ORDER IV. GYRATORES.

(Circling Birds.)

While some naturalists, following Linnæus, have considered the great group of birds well known under the names of Pigeons and Doves, as constituting a Family of the extensive Passerine Order, and others, with the illustrious Cuvier, have placed them in that of the Gallinaceous or Poultry-like birds,—others, of equally high consideration, prefer to elevate them to the rank of an Order of themselves. Like the Passeres in general, the Pigeons associate in pairs at the season of courtship, the male and female working conjointly to form the nest, taking their turns in the wearying labours of incubation, and participating in the care of the young; the latter, also, are hatched blind and naked, are fed in the nest until they are fledged, and are sustained by the parents even some time after they have quitted it, having no power to feed themselves.

On the other hand, they differ from the Passeres in their mode of drinking, and of feeding their young, in the character of their plumage, in the singular tenderness of their courtship, and in the hollow and inward character of their voice.

With the Gallinaceous tribes they have also many points in common. In the peculiarities of their internal anatomy they are closely assimilated to these; their feet, though formed on the Passerine type, yet allow them to walk with ease and freedom; and many of the species habitually spend their time on the ground, perching very little; the gait and manners of some species are closely like those of the Poultry, and there is a sensible approximation to the latter in the tones of their peculiar voice. But, the differences are more important than the agreements of these groups: the Gallinaceous birds in general do not pair, but each male associates with many females; they lay many eggs each time they incubate, which is rarely more than once a year, at least in the temperate zones; while the Pigeons, as has been said, mate, and form permanent connubial attachments; the females lay only two eggs at each time, but incubate frequently during the year. In the Gallinaceous Order the posterior toe is jointed upon the tarsus higher up than the other toes, and touches the ground in walking only with the claw, or at most with the extreme joint, and remains perpendicular when the bird is on the perch. In the Pigeons, the hind toe is articulated at the bottom of the tarsus on the same level as the others, resting on the ground throughout its length, and embracing the branch in perching.

On the whole, then, we adhere to the opinion of those ornithologists who regard the Pigeons as an Order of birds, containing but a single Family.

Family I. Columbadæ.

(Pigeons.)

The Pigeons have the beak of moderate length, somewhat slender, swollen towards the tip, which is curved downwards: the base of the upper mandible is covered with a soft skin, inflated on each side, in which the nostrils are pierced. The wings vary in length, and in adaptation to powerful flight. The feet are comparatively short; the toes, divided to the base, are arranged three in front, and one behind; they have no spurs.

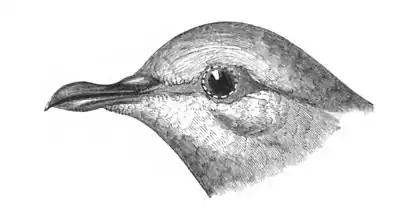

HEAD OF PIGEON.

"One part of the internal organization of the Pigeon is worthy of special notice. The crop, in the state which is adapted for ordinary digestion, is thin and membranous, and the internal surface is smooth; but by the time the young are about to be hatched, the whole, except that part which lies on the trachea [or wind-pipe] becomes thicker, and puts on a glandular appearance, having its internal surface very irregular. In this organ it is that the food is elaborated by the parents before it is conveyed to the young; for a milky fluid of a greyish colour is secreted and poured into the crop among the grain or seeds undergoing digestion, and a quality of food suited to the nestling is thus produced. The fluid coagulates with acids and forms curd; and the apparatus forms, among the birds, the nearest approach to the mammae of the Mammalia"[1]

The form of the Pigeons and their motions are graceful and elegant: the head is small in proportion, the body plump and rounded, the plumage full, compact, and smooth. The prevailing hues in the typical genus are various shades of blue and grey, merging into purple on the one hand, and into white on the other; in the Oceanic Pigeons green is the ordinary colour, varied with brilliant yellow. Metallic reflections of great beauty are common in the Family; not generally spread over the whole plumage, but confined to particular parts, and more especially the region of the neck. The expression of the countenance is peculiarly meek and gentle, and the eye large, liquid, and engaging. The voice, though frequently loud, has a soft and mournful character; it is known by the term cooing.

The geographical distribution of the Family is very extensive, the form occurring almost every where, except within the frigid zones. The species also are very numerous; and are most abundant in the south-eastern regions of Asia, and the great Oriental Archipelago.

Genus Columba. (Linn.)

In this, the typical genus, which contains the species common to Europe, the beak is of moderate strength, straight at the base, compressed at the sides, with the tip bent downward: the nostrils nearly linear, covered with a soft, swollen membrane; the tarsi short, partly feathered in front; the hind toe rather long; the wings powerful, rather pointed, the second quill longest; the tail nearly even at the extremity.

The species of this genus are very numerous, and widely spread over the globe: they commonly breed on tall trees, on the branches of which they construct rude and artless nests of twigs loosely put together, so as to form a slight platform, sometimes without the slightest concavity. Some, however, breed in the holes and on the ledges of rocks.

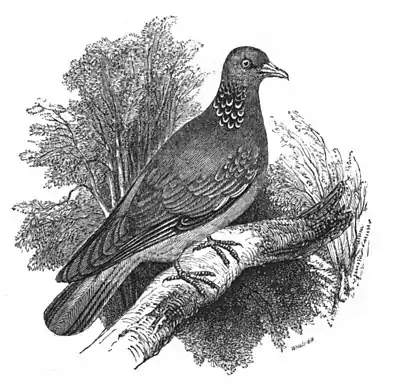

We select for illustration of the genus, one of the largest of its species, the common Ring-dove, or Wood-pigeon, of our own country (Columba palumbus, Linn.), called also, provincially, the Queest and the Cushat.

This fine bird is of a bluish-grey tint on the upper parts, which is darker on the back and wing coverts; the breast is purplish-red, becoming grey on the lower parts; the sides and front of the neck display rich metallic reflections of green and purple; some of the feathers of this part are tipped with white, forming an imperfect ring of white, partly encircling the neck, whence its most common name.

The Ring-dove is a constant resident in the British Islands, as it is in all the temperate parts of Europe; it affects well wooded districts, being shy and recluse in its habits. Its mournful cooing is heard in such situations almost incessantly during the spring months, though it is rarely seen, except when, the rushing of its powerful

WOOD-PIGEON.

The food of the Ring-dove consists of grain of all kinds, pulse, especially peas, both ripe and green, and young leaves and shoots of clover; in autumn, acorns and beech-mast form an abundant supply, and when these are exhausted, the bird does not disdain winter-berries, and even the leaves of turnips and other green-crops, and the roots of various grasses and weeds. During the breeding season they unite in pairs, but at other times they associate in large flocks, which, however they wander during the day, resort at night to a common resting-place, by watching at which they are shot with ease, as the straggling parties successively arrive for the night's repose. Their flesh is in high esteem for its tenderness, juiciness, and flavour.

The nest, consisting only of a few sticks loosely laid across, is yet admirably calculated for the purpose of concealment. "How often," remarks Mr. Jesse, "have I observed the strong, rapid flight of a Wood-pigeon from a tree, and heard the noise produced by his wings, and yet have been unable to discover its nest! This has been owing to the deposits of dead leaves and small branches, which have been accumulated in various parts of the tree, and which have exactly the same appearance as the nest itself."[3]