, but rather more lengthened in proportion to the breadth. The mouth is very protrusile; the jaws are furnished with fine slender teeth, but the vomer is toothless. The fins are destitute of scales, except some on the sides of the ventrals; the scales between the ventrals are elongated.

The fishes are called Picarels by the French, but on the coasts and among the isles of Greece they retain their ancient name, slightly modified, marida being only a corruption of Σμαρὶς, the term by which these little fishes were designated in ancient times. They frequent the shallows of the shore, especially where the bottom is muddy and weedy; hiding among the marine vegetation, like birds among the bushes, and preying upon small fishes, and the feebler crustacea and mollusca. One species, the commonest of all (Smaris vulgaris, Cuv.), abounds so much at Iviça, one of the Balearic Isles, that according to M. de Laroche, it forms more than half of the whole produce of the fisheries of that island. It bears here the name of jarret. Rondelet tells us that after having been salted, the Picarel is exposed to the action of the air, to make a sort of garum, or sauce. It has been supposed that the appellation of Picarel, was derived from picoter, to prick or stimulate, alluding to the pungent taste of the sauce so prepared. But M. Duhamel denies the correctness of this; for, according to the observations of a correspondent of his, from Antibes, the Picarel is here confounded with a small species of the Herring genus, called there pyraie. He asserts that it is this fish, and not the true Picarel, which is made into sauce.

The most beautiful species of the genus is that called by the fishermen of Nice, the Kingfisher of the Sea (Smaris alcedo, Cuv.), in allusion to its brilliant tints. This lovely little fish does not commonly exceed seven inches in length. The upper parts are grey with golden reflections; the sides are silvery; the belly tinged with yellowish-green. The head and the gill-covers are marked with blue dashes; the sides are ornamented with four longitudinal lines of spots, of the most radiant ultramarine blue; and on the belly there are six similar rows of a paler tint. The dorsal, anal, and caudal fins are of a beautiful yellow, spotted with blue; the pectorals are reddish; the ventrals are pale blue, mottled with

reddish, and bordered with yellow. The Mediterranean coast of France is the locality frequented by this brilliant species, of whose distinctive natural history nothing seems to be recorded.

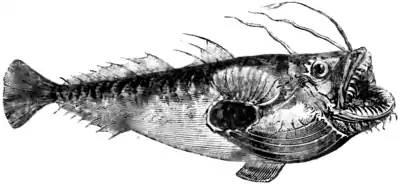

Family VIII. Chætodontidæ.

(Chætodons.)

We arrive now at a Family of Spinous-finned fishes, particularly interesting on account of the peculiarities of form and of colour that commonly distinguish them, but quite unknown to the cold waters of our northern clime. Cuvier assigned to the Family the appellation of Squamipennes, which is sufficiently expressive of one of their prominent characteristics; the soft, and frequently even the spinous parts of their dorsal and anal fins, being fleshy, and covered with scales, by which they are encrusted like the rest of the body; and thus their origin is not readily distinguished. Their form is generally exceedingly thin, but being greatly dilated in the vertical direction, and much shortened longitudinally, their appearance, at least in the typical genera, approaches to that of a piece of money, more or less nearly, that is, round and thin. The teeth are fine, long, and slender, resembling hairs collected in several close rows, like the bristles of a brush. The name Chætodon, by which Linnæus designated the whole Family, signifies bristle-tooth, and describes this peculiarity of dentition. The mouth is small, and usually projects in a prominent and pointed snout. The fins are usually much developed, particularly the dorsal and anal, the former of which sometimes terminates in one or more free filaments of great length and slenderness, as in the genera Heniochus and Zanclus, for example. In the genus Psettus, the body is so drawn out above and below, and the dorsal and anal fins are so pointed and hooked, that the fish when laid on its side, bears no slight resemblance to the figure of a bat with expanded wings. Platax has these fins still more enormously lengthened and pointed, as are, in this genus, the ventrals also.

The beauty of these fishes, which are generally of very small size, never fails to evoke the admiration of those who, with eyes opened to the wonderful works of God, visit the shores of the tropical seas. "In the Chætodons," observes an eloquent naturalist, "the seas of the torrid zone possess animals not less ornamented by the hand of Nature [rather by the hand of Nature's Lord], than the countries whose shores are bathed by these waters. If the hot countries of Africa and America have, among their feathered tribes, their souimangas, their humming-birds, their cotingas, and their tanagers, the intermediate seas support

myriads of the finny race still more brilliant, whose scales reflect the tints of metals and precious stones, heightened in effect by spots and bands of a more sombre hue, distributed with a symmetry and variety equally admirable. The genus Chætodon has many species in which Nature appears almost to have disported herself by clothing them in the most gaudy manner. Rose, purple, azure, and velvety black, are distributed along the surface of their bodies, in stripes, rings, and ocellated spots on a silver ground; nor are the beauties of these fishes lost to man, or confined to the depths of ocean. They are small, and usually remain near the shore, between the rocks, where there is but little water. Here they are incessantly sporting in the sun-beams, as if for the purpose of displaying the ornaments they have received from Nature."[10]

In almost all the members of this numerous Family, the muzzle projects into a prominent snout; and in some of the genera, as Zanclus, and more especially Chelmon, it is produced into a long narrow tube. In the latter genus, a very curious instinct and endowment attend this peculiarity of structure. In the year 1763, Dr. Schlosser presented to the Royal Society a specimen of the East Indian species, now known as Chelmon rostratus, with some information on its singular habits, which had been given him by Mr. Hommel, governor of the hospital at Batavia, in Java. The fish "frequents the shores and sides of the sea and rivers in search of food; when it spies a fly sitting on the plants that grow in shallow water, it swims on to [within] the distance of four, five, or six feet; and then, with a surprising dexterity, it ejects out of its tubular mouth, a single drop of water, which never fails striking the fly into the sea, when it soon becomes its prey.

"The relation of this uncommon action of this cunning fish, raised the Governor's curiosity; though it came well attested, yet he was determined, if possible, to be convinced of the truth by ocular demonstration. For that purpose he ordered a large wide tub to be filled with sea-water, then had some of these fish caught, and put into it, which was changed every other day. In a while they seemed reconciled to their confinement; then he determined to try the experiment.

"A slender stick, with a fly pinned on at its end, was placed in such a direction on the side of the vessel as the fish could strike it. It was with inexpressible delight that he daily saw these fish exercising their skill in shooting at the fly with an amazing velocity, and never missed their mark."[11]

As this beautiful little trait of instinctive skill has been often noticed, we have thought that our readers might like to have the very words in which it was originally communicated to the world, and have, therefore, cited the Memoir of Dr. Schlosser. It has since been witnessed by M. Reinwardt, who repeated the facts to M. Valenciennes. According to this naturalist, the Chinese inhabitants of Java are fond of keeping these little fishes in vessels of glass and porcelain for their amusement; frequently suspending an insect by a thread, or fastening it to a stick above the margins.